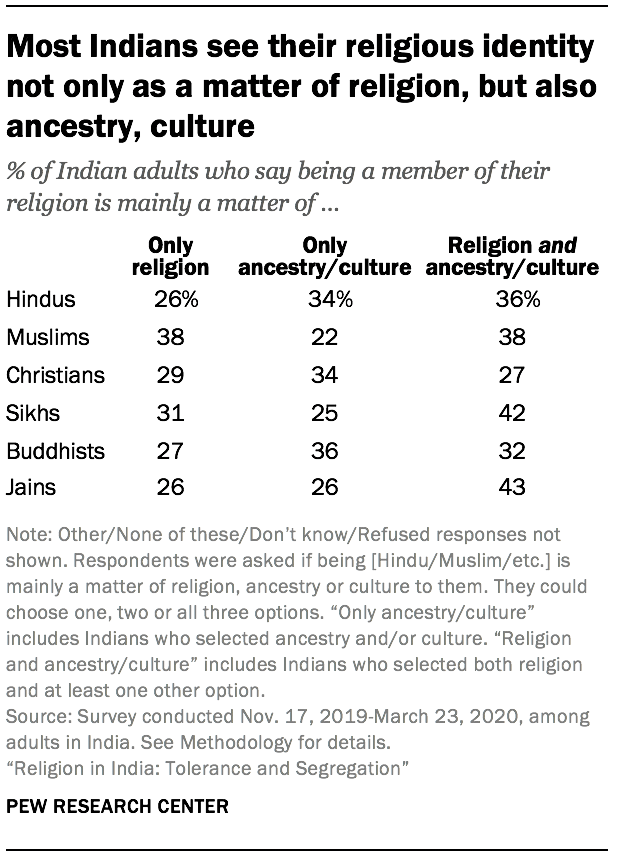

The vast majority of Indians identify with six major religious groups: Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains. In this report, respondents are often categorized accordingly, based on their answers to a question about their religious identity. But the survey also finds that for most members of these six groups, these identities are not only about religion.

Indeed, Indians are split over whether being a member of their religious group (e.g., being Sikh or being Muslim) is mainly a matter of religion, mainly a matter of culture or ancestry, or some combination of religion and culture/ancestry. There is no clear consensus on this in any of the six religious groups. Among Hindus in India, for example, there is no single understanding of what it means to be a Hindu.

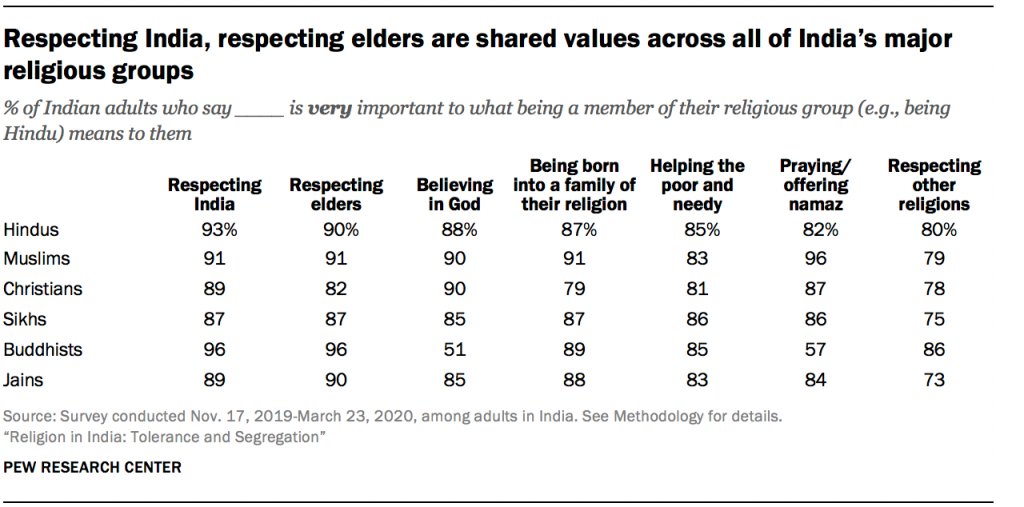

On the other hand, there is substantial agreement on some beliefs, practices and attributes that are very important to Indians’ religious identities. For instance, overwhelming shares across groups see both secular behaviors – such as respecting elders, helping the poor and needy, and respecting India – and more overtly religious attributes, such as believing in God and praying, as crucial to what being a member of their group means to them. Indian Buddhists are the lone exception on some of these measures, with far fewer saying belief in God and prayer are central to being Buddhist.

The survey also approached the concept of religious identity and belonging from the other direction: In addition to what is very important to being Christian or Jain, for example, what is disqualifying for members of each group? A strong majority of followers say that people who do not abide by dietary restrictions prohibiting the consumption of beef (for Hindus, Sikhs and Jains) or pork (for Muslims) cannot be members of their community. But when it comes to whether a person can claim their religious identity even if they do not engage in the traditional religious practices of communal worship or prayer, there is less agreement.

The remainder of this chapter looks at these questions in greater detail. It also examines Indians’ identification with subgroups or sects within each of the six major religions, as well as with Sufism.

Most Indians say being a member of their religious group is not only about religion

Nearly all Indian adults identify with a religious group, but for most of them – regardless of which group they are a part of – this identity is not just about religion.

Respondents were asked whether being a member of their religious group (e.g., being Hindu, Christian or Sikh) is mainly a matter of religion, ancestry or culture – or some combination of the three.

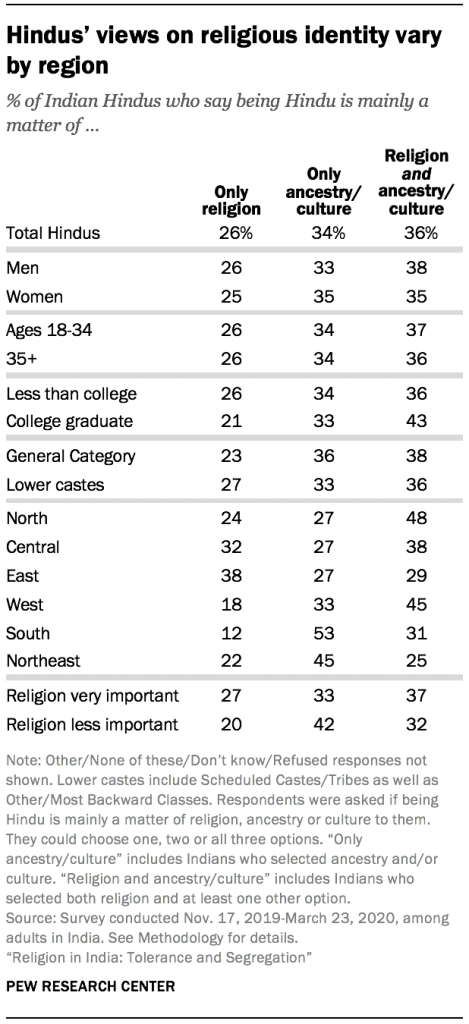

Overall, only around a quarter of Indian Hindus (26%) say being Hindu is only a matter of religion. A somewhat greater share (34%) believe it is solely a matter of ancestry and/or culture, and a similar portion (36%) believe Hinduism is a matter of religion and ancestry/culture.

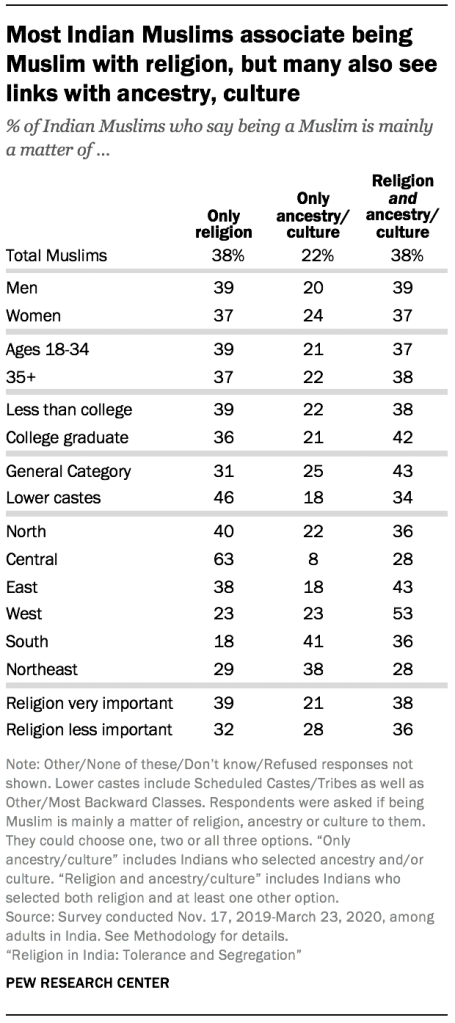

Muslims in India are more likely than Hindus to say their identity is only a matter of religion (38%) and less likely to view being Muslim exclusively as a matter of ancestry and/or culture (22%). Like Hindus, however, many say being Muslim is a combination of these things (38%).

Overall, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains are split on this question, with no more than about three-in-ten in any of these groups linking their identity solely with religion. For instance, among Jains, 26% say being Jain is only about religion; an identical share say it is only about ancestry and/or culture, and a plurality (43%) say it is some mixture of religion and ancestry/culture.

Among Indian Hindus, there are regional differences in views toward Hindu identity. Hindus in the South (12%) are less likely than others to say being Hindu is exclusively a matter of religion, while those in Eastern (38%) and Central (32%) India are most likely to link Hinduism solely with religion.

Still, across all regions, most Hindus say that to them, being Hindu is wrapped up with ancestry and/or culture in addition to (or instead of) religion. And in the South, roughly half (53%) say being Hindu is only a matter of ancestry and/or culture – and not mainly a matter of religion.

Overall, Hindus with higher religious commitment are slightly more likely to connect their religious identity exclusively with religion. Hindus who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than others to say that being Hindu is a matter only of religion (27% vs. 20%).

Indian Muslims also express differing views on what it means to be Muslim depending on where they live. A majority of Muslims in the Central region (63%) say that to them, being Muslim is a matter only of religion, while significantly smaller shares of Muslims express this view in the rest of the country. In Southern India, for example, just 18% say being Muslim is a matter of religion alone, while the vast majority say their Muslim identity is tied up with ancestry and/or culture.

Muslims in lower castes are more likely to associate Muslim identity only with religion.

Common ground across major religious groups on what is essential to religious identity

The survey asked Indian adults how important each of seven attributes or behaviors is to their religious identity. Overall, Indians across all major religions generally say these seven traits are very important to what it means to them to be Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain.

For example, roughly eight-in-ten or more in all six groups say respecting elders, respecting India, helping the poor and needy, and being born into a family of their religion (e.g., being born into a Muslim family or being born into a Christian family) are all very important to their religious identity. And about seven-in-ten or more say respecting other religions is crucial to being a member of their own religious group, whether they are Hindu (80%), Muslim (79%) or something else.

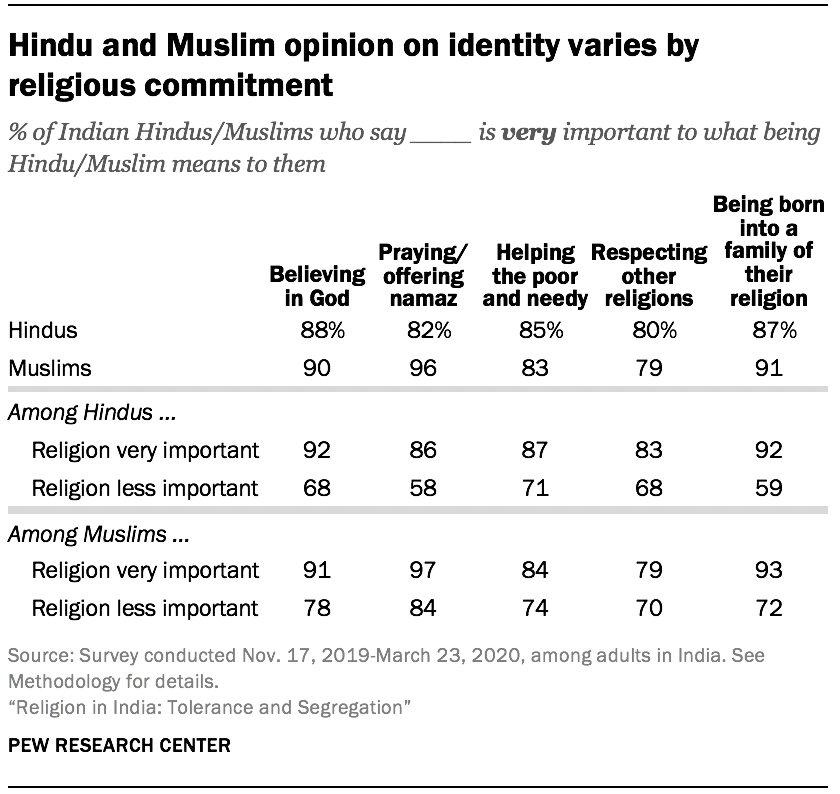

Indeed, India’s two largest religious groups look very similar on most of these questions: Hindus and Muslims agree that believing in God (88% and 90%, respectively), helping the poor and needy (85% and 83%) and respecting India (93% and 91%) are very important to their religious identity. The largest difference emerges in the groups’ views on praying or offering namaz; Muslims are more likely than Hindus to say prayer is very important to being a member of their group (96% vs. 82%), although overwhelming shares of both religious groups view prayer as important.

Buddhists in India stand out as much less likely to tie prayer – and also belief in God – to their Buddhist identity, reflecting the relatively low importance of these beliefs and practices in the Buddhist religion. While about eight-in-ten or more in each of India’s other major religious groups say believing in God and praying are very important to what it means to be a member of their religious group, far fewer Buddhists (51%) say believing in God is crucial to what being Buddhist means to them, and 57% say the same about praying.

These large differences between Buddhists and members of other religions do not exist across other behaviors or traits. If anything, Buddhists are slightly more likely than other groups to say that respecting elders, respecting India and respecting other religions are very important to being Buddhist.

Among Hindus and Muslims, there are large differences on some of these questions based on differing levels of religious commitment. Generally, Hindu and Muslim adults who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than other adults to say these seven traits are very important to their religious identity. For example, strongly committed Muslims are more likely than other Muslims to say believing in God is very important to being Muslim (91% vs. 78%). And while 92% of highly religious Hindus say being born into a Hindu family is crucial to what being Hindu means to them, fewer Hindus who are less religious (59%) feel the same way.

Hindu and Muslim attitudes on these questions generally do not differ very much by demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education or caste.

India’s religious groups vary on what disqualifies someone from their religion

In addition to asking what is important to their religious identity, the survey also asked Indians what would disqualify someone from being a member of their religious community.

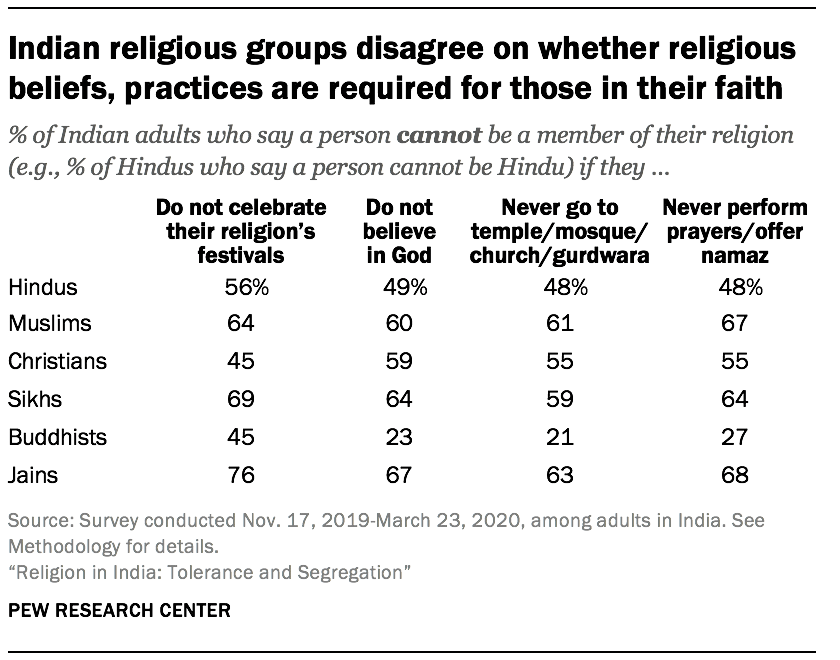

There is a range of opinions across India’s religious groups over whether someone can be a member of their religion if they do not partake in certain religious beliefs and practices. For example, about two-thirds of Jains (68%), Muslims (67%) and Sikhs (64%) say a person who never prays cannot be a member of their religious community. Meanwhile, a slim majority of Christians (55%), about half of Hindus (48%) and roughly a quarter of Buddhists (27%) say never praying would disqualify a person from their religion. Patterns are broadly similar when it comes to whether a person who does not believe in God, never goes to their house of worship or does not celebrate their religion’s festivals can be a member of each community.

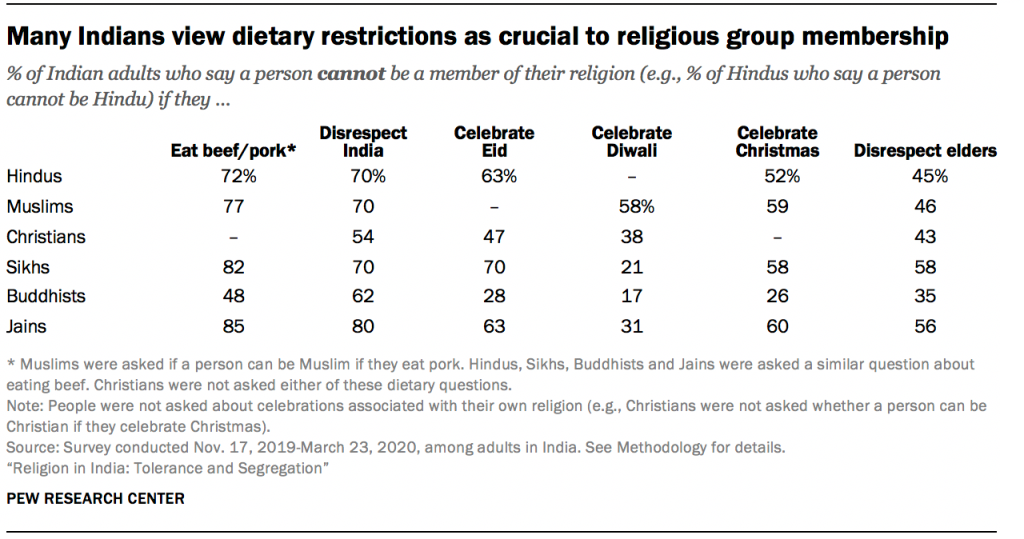

Within several religious groups, followers are more united in disapproval of behaviors that violate their religions’ dietary laws or traditions. Most Hindus (72%), Sikhs (82%) and Jains (85%) say a person who eats beef cannot be a member of their group, while a similarly large majority of Muslims (77%) say a person cannot be Muslim if they eat pork.

Many Indians also say that celebrating holidays associated with other religions is disqualifying. For example, 63% of Hindus and Jains say a person cannot be a member of their group if that person celebrates the Islamic festival of Eid, and 70% of Sikhs view Eid celebrations as incompatible with Sikhism. About six-in-ten Muslims say a person cannot be Muslim if they celebrate Christmas (59%) or Diwali (58%). On the other hand, relatively few Sikhs (21%) and Buddhists (17%) view Diwali celebrations as disqualifying someone from their group.

Across many of these items, Buddhists again prove an exception. They are generally the most willing to accept someone as a fellow Buddhist under a variety of circumstances. For instance, a majority of Buddhists say a person can be Buddhist if they do not believe in God, do not pray and do not go to a temple, and that it’s also acceptable to celebrate the festivals of other religions. “Disrespecting India” is the only attribute mentioned in the survey that a majority of Buddhists (62%) see as incompatible with Buddhism. Roughly seven-in-ten Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs and eight-in-ten Jains also say that someone who disrespects India cannot be a member of their faiths.

While large majorities of all six major religious groups in India view respecting elders as very important to their religious identity (see “Common ground across major religious groups on what is essential to religious identity” above), smaller shares say a person who disrespects elders should be excluded from their group.

Hindus say eating beef, disrespecting India, celebrating Eid incompatible with being Hindu

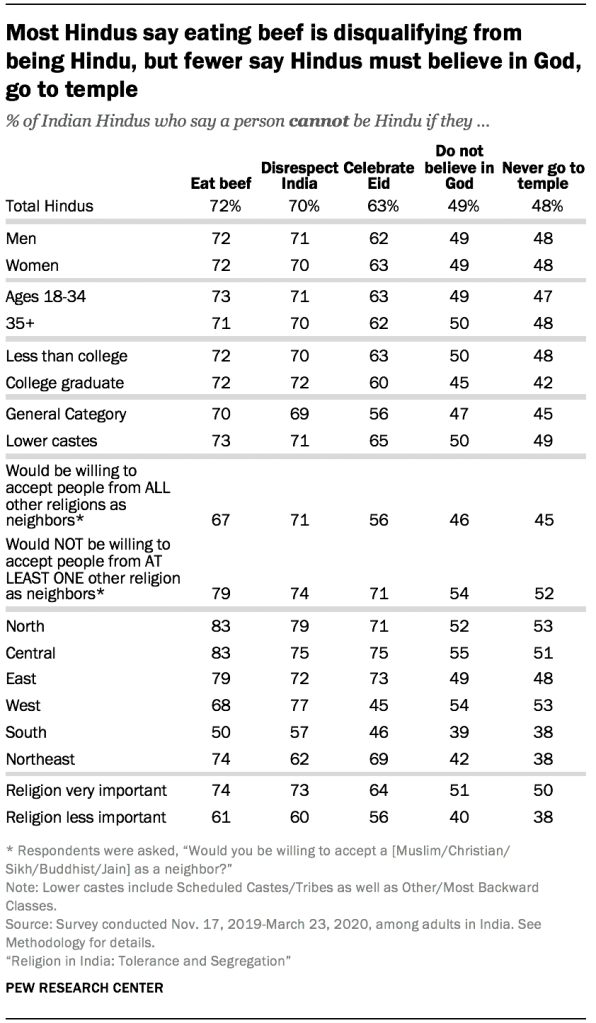

While Hindus are roughly split over whether a person can be Hindu if they do not believe in God, never go to temple or never pray, there is more consensus that eating beef, disrespecting India or celebrating Eid disqualify someone from being Hindu.

There are wide regional differences among Hindus when it comes to views toward certain behaviors and their links with Hindu identity. For instance, Hindus in the West and South are less likely than those elsewhere to view eating beef or celebrating Eid as incompatible with being Hindu.

Differences also arise around religious commitment. Hindus who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely than other Hindus to say several of these behaviors are disqualifying.

Further, Hindus who are willing to accept followers of all other religions in their neighborhoods are less likely than others to say some of these behaviors disqualify a person from being a Hindu.

For instance, among Hindus who are willing to accept neighbors of all other major religions, 67% say a person cannot be Hindu if they eat beef, compared with 79% who say this among Hindus who are unwilling to accept a neighbor from at least one other religious group.

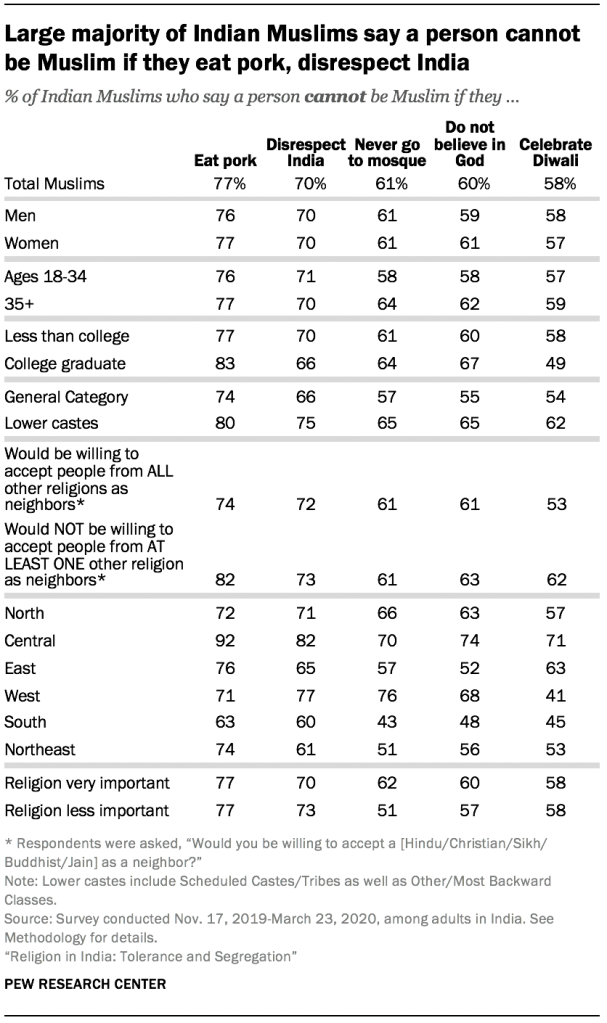

Muslims place stronger emphasis than Hindus on religious practices for identity

Muslims are generally more adamant than Hindus about the importance of religious belief and practice to Muslim identity. Most Muslims say a person cannot be Muslim if they do not believe in God (60%), never offer namaz (67%) or never go to mosque (61%). Yet they agree with Hindus on the importance of observing dietary restrictions and celebrating festivals to religious identity: Fully three-quarters of Muslims (77%) say someone who eats pork cannot be considered a Muslim, while about six-in-ten feel the same way about those who celebrate Diwali or Christmas.

Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives and those who say it is less important are equally likely to say eating pork is disqualifying in their religion (77% each). On the other hand, highly committed Muslims are more likely than others to say that someone who never goes to mosque cannot be Muslim (62% vs. 51%). There also are some variations on these questions by region: For instance, Muslims in Central India are especially inclined to say a person who eats pork cannot be Muslim (92%).

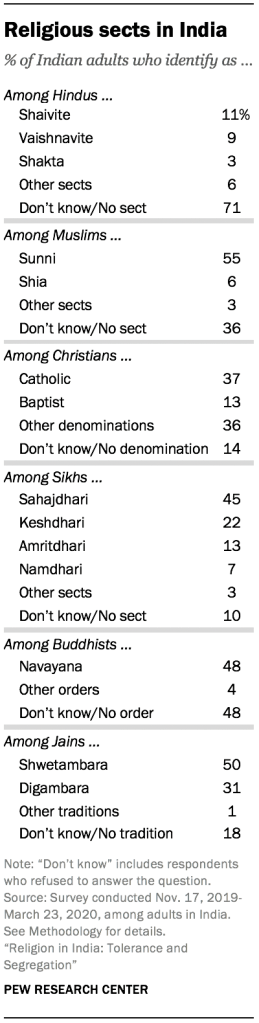

Many Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists do not identify with a sect

The survey also asked respondents if they identify with a particular sect or denomination within their religion. For example, Hindus were asked if they identify as Vaishnavite, Shaivite, Shakta, some other sect or no sect in particular. The vast majority of Hindus say they either don’t know their sect (51%) or that they don’t identify with any sect (20%). The survey finds low levels of sect identity both among Hindus who say religion is very important in their lives and among those who consider religion less important, indicating the generally low salience of these sects to Hindus’ religious lives today.

Sect identity is more common among other religious groups in India. For example, the predominant sect among Indian Muslims is Sunni Islam (55%), while 6% of Indian Muslims identify as Shia. Still, roughly a third of Indian Muslims say either that they have no sect (14%) or they don’t know their Muslim sect (22%). Indeed, previous Pew Research Center surveys have found that substantial shares of Muslims in many countries do not provide a specific sect identity.

Many Buddhists in India also do not identify with a Buddhist order, saying instead they don’t know their order (35%) or have “no order in particular” (13%). Most of the remainder identify with the Navayana Buddhist order: Roughly half of Indian Buddhists (48%) are Navayana, or “new vehicle,” Buddhists. Navayana is a Buddhist order native to India and inspired by the writings of one of India’s founding fathers, B.R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar was born a Hindu Dalit (the lowest rung of the socioeconomic hierarchy) and later converted to Buddhism. Today, nearly all of India’s Buddhists belong to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes or other lower classes (see Chapter 4).

Most Sikhs, Christians and Jains in India identify with particular sects, denominations or traditions. Among Christians, Catholicism is the predominant denomination (37%), but many Protestant denominations, including Baptists (13%), have a presence in India as well.

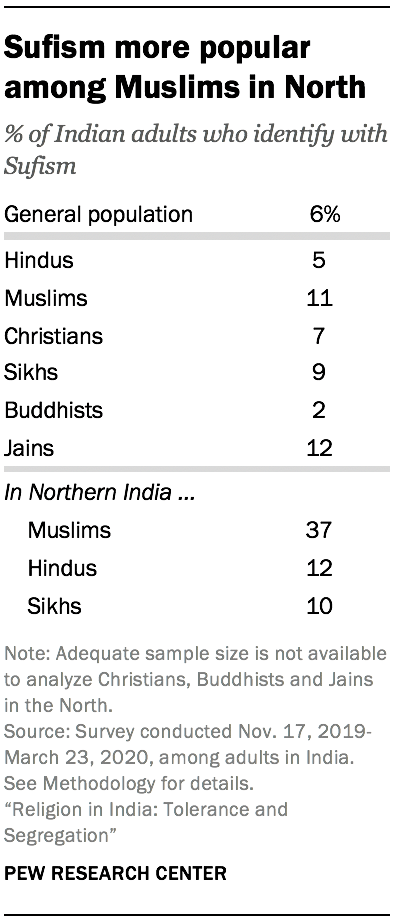

Sufism has at least some followers in every major Indian religious group

Nationally, relatively few Indians (6%) identify as Sufi, a mystical branch of Islam. But the survey makes clear that for many people, Sufi identity exists alongside another religious identity, and Sufi orders have at least some presence among members of every major religious group in India. For instance, 5% of Hindus, 11% of Muslims and 9% of Sikhs surveyed identify with Sufism, which came to India many centuries ago and subsequently incorporated elements of Hinduism.13

Sufis emphasize a connection with God through saints, often referred to as pirs. Sufi orders tend to follow a specific Sufi pir – for example, the Chistiyya Sufi order follows the ascetic, poet and philosopher Moinuddin Chishty, while the Qadriyya order is based on the writings and poetry of Abdul Qadir Gilani. Today, Indians of different religious backgrounds visit the tombs of Sufi pirs to offer their respects, and Sufi poetry and music play a role not only in religious life but also in Indian popular culture.

Overall, Sufism is more popular in Northern India, where the movement has deep historical roots, than in other parts of the country. Among Muslims in the North (Chandigarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Punjab and Rajasthan), 37% identify as Sufi, including 7% who identify with the Chistiyya order and 12% who identity with the Qadriyya order. Among Hindus in the North, 12% identify as Sufi (including 6% with the Chistiyya order), as do 10% of Sikhs in the region.