Race shapes Black Americans’ personal and religious lives. Nearly seven-in-ten say that being Black is very important to how they think about their own identity. Likewise, across religious groups, roughly three-quarters say that opposing racism is an essential part of their faith, and seven-in-ten religiously unaffiliated adults say this is essential to being a moral person. And, as discussed in Chapter 2, nearly half of Black Americans who attended religious services in the 12 months prior to the survey report that they have heard sermons on race or racial inequality at their houses of worship.

Though race shapes Black Americans’ identities and religious lives in many ways, fewer than half say it is essential for houses of worship to offer a sense of racial pride or affirmation. And a third of Black Americans say that historically Black congregations should try to preserve their traditional racial character; most say that historically Black congregations should try to become more racially and ethnically diverse. Additionally, if they were to seek out a new house of worship, only about one-in-seven Black Americans say that it would be very important for most other attendees or senior religious leaders to be Black. These patterns also hold among Black Protestants who currently attend Black churches.

The survey also finds that Black Americans report experiencing racial discrimination outside of religious contexts much more than in religious settings. And across religious groups, most Black Americans believe that racial discrimination is the main reason that Black people cannot get ahead in society.

The rest of this chapter looks more closely at how race and religion intersect in Black Americans’ lives.

Race, identity and religion

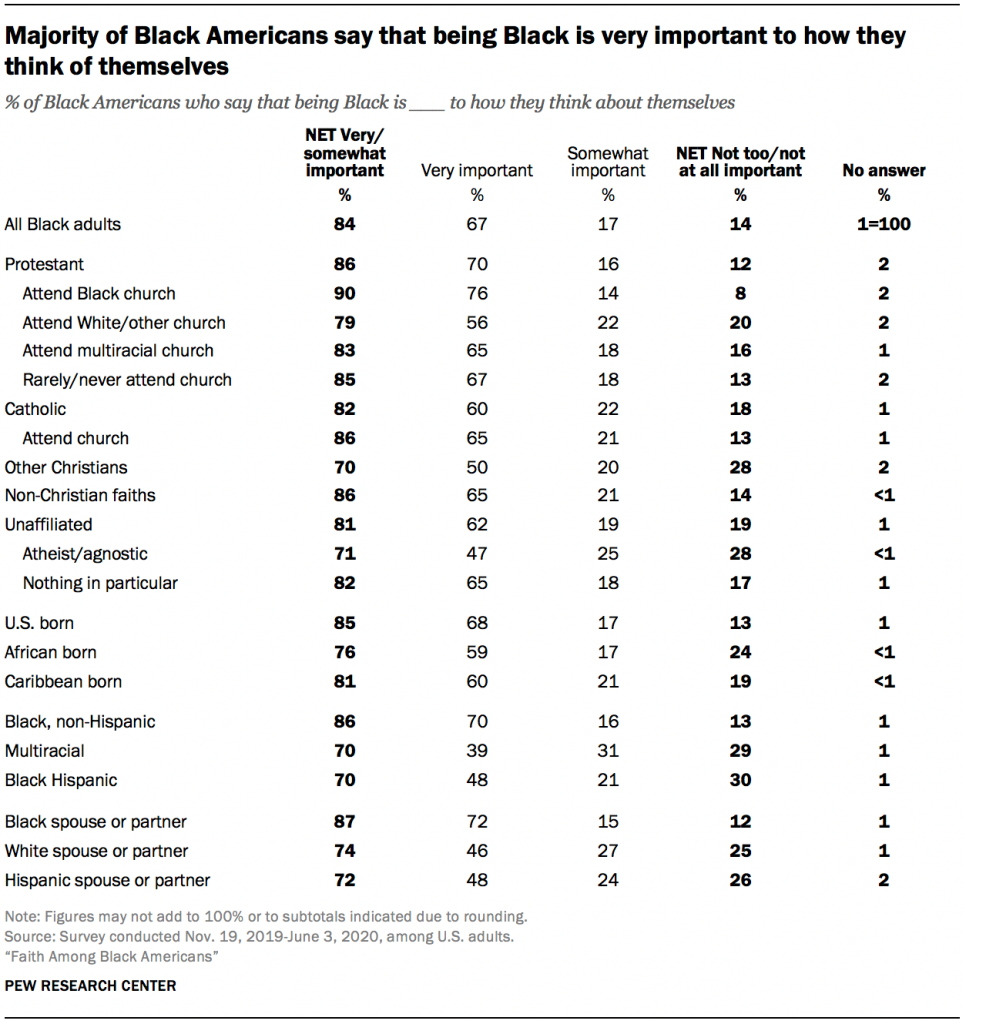

Two-thirds of Black Americans say that being Black is a very important part of how they think about themselves. Black Protestants (70%) are somewhat more likely than Catholics (60%) and the religiously unaffiliated (62%) to say that being Black is a very important part of their personal identity, though majorities in all three groups say this.

Among Protestants, three-quarters of those who attend Black churches (76%) say that being Black is very important to how they think of themselves, as do 65% of those who go to multiracial churches and 56% of those who attend White or other race churches.

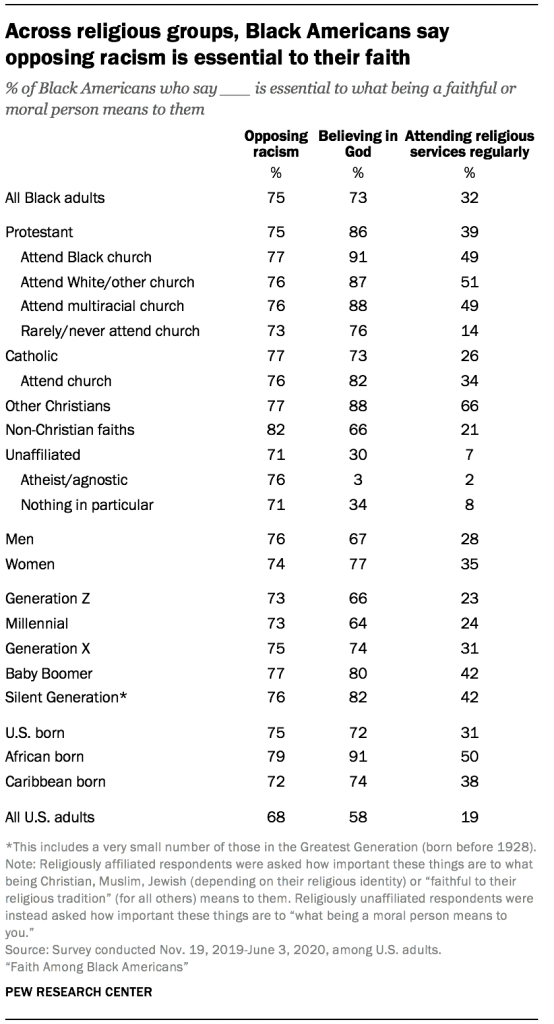

Religiously affiliated respondents were asked whether opposing racism is essential to their faith, and large majorities of Protestants, Catholics, other Christians and members of non-Christian faiths say that it is. Across religious groups, far fewer Black Americans say attending religious services is essential. (See Chapter 3 for more details about what respondents see as central to their faith or sense of morality.)

About seven-in-ten religiously unaffiliated Black Americans, meanwhile, say that opposing racism is essential to what being a moral person means to them (71%).

The importance of race in congregations

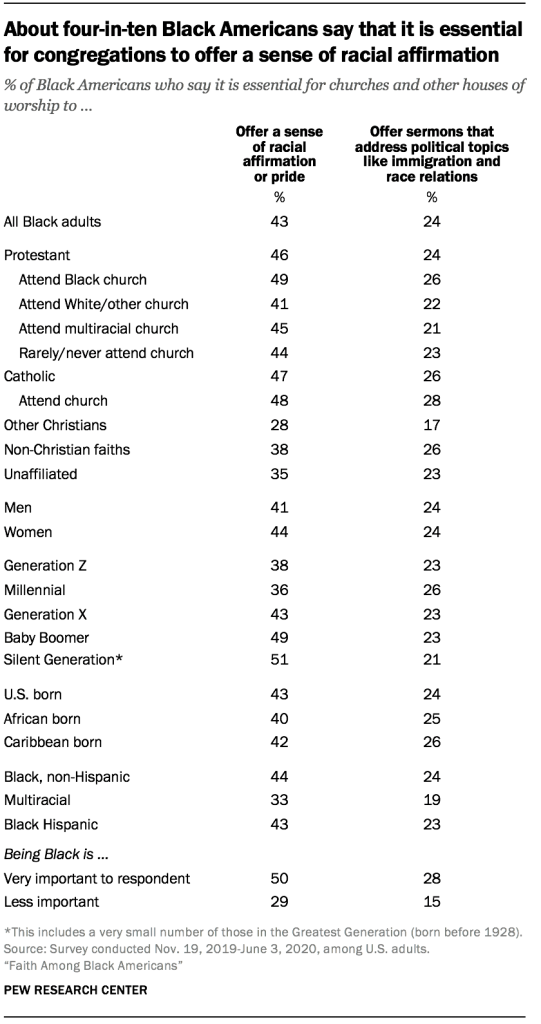

About four-in-ten Black Americans (43%) say that it is essential for houses of worship to offer “a sense of racial affirmation or pride” – lower than the shares who say it is essential for congregations to offer spiritual comfort (72%), a sense of community (71%), and help for the needy with bills, housing and food (55%). (See Chapter 5 for more details about what respondents think is essential for churches or other places of worship to offer.)

Roughly equal shares of Black Protestants (46%) and Catholics (47%) say it is essential that houses of worship offer a sense of racial affirmation. Among Protestants, there are only modest differences on this question between those who attend Black churches (49%) and White or other race churches (41%).

Black Americans who also identify with another race are less likely than single-race non-Hispanic Black adults to say that it is essential for congregations to provide a sense of racial affirmation. And half of those who say being Black is very important to how they think of themselves say it is essential for congregations to provide this, compared with 29% of those who say being Black is less central to their personal identity. Meanwhile, about half of Black Baby Boomers (49%) and those in older generations (51%) say that it is essential that houses of worship offer a sense of racial pride, higher than each of the younger generations.

Fewer Black Americans (24%) say it is essential that houses of worship offer sermons on political topics like immigration and race relations. At the same time, Black Americans are more likely than U.S. adults overall (13%) to express this view, as well as to say racial affirmation from houses of worship is essential to them (26% of U.S. adults overall say this).

Black congregations and diversity

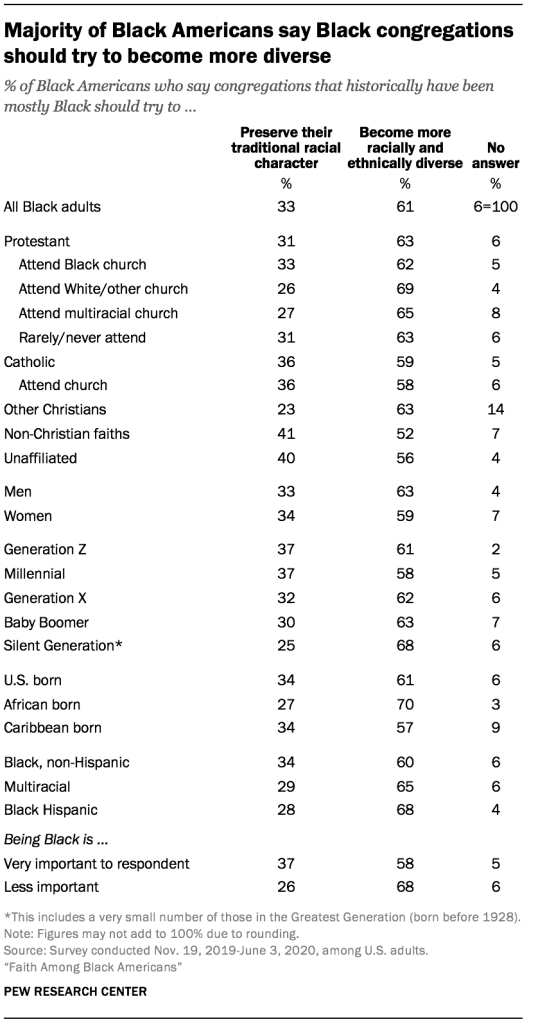

While race is important to Black Americans’ personal identities and faith, large numbers of Black Americans are open to the prospect of diversification within historically Black congregations. About six-in-ten Black Americans say that historically Black congregations should try to “become more racially and ethnically diverse,” while one-third say historically Black congregations should try to “preserve their traditional racial character.”

Protestants and Catholics have similar views on this issue. And among Black Protestants, those who attend White or other race churches are only a little more likely than those who attend Black churches to say that Black congregations should diversify (69% vs. 62%).

Black adults who were born in Africa (70%) are more likely to hold this view than those born in the United States (61%) or the Caribbean (57%). Black Americans who have White spouses also are more inclined to say historically Black congregations should diversify (73%) compared with those who have Black (62%) or Hispanic (61%) spouses. Those who identify as Black alone (60%) are somewhat less likely than those who identify as Black and Hispanic (68%) to say that historically Black congregations should diversify.

Age also factors into whether Black Americans think historically Black congregations should diversify, with Gen Zers and Millennials more likely than those in the Silent Generation to say that Black churches should try to preserve their traditional racial character.

Looking for a new congregation

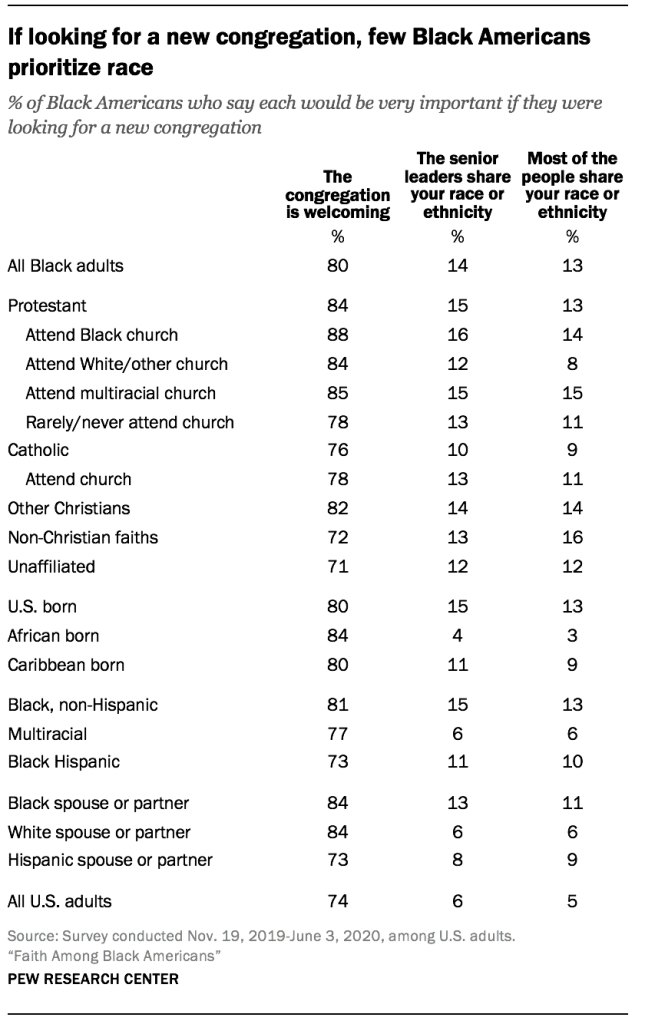

When asked what sorts of things they would prioritize if they were to find themselves looking for a new congregation, 14% of Black Americans say it would be “very important” to them to find a house of worship with Black senior religious leaders, and a similar share (13%) say it would be “very important” to find a congregation where most attendees are Black. While about one-in-five say each of these factors is “somewhat important,” most Black Americans say these factors are either “not too important” or “not at all important.” By comparison, eight-in-ten Black Americans say it would be very important that the congregation be welcoming, and 77% say the same about the congregation having inspiring sermons. (See Chapter 2 for more details about how Black Americans evaluate each of these factors.)

Black Protestants are modestly more inclined than Black Catholics to say that if they were looking for a new congregation, it would be important to them that most attendees and religious leaders be Black. Still, relatively small shares of Protestants who attend different types of congregations would prioritize the race of attendees and religious leaders if they were searching for a new church.

Adults who identify solely as Black and those who are Black and Hispanic are a bit more likely than those who are multiracial to say it would be very important to find a congregation where most senior religious leaders are Black.

Black Americans who were born in the United States and the Caribbean are more likely than immigrants from Africa to say that it would be important that a new congregation have Black senior religious leaders and Black attendees. And Black Americans with Black spouses or partners are more likely than those with White spouses or partners to say this.

Across all of these groups, however, no more than about one-in-seven say it would be very important to them to find a new congregation where most attendees or the senior religious leaders are Black.

Black Americans are slightly more likely than U.S. adults overall to say they would prioritize finding a house of worship where most other attendees (13% vs. 5%) and senior religious leaders (14% vs. 6%) share their race.

Racial discrimination in religious settings and society

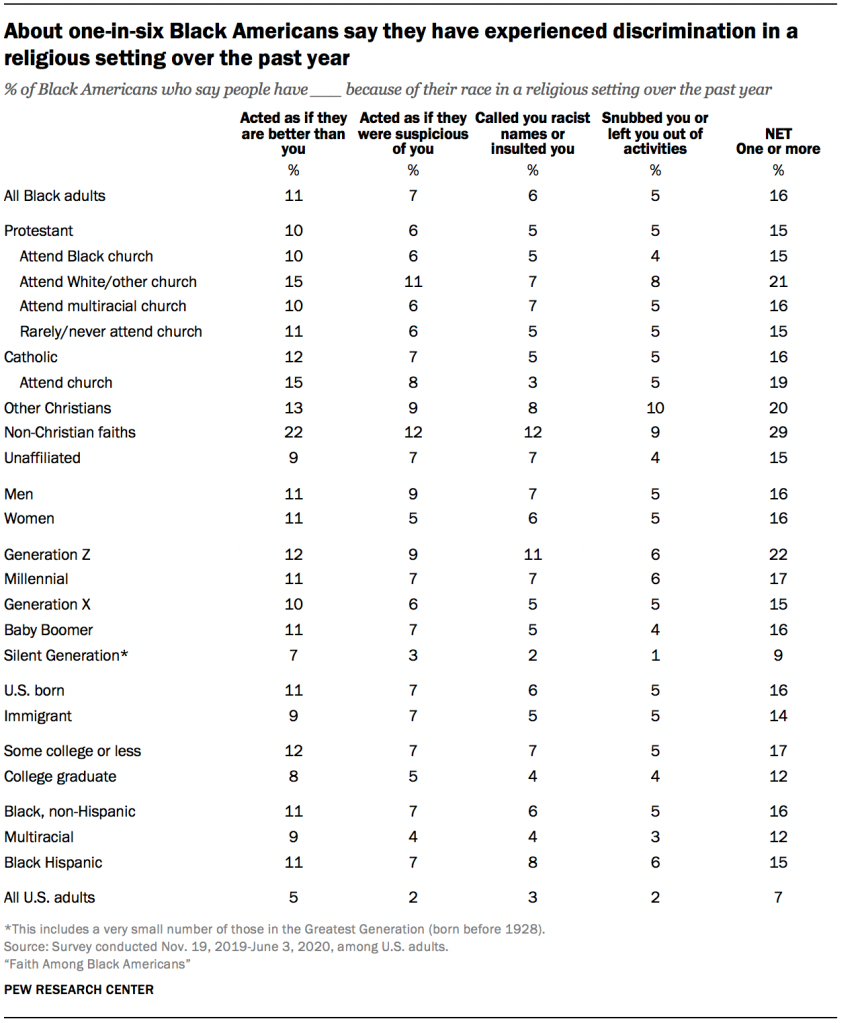

Roughly one-in-six Black Americans (16%) say that they experienced at least one form of racial discrimination in religious settings in the 12 months prior to the survey. The survey asked whether people have had others act as if they are better than them (11%), or if they have been treated suspiciously (7%), called racist names or insulted (6%), or snubbed in social settings (5%) because of their race.

Among Black adults who have experienced discrimination in a religious setting, three-in-ten say this has happened only in a congregation that is not their own, 23% say it has happened only in their own house of worship, and 31% say it has happened both in their own house of worship and in other religious settings; 16% did not answer the question. Because this question was only asked of the roughly one-in-six Black Americans who say they experienced discrimination in a religious setting in the past year, the sample size is too small to determine whether Black Americans who go to certain types of congregations are more likely to have had these experiences in their own congregation or in ones they are visiting.

Protestants (15%), Catholics (16%) and the religiously unaffiliated (15%) are about equally likely to have experienced discrimination in religious settings. However, Black Protestants who attend White or other race churches (21%) are slightly more likely than those who attend Black churches (15%) to have experienced this.

Members of non-Christian faiths are more likely than most other groups to report instances of discrimination in a religious setting in the 12 months prior to the survey (29%). This group is largely Muslim, but also includes Black Americans who are “spiritual but not religious,” and a variety of other faiths. About a quarter of these Black Americans say that people in houses of worship have acted as if they were better than them (22%), while roughly one-in-ten say that people have treated them suspiciously (12%), called them racist names (12%), or left them out of social activities (9%).

Black Americans’ experiences of racial discrimination in religious settings also differ modestly by generation. Those in the oldest generations in the study (Silent Generation and older) are less likely than others to say they have experienced racial discrimination in religious settings (9%). About one-in-five Generation Zers (22%) and Millennials (17%) report that they have experienced this, as do 15% of Generation Xers and 16% of Baby Boomers.

Black Americans are far more likely to say they experienced at least one of the types of discrimination asked about in the survey in nonreligious settings than in religious ones. Nearly half of Black Americans (46%) say that in the past year, people acted as if they were better than them, treated them suspiciously, called them racist names or insulted them, or snubbed them in nonreligious settings.

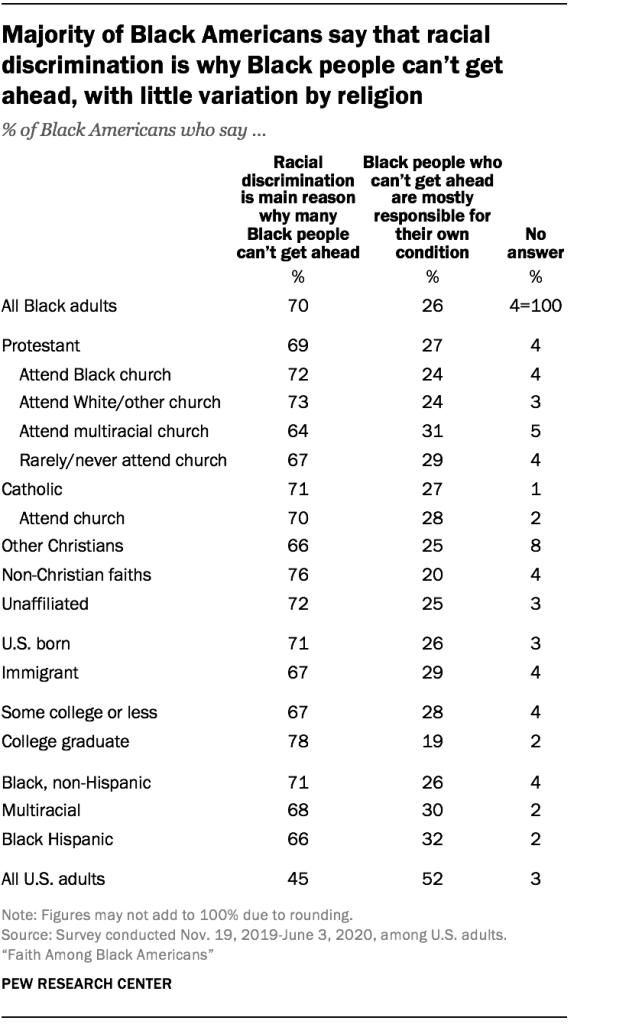

Racial discrimination as a barrier to advancement

The majority of Black Americans (70%) believe that racial discrimination is the main reason that many Black people cannot get ahead in society. About a quarter (26%) say that Black people who cannot get ahead are mostly responsible for their own condition. By contrast, U.S. adults overall are slightly more inclined to say that Black people who can’t get ahead are mostly responsible for their own condition than they are to say that racial discrimination is why Black people can’t get ahead (52% vs. 45%).