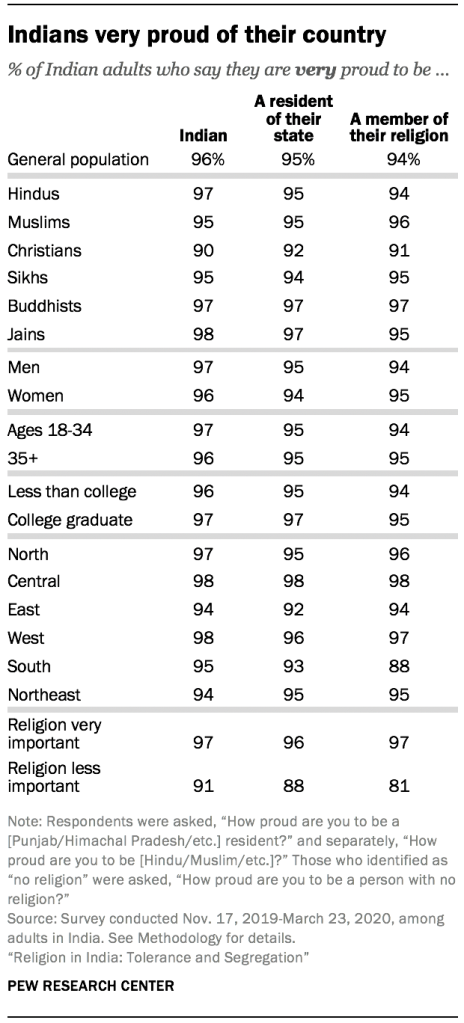

Indians nearly universally take great pride in their country. Fully 96% of Indian adults say they are very proud to be Indian, and similarly large percentages say they are very proud to be from their state and to be a member of their religious community.

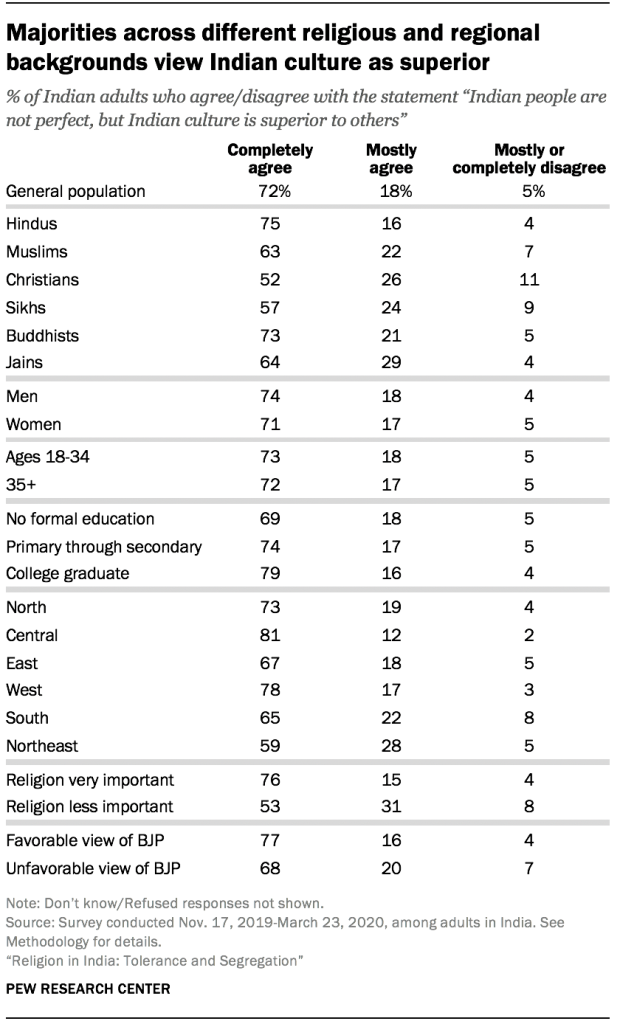

While nearly everyone is proud to be Indian, there is somewhat less consensus on whether Indian culture stands out above all others. A majority of Indians (72%) completely agree with the statement that “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.” But while an especially large share of Indians in the Central region (81%) completely agree that Indian culture is superior, only a slim majority say this in the Northeast (59%).

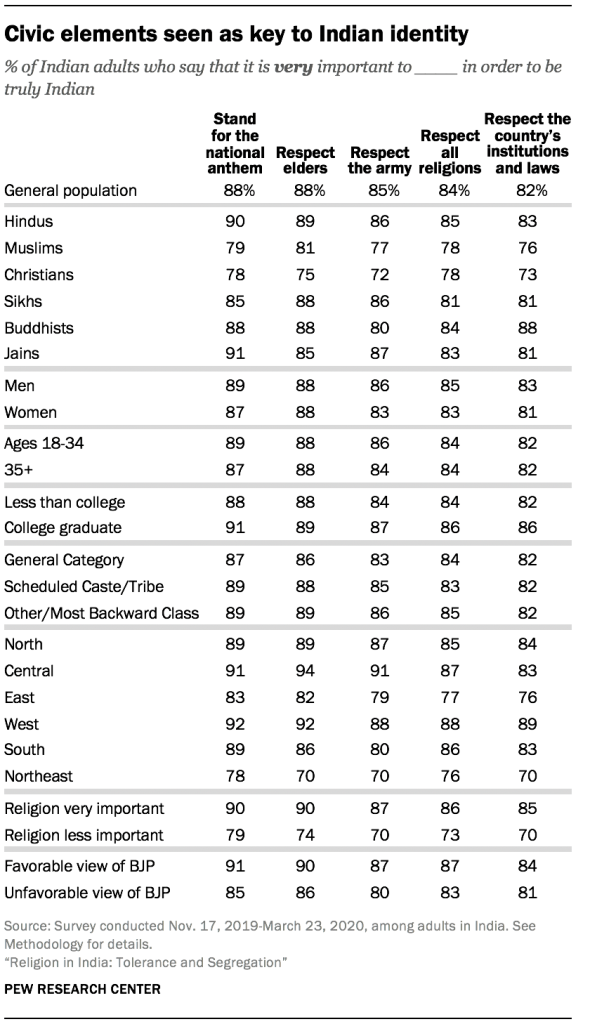

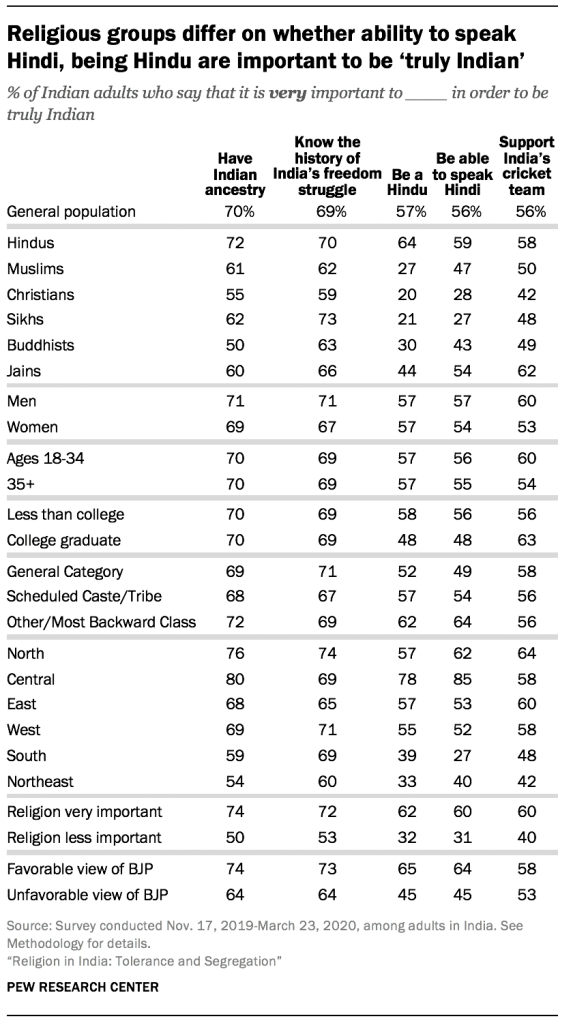

There also are a range of views on what it means to be “truly Indian.” For instance, Indians widely agree that respecting India’s institutions and laws and respecting elders are very important to being truly Indian. But there is less unanimity about whether language and religion are tied up with Indian identity. In a country with 22 official languages and dozens of others, a slim majority (56%) say being able to speak Hindi is very important to being truly Indian. And a similar share of Indian adults (57%), including 64% of Hindus, say being Hindu is very important to being truly Indian.

India’s religious groups and supporters of the country’s different political parties disagree on questions of national identity. While 64% of Hindus say being a Hindu is very important to being truly Indian, far fewer Muslims (27%) stress Hinduism’s importance to being Indian. Politically, Indians with a favorable view of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) are also much more likely than other Indians to say being Hindu is very important to Indian identity (65% vs. 45%). (See “An index of religious segregation in India” in Chapter 3 for additional analysis of the connection between national identity, voting patterns and religious segregation.)

Some attitudes about national identity are closely tied to religious observance. Nearly three-quarters of Indians who say religion is very important in their lives (74%), for example, say that having Indian ancestry is very important to being truly Indian, while only half of those who say religion is less important consider ancestry a central part of national identity.

Although India’s Constitution declares the country a democratic republic – and India is often called the world’s largest democracy – Indians express mixed attitudes when asked whether “a democratic government” or “a leader with a strong hand” would be better suited to solve the country’s problems. Slightly fewer than half of Indians surveyed (46%) indicate a preference for democracy, while a nearly identical share (48%) would prefer a leader with a strong hand. Support for democracy versus a strong leader varies considerably by region. People in the Central part of the country are the least likely to lean toward democracy (33%), while support for a democratic form of government (instead of a leader with a strong hand) is considerably higher in the Northeast (61%), South (53%) and North (51%).

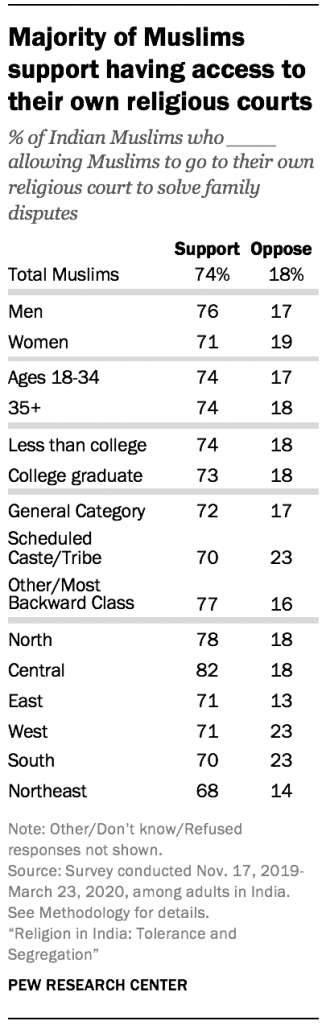

The survey also asked about two policy issues concerning Muslims in India: triple talaq and allowing Muslims to use their own religious courts. Muslims tend to support having their own religious courts (74% in favor), but most oppose Muslim men being allowed to divorce by saying “talaq” three times (56%).

Across India, high levels of pride in country, state and religion

Across the nation, nearly all Indian adults say that they are very proud not only to be Indian, but also to be residents of their respective states. This pattern is consistent across different religions, regions and age groups.

Survey respondents also were asked how proud they are to be a member of their particular religion (e.g., Sikhs were asked how proud they are to be Sikh). Again, roughly nine-in-ten or more among all major religions say they are very proud to be a member of their religious group.

Indians who say religion is very important in their lives are slightly more likely than others to be very proud of their national, state and religious identities, although these views are widespread regardless of how religious people are.

People in the South of the country are somewhat less likely than those in other regions to say they are very proud of their religious identity. For example, among Hindus in the South, 89% say they are very proud to be Hindu, compared with 98% in the Central region. Among Muslims in the South as well, fewer people than elsewhere say they are very proud to be Muslim (88% vs. 96% nationally).

To some extent, Indians’ pride in their religious identities is tied to their views on keeping their own religious community separate from others. Those who say it is important to stop interreligious marriages of men and women are somewhat more likely to say that they are very proud of their religious identity.14 Among Hindus, for example, 97% of those who say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of Hindu women also say they are very proud to be Hindu, compared with 90% among those who don’t see stopping interreligious marriage as a top priority. Muslims show a similar pattern: Those who want to stop Muslims from marrying outside of Islam are more likely to say that they are very proud to be Muslim, although large majorities are very proud to be Muslim regardless of their stance on religious intermarriage.

Large majorities say Indian culture is superior to others

For another perspective on national pride, the survey also asked respondents if they completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the statement “Indian people are not perfect, but Indian culture is superior to others.”

An overwhelming majority of Indians agree with the statement (90%), including 72% who completely agree. Three-quarters of Hindus and roughly the same share of Buddhists (73%) completely agree that Indian culture is superior to others. Among other religious minority groups, somewhat fewer people share this sentiment – about half of Christians (52%) completely agree Indian culture is superior, as do 63% of Muslims and 57% of Sikhs.

Those who say religion is very important in their lives are particularly likely to say Indian culture is superior. Among Hindus, for example, a large majority of those who say religion is very important also completely agree that Indian culture is superior (79%), compared with just over half (54%) of those who consider religion less important in their lives. A similar pattern is seen among Muslims (64% vs. 48%).

Regionally, in the Central part of the country, 81% completely agree that Indian culture is superior, while about six-in-ten in the Northeast (59%) share the sentiment.

As education level increases, so does agreement with the statement. Among college graduates, for example, 79% completely agree that Indian culture is superior to others, compared with 69% of those without a formal education.

Politically, Indians who express a favorable view of the BJP also are more likely than those with an unfavorable view of India’s ruling party to completely agree that Indian culture is superior (77% vs. 68%).

What constitutes ‘true’ Indian identity?

The survey also asked respondents how important a series of items are to being “truly Indian.” This series included both civic measures (respecting the country’s institutions and laws, knowing the history of India’s freedom struggle, supporting the national cricket team, respecting all religions, respecting elders, respecting the army and standing for the national anthem) and more nativist measures (Indian ancestry, speaking Hindi and being a Hindu).15

On the whole, Indians emphasize civic aspects of national identity over nativist ones. For example, while nearly nine-in-ten Indians (88%) say respecting elders is very important to being truly Indian – with little variation by religion, region, caste or age – only a slim majority (56%) say being able to speak Hindi is crucial.

At the same time, even though Indians live in a diverse multireligious and multilingual society, majorities link Indian identity with a particular religion and language, as well as with ancestry. A large majority (70%) say it is important to have Indian ancestry to be truly Indian. And 57% of Indian adults say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian.

While most Hindus (64%) say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, considerably smaller shares of people in other religious communities link the Hindu religion with national identity. Still, 27% of Muslims and 20% of Christians say being Hindu is very important to being truly Indian.

Muslims who have lower levels of education are more likely to say it is important to be Hindu to be truly Indian. This view is also more common among Muslims who are religiously segregated. For example, among those who say all their friends are Muslim, 34% say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, compared with 22% among other Muslims.

Indians in the Central region are the most likely to link Hindu identity with Indian identity (78%), while Indians in the Northeast and South are the least likely to say that being Hindu is very important to being truly Indian (33% and 39%, respectively). Regional patterns also exist among Muslims: 40% of Muslims in the Central region say it is very important to be Hindu to be truly Indian, compared with 17% in the East.

Indians’ views on the importance of speaking Hindi to national identity also vary by region. In regions where more Indians speak Hindi, more people view the language as intrinsic to national identity. Fully 85% of those in the Central region – where more than 99% of respondents list Hindi among the languages they speak – say that speaking Hindi is very important to being truly Indian, while only 27% of those in Southern India (a region where just 14% report speaking Hindi) take the same view.16 This regional pattern is once again true for both Hindus and Muslims.

Adults with lower levels of formal education are somewhat more likely than their college-educated counterparts to link being able to speak Hindi and being Hindu with true Indian identity. Relatedly, members of Other Backward Classes (including a small share of people who volunteered “Most Backward Class”) also are more likely than members of either General Categories or Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes to say speaking Hindi and being Hindu are very important to Indian identity. And Hindus who are more supportive of keeping religious groups segregated from each other – i.e., who support stopping Hindu men and women from marrying non-Hindus – are more likely to express these nativist views of national identity.

When it comes to politics, Hindus who have a favorable view of the BJP are more likely than those with unfavorable views of the ruling party to link being Hindu and speaking Hindi with national identity. For example, a majority of Hindus who have positive views of the BJP (66%) say speaking Hindi is very important to being truly Indian, compared with about half of those who have an unfavorable view of the ruling party (48%).

Half or more among all religious groups surveyed say having Indian ancestry is important to being truly Indian. Still, this attitude is most common among Hindus (72%), especially those who live in the Northern (82%) and Central (81%) parts of the country. Once again, Southern Hindus are less likely than Hindus in most other places to say having Indian ancestry is very important to being truly Indian (59%).

A slim majority of Indian adults (56%) say it is very important to support India’s cricket team to be truly Indian. Majorities of Hindus (58%) and Jains (62%) support this view, but among other religious groups, the share who see a strong link between sports and national identity stands generally lower: Half of Muslims say it is very important to support the country’s cricket team to be truly Indian.

Across all measures, nativist or otherwise, respondents who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to say that all of these aspects are important to being truly Indian. For example, 90% of those who say religion is very important in their lives say it is crucial to respect elders to be truly Indian, compared with 74% among those who consider religion less important in their lives.

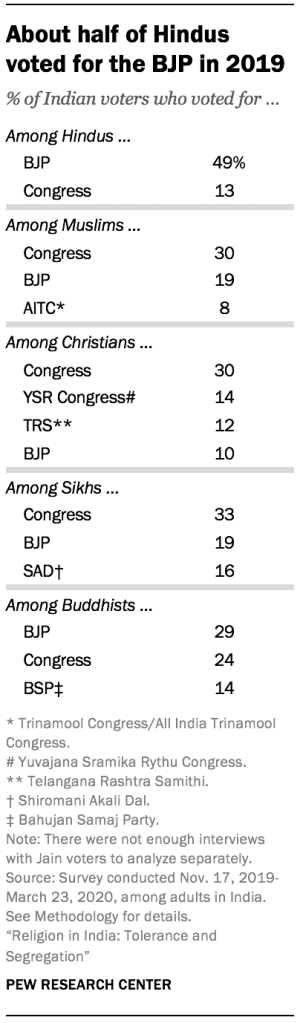

Large gaps between religious groups in 2019 election voting patterns

In the spring of 2019, India held a national election for its lower house of Parliament, the Lok Sabha. About two-thirds (67%) of the eligible population voted in the election, ultimately giving the BJP a majority of seats in the Lok Sabha.

This survey asked respondents whom they voted for in 2019. While a plurality (44%) say they voted for the winning party, responses vary significantly by religious group. Nearly half of Hindu voters (49%) say they voted for the BJP, compared with significantly fewer people among minority religious groups with a large enough sample size of voters to analyze.

Indeed, the survey indicates that Indian National Congress (INC) – one of the main opposition parties to the BJP – was the top choice among Muslim (30%), Christian (30%) and Sikh (33%) voters in 2019. Buddhist voters were more evenly split, with 29% supporting the BJP and 24% supporting Congress. While the survey did not include enough Jain voters to report how they voted in this election, Jains appear to strongly embrace India’s ruling party: In response to a separate question, fully 70% of Jains say they feel closest to the BJP, regardless of whether they voted in the last election.

One-in-five Muslims (19%) did vote for the BJP, despite the party sometimes being described as promoting a Hindu nationalist agenda in its policies.17 Muslim voters who supported the BJP in the last election differ in multiple ways from those who did not. For example, Muslims without a college degree are more likely than college graduates to say they voted for the BJP, while the opposite pattern is true for Muslims who voted for the INC. Religious observance is also a significant factor: Muslim voters who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to have voted for the BJP than voters who say religion is less important (19% vs. 12%). Regionally, about four-in-ten Muslim voters in the Northeast (39%) say they voted BJP, compared with one-quarter or fewer in all other regions.

India has a multiparty system. According to official statistics, there are seven national parties, more than 50 state or regional parties, and over 2,000 other unlisted political parties. Many voters in minority religions opted to vote for parties other than the BJP or Congress, the two largest national parties. For example, fully 14% of Buddhists say they voted for the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), a national party focused primarily on the welfare of lower castes and minority religions (89% of Buddhists are members of Scheduled Castes). Support for regional parties also is tied to religion. For example, 16% of Sikhs say they voted for Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) in 2019. SAD is a regional party representing Punjabi interests; according to the census, 77% of India’s Sikhs live in Punjab.

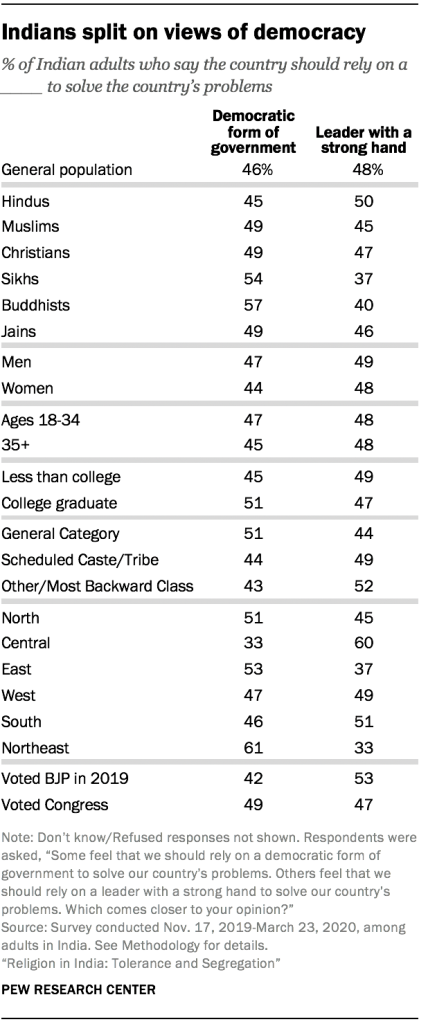

No consensus on whether democracy or strong leader best suited to lead India

Despite decades of elections and being lauded as the world’s most populous democratic republic, support for democracy (as opposed to a more authoritarian form of government) is far from unanimous in India.

The survey asked which would be better suited to solve the country’s problems: a “democratic form of government” or a “leader with a strong hand.” Of course, it is possible for a leader who rules with a strong hand to be democratically elected, but by forcing a choice between these two options, the question sought to capture respondents’ preferences for what type of government is best, on balance.

Slightly fewer than half of Indians say that the country should rely on a democratic form of government to solve the country’s problems (46%). The other half say that it would be better for the country to have a leader with a strong hand (48%).

Pew Research Center’s survey is not the only one that finds ambivalence among Indians about the efficacy of democracy. A 2019 survey conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) asked Indian adults whether they agree or disagree that “The country should be governed by a strong leader who does not have to bother about winning elections.” Roughly six-in-ten Indians agreed with the statement. (See “What other surveys on religion, democracy and pluralism in India show” below for a discussion of this and other CSDS findings.)

This ambivalence toward democracy exists to some degree among all the country’s religious groups. In the Pew Research Center survey, among Hindus, Muslims, Christians and Jains, there is no clear majority position on this question. Only among Buddhists (57%) and Sikhs (54%) do more than half of adults express a preference for a democratic form of government.

Regional differences are more stark. Fully six-in-ten Indians in the Central region say that a leader with a strong hand is best suited to solving India’s problems, compared with only one-third who prefer a democratic form of government. The opposite is true in the Northeast, where about six-in-ten adults prefer democracy (61%). There also is a modest gap between urban and rural regions, with half of urban residents (50%) preferring democracy, compared with 44% of adults in rural districts.

Indian adults with a college degree are more likely than those with less education to prefer a democratic form of government (51% vs. 45%). And Indians who belong to General Category castes (51%) are more likely than those who belong to Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (44%) or Other Backward Classes (43%) to favor democracy.

The 2019 Indian general election included more voters than any other election in human history. Despite this level of democratic participation, roughly half of those who report that they voted in the election say they would prefer a leader with a strong hand (48%) over a democratic form of government (46%). BJP voters are slightly more likely than those who voted for the opposition Indian National Congress party to say they see a leader with a strong hand as more suited to solve the country’s problems (53% vs. 47%).

Sidebar: What other surveys on religion, democracy and pluralism in India show

While this study is the first large-scale, nationally representative survey of India performed by Pew Research Center, other surveys in India have asked similar questions. One of the largest is the National Election Study conducted by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) through its research wing, Lokniti. This survey has been conducted alongside every Lok Sabha election since 1996, and the most recent round included about 24,000 respondents in the post-election poll. Due to differences in question wording and sampling, data from Pew Research Center’s survey and that of CSDS should not be directly compared. But looking at the CSDS studies in conjunction with Pew Research Center’s survey shows broadly similar findings on issues around religion and nationalism.

High levels of support for religious pluralism

Previous work conducted by CSDS shows that support for religious pluralism has remained high over time. In 2009, more than 80% of Indians agreed with the statement “Citizens of India should promote harmonious relationship between all religions.” The 2019 National Election Study by CSDS also demonstrates a high level of support for religious pluralism. Roughly three-quarters of Indians in the CSDS study (76%) say that “India belongs to citizens of all religions equally, not just Hindus,” while just 15% say “India primarily belongs to only Hindus.” Meanwhile, 2019 Pew Research Center data shows that 84% of Indians believe respecting all religions is very important to being truly Indian. (See “What constitutes ‘true’ Indian identity?” above for more details.)

Declining support for democracy

The CSDS National Election Studies show that, over time, Indians have become less supportive of democracy. In 2009, about four-in-ten Indians agreed with the statement “The country should be governed by a strong leader who does not have to bother about winning elections.” A decade later, more than six-in-ten Indians say they would prefer a strong leader who does not have to worry about elections.

Strong preference for religious segregation

In addition to the National Election Study, CSDS, in collaboration with Azim Premji University, measured public opinion around communal relations in 2018. The survey interviewed roughly 24,000 Indians from 12 states, and the findings highlight a preference for public policies that maintain the separation of religious groups: Hindus and Sikhs in the states surveyed say people who engage in religious conversion should be punished by the government. Members of other minority religions are less supportive than Hindus and Sikhs of policies that would punish proselytizing. Similarly, Pew Research Center’s survey shows an inclination for religious segregation; for example, roughly two-thirds of Indians say it is very important to stop men and women in their religious community from marrying into another religion. (See Chapter 3 for more details.)

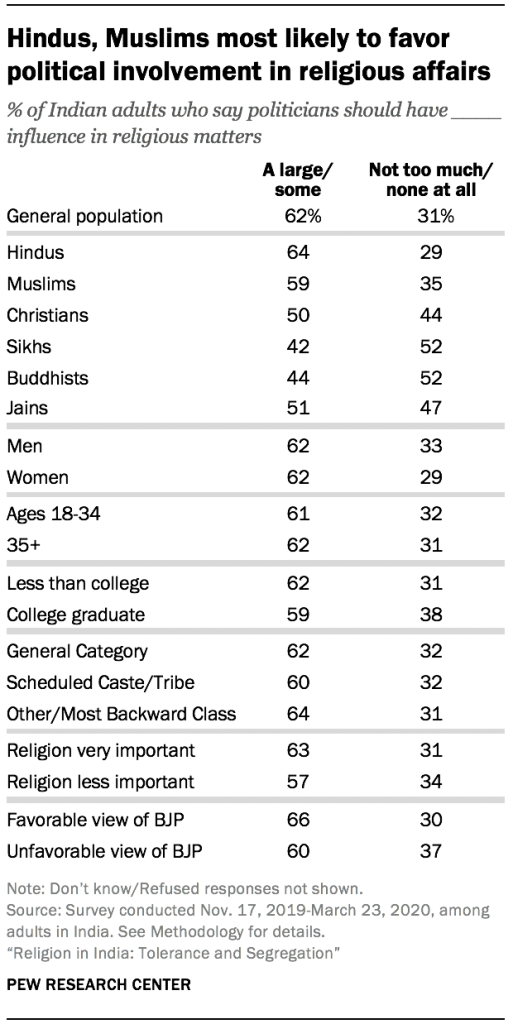

Majorities support politicians being involved in religious matters

A majority of Indians say that politicians should have at least “some” influence in religious matters (62%), including roughly three-in-ten (29%) who say politicians should have “a large” influence. Meanwhile, 31% of all Indian adults say politicians should generally stay out of religious affairs, including 17% who think politicians should have no influence at all.

Majorities of both Hindus (64%) and Muslims (59%) – India’s two largest religious groups – say politicians should have at least some influence in religious matters, while on balance, Sikhs and Buddhists tend to prefer little or no political influence in religious affairs.

Generally, men and women, Indians of different age groups and those living in different parts of the country lean toward the position that politicians should have at least some influence in religious matters. Indians who have a favorable view of the BJP are slightly more likely than other Indians to say politicians should have some or a large influence in religious matters (66% vs. 60%).

Among Hindus, those who say religion is very important in their lives are somewhat more likely than other Hindus to say that politicians should have at least some influence in religious matters (65% vs. 59%).

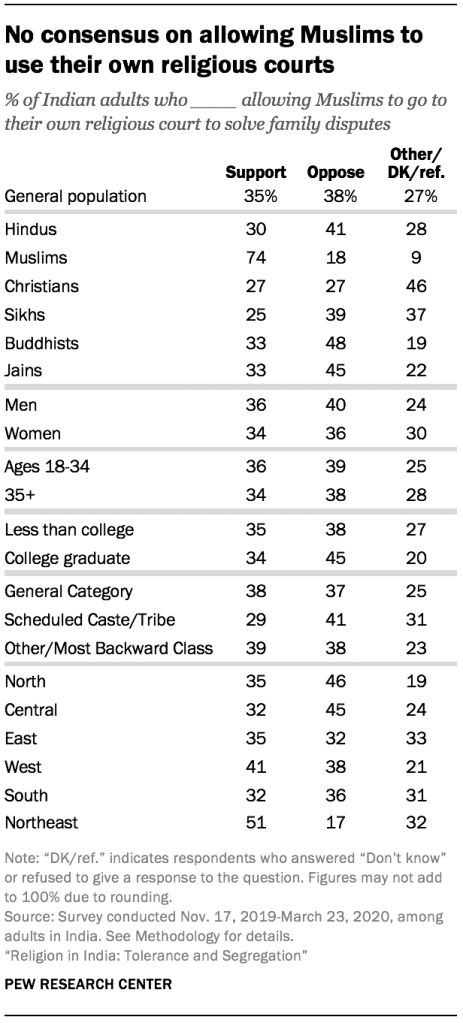

Indian Muslims favor their own religious courts; other religious groups less supportive

Alongside the civil court system, Muslims in India have the option of settling family disputes such as inheritance issues in courts that follow Islamic legal principles (for more information, see “Islamic courts in India” in the report overview). But whether or not Muslims should be allowed to go to their own religious courts remains a hotly debated topic.

Indians on the whole express mixed opinions on this issue, with similar proportions of the public supporting (35%) and opposing (38%) the use of these courts. Roughly a quarter of Indians (27%) do not take a position, perhaps reflecting the low salience of this issue for many people.

However, a clear majority of Muslims (74%) say they should be allowed to have their own courts to resolve family and property disputes. Hindus, on the other hand, are more likely to oppose (41%) rather than support (30%) religious courts for Muslims; the same pattern holds among Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains, although substantial shares of all non-Muslim groups do not express an opinion on this subject.

There is far less opposition to Islamic courts in Northeastern India than in any other region.

Muslims across different regions, castes and educational backgrounds consistently support religious courts for their group. Muslim men (76%) are slightly more likely than Muslim women (71%) to support religious courts.

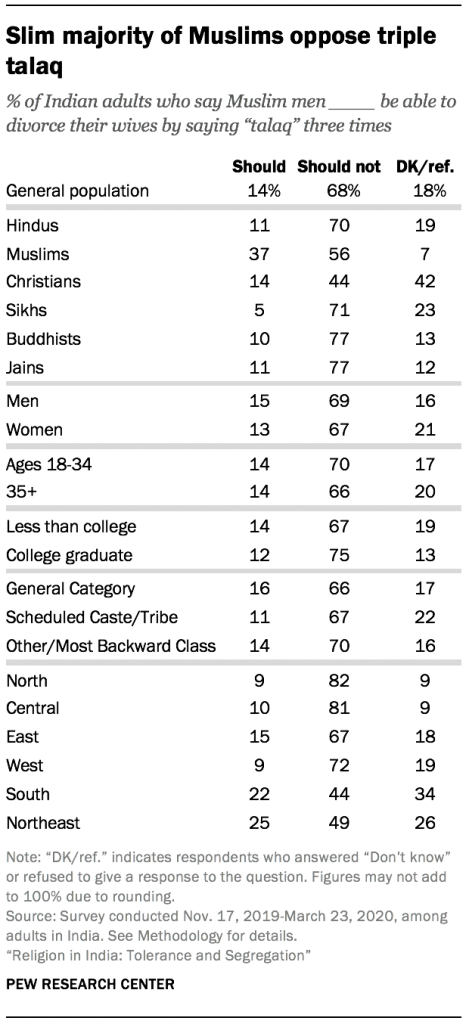

Most Indians do not support allowing triple talaq for Muslims

For the first seven decades after Indian independence, it was legal for Muslim men to instantly divorce their wives by saying “talaq” (“divorce” in Urdu and Arabic) three times – commonly referred to as “triple talaq” (for more information, see “Islamic courts in India” in the report overview). The Supreme Court ruled triple talaq unconstitutional in 2017, and in 2019, after much public debate, India’s Parliament passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights of Marriage) Bill, which banned the practice.

A clear majority of Indians as a whole (68%) – including seven-in-ten or more Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains – say that Muslim men should not be allowed to divorce their wives using triple talaq. Just 14% say triple talaq should be allowed, while 18% do not answer the question, perhaps reflecting some unfamiliarity with the practice – especially among Christians.

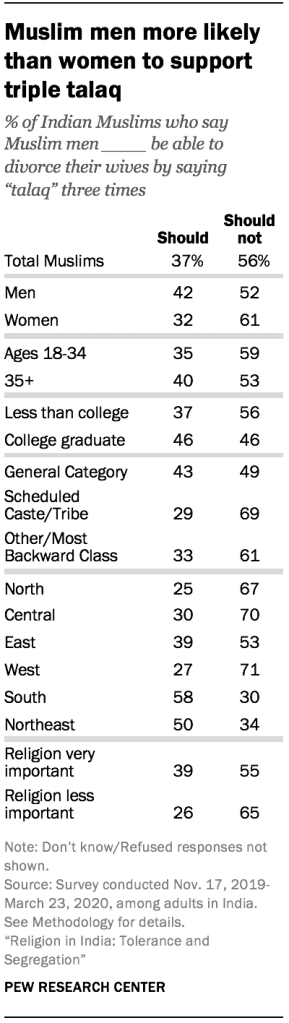

Among Muslims, too, a majority (56%) oppose allowing Muslim men to divorce their wives by saying “talaq” three times. Still, 37% of Muslims favor the practice, which is considerably higher than in any other religious group surveyed.

Muslim opinions of triple talaq differ based on several factors. For example, Muslim men are more likely than women to approve of the practice (42% vs. 32%). And Muslims in General Category castes (43%) are more likely than members of Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (29%) and Other Backward Classes (33%) to say triple talaq should be allowed. Relatedly, Muslims with college degrees also are more supportive of triple talaq than are Muslims with less education (46% vs. 37%).

Religious observance also plays a significant role. Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to support triple talaq than those who say religion is less important (39% vs. 26%). And Muslim men who attend religious services at least once a week also are more likely than other men to support the practice (44% vs. 27%).

Muslims in the South (58%) and Northeast (50%) are more likely than those in other regions of India to say Muslim men should be allowed to divorce their wives by triple talaq. Conversely, at least two-thirds of Muslims in the Western (71%), Central (70%) and Northern (67%) regions of the country do not support the practice.