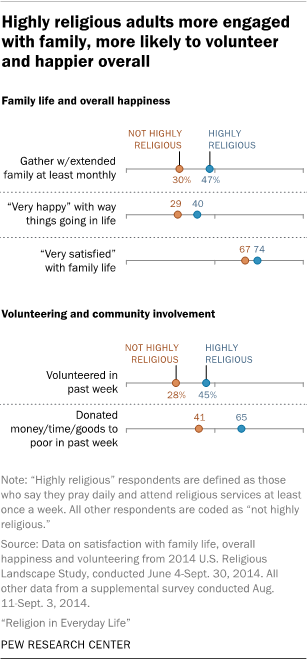

A new Pew Research Center study of the ways religion influences the daily lives of Americans finds that people who are highly religious are more engaged with their extended families, more likely to volunteer, more involved in their communities and generally happier with the way things are going in their lives.

These differences are found not only in the U.S. adult population as a whole but also within a variety of religious traditions (such as between Catholics who are highly religious and those who are less religious), and they persist even when controlling for other factors, including age, income, education, geographic region of residence, marital status and parental status.

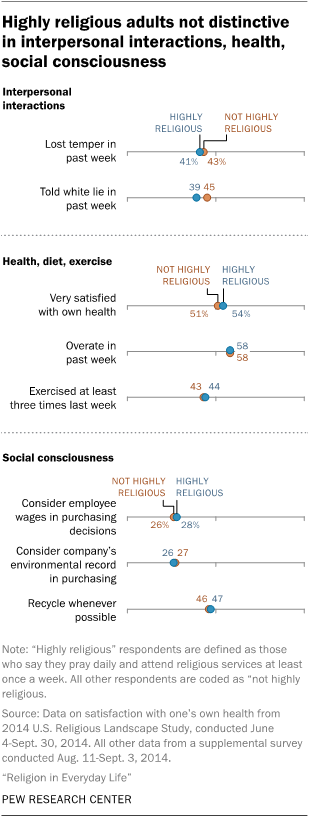

However, in several other areas of day-to-day life – including interpersonal interactions, attention to health and fitness, and social and environmental consciousness – Pew Research Center surveys find that people who pray every day and regularly attend religious services appear to be very similar to those who are not as religious.1

These are among the latest findings of Pew Research Center’s U.S. Religious Landscape Study. The study and this report were made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support for the project from Lilly Endowment Inc.

Two previous reports on the Landscape Study, based on a 2014 telephone survey of more than 35,000 adults, examined the changing religious composition of the U.S. public and described the religious beliefs, practices and experiences of Americans. This new report also draws on the national telephone survey but is based primarily on a supplemental survey among 3,278 participants in the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel, a nationally representative group of randomly selected U.S. adults surveyed online and by mail. The supplemental survey was designed to go beyond traditional measures of religious behavior – such as worship service attendance, prayer and belief in God – to examine the ways people exhibit (or do not exhibit) their religious beliefs, values and connections in their day-to-day lives.2

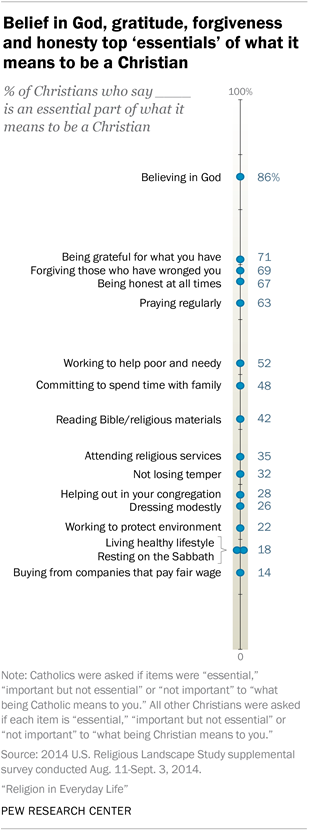

To help explore this question, the survey asked U.S. adults whether each of a series of 16 beliefs and behaviors is “essential,” “important but not essential,” or “not important” to what their religion means to them, personally.

Among Christians, believing in God tops the list, with fully 86% saying belief in God is “essential” to their Christian identity. In addition, roughly seven-in-ten Christians say being grateful for what they have (71%), forgiving those who have wronged them (69%) and always being honest (67%) are essential to being Christian. Far fewer say that attending religious services (35%), dressing modestly (26%), working to protect the environment (22%) or resting on the Sabbath (18%) are essential to what being Christian means to them, personally.

The survey posed similar questions to members of non-Christian faiths and religiously unaffiliated Americans (sometimes called religious “nones”), asking whether various behaviors are essential to “what being a moral person means to you.”3 Among the unaffiliated, honesty (58%) and gratitude (53%) are the attributes most commonly seen as essential to being a moral person. (Findings about non-Christians are discussed in more detail at the end of Chapter 2.)

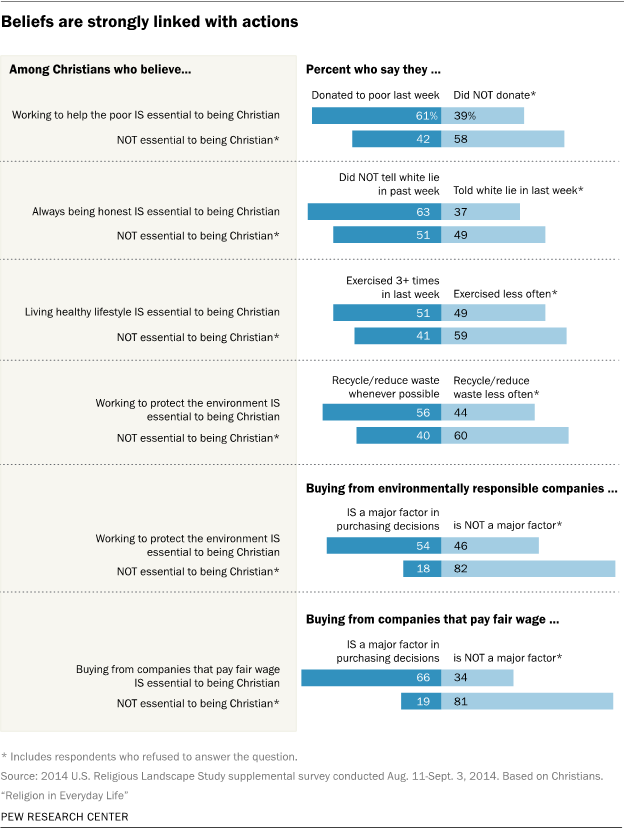

The survey shows a clear link between what people see as essential to their faith and their self-reported day-to-day behavior. Simply put, those who believe that behaving in a particular way or performing certain actions are key elements of their faith are much more likely to say they actually perform those actions on a regular basis.

For example, among Christians who say that working to help the poor is essential to what being Christian means to them, about six-in-ten say they donated time, money or goods to help the poor in the past week. By comparison, fewer Christians who do not see helping the poor as central to their religious identity say they worked to help the poor during the previous week (42%).

The same pattern is seen in the survey’s questions about interpersonal interactions, health and social consciousness. Relatively few Christians see living a healthy lifestyle, buying from companies that pay fair wages or protecting the environment as key elements of their faith. But those who do see these things as essential to what it means to be a Christian are more likely than others to say they live a healthy lifestyle (by exercising, for example), consider how a company treats its employees and the environment when making purchasing decisions, or attempt to recycle or reduce waste as much as possible.

Of course, survey data like these cannot prove that believing certain actions are obligatory for Christians actually causes Christians to behave in particular ways. The causal arrow could point in the other direction: It may be easier for those who regularly engage in particular behaviors to cite those behaviors as essential to their faith. Conversely, it may be harder for those who do not regularly engage in particular activities (such as helping the poor) to describe those activities as essential to their faith. Nevertheless, the survey data suggest that Christians are more likely to live healthy lives, work on behalf of the poor and behave in environmentally conscious ways if they consider these things essential to what it means to be a Christian.

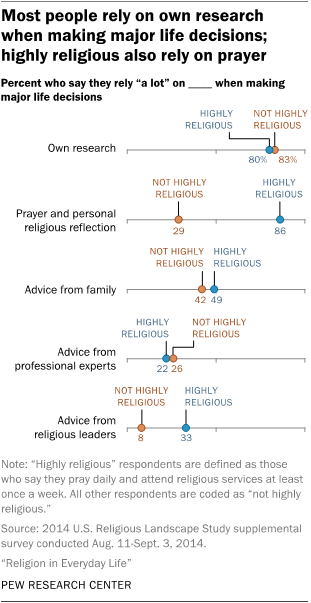

But while relatively few people look to religious leaders for guidance on major decisions, many Americans do turn to prayer when faced with important choices. Indeed, among those who are highly religious, nearly nine-in-ten (86%) say they rely “a lot” on prayer and personal religious reflection when making major life decisions, which exceeds the share of the highly religious who say they rely a lot on their own research.

Other key findings in this report include:

- Three-quarters of adults – including 96% of members of historically black Protestant churches and 93% of evangelical Protestants – say they thanked God for something in the past week. And two-thirds, including 91% of those in the historically black Protestant tradition and 87% of evangelicals, say they asked God for help during the past week. Fewer than one-in-ten adults (8%) say they got angry with God in the past week. (For more details on how Americans say they relate to God, see Chapter 1.)

- One-third of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they thanked God for something in the past week, and one-in-four have asked God for help in the past week. (For more details, see Chapter 1.)

- Nearly half of Americans (46%) say they talk with their immediate families about religion at least once or twice a month. About a quarter (27%) say they talk about religion at least once a month with their extended families, and 33% say they discuss religion as often with people outside their families. Having regular conversations about religion is most common among evangelicals and people who belong to churches in the historically black Protestant tradition. By contrast, relatively few religious “nones” say they discuss religion with any regularity. (For more details on how often Americans talk about religion, see Chapter 1.)

- One-third of American adults (33%) say they volunteered in the past week. This includes 10% who say they volunteered mainly through a church or religious organization and 22% who say their volunteering was not done through a religious organization. (For more details on volunteering, see Chapter 1.)4

- Three-in-ten adults say they meditated in the past week to help cope with stress. Regularly using meditation to cope with stress is more common among highly religious people than among those who are less religious (42% vs. 26%). (For more details on meditation and stress, see Chapter 1.)

- Nine-in-ten adults say the quality of a product is a “major factor” they take into account when making purchasing decisions, and three-quarters focus on the price. Far fewer – only about one-quarter of adults – say a company’s environmental responsibility (26%) or whether it pays employees a fair wage (26%) are major factors in their purchasing decisions. Highly religious adults are no more or less likely than those who are less religious to say they consider a company’s environmental record and fair wage practices in making purchasing decisions. (For more details on how Americans make purchasing decisions, see Chapter 1.)

- Three-quarters of Catholics say they look to their own conscience “a great deal” for guidance on difficult moral questions. Far fewer Catholics say they look a great deal to the Catholic Church’s teachings (21%), the Bible (15%) or the pope (11%) for guidance on difficult moral questions. (For more details, see Chapter 3.)

- One-quarter of Christians say dressing modestly is essential to what being Christian means to them, and an additional four-in-ten say it is “important, but not essential.” (For more details, see Chapter 2.)

- When asked to describe, in their own words, what being a “moral person” means to them, 23% of religious “nones” cite the golden rule or being kind to others, 15% mention being a good person and 12% mention being tolerant and respectful of others. (For more details, see Chapter 2.)

The remainder of this report explores these and other findings in greater depth. Chapter 1 provides greater detail on how Americans from various religious backgrounds say they live their day-to-day lives. Chapter 2 examines the essentials of religious and moral identity – what do Christians see as “essential” to what it means to be a Christian, and what do members of non-Christian faiths and religious “nones” see as essential to being a moral person? Chapter 3 reports on where members of various religious groups say they look for guidance when making major life decisions or thinking about tough moral questions. On most of these questions, the report compares highly religious Americans with those who are less religious and also looks at differences among members of a variety of religious groups. For comparisons of highly religious people with those who are less religious within particular religious groups (e.g., highly religious Catholics vs. less religious Catholics), see the detailed tables.

Profile of those who are highly religious, less religious

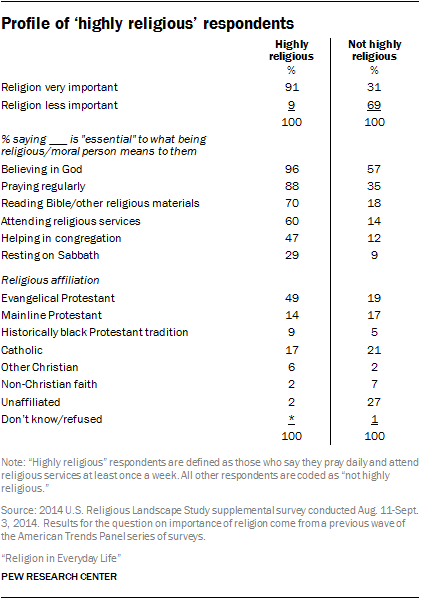

In this report, “highly religious” respondents are defined as those who say they pray daily and attend religious services at least once a week. Overall, 30% of U.S. adults are highly religious by this definition, while 70% are not.5

As this report highlights, these standard measures of traditional religious practice do not capture the full breadth of what it means to be religious; many respondents also say attributes such as gratitude, forgiveness and honesty are essential to what being religious means to them, personally. Nevertheless, these two indicators (prayer and religious attendance) are closely related to a variety of other measures of religious commitment.

For example, nine-in-ten people who are categorized as highly religious (91%) say religion is very important in their lives, and nearly all the rest (7%) say religion is at least somewhat important to them. By contrast, only three-in-ten people who are classified as not highly religious (31%) say religion is very important in their lives, and most of the rest (38%) say religion is “not too” or “not at all” important to them.6

Nearly all people who are highly religious say believing in God is essential to their religious identity (96%), compared with only 57% of people who are not highly religious. Similarly, fully seven-in-ten people who are highly religious say reading the Bible or other religious materials is essential to their religious identity; only 18% of those who are not highly religious say this is vital to their religious identity or to what being a moral person means to them.

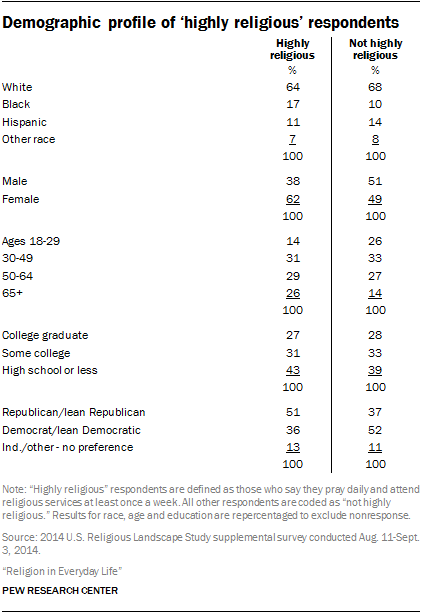

As might be expected, the religious makeup of the highly religious and less religious also are quite distinct. Fully half of highly religious American adults (49%) identify with evangelical Protestant denominations, compared with about one-in-five (19%) of those who are not highly religious. And while only a handful of highly religious people are religiously unaffiliated, about a quarter of less religious respondents (27%) identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.”

There also are important demographic differences between the highly religious and those who are less religious.7 They also are more likely to align with the Republican Party than the Democratic Party, and they are somewhat older, on average, than those who are less religious. However, there are few differences by level of education.