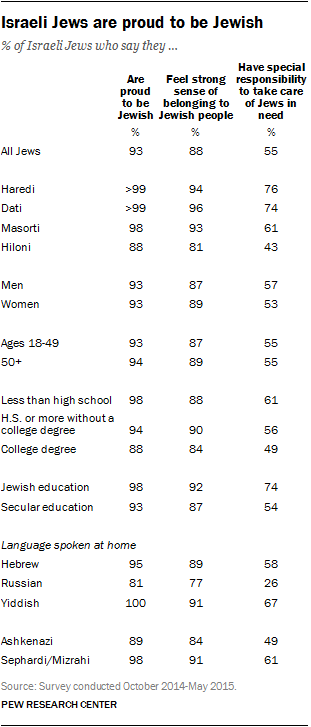

Overwhelmingly, Jews in Israel feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people and are proud to be Jewish. Fully 93% of Jews say they are proud of their Jewish identity and 88% say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people.

Even across the religious-secular divide that characterizes many aspects of Israeli Jewish society, majorities of Israeli Jews feel pride and a sense of belonging with the Jewish people. Nearly all Haredim interviewed in this survey say they are proud to be Jewish, as do 88% of Hilonim. Similarly, 94% of Haredim say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, as do 81% of Hilonim.

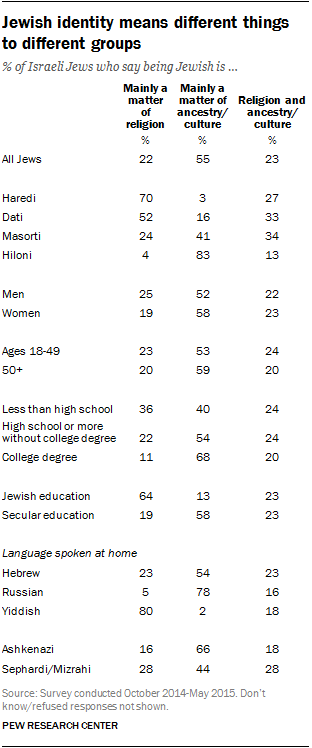

But Jews in Israel differ considerably from one another in how they understand their Jewish identity. A majority of Haredim (70%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of religion, while just 3% say being Jewish is mostly a matter of culture or ancestry. Hilonim have a very different concept of Jewish identity: 83% say being Jewish is mainly about ancestry or culture, while just 4% say their Jewish identity is mainly about religion.

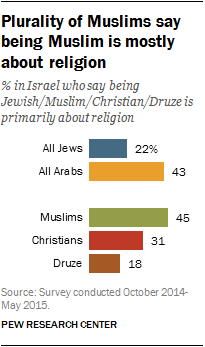

Overall, 22% of Jews say being Jewish is primarily about religion, while more than half (55%) say being Jewish is essentially about ancestry and/or culture. By comparison, about twice as many Muslims in Israel say being a Muslim is mainly about religion (45%). But the differing perspectives about identity are not unique to Jews; while Muslims are more likely than Jews to say their identity is primarily a matter of religion, about three-in-ten Muslims (29%) say being Muslim is primarily a matter of ancestry or culture. Similarly, about a third of Israeli Christians (34%) and Druze (33%) say their Christian/Druze identity is mainly about ancestry/culture.

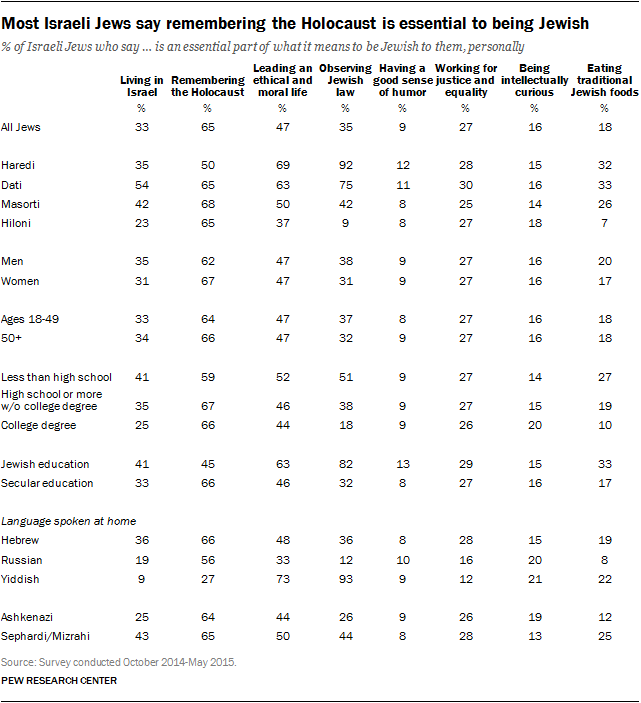

The survey asked Israeli Jews what elements are essential to their Jewish identity – both from a list of eight possible responses and in their own words. Most Israeli Jews say remembering the Holocaust is essential to what being Jewish means to them, personally. And when asked to explain the essential elements of their Jewish identity in their own words, 53% of Israeli Jews say providing a Jewish education to children or sharing Jewish traditions with children is essential to their Jewish identity.

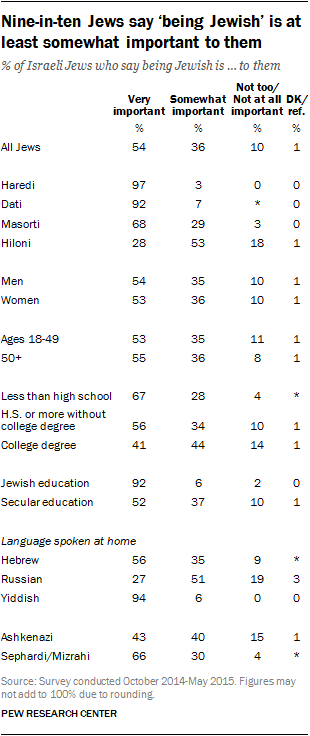

Pluralities of Jews say ‘being Jewish’ is very important to them

Overall, just over half of Israeli Jews (54%) say being Jewish is “very important” to them. Roughly a third (36%) say being Jewish is “somewhat” important, and 10% say being Jewish is “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives.

The share of Jews who say being Jewish is very important to them is considerably higher than the share of Jews who say religion is very important in their lives (54% vs. 30%). (For more on this latter question, see Chapter 4.)

There are striking differences in how Jews belonging to different religious subgroups see the importance of being Jewish in their lives. Hilonim stand out from other groups in the relative lack of importance they place on being Jewish. Only about a quarter of Hiloni adults say being Jewish is very important to them (28%), while most (53%) say it is somewhat important and 18% say it is not too or not at all important.

At the other end of the spectrum, virtually all Haredim (97%) say being Jewish is very important to them.

Datiim resemble Haredim on this issue; 92% of Dati adults say being Jewish is very important in their lives. Roughly two-thirds of Masortim (68%) say being Jewish is very important in their lives, while about three-in-ten (29%) say it is somewhat important.

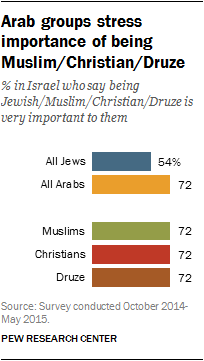

Israeli Arab groups are more likely to say they greatly value their Muslim/Christian/Druze identity (72% each) than their Jewish countrymen are to say “being Jewish” is very important to them (54%).

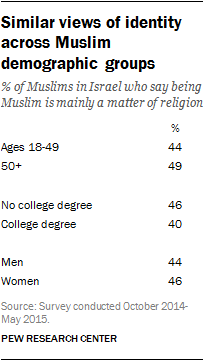

Among Muslims, as among Israeli Jews, there are no significant differences by age or gender on the importance of religious identity. And there are no statistically significant differences in the views of Muslims with different levels of educational attainment.

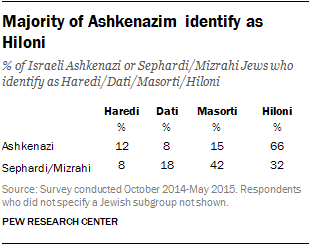

Israeli Jews are nearly evenly split between two Jewish ethnic identity groups – the Ashkenazim (45%) and the Sephardim or Mizrahim (48%). These two ethnic groups retain some distinct religious practices and cultural traditions associated with their ancestral roots. The chief rabbinate in Israel consists of two rabbis – one who is Ashkenazi and the other Sephardi.

The Ashkenazim (from the Hebrew term for Germany, Ashkenaz) trace their roots mainly to central and eastern Europe. (Indeed, a quarter of Israeli Ashkenazim say they speak primarily Russian at home.) Sephardim and Mizhrahim vary widely in their ancestral origin – from Spain’s Iberian Peninsula to the Middle East and Central Asia. Mizrahi (from Mizrah, meaning eastern in Hebrew) often is used interchangeably with Sephardi (or Sfaradit, meaning Spanish in Hebrew). Sephardim and Mizrahim have similar religious traditions and practices, distinct from those of the Ashkenazim. Sephardim typically trace their roots to ancestors who lived in Spain until they were expelled during the Spanish Inquisition. The Sephardim then migrated eastward and lived largely among the Mizrahim in the Middle East and North Africa.

Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews are, on average, more religiously observant than their Ashkenazi counterparts. Fully two-thirds of Ashkenazim identify as secular (Hiloni) Jews, compared with about three-in-ten of Sephardim/Mizrahim (32%). A plurality of Sephardim/Mizrahim (42%) identify as Masortim.

Over the course of Israel’s modern history, the Sephardi/Mizrahi community has experienced problems with discrimination and marginalization.16 This survey finds, however, that a majority of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews say there is not currently a lot of discrimination against Mizrahim in Israeli society (32% say there is a lot, 64% say there is not). However, it should be noted that Sephardim/Mizrahim are significantly more likely than Ashkenazim to say that Mizrahim face a lot of discrimination (32% vs. 9%).

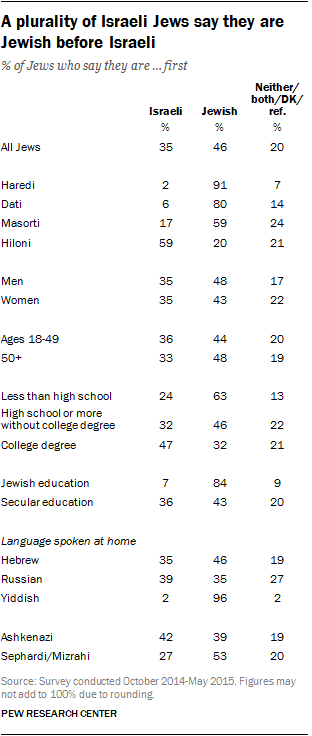

Overall, the survey finds Ashkenazim in Israel are more likely than Sephardim/Mizrahim to give priority to their Israeli identity over their Jewish identity. Fully 42% of Ashkenazim say they are Israeli first and Jewish second, compared with 27% of Sephardim/Mizrahim who say this. While Ashkenazim are closely divided among those who say they are Israeli first and those who say they are Jewish first, among Sephardim/Mizrahim, the prevailing view is that they are Jewish first (53%).

More say they are Jewish first, then Israeli

When asked whether they would describe themselves as Jewish first or Israeli first, a plurality of Israeli Jews (46%) say they are Jewish first. Roughly a third (35%) say they are Israeli first, while 20% do not give a clear answer either way.17

Hilonim stand out from other Jewish subgroups on this question. A majority of Hilonim (59%) say they are Israeli first, while among other groups, fewer than one-in-four describe themselves as Israeli before Jewish. Among Haredim, roughly nine-in-ten (91%) say they are Jewish first, while only 2% say they are Israeli first.

Non-Jews in Israel were not asked whether they identify more strongly with their religious identity or their Israeli identity.

Israeli Jews say being Jewish is primarily about ancestry or culture

Most Jews in Israel (55%) say being Jewish, to them, is mostly about ancestry or culture. Roughly one-in-five (22%) say being Jewish is mainly about religion, while roughly the same proportion (23%) say being Jewish is about a combination of religion and ancestry/culture.

But there are wide differences in how Israeli Jews belonging to different religious subgroups understand this aspect of their Jewish identity.

A majority of Haredim (70%) say being Jewish is mainly about religion, while 3% say their Jewish identity is mainly about their ancestry or culture. Among Hilonim, by comparison, just 4% say their personal Jewish identity is mainly about religion, while an overwhelming majority (83%) say being Jewish is mainly about ancestry or culture.

Among Datiim, roughly half (52%) say their Jewish identity is mainly about religion, while 16% name ancestry or culture. Meanwhile, roughly four-in-ten Masortim (41%) say their Jewish identity is primarily about ancestry or culture, while about a quarter (24%) say being Jewish is mostly about religion.

About three-in-ten Datiim, Masortim and Haredim see their Jewish identity as tied up in religion as well as ancestry and/or culture.

Arabs in Israel have multiple potential identities – including Arab, Palestinian and Israeli – in addition to their religious identities. When asked about the essence of Muslim identity, a plurality of Muslims in Israel (45%) say being Muslim is primarily a matter of religion to them, personally. But there are some divisions among Muslims about the essence of their identity. Fully 30% of Muslims say being a Muslim is mainly about ancestry or culture, and about one-in-five say Muslim identity is tied up in religion and ancestry/culture.

Among Muslims, there are no significant differences in views of Muslim identity between younger and older respondents, men and women and those who are college-educated versus those with less education.

The nature of Christian identity varies among Christians as well. Christians in Israel are about evenly divided among those who say their identity is mainly a matter of religion (31%), those who say being Christian is mainly about ancestry and/or culture (34%) and those who say their identity is characterized by a combination of religion and ancestry/culture (34%).

Among Druze, 18% say being Druze is primarily a matter of religion. A third of Druze say that to them, personally, being Druze is essentially about ancestry or culture, while nearly half of Druze adults (47%) say their identity is tied up in a combination of these elements.

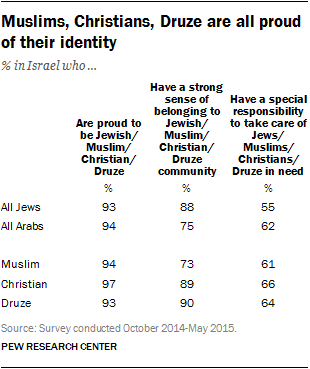

Jews feel pride, connectedness and responsibility in Jewish community

Across different age groups and educational, ethnic and religious backgrounds, the vast majority of Jews in Israel agree that they are proud to be Jewish and have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people. And more than half of Jews in Israel (55%) say they have a special responsibility to take care of Jews in need around the world.

Fully 93% of Israeli Jews say they are proud to be Jewish. Haredi and Dati Jews almost universally say this (>99%), as do virtually all Masorti Jews (98%). Somewhat fewer Hilonim say this – however, 88% still say they are proud of this aspect of their identity.

Similarly, while Russian-speaking Jews are somewhat less likely than Hebrew- or Yiddish- speaking Jews to express pride in being Jewish, majorities among all three groups say they are proud to be Jewish.

Overwhelmingly, Israeli Jews have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people. Fully 88% of Jews in Israel – including majorities in all four major religious subgroups – say they feel closely connected to the Jewish people.

Compared with pride and connectedness, fewer Israeli Jews (55%) say they feel a special responsibility to take care of Jews in need around the world. On this question, there are larger gaps between religious and secular Jews. Roughly three-quarters of Haredim (76%) and Datiim (74%) say they have a special responsibility to take care of Jews in need, but fewer than half of Hilonim (43%) feel this responsibility.

In Israel, Muslims, Christians and Druze are about as likely as Jews to say they are proud of their identity. About nine-in-ten Arabs (94%) say their identity as a Muslim, Christian or Druze is a matter of pride for them. But Arabs are slightly more likely than Jews to say they have a special responsibility to help fellow members of their religious group who are in need around the world.

Overall, Muslims are somewhat less likely to say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Muslim community than Jews are to say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people (73% vs. 88%).18 Christians and Druze, meanwhile, are about as likely as Jews to say they feel a sense of belonging to their broadly defined group.

Little consensus among Israeli Jews about what is essential to Jewish identity

The survey asked Jews in Israel whether each of eight attributes and behaviors is essential, important but not essential, or not important to what being Jewish means to them, personally.

Overall, a majority of Israeli Jews (65%) say remembering the Holocaust is essential to their Jewish identity. Nearly half (47%) say living an ethical or moral life is essential to being Jewish, while roughly one-third say observing halakha (35%), living in Israel (33%) or working for justice and equality in society (27%) are essential to being Jewish. Smaller shares of Jews say eating traditional Jewish foods (18%), being intellectually curious (16%) or having a good sense of humor (9%) are essential aspects of their Jewish identity.

There are some important differences in the views of Jews belonging to different religious subgroups on the essential aspects of Jewish identity. Religiously observant Jews are more likely than less religious Jews to say living a moral and ethical life is essential to being Jewish. For example, a majority of Haredim (69%) say ethical living is essential to being Jewish, compared with 37% of Hilonim.

There is an even bigger gap when it comes to whether observing Jewish law, or halakha, is central to Jewish identity. An overwhelming proportion of Haredim (92%) and three-quarters of Datiim (75%) say observing halakha is essential to being Jewish, compared with fewer than half of Masortim (42%) and just 9% of Hilonim.

Perhaps as a reflection of their emphasis on religious rather than cultural, historical or ancestral aspects of being Jewish, Haredim are less likely than other groups to say that remembering the Holocaust is an essential part of what being Jewish means to them. Half of Haredim in Israel (50%) say this, compared with roughly two-thirds of Datiim, Masortim and Hilonim. Even among Yiddish-speaking Jews – virtually all of whom are Haredim whose roots are generally in Europe – just 27% say that remembering the Holocaust is essential to their Jewish identity.

“Living in Israel” was among the possible “essentials” of Jewish identity mentioned in the survey. About a quarter of Hilonim (23%) and a third of Haredim (35%) say it is essential to what being Jewish means to them, compared with about four-in-ten among Masortim (42%) and about half of Datiim (54%).

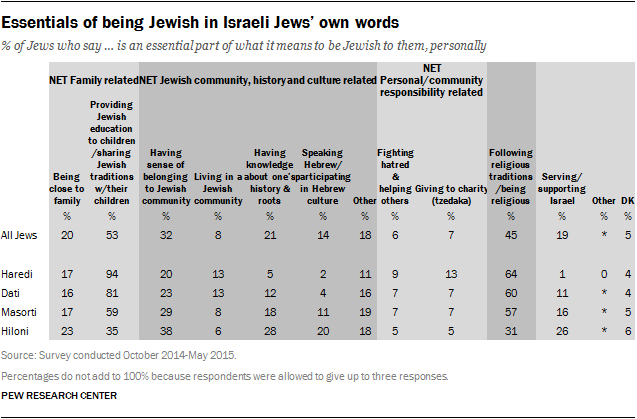

The survey also asked Jews whether there are any components of Jewish identity that were not previously mentioned, yet that are essential to them. Respondents were asked to explain, in their own words, up to three additional elements of their Jewish identity. The answers show that Jews in Israel tend to view community, history and traditions as central to their Jewish identity, and many emphasize the need to pass on these traditions to future generations.

Specifically, a majority of Israeli Jews (73%) describe strong family bonds as central to their Jewish identity. This includes roughly half (53%) who say passing on Jewish traditions to their children is essential to what being Jewish means to them. In addition, 32% of Jews say having a sense of belonging to the Jewish community is essential to their Jewish identity, and roughly one-in-five (21%) mention having knowledge about one’s history and roots.

More than four-in-ten Jews (45%) also say following religious traditions or being religious is essential. Fewer (19%) say the same about serving or supporting Israel, with Haredim especially unlikely to say this (1%).

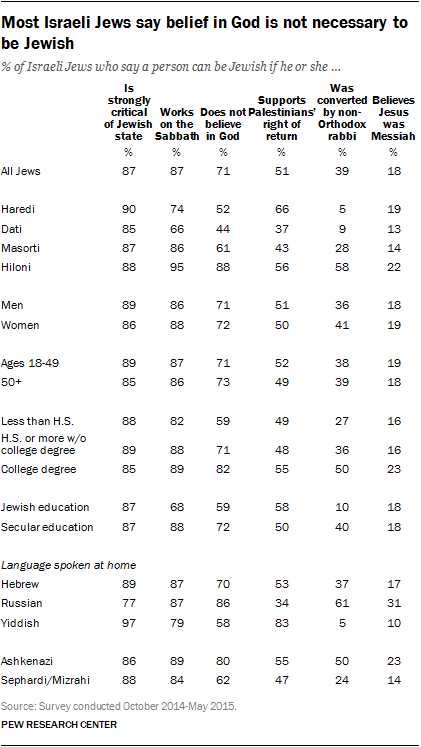

Jews say people can be Jewish even if they work on Sabbath

In addition to asking about qualities that are essential to Jewish identity, the survey also asked Jews in Israel what might disqualify someone from being Jewish.

Large majorities of Jews in Israel across different religious and cultural backgrounds agree that a person can be Jewish even if he or she works on the Sabbath or is strongly critical of the Jewish state.

There is somewhat more disagreement among Jews of different religious backgrounds on whether a person can be Jewish if he or she does not believe in God. Majorities of Hilonim (88%) and Masortim (61%) say not believing in God is compatible with being Jewish, but fewer Haredim (52%) and Datiim (44%) agree with this view.

About half of Israeli Jews say a person can be Jewish even if he/she supports Palestinians’ right of return to the land of Israel (51%), while 40% say supporting Palestinians’ right of return disqualifies a person from being Jewish. On this question, there are stark differences between the two most highly observant Jewish subgroups. Two-thirds of Haredim say a person can be Jewish despite holding this particular political view, while only about half as many Datiim (37%) say a person who supports Palestinians’ right of return can be Jewish.

Roughly four-in-ten Israeli Jews (39%) say a person can be Jewish if they were converted by a non-Orthodox rabbi, although there are major differences among Jewish subgroups on this question. Most Hilonim (58%) say a person can be Jewish in this situation, but only 28% of Masortim, 9% of Datiim and 5% of Haredim agree.

Israeli Jews generally think that a person cannot be Jewish if he/she believes Jesus was the Messiah. About one-in-five Hilonim (22%) and Haredim (19%) and one-in-ten Datiim (13%) and Masortim (14%) say someone who believes in Jesus can still be Jewish.

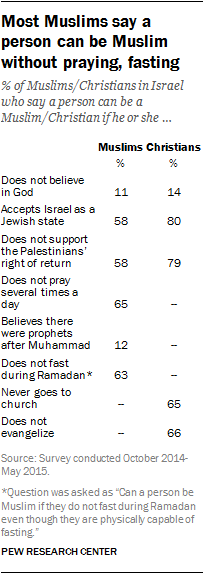

Muslims, Christians say belief in God is essential to being Muslim or Christian

In stark contrast with Jews, few Muslims (11%) or Christians (14%) say that one can deny the existence of God and still be a Muslim or Christian.

In the Islamic tradition, Muhammad is considered the final prophet; few Muslims in Israel (12%) say one can believe that there were prophets after Muhammad and still be a Muslim.

By contrast, most Muslims (58%) and Christians (80%) say a person can accept Israel as a Jewish state and still be a member of their respective religious group.

The survey also asked Muslims and Christians if not supporting the political view that Palestinians who became refugees during and after the 1948 war have the right to return to and own property in Israel (commonly known as Palestinians’ right to return) disqualifies people from being Muslim or Christian.

Majorities say a person can be Muslim (58%) or Christian (79%) even if that person does not support Palestinians’ right of return. (This question was asked in the opposite way for Jews, 51% of whom say a person can be Jewish even if they do support Palestinians’ right of return.)

Overall, most Muslims and Christians say that not practicing certain aspects of their faith does not disqualify people from being members of their religion. For Muslims, nearly two-thirds say a person can be Muslim even if he or she does not pray several times a day (65%) or fast during Ramadan (63%). And similar shares of Christians say people can be Christian even if they never go to church (65%) or do not evangelize (66%).

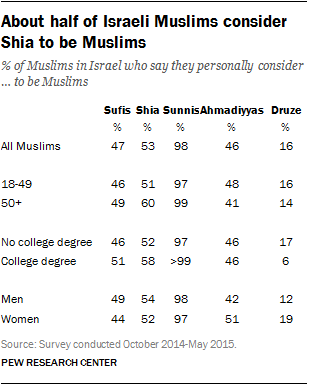

Israeli Muslims divided over whether some groups qualify as Muslims

The survey also asked self-identified Muslim respondents whether they consider members of certain groups to be Muslim.

The vast majority of Israeli Muslims are Sunni, and nearly all surveyed Muslims (98%) say they consider Sunnis to be Muslim. By comparison, about half of Muslims in Israel say Shias (53%), Sufis (47%) and Ahmadiyyas (46%) are Muslims.

In Israel, Druze citizens have a different status from Muslims in some ways. For example, Druze are subject to the military draft and serve in the Israeli armed forces, while Muslims are exempt from serving but may volunteer. But 16% of Muslims say they consider Druze to be Muslims. (For more about Druze history and beliefs, see this sidebar.)

Some of these groups are unfamiliar to many Muslims in Israel. For example, 20% of Muslims declined to give an opinion about Sufis, saying they had never heard about the group. (Sufis tend to be concentrated in South Asia, Africa and some countries in the Middle East.) And 15% of Israeli Muslims say they are not familiar with Ahmadiyyas, a group that has a small presence in some parts of Israel and is generally well integrated into the Israeli Arab community.

When it comes to acceptance of these groups as Muslims, opinions among self-identified Muslims vary little by age, education and gender.