Christians remain by far the largest religious group in the United States, but the Christian share of the population has declined markedly. In the past seven years, the percentage of adults who describe themselves as Christians has dropped from 78.4% to 70.6%.

Once an overwhelmingly Protestant nation, the U.S. no longer has a Protestant majority. In 2007, when the Pew Research Center conducted its first Religious Landscape Study, more than half of adults (51.3%) identified as Protestants. Today, by comparison, 46.5% of adults describe themselves as Protestants.

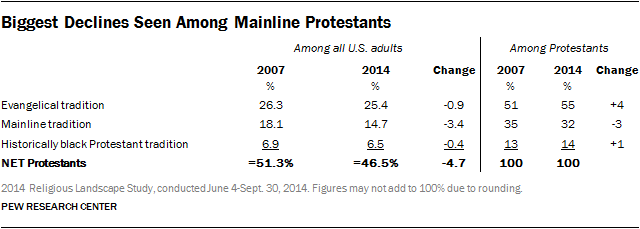

While there have been declines across a variety of Protestant denominations, the most pronounced changes have occurred in churches in the mainline Protestant tradition, such as the United Methodist Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The share of adults belonging to mainline churches dropped from 18.1% in 2007 to 14.7% in 2014. This is similar to the drop seen among U.S. Catholics, whose share of the population declined from 23.9% to 20.8% during the same seven-year period.

In contrast with mainline Protestantism, there has been less change in recent years in the proportion of the population that belongs to churches in the evangelical or historically black Protestant traditions. Evangelicals now make up a clear majority (55%) of all U.S. Protestants. In 2007, 51% of U.S. Protestants identified with evangelical churches.

While the overall Christian share of the population has dropped in recent years, the number of Americans who do not identify with any religion has soared. Nearly 23% of all U.S. adults now say they are religiously unaffiliated, up from about 16% in 2007. While most of the unaffiliated describe themselves as having “no particular religion,” a growing share say they are atheists or agnostics.

This chapter takes a close look at the current religious composition of the United States and how it has changed since 2007. A full-page table (PDF) summarizes the religious affiliation of U.S. adults in a way that captures small groups that make up less than 1% of the population.

The chapter also explains how Protestant respondents were sorted into the three distinct Protestant traditions – the evangelical Protestant tradition, the mainline Protestant tradition and the historically black Protestant tradition – and it documents which Protestant denominations are shrinking, and which are growing.

Finally, the chapter examines the growth of non-Christian religions in the U.S. and takes a closer look at the composition of the religiously unaffiliated population.

Measuring and Categorizing Protestantism

American Protestantism is diverse, encompassing more than a dozen major denominational families – such as Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans and Pentecostals – all with unique beliefs, practices and histories. These denominational families, in turn, are made up of a host of different denominations, such as the Southern Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Churches USA and the National Baptist Convention.

Denominations: The term “denomination” refers to a set of congregations that belong to a single administrative structure characterized by particular doctrines and practices. Examples of denominations include the Southern Baptist Convention, the American Baptist Churches USA and the National Baptist Convention.

Families: A denominational family is a set of religious denominations and related congregations with a common historical origin. Examples of families include Baptists, Methodists and Lutherans. Most denominational families consist of denominations that are associated with more than one of the three Protestant traditions. The Baptist family, for instance, consists of some denominations that fall into the evangelical tradition, others that belong to the mainline tradition and still others that are part of the historically black Protestant tradition.

Traditions: A religious tradition is a set of denominations and congregations with similar beliefs, practices and origins. In this report, Protestant denominations are grouped into three traditions: the evangelical tradition, the mainline tradition and the historically black Protestant tradition.

Because of this great diversity, American Protestantism is best understood not as a single religious tradition but rather as three distinct traditions – the evangelical Protestant tradition, the mainline Protestant tradition and the historically black Protestant tradition. Each of these traditions is made up of numerous denominations and congregations that share similar beliefs, practices and histories.

For instance, churches within the evangelical tradition tend to share religious beliefs (including the conviction that personal acceptance of Jesus Christ is the only way to salvation), practices (like an emphasis on bringing other people to the faith) and origins (including separatist movements against established religious institutions). Churches in the mainline tradition, by contrast, share other doctrines (such as a less exclusionary view of salvation), practices (such as a strong emphasis on social reform) and origins. Churches in the historically black Protestant tradition have been shaped uniquely by the experiences of slavery and segregation, which put their religious beliefs and practices in a special context.

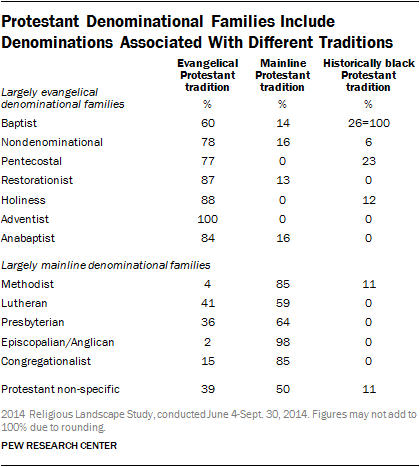

As much as possible, Protestant respondents were categorized into one of the three Protestant traditions based not on their denominational family, but rather on the specific denomination with which they identify. Most Protestant denominational families include denominations that are associated with different Protestant traditions. For example, some Baptist denominations (like the Southern Baptist Convention) are part of the evangelical tradition; others (such as the American Baptist Churches USA) are part of the mainline tradition; and still others (such as the National Baptist Convention) are part of the historically black Protestant tradition.

Overall, 60% of Baptists in the survey identify with denominations in the evangelical tradition; 14% associate with denominations in the mainline Protestant tradition, and 26% identify with denominations that are part of the historically black Protestant tradition. (While the Baptist family of denominations includes churches in all three Protestant traditions, this is not the case for all denominational families, some of which have members in just one or two of the Protestant traditions.)

Despite the detailed denominational measures used in the Religious Landscape Study, many respondents (more than a quarter of all Protestants) were either unable or unwilling to describe their specific denominational affiliation. For instance, some respondents describe themselves as “just a Baptist” or “just a Methodist.” Respondents with this type of vague denominational affiliation were sorted into one of the three Protestant traditions in two ways.13

First, blacks who gave vague denominational affiliations (e.g., “just a Methodist”) but who said they belong to a Protestant family with a sizable number of historically black churches (including the Baptist, Methodist, nondenominational, Pentecostal and Holiness families) were coded as members of the historically black Protestant tradition. Black respondents in denominational families without a sizable number of churches in the historically black Protestant tradition were coded as members of the evangelical or mainline Protestant traditions depending on their response to a separate question asking whether they would identify as a born-again or evangelical Christian.

Second, non-black respondents who gave vague denominational identities and who described themselves as born-again or evangelical Christians were coded as members of the evangelical tradition; otherwise, they were coded as members of the mainline tradition.14

Overall, 38% of Protestants offered a vague denominational identity and thus were classified on the basis of their race and/or their answer to the question about whether they identify as a born-again or evangelical Christian. This includes 36% of those in the evangelical tradition, 35% of those in the mainline tradition and 53% of those in the historically black Protestant tradition.

The Shifting Composition of American Protestantism

Recent years have brought a dramatic decline in the share of Americans who identify with mainline Protestant denominations. Today, just 15% of all U.S. adults identify with mainline Protestant churches, down from 18% in 2007. By comparison, evangelical Protestantism and the historically black Protestant tradition have been more stable. Today, 25% of U.S. adults identify with evangelical denominations, down less than one percentage point since 2007. And roughly 7% of American adults identify with the historically black Protestant tradition, little changed since 2007.

The mainline tradition’s share of the Protestant population has declined along with its share of the overall population. Today, 32% of Protestants identify with denominations in the mainline tradition, down from 35% in 2007. Evangelicals now constitute a clear majority of all Protestants in the U.S., with their share of the Protestant population having risen from 51% in 2007 to 55% in 2014.

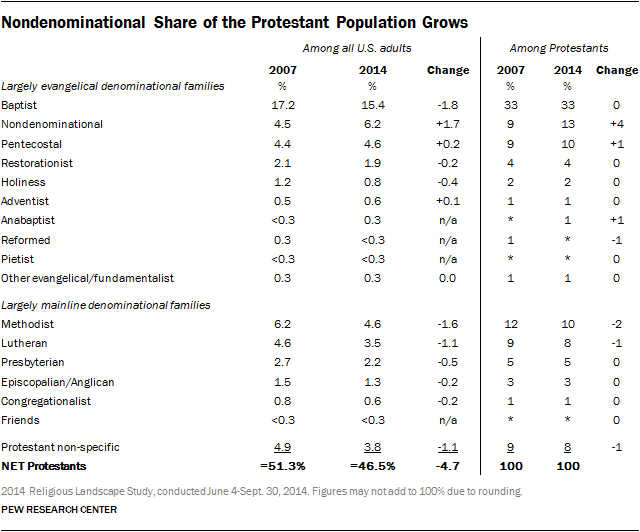

Many Protestant denominational families have seen their share of the U.S. population fall since 2007. Baptists now account for approximately 15% of the adult population, down from 17% in 2007. Methodists and Lutherans also have declined by more than a full percentage point in recent years. The family that shows the most significant growth is the nondenominational family; today, 6.2% of all adults (and 13% of Protestants) identify with nondenominational churches, up from 4.5% of all adults (and 9% of all Protestants) in 2007.

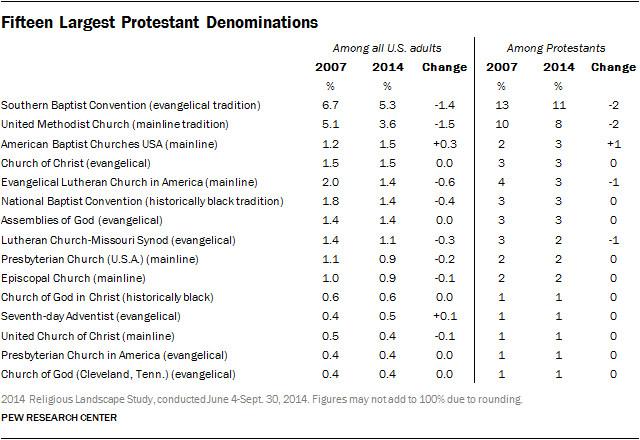

The Southern Baptist Convention (an evangelical denomination) and the United Methodist Church (a mainline denomination) continue to be the two largest Protestant denominations in the U.S.; 11% of Protestants identify with the Southern Baptist Convention and 8% identify with the United Methodist Church. Both denominations, however, have experienced declines in their relative share of the population. In the 2014 Religious Landscape Study, 5.3% of all U.S. adults identify with the Southern Baptist Convention (down from 6.7% in 2007) and 3.6% identify with the United Methodist Church (down from 5.1% in 2007).

Growth of Non-Christian Faiths

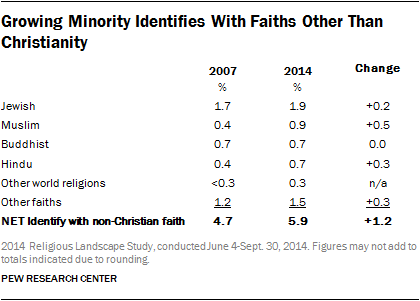

The 2014 Religious Landscape Study finds that 5.9% of U.S. adults identify with faiths other than Christianity, up slightly, but significantly, from 4.7% in 2007. The largest of these faiths is Judaism, with 1.9% of respondents identifying themselves as Jewish when asked about their religion. Among Jews surveyed, 44% identify with Reform Judaism, 22% with Conservative Judaism, 14% with Orthodox Judaism, 5% with other Jewish movements and 16% with no particular Jewish denomination. These findings are broadly similar to results from the Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey of Jewish Americans.15

Muslims (0.9%), Buddhists (0.7%) and Hindus (0.7%) each make up slightly less than 1% of respondents in the 2014 Religious Landscape Study. The Muslim and Hindu shares of the population have risen significantly since 2007. And it is possible, even despite this growth, that the Religious Landscape Study may underestimate the size of these groups. The study was conducted in English and Spanish, which means that groups with above-average numbers of people who do not speak English or Spanish (such as immigrants from Asia, Africa and other parts of the world) may be underrepresented. For instance, an analysis of the Pew Research Center’s 2012 survey of Asian Americans (conducted in English, Cantonese, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Tagalog and Vietnamese) estimated that Buddhists account for between 1.0% and 1.3% of the U.S. adult population, and that Hindus account for between 0.5% and 0.8% of the population. The Pew Research Center’s 2007 and 2011 surveys of Muslim Americans (conducted in English, Arabic, Farsi and Urdu) estimated that Muslims accounted for 0.6% of the adult population in 2007 and 0.8% in 2011.

The 2014 Religious Landscape Study finds that 0.3% of American adults identify with a wide variety of other world religions, including Sikhs, Baha’is, Taoists, Jains, Rastafarians, Zoroastrians, Confucians and Druze. An additional 1.5% identify with other faiths, including Unitarians, those who identify with Native American religions, Pagans, Wiccans, New Agers, deists, Scientologists, pantheists, polytheists, Satanists and Druids, to name just a few.

Atheists and Agnostics Make Up a Growing Share of the Unaffiliated

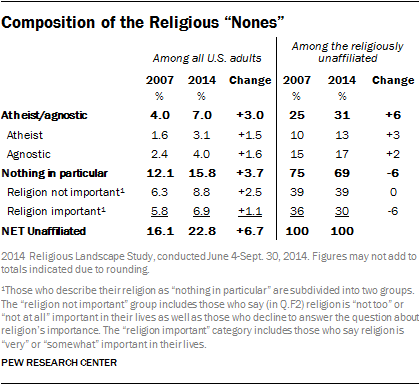

The religiously unaffiliated population – including all of its constituent subgroups – has grown rapidly as a share of the overall U.S. population. The share of self-identified atheists has nearly doubled in size since 2007, from 1.6% to 3.1%. Agnostics have grown from 2.4% to 4.0%. And those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” have swelled from 12.1% to 15.8% of the adult population since 2007. Overall, the religious “nones” have grown from 16.1% to 22.8% of the population in the past seven years.

As the unaffiliated have grown, the internal composition of the religious “nones” has changed. Most unaffiliated people continue to describe themselves as having no particular religion (rather than as being atheists or agnostics), but the “nones” appear to be growing more secular. Atheists and agnostics now account for 31% of all religious “nones,” up from 25% in 2007.

Meanwhile, the share of the “nones” describing their religion as “nothing in particular” has declined from 75% in 2007 to 69% in 2014. And this decline is especially notable among those who say religion is “very” or “somewhat” important in their lives despite eschewing any identification with a particular religion. Those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” and who also say that religion is important in their lives now account for 30% of all religious “nones,” down from 36% in 2007. Those who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” and furthermore state that religion is unimportant in their lives account for 39% of all religious “nones,” the same share as 2007.

A Note on How the Study Defines Evangelicals

How many Americans are evangelical Christians? The answer depends on how evangelicalism is being defined.

There are a number of ways this can be done. The approach taken in the 2014 Religious Landscape Study, for example, focuses only on Protestants. It looks at the denominations and congregations with which Protestants identify, and determines whether these denominations and congregations are part of the evangelical Protestant tradition, mainline Protestant tradition or historically black Protestant tradition. Those who belong to denominations and churches that are part of the evangelical Protestant tradition (such as the Southern Baptist Convention, the Assemblies of God and many nondenominational churches) are categorized as evangelical Protestants in the study; those who belong to denominations or churches in the other two Protestant traditions are not. Using this approach, the study finds that 25.4% of U.S. adults are evangelical Protestants, down from 26.3% in 2007, when the first Religious Landscape Study was conducted.

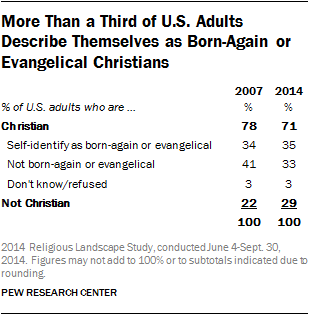

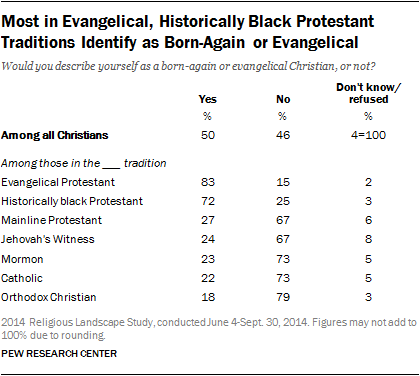

Another way to identify evangelicals is to ask people whether they consider themselves evangelical or born-again Christians. The Religious Landscape Study includes a question asking Christians: “Would you describe yourself as a born-again or evangelical Christian, or not?” In response to this question, half of Christians (35% of all U.S. adults) say yes, they do consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians. The share of self-described born-again or evangelical Christians is very similar to what it was in 2007, even though the overall Christian share of the population has declined.

Not surprisingly, most members of the evangelical Protestant tradition (83%) see themselves as born-again or evangelical Christians, as do most members of the historically black Protestant tradition (72%) and a sizable minority of people in the mainline Protestant tradition (27%). Many Christians who do not identify with Protestantism also consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians, including 22% of Catholics, 18% of Orthodox Christians, 23% of Mormons and 24% of Jehovah’s Witnesses.

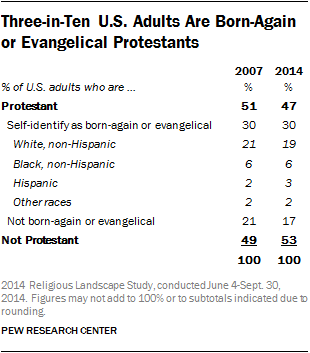

When Catholics, Mormons and other non-Protestants are excluded, the study finds that three-in-ten U.S. adults are self-described born-again or evangelical Protestants. Although the percentage of Americans who identify as Protestants has declined in recent years (from 51% in 2007 to 47% today), the share of born-again or evangelical Protestants has remained the same.

White born-again or evangelical Protestants – a group closely watched by political observers – now account for 19% of the adult population, down slightly from 21% in 2007. Over that period of time, the white share of respondents fell from 71% in the 2007 Religious Landscape Study to 66% in 2014. Another way to define evangelical Protestants is to identify a set of religious beliefs or practices that are central to evangelicalism, and then assess how many people profess those beliefs or engage in those practices. When measured this way, the size of the evangelical population depends on the particular beliefs and practices that are used to define the category. While this type of analysis is beyond the scope of the Religious Landscape Study, a forthcoming report will examine the beliefs and practices of major religious groups and their views on social and political issues.