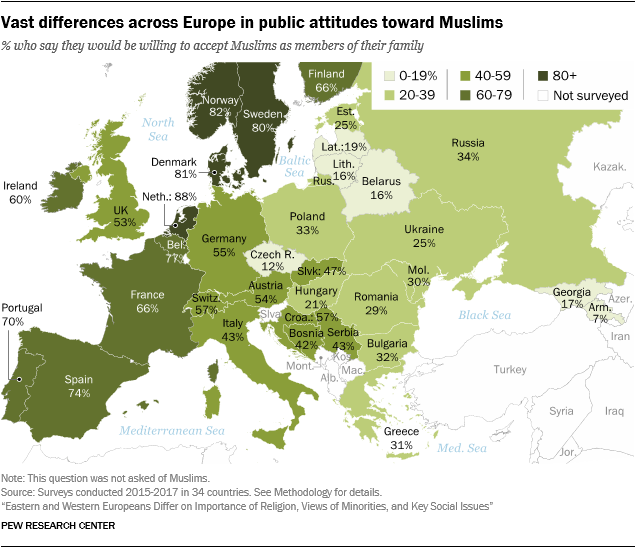

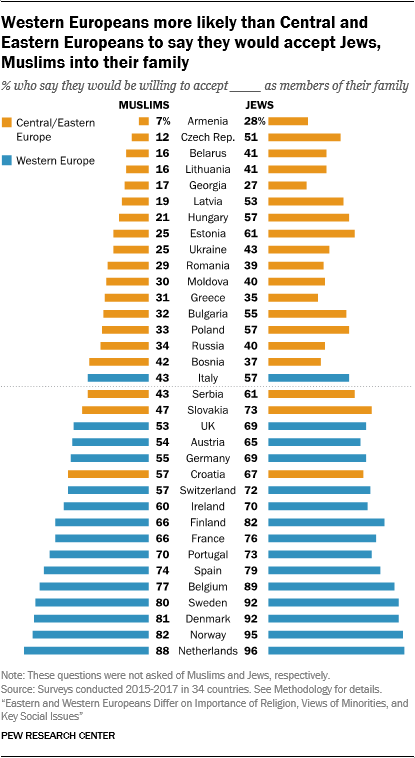

The Iron Curtain that once divided Europe may be long gone, but the continent today is split by stark differences in public attitudes toward religion, minorities and social issues such as gay marriage and legal abortion. Compared with Western Europeans, fewer Central and Eastern Europeans would welcome Muslims or Jews into their families or neighborhoods, extend the right of marriage to gay or lesbian couples or broaden the definition of national identity to include people born outside their country.

These differences emerge from a series of surveys conducted by Pew Research Center between 2015 and 2017 among nearly 56,000 adults (ages 18 and older) in 34 Western, Central and Eastern European countries, and they continue to divide the continent more than a decade after the European Union began to expand well beyond its Western European roots to include, among others, the Central European countries of Poland and Hungary, and the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania.

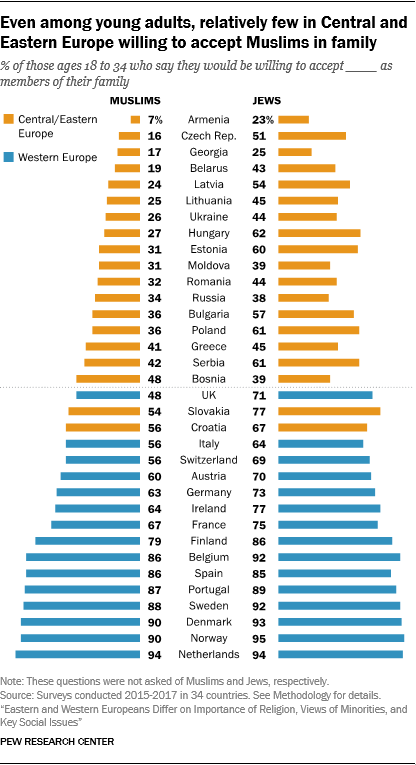

The continental divide in attitudes and values can be extreme in some cases. For example, in nearly every Central and Eastern European country polled, fewer than half of adults say they would be willing to accept Muslims into their family; in nearly every Western European country surveyed, more than half say they would accept a Muslim into their family. A similar divide emerges between Central/Eastern Europe and Western Europe with regard to accepting Jews into one’s family.

In a separate question, Western Europeans also are much more likely than their Central and Eastern European counterparts to say they would accept Muslims in their neighborhoods.1 For example, 83% of Finns say they would be willing to accept Muslims as neighbors, compared with 55% of Ukrainians. And although the divide is less stark, Western Europeans are more likely to express acceptance toward Jews in their neighborhoods as well.

Defining the boundaries of Eastern and Western Europe

The definition and boundaries of Central, Eastern and Western Europe can be debated. No matter where the lines are drawn, however, there are strong geographic patterns in how people view religion, national identity, minorities and key social issues. Particularly sharp differences emerge when comparing attitudes in countries historically associated with Eastern vs. Western Europe.

In countries that are centrally located on the continent, prevailing attitudes may align with popular opinions in the East on some issues, while more closely reflecting Western public sentiment on other matters. For instance, Czechs are highly secular, generally favor same-sex marriage and do not associate Christianity with their national identity, similar to most Western Europeans. But Czechs also express low levels of acceptance toward Muslims, more closely resembling their neighbors in the East. And most Hungarians say that being born in their country and having Hungarian ancestry are important to being truly Hungarian – a typically Eastern European view of national identity. Yet, at the same time, only about six-in-ten Hungarians believe in God, reflecting Western European levels of belief.

In some other cases, Central European countries fall between the East and the West. Roughly half of Slovaks, for example, say they favor same-sex marriage, and a similar share say they would accept Muslims in their family – lower shares than in most Western European countries, but well above their neighbors in the East. And still others simply lean toward the East on most issues, as Poland does on views of national identity and Muslims, as well as same-sex marriage and abortion.

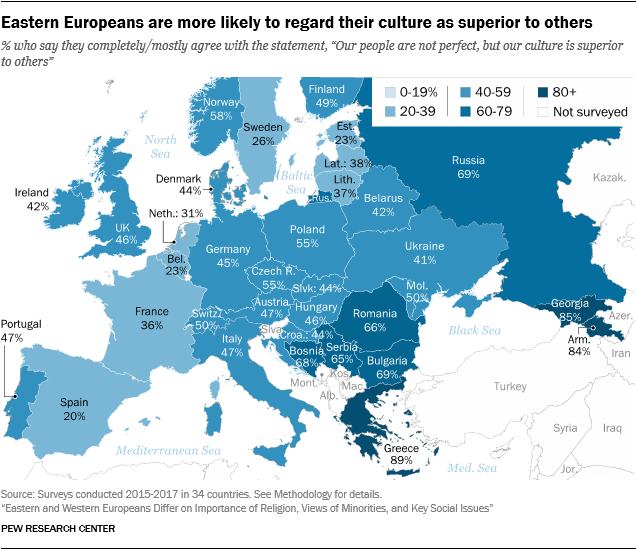

Researchers included Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, the Baltics and the Balkans as part of “Central and Eastern Europe” because all these countries were part of the Soviet sphere of influence in the 20th century. Although Greece was not part of the Eastern bloc, it is categorized in Central and Eastern Europe because of both its geographical location and its public attitudes, which are more in line with Eastern than Western Europe on the issues covered in this report. For example, most Greeks say they are not willing to accept Muslims in their families; three-quarters consider being Orthodox Christian important to being truly Greek; and nearly nine-in-ten say Greek culture is superior to others. East Germany is another unusual case; it was part of the Eastern bloc, but is now included in Western Europe as part of a reunified Germany.

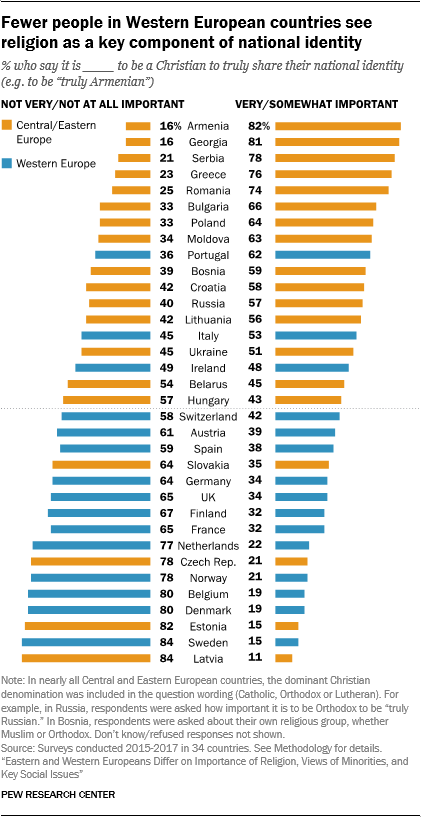

Attitudes toward religious minorities in the region go hand in hand with differing conceptions of national identity. When they were in the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence, many Central and Eastern European countries officially kept religion out of public life. But today, for most people living in the former Eastern bloc, being Christian (whether Catholic or Orthodox) is an important component of their national identity.

In Western Europe, by contrast, most people don’t feel that religion is a major part of their national identity. In France and the United Kingdom, for example, most say it is not important to be Christian to be truly French or truly British.

To be sure, not every country in Europe neatly falls into this pattern. For example, in the Baltic states of Latvia and Estonia, the vast majority of people say being Christian (specifically Lutheran) is not important to their national identity. Still, relatively few express willingness to accept Muslims as family members or neighbors.

But a general East-West pattern is also apparent on at least one other measure of nationalism: cultural chauvinism. The surveys asked respondents across the continent whether they agree with the statement, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others.” While there are exceptions, Central and Eastern Europeans overall are more inclined to say their culture is superior. The eight countries where this attitude is most prevalent are all geographically in the East: Greece, Georgia, Armenia, Bulgaria, Russia, Bosnia, Romania and Serbia.

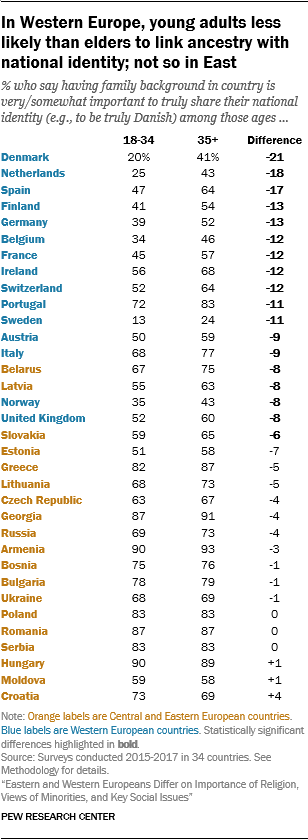

People in Central and Eastern Europe also are more likely than Western Europeans to say being born in their country and having family background there are important to truly share the national identity (e.g., to be truly Romanian; see here.).

Taken together, these and other questions about national identity, religious minorities and cultural superiority would seem to indicate a European divide, with high levels of religious nationalism in the East and more openness toward multiculturalism in the West. Other questions asked on the survey point to a further East-West “values gap” with respect to key social issues, such as same-sex marriage and legal abortion.

Differences over the meaning of ‘European values’

Is Christianity a “European value?” What about secularism? And how about multiculturalism and open borders?

Leaders often cite European values when defending their stances on highly charged political topics. But the term “European values” can mean different things to different people. For some, it conjures up the continent’s Christian heritage; for others, it connotes a broader political liberalism that encompasses a separation between church and state, asylum for refugees, and democratic government.

For the European Union, whose members include 24 of the 34 countries surveyed in this report, the term “European values” tends to signify what Americans might consider liberal ideals.2 The “Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union” includes respect for cultural and religious diversity; prohibitions against discrimination based on religion and sexual orientation; the right to asylum for refugees; and guarantees of freedom of movement within the EU.3

These rights and principles are part of the EU’s legal system and have been affirmed in decisions of the European Court of Justice going back decades.4 But the membership of the EU has changed in recent years, beginning in 2004 to spread significantly from its historic western base into Central and Eastern Europe. Since that year, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia have joined the EU. In many of these countries, the surveys show that people are less receptive to religious and cultural pluralism than they are in Western Europe – challenging the notion of universal assent to a set of European values.

These are not the only issues dividing Eastern and Western Europe.5 But they have been in the news since a surge in immigration to Europe brought record levels of refugees from predominantly Muslim countries and sparked fierce debates among European leaders and policymakers about border policies and national values.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has articulated one strain of opposition to the EU’s conception of European values, declaring in July 2018 that “Central Europe … has a special culture. It is different from Western Europe.” Every European country, he said, “has the right to defend its Christian culture, and the right to reject the ideology of multiculturalism,” as well as the right to “reject immigration” and to “defend the traditional family model.” Earlier in the year, in an address to the Hungarian parliament, he criticized the EU stance on migration: “In Brussels now, thousands of paid activists, bureaucrats and politicians work in the direction that migration should be considered a human right. … That’s why they want to take away from us the right to decide with whom we want to live.”

This is not to suggest that support for multiculturalism is universal even in Western Europe. Substantial shares of the public in many Western European countries view being Christian as a key component of their national identity and say they would not accept Muslims or Jews as relatives. And of course, the United Kingdom voted in 2016 to leave the European Union, which many have suggested came in part due to concerns about immigration and open borders. But on the whole, people in Western European countries are much more likely than their neighbors in the East to embrace multiculturalism.

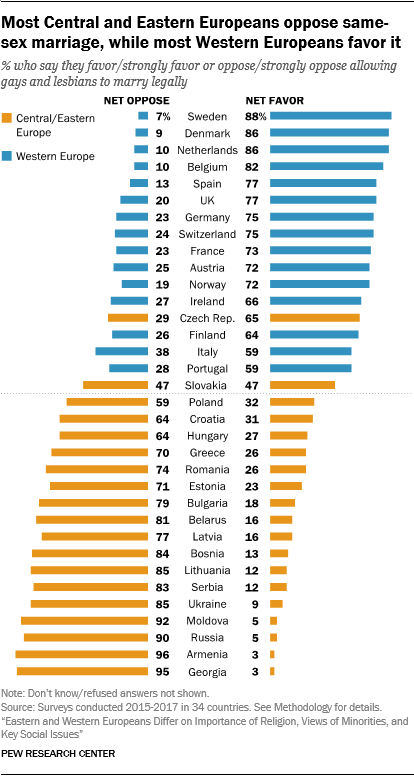

Majorities favor same-sex marriage in every Western European country surveyed, and nearly all of these countries have legalized the practice. Public sentiment is very different in Central and Eastern Europe, where majorities in nearly all countries surveyed oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. None of the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed allow same-sex marriages.

In some cases, these views are almost universally held. Fully nine-in-ten Russians, for instance, oppose legal same-sex marriage, while similarly lopsided majorities in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden favor allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry legally.

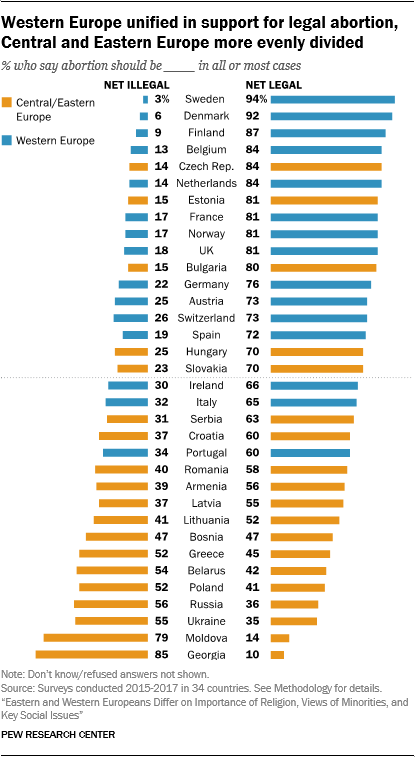

Even though abortion generally is legal in both Central/Eastern and Western Europe, there are regional differences in views on this topic, too.6 In every Western European nation surveyed – including the heavily Catholic countries of Ireland, Italy and Portugal – six-in-ten or more adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

But in the East, views are more varied. To be sure, some Central and Eastern European countries, such as the Czech Republic, Estonia and Bulgaria, overwhelmingly favor legal abortion. But in several others, including Poland, Russia and Ukraine, the balance of opinion tilts in the other direction, with respondents more likely to say that abortion should be mostly or entirely illegal.

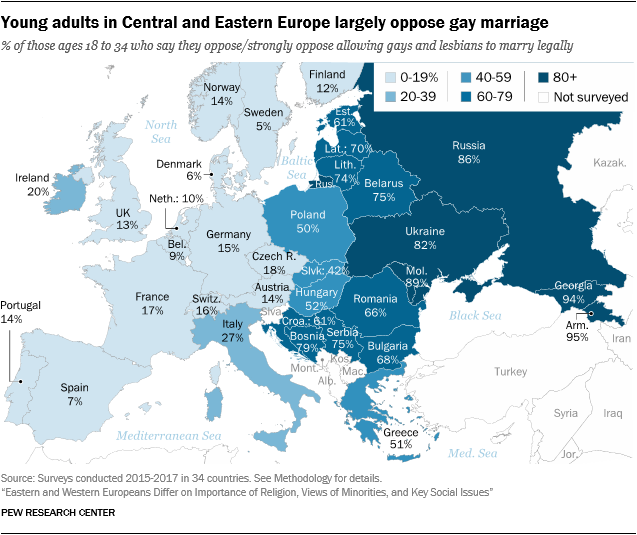

Survey results suggest that Europe’s regional divide over same-sex marriage could persist into the future: Across most of Central and Eastern Europe, young adults oppose legalizing gay marriage by only somewhat narrower margins than do their elders.

For example, 61% of younger Estonians (ages 18 to 34) oppose legal gay marriage in their country, compared with 75% of those 35 and older. By this measure, young Estonian adults are still six times as likely as older adults in Denmark (10%) to oppose same-sex marriage. This pattern holds across the region; young adults in nearly every Central and Eastern European country are much more conservative on this issue compared with both younger and older Western Europeans.

In addition, when it comes to views about Muslims and Jews, young adults in most countries in Central and Eastern Europe are no more accepting than their elders.

Consequently, those in this younger generation in Central and Eastern Europe are much less likely than their peers in Western Europe to express openness to having Muslims or Jews in their families. For example, 36% of Polish adults under 35 say they would be willing to accept Muslims in their family, far below the two-thirds of young French adults who say they would be willing to have Muslims in their family – mirroring the overall publics in those countries.

These are among the findings of Pew Research Center surveys conducted across Central and Eastern Europe in 2015 and 2016 and Western Europe in 2017.7

The Center previously has published major reports on both surveys: “Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe” and “Being Christian in Western Europe.” Many of the same questions were asked in both regions, allowing for the comparisons in this report. The Central and Eastern Europe surveys were conducted via face-to-face-interviews, while Western Europeans were surveyed by telephone. See Methodology for details.

The rest of this report will look at more cross-regional comparisons, including:

- Identification with Christianity has declined over time across Western Europe, but this is not the case in much of Central and Eastern Europe. In most countries in the East, the share of Christians has remained fairly stable in recent generations. And in a few countries, including Russia, Christians have increased as a percentage of the population.

- Compared with the rest of the world, the entire European continent has relatively low levels of traditional religious practice (e.g., church attendance, prayer), but they are slightly higher in Central and Eastern Europe than in the West. On balance, Central and Eastern Europeans also are more likely to say they believe in God, and to express some New Age or folk religious beliefs – such as that certain people can cast curses or spells that cause bad things to happen to someone (the “evil eye”).

- Across the continent, Europeans mostly say religion and government should be kept separate. But this view is more widespread in Western Europe, while several Central and Eastern European countries are more divided. For instance, 46% of Romanians say their government should promote religious values and beliefs.

- In addition to the importance of religion to national identity, the surveys also asked about several other possible elements of national identity. People throughout the continent say it is important to respect national institutions and laws and speak the dominant national language to be a true member of their country, but Central and Eastern Europeans are especially likely to say that nativist elements of national identity – being born in a country and having family ancestry there – are very important.

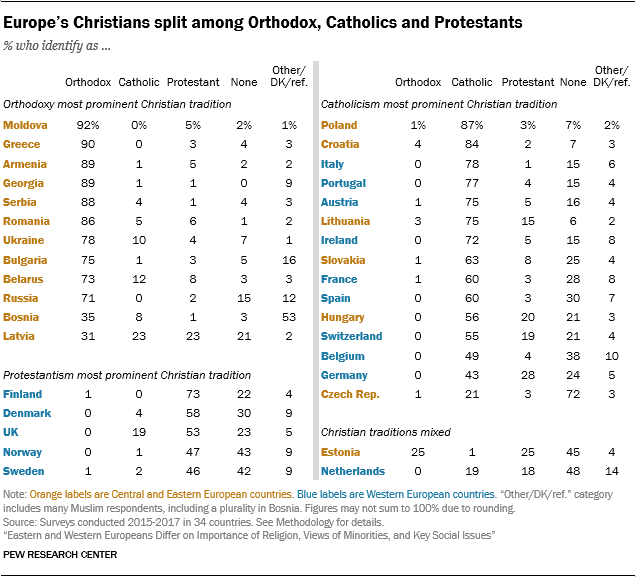

Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Protestantism are each prominent in different parts of Europe

Christianity has long been the prevailing religion in Europe, and it remains the majority religious affiliation in 27 of the 34 countries surveyed. But historical schisms underlie this common religious identity: Each of the three major Christian traditions – Catholicism, Protestantism and Orthodoxy – predominates in a certain part of the continent.

Orthodoxy is the dominant faith in the East, including in Greece, Russia, the former Soviet republics of Moldova, Armenia, Georgia, Ukraine and Belarus, and other former Eastern bloc countries such as Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria. Catholic-majority countries are prevalent in the central and southwestern parts of Europe, cutting a swath from Lithuania through Poland, Slovakia and Hungary, and then extending westward across Croatia, Austria, Italy and France to the Iberian Peninsula. And Protestantism is the dominant Christian tradition in much of Northern Europe, particularly Scandinavia.

There are substantial populations belonging to non-Christian religions – particularly Islam – in many European countries. In Bosnia, roughly half of the population is Muslim, while Russia and Bulgaria have sizable Muslim minority populations. But in most other countries surveyed, Muslims and Jews make up relatively small shares of the population, and surveys often are not able to reliably measure their precise size.

In addition, all the Western European countries surveyed have sizable populations of religiously unaffiliated people – those who identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” collectively sometimes called “nones.” “Nones” make up at least 15% of the population in every Western European country surveyed, and they are particularly numerous in the Netherlands (48%), Norway (43%) and Sweden (42%). On balance, there are smaller shares of “nones” – and larger shares of Christians – in Central and Eastern Europe, though a plurality of Estonians (45%) are unaffiliated, and the Czech Republic is the only country surveyed on the entire continent where “nones” form a majority (72%).

Christian affiliation has declined in Western Europe

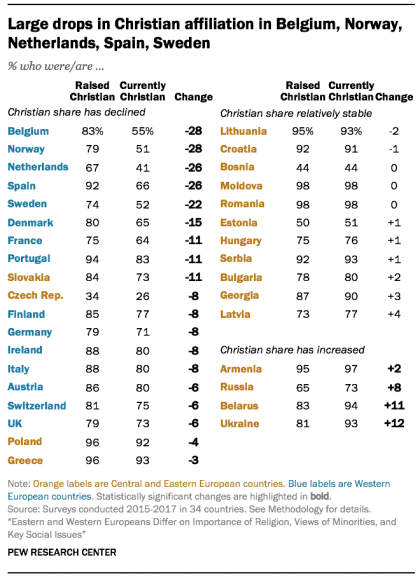

The lower Christian shares in Western Europe reflect how the region’s religious landscape has been changing within the lifetimes of survey respondents.

While large majorities across the continent say they were baptized Christian, and most European countries still have solid Christian majorities, the survey responses indicate a significant decline in Christian affiliation throughout Western Europe. By contrast, this trend has not been seen in Central and Eastern Europe, where Christian shares of the population have mostly been stable or even increasing.

Indeed, in a part of the region where communist regimes once repressed religious worship, Christian affiliation has shown a resurgence in some countries since the fall of the USSR in 1991. In Ukraine, for example, more people say they are Christian now (93%) than say they were raised Christian (81%); the same is true in Russia, Belarus and Armenia. In most other parts of Central and Eastern Europe, Christian shares of the population have been relatively stable by this measure.

Meanwhile, far fewer Western Europeans say they are currently Christian than say they were raised Christian. In Belgium, for example, 55% of respondents currently identify as Christian, compared with 83% saying they were raised Christian.

What are the reasons for these opposing patterns on different sides of the continent? Some appear to be political: In Russia and Ukraine, the most common explanation given by those who were raised without a religion but are now Orthodox is that religion has become more acceptable in society. Another important reason is a connection with their national heritage.

In Western Europe, there are a variety of reasons why many adults who were raised Christian have become unaffiliated. Most of these adults say they “gradually drifted away from religion,” though many also say they disagreed with church positions on social issues like homosexuality and abortion, and/or that they stopped believing in religious teachings.

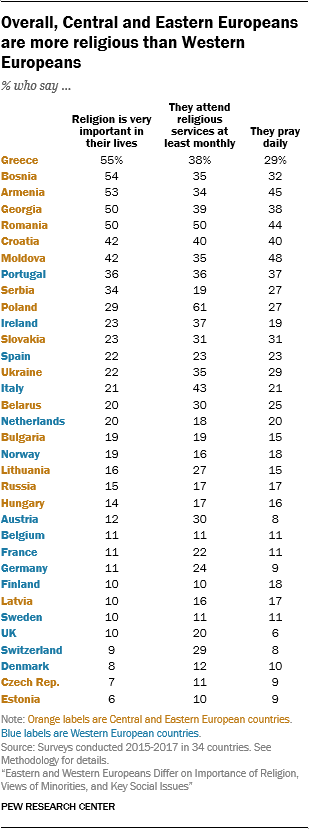

Religious commitment particularly low in Western Europe

Not only is religious affiliation on the decline in Western Europe, religious commitment also is generally lower there than in Central and Eastern Europe.

This is not to say that Central and Eastern Europeans are very religious by conventional measures of religious behavior. Europeans throughout the continent generally show far less religious commitment than adults previously surveyed in other regions.8

That said, on balance, Central and Eastern Europeans are more likely than Western Europeans to say that religion is very important in their lives, that they attend religious services at least monthly, and that they pray every day.

For example, fully half or more of adults in Greece, Bosnia, Armenia, Georgia and Romania say religion is very important in their lives, compared with about one-in-ten in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and several other Western European countries. Similarly, roughly three-in-ten Slovaks, Greeks and Ukrainians say they pray daily, compared with 8% in Austria and Switzerland. Western Europeans also are more likely than their neighbors in the East to say they never pray (e.g., 62% in Denmark vs. 28% in Russia).

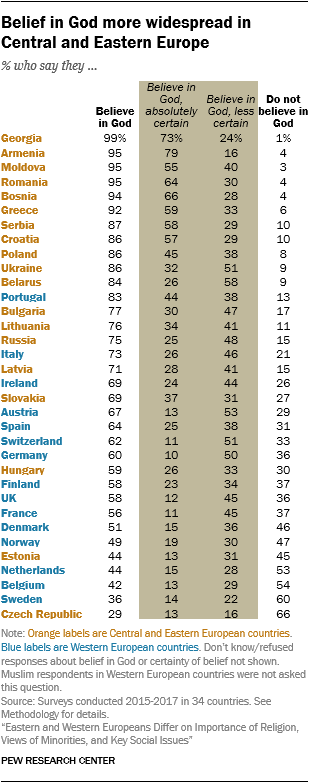

Substantial shares in Western Europe don’t believe in God

Western Europeans also express belief in God at lower levels than people in Central and Eastern Europe, where large majorities say they believe in God – including overwhelming shares in several countries, such as Georgia, Armenia, Moldova and Romania. Among the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed, there are only three exceptions where fewer than two-thirds of adults say they believe in God: Hungary (59%), Estonia (44%) and the Czech Republic (29%).

By contrast, fewer than two-thirds of adults in most Western European countries surveyed say they believe in God, and in some countries with large populations of “nones,” such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Sweden, fewer than half of adults believe in God.

Western Europeans also are less likely to say they are certain of their belief in God. Among the Western European countries surveyed, only in Portugal (44%) do more than three-in-ten say they are absolutely certain that God exists. But majorities in several of the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed express such certainty about God’s existence, including in Romania (64%), Greece (59%) and Croatia (57%).

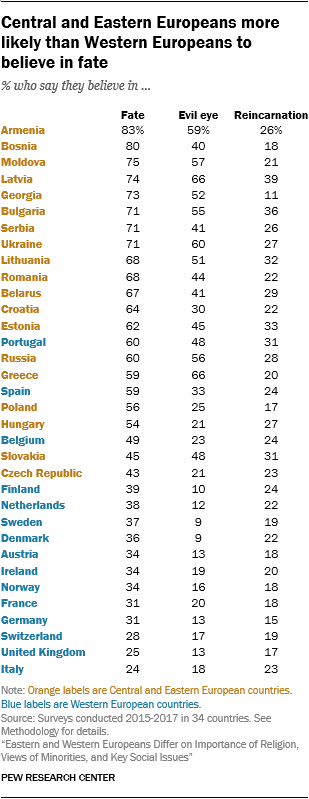

Majorities in most Central and Eastern European countries believe in fate

In addition to belief in God, Central and Eastern Europeans are more likely than Western Europeans to express belief in fate (that the course of life is largely or wholly preordained), as well as in some phenomena not typically linked with Christianity, including the “evil eye” (that certain people can cast curses or spells that cause bad things to happen to someone).

Majorities in most Central and Eastern European countries surveyed say they believe in fate, including about eight-in-ten in Armenia (83%) and Bosnia (80%). In Western Europe, far fewer people believe their lives are preordained – roughly four-in-ten or fewer in most of the countries surveyed.

Belief in the evil eye is also common in Central and Eastern Europe. This belief is most widespread in Greece (66%), Latvia (66%), Ukraine (60%), Armenia (59%), Moldova (57%), Russia (56%) and Bulgaria (55%).

In fact, the levels of belief in the evil eye across Central and Eastern Europe are comparable to those found in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, where indigenous religions have had a broad impact on the respective cultures. (See “Religion in Latin America: Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region” and “Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa.”) In Western Europe, on the other hand, in no country does a majority express belief in the evil eye.

Levels of belief in reincarnation are more comparable across the region. In most Central and Eastern European countries surveyed, a quarter or more say they believe in reincarnation – that is, that people will be reborn in this world again and again. In many Western European countries surveyed, roughly one-fifth of the population expresses belief in reincarnation, a concept more closely associated with Eastern religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism than with Christianity.

Prevailing view across Europe is that religion and government should be separate

Europeans across the continent are largely united in support of a separation between religion and government. More than half of adults in most countries say religion should be kept separate from government policies, rather than the opposing view that government policies should support religious values and beliefs.

In seven Central and Eastern European countries, however, the view that church and state should be separate falls short of a majority position. This includes Armenia and Georgia – where the balance of opinion favors government support for religious values and beliefs – as well as Russia, where 42% of adults say the government should promote religion.

In Western Europe, meanwhile, majorities in nearly every country surveyed say religion should be kept separate from government policies.

Age differences are stronger in Western Europe than in Eastern Europe on this issue: Younger adults across most of Western Europe are more likely than those ages 35 and older to prefer separation of church and state. In Central and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, younger and older adults express roughly similar views on this question.

Europe split on importance of ancestry to national identity, united on importance of speaking national language

While majorities in most Central and Eastern European countries tie being Christian to being truly Serbian, Polish, etc. (see here), majorities in all of these countries view being born in their country and having ancestry there as important components of national identity.

For example, 83% of adults in Hungary and 82% of adults in Poland say it is “very” or “somewhat” important to have been born in their country to be “truly Hungarian” or “truly Polish.” And 72% of Russians say it is important to have Russian family background to be “truly Russian.”

On balance, adults in Western European countries are less likely to view these nativist elements as important to national identity. For example, majorities in Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway say it is “not very” or “not at all” important to be born in their country or have family background there to be “truly Swedish,” etc.

But not everyone across Western Europe feels this way. In Portugal, for example, the vast majority of adults say that being born in Portugal (81%) and having a Portuguese family background (80%) are very or somewhat important to being “truly Portuguese.” These sentiments also are widespread among adults in Italy and Spain.

The two sides of Europe do not appear to be moving closer on these questions with younger generations. In fact, the opposite is true: In Western Europe, young adults (ages 18 to 34) are less likely than their elders to regard birthplace and ancestry as crucial to national identity, while in Central and Eastern Europe, young adults and older people are about equally likely to feel this way. In Spain, for example, only about half of adults under 35 (47%) say having Spanish ancestry is important to being Spanish, compared with 64% of older Spaniards. In Ukraine, meanwhile, young adults and older adults look very similar on this question (68% vs. 69%).

Concerning the importance of family background to national identity, there is a bigger gap between young adults in Western Europe and young adults in Central and Eastern Europe than between the adult populations as a whole.

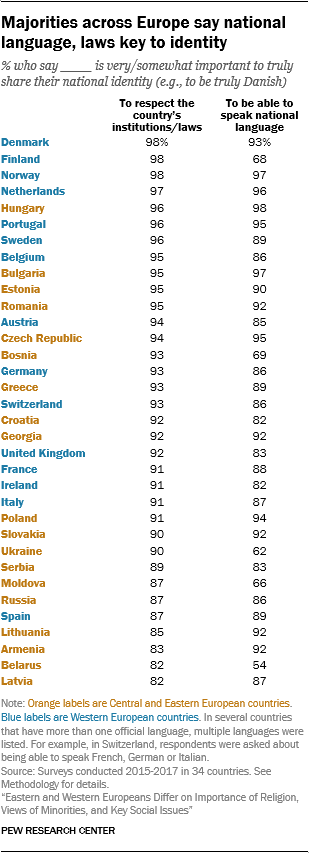

While public opinion on the importance of religion, birthplace and ancestry to national identity is different in Central and Eastern Europe than it is in the West, people throughout the continent largely agree on some other elements of national belonging. Adults in both regions say it is important to respect their country’s institutions and laws and to be able to speak the national language to truly share their national identity.

In fact, overwhelming majorities of adults in every European country surveyed – East and West alike – say it is important to respect the laws of their country in order to truly belong. For example, 98% of Danes, 96% of Hungarians and 87% of Russians say it is important to respect their institutions and laws to truly be Danish, Hungarian or Russian.

And large shares in both Eastern and Western European countries say speaking the national language is important to sharing their national identity. For example, in the Netherlands, 96% of adults say speaking Dutch is important for being truly Dutch. And in Georgia, 92% of adults say it is important to speak Georgian to truly share their national identity. There are a few countries, however, where this sentiment is somewhat less common: Only about two-thirds of adults in Moldova, Finland and Bosnia say speaking the national language is important to truly belonging to their country, as do only 62% of Ukrainians and 54% of Belarusians. This may reflect the fact that multiple languages are spoken in these countries, including large numbers of Russian speakers in Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus.