Latin Americans generally embrace democracy as their preferred form of government. In most of the countries surveyed, majorities or pluralities also say they would prefer a government that refrains from promoting religious values and beliefs. But Latin Americans are more divided on the extent to which religious leaders should influence politics.

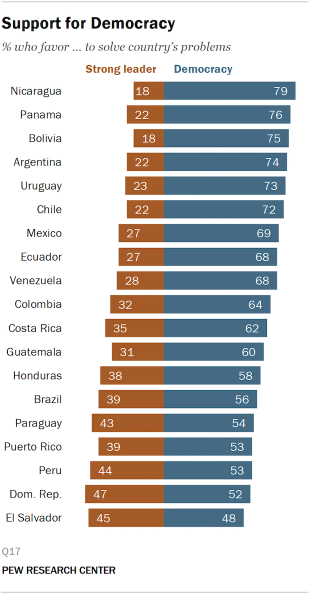

Democracy Favored Over Strong Leader

In most countries surveyed, solid majorities say they would prefer “a democratic form of government” over “a leader with a strong hand” to solve their country’s problems. Yet support for democracy is not equally strong across Latin America. In El Salvador, for example, the public is closely divided between those who favor democracy (48%) and those who say that a strong leader is preferable (45%). At the other end of the spectrum, roughly eight-in-ten people in nearby Nicaragua (79%) favor democracy, while just 18% prefer a leader with a strong hand.

Although the survey shows substantial variations among countries, within each country the major religious groups – Catholics, Protestants and the religiously unaffiliated – tend to express similar views on this question. (For details, see survey topline.) Younger and older adults, as well as men and women, are about equally likely to prefer democracy over a strong leader.

Latin Americans with at least a secondary school education are more likely than those with less than a secondary education to prefer democracy, although in most countries, majorities of both groups favor democracy over a strong leader.

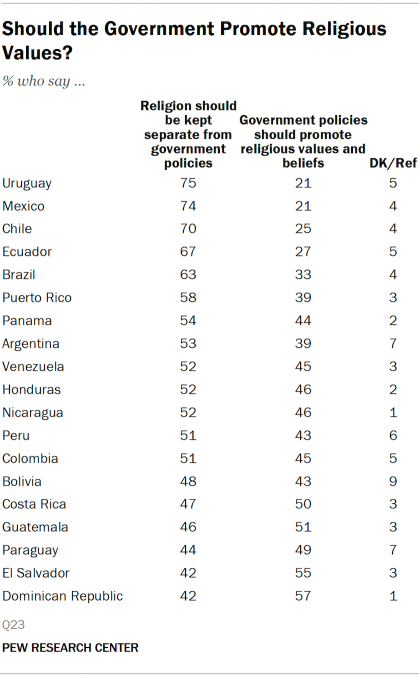

Role of Religion in Politics

In most countries across the region, more Latin Americans say church and state should be “kept separate” than say the government “should promote religious values and beliefs.”

However, in a handful of countries, including Costa Rica, Guatemala and Paraguay, the public is closely divided on this issue. And in the Dominican Republic and El Salvador, the public leans toward the position that government should promote religious values and beliefs rather than separating church and state.

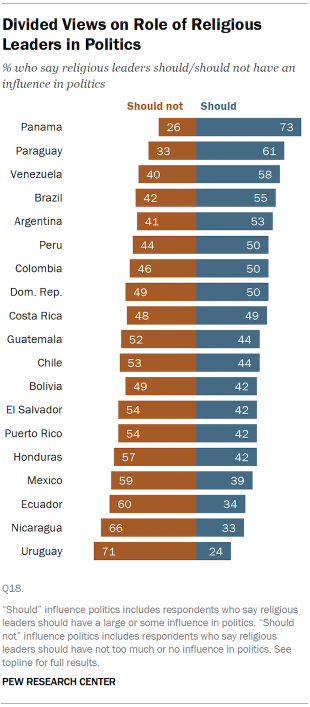

While most Latin Americans prefer a separation between church and state, opinion is closely divided on the role religious leaders should play in politics. In five of the countries polled – Panama, Paraguay, Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina – majorities or pluralities say that religious leaders should have either “some influence” or a “large influence” in politics. But in nine countries and Puerto Rico, the preponderance of public opinion leans in the opposite direction, with more respondents saying that religious leaders should have either “not too much influence” or “no influence at all” on political matters. (In four countries – Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Peru – publics are split.)

Generally speaking, Catholics and Protestants across the region share similar views on the broad question of religion in politics. In Honduras, for example, roughly half of adults (52%) say religion should be kept separate from government, including 55% of Catholics as well as 49% of Protestants. Similarly, roughly four-in-ten Honduran Catholics (43%) as well as Honduran Protestants (40%) say that religious leaders should have at least some influence in politics. (For details, see survey topline.)

On balance, somewhat fewer religiously unaffiliated people support government promotion of religion and religious leaders having an influence in politics. But in about half of the countries where sample sizes allow analysis, including Brazil, the Dominican Republic and Honduras, the religiously unaffiliated are about as likely as Catholics and Protestants to say that government policies should promote religious values and that religious leaders should have at least some influence in politics. (For details, see survey topline.)

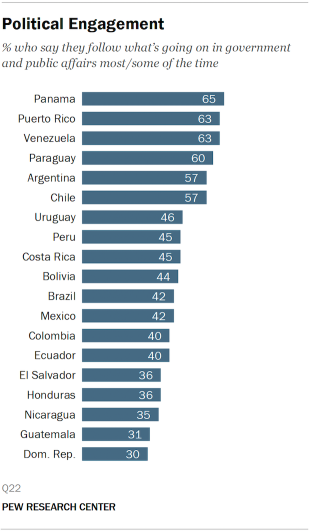

Political Engagement

Interest in politics varies substantially across the Latin American countries surveyed. Majorities say they often or sometimes follow what is going on in government and public affairs in Panama (65%), Puerto Rico (63%), Venezuela (63%), Paraguay (60%), Argentina (57%) and Chile (57%). In the other countries polled, less than half of the public closely follows political news, with interest lowest in Guatemala (31%) and the Dominican Republic (30%).

Overall, men and adults with at least a secondary school education are more likely to follow news about public affairs than are women and those with less education. Latin Americans ages 35 and older also are more likely than younger adults to follow public affairs.

With regard to religion, Catholics, Protestants and the religiously unaffiliated are about equally likely to say that they at least sometimes follow political news and events. Only in Argentina and Bolivia are Catholics more likely than Protestants to say they follow public affairs.