Key Findings From the Global Religious Futures Project

The Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project seeks to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Since 2006, it has included three main lines of research:

- Surveys in more than 95 countries (and 130 languages) asking nearly 200,000 people about their religious identities, beliefs and practices

- Demographic studies that use censuses and other data sources to estimate the size of religious groups, project how fast they are growing or shrinking, and analyze mechanisms of religious change

- Annual tracking of restrictions on religion in 198 countries and territories

Pew Research Center – a nonprofit, nonpartisan fact tank – conducts these studies and makes them freely available to the public. The Center does not promote any religious or spiritual beliefs (or nonbelief).

The Global Religious Futures (GRF) project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and The John Templeton Foundation. Here are some big-picture findings from the GRF, together with context from other Pew Research Center studies.

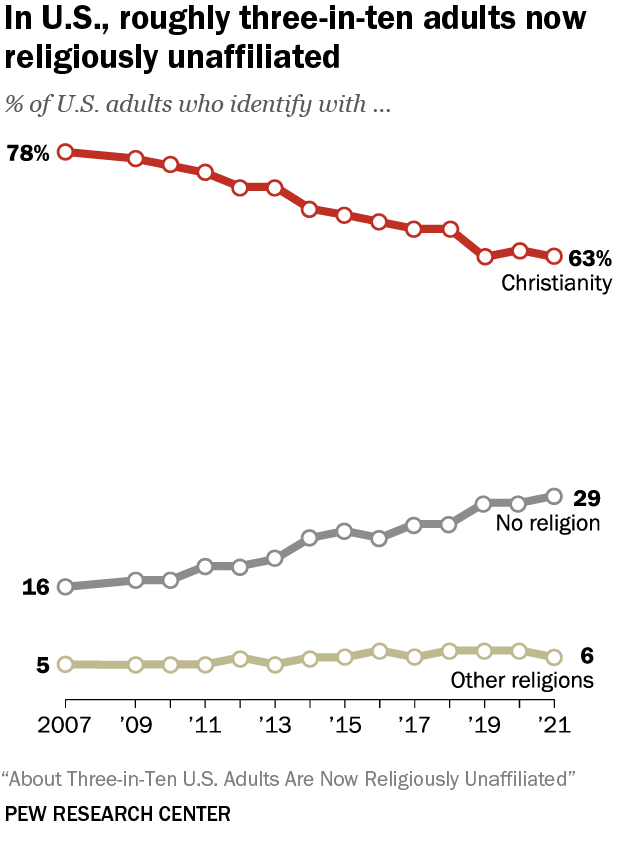

People are becoming less religious in the U.S. and many other countries

The U.S. public seems to be growing less religious, at least by conventional measures. The percentage of American adults who identify as Christian has been declining each year, while the share who do not identify with any religion has been rising rapidly. (Members of non-Christian religions, such as Judaism, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, to name just a few, make up a smaller share of Americans.)

This pattern began a few decades ago, and it is projected to continue into the foreseeable future. Moreover, affiliation – whether people say they belong to a religion – is not the only indicator that is dropping. Religious observance also has fallen in surveys asking U.S. adults how often they attend religious services, how frequently they pray, and how important they consider religion to be in their lives.

The United States is far from alone in this way. Western Europeans are generally less religious than Americans, having started along a similar path a few decades earlier. And the same secularizing trends are found in other economically advanced countries, as indicated by recent census data from Australia and New Zealand.

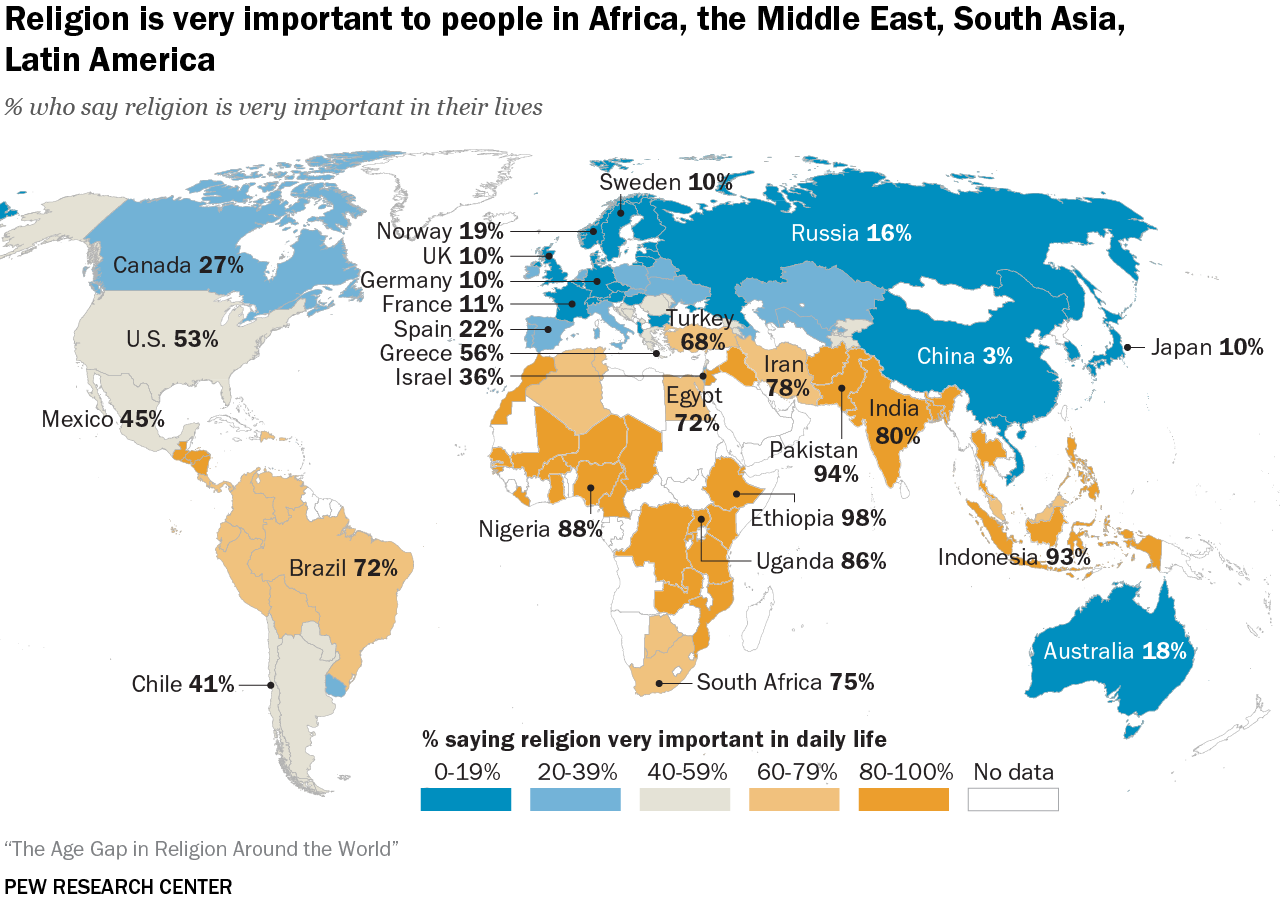

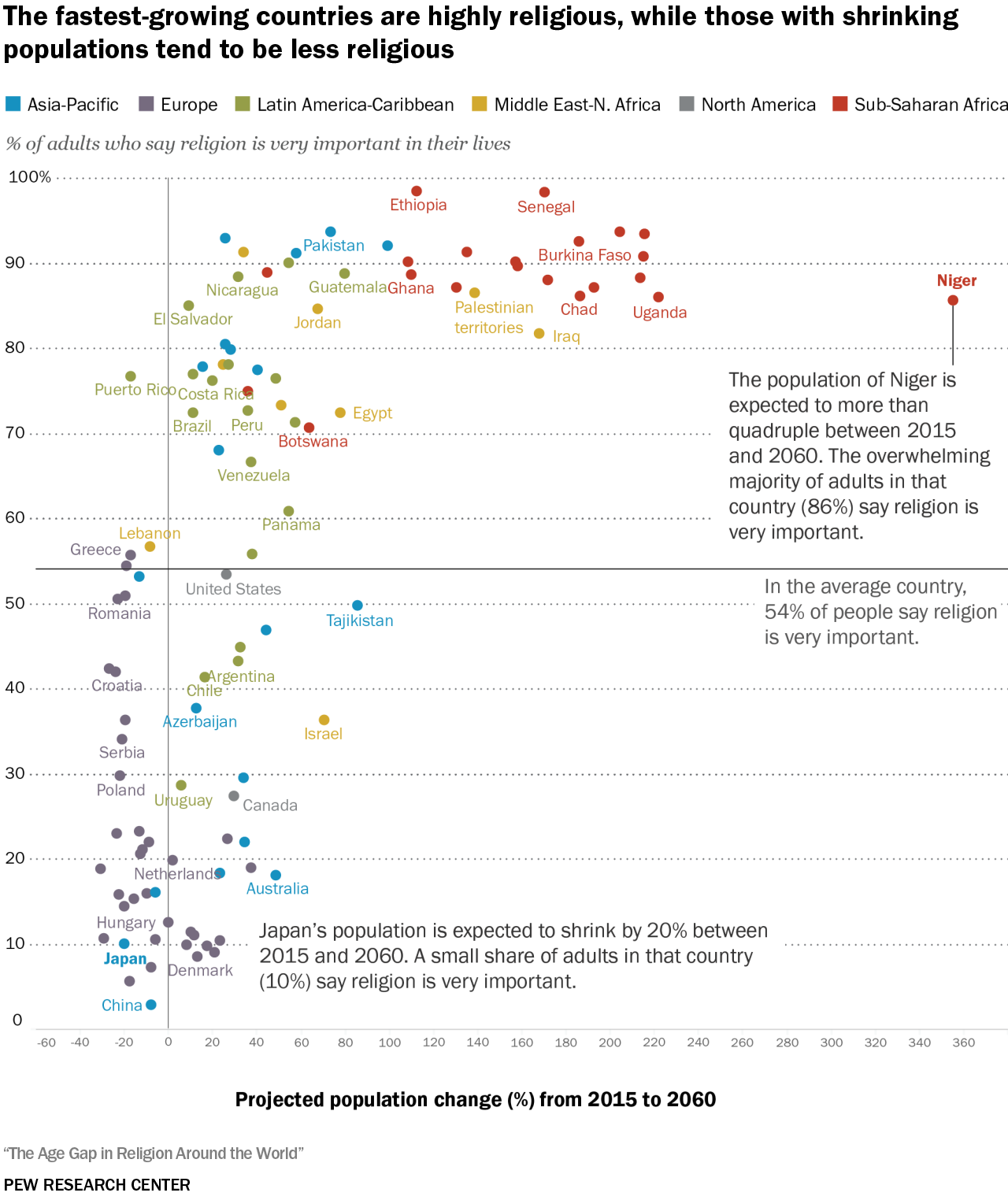

Population growth is faster in highly religious countries

At the same time, large parts of the world now have low birth rates. This includes not only Western Europe and North America, but also China, where a majority of the world’s religiously unaffiliated population lives (and where the government imposed a “one-child policy” from 1980 until 2016).

Meanwhile, some highly religious regions are experiencing rapid population growth. In Africa and the Middle East, for example, the average woman has more children than in Europe, North America or East Asia – and much larger shares of the population, both young and old, in these parts of the world say religion is very important to them.

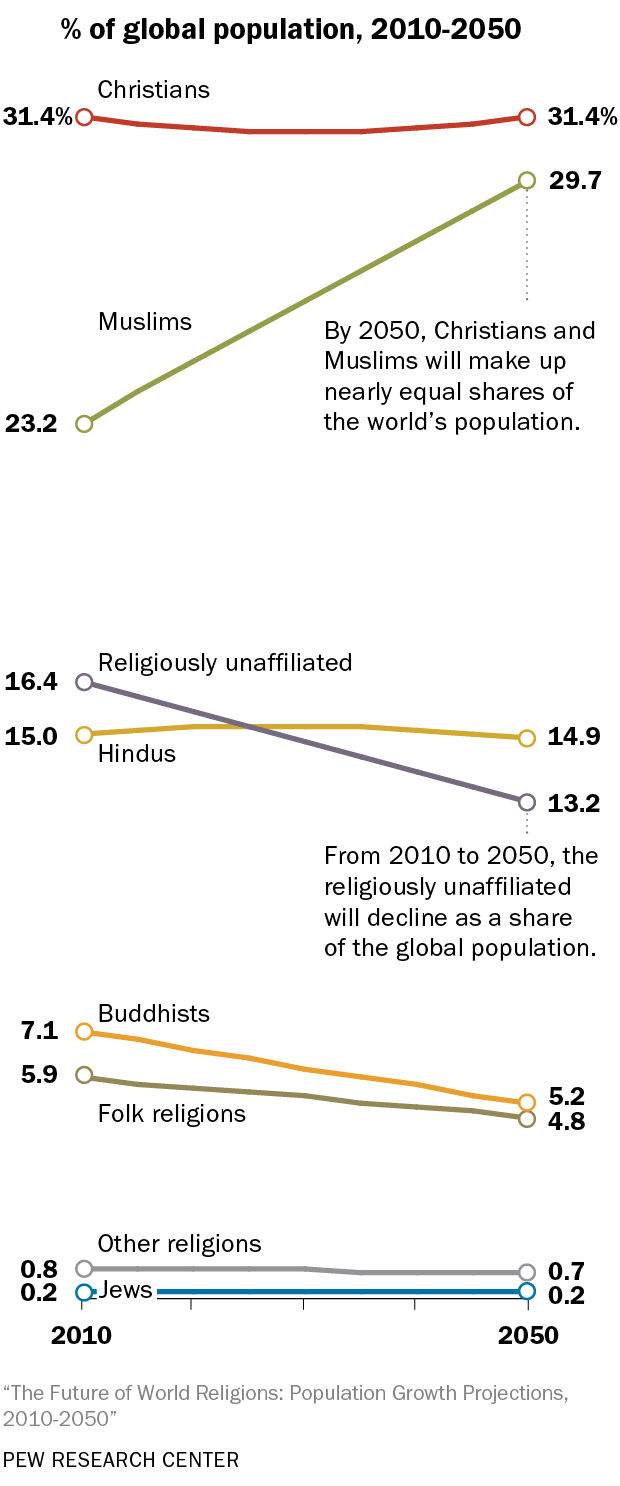

Vast majority of world’s population is projected to have a religion

Differing fertility rates and other demographic data are factored into our population growth projections for the world’s major religious groups, which forecast that the percentage of the global population that is religiously unaffiliated will shrink in the decades ahead – in contrast with the trend seen in the U.S. and Western Europe.

The projections anticipate that the vast majority of the world’s people will continue to identify with a religion, including about six-in-ten who will be either Christian (31%) or Muslim (30%) in 2050. Just 13% are projected to have no religion.

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region with the fastest population growth. Its high birth rates are a major contributor to the increasing size of the world’s Christian and Muslim populations. In coming decades, Muslims are expected to grow faster than any other major religious group, rivaling or surpassing Christians as the world’s largest religious group before the end of this century.

Meanwhile, rapid population growth in Africa – along with much slower growth or even declines in Europe and North America – will shift the geographic center of Christianity. By 2060, more than four-in-ten of the world’s Christians are projected to live in sub-Saharan Africa, while fewer than a quarter will live in Europe and North America combined, if current trends continue.

We are tracking these trends and working to produce new estimates of the religious composition of countries around the world as new data comes in, although the latest round of censuses and some key surveys have been delayed in many countries by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interactive: Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050

Is religion gaining or losing influence? Depends where you are

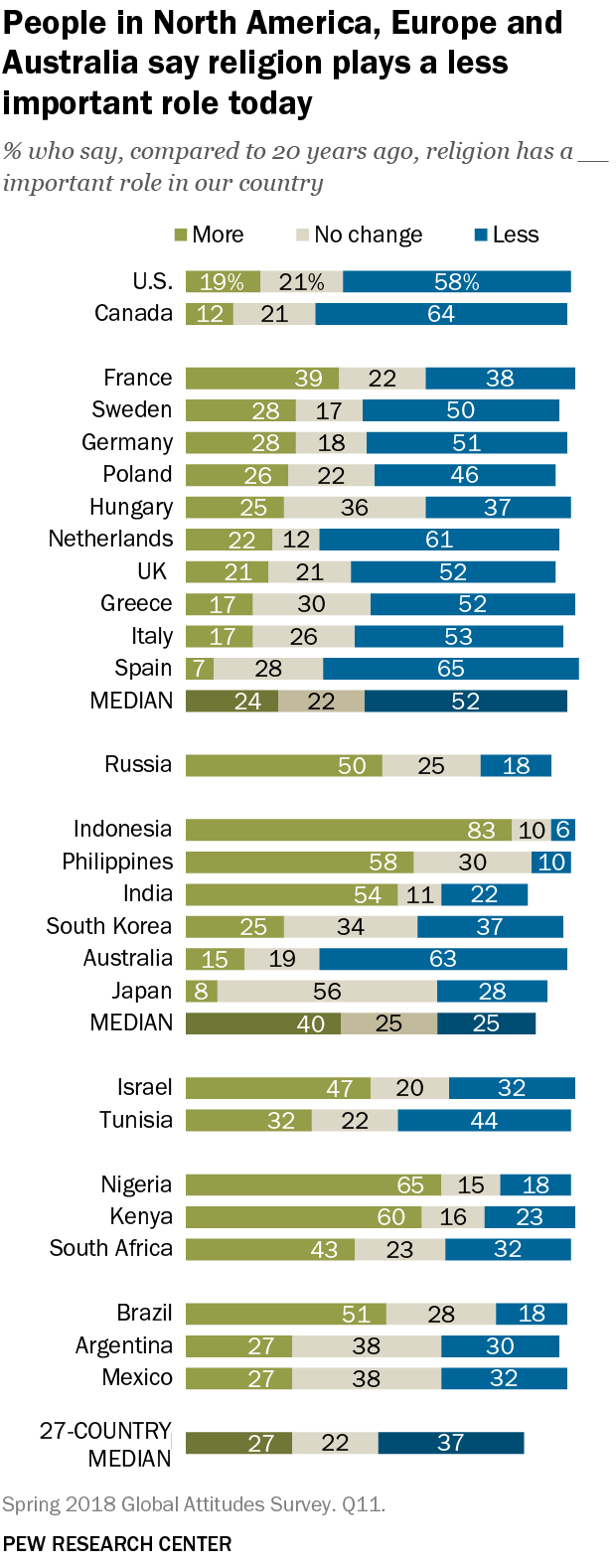

A 2018 Pew Research Center survey asked people in 27 countries whether they think religion plays a more or less important role in their nation than it did 20 years earlier. In most countries surveyed – including the U.S. – more people said the role of religion has decreased than said it had increased. But there were plenty of exceptions, including such countries as Indonesia, Kenya, Brazil and Israel, where the balance of public opinion was that religion’s role in their societies had increased in recent decades.

Religion also appears to have made a partial resurgence in the former Soviet Union, where it was long repressed under communist rule. The share of people identifying as Christians rose rapidly in several former Soviet republics after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. In Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the Russian Orthodox Church has returned to political prominence, becoming an important element of national identity for many citizens there.

China is another country where communist politics led to repression of religion and where it remains difficult to obtain reliable measures of religious activity. Pew Research Center has been tracking restrictions on religion around the world for more than a decade, and China’s government has consistently ranked among the most restrictive, alongside Egypt, Iran and other countries.

Trends in religious freedom

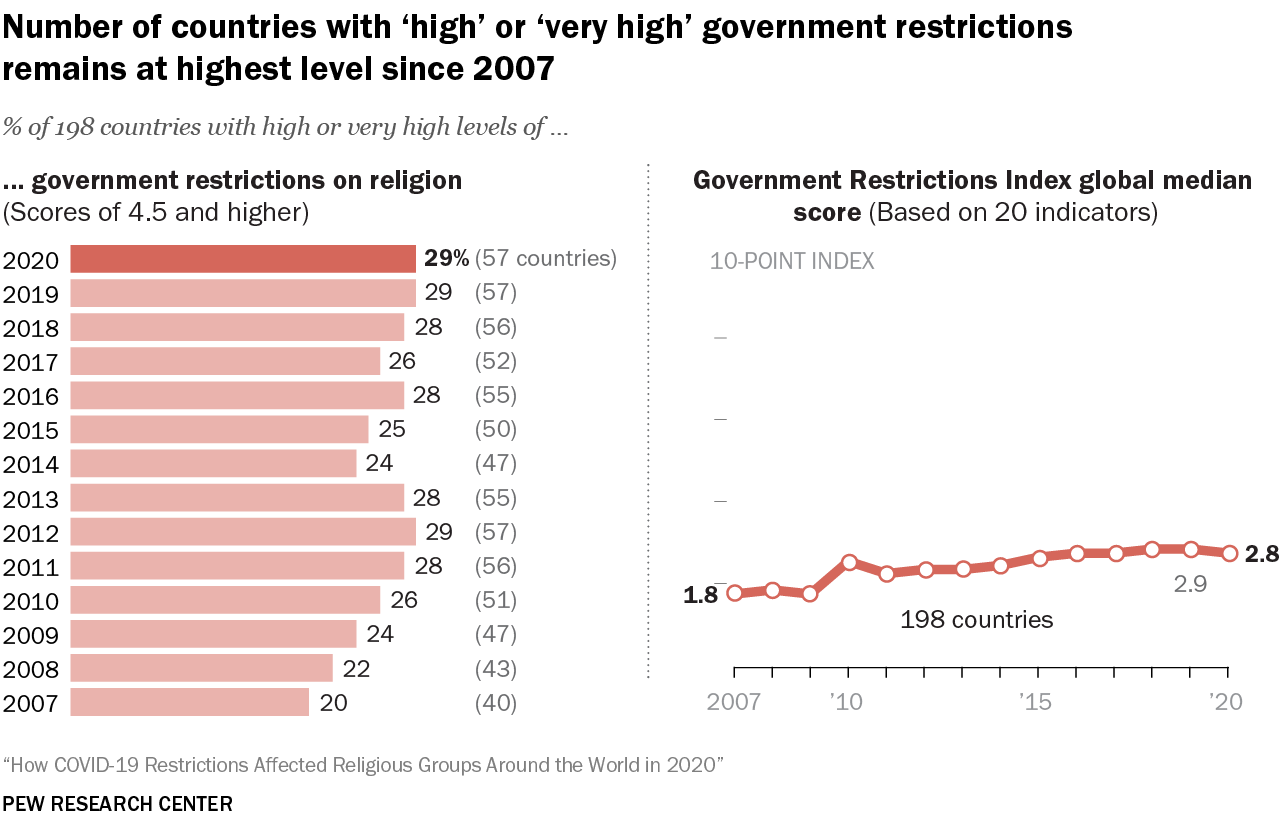

Overall, government restrictions on religion have been rising globally. As of 2020, 57 countries now have “very high” levels of government restrictions on religion, up from 40 in 2007, the baseline year of the study. These restrictions can take many forms, including efforts by governments to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversions, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to certain religious groups.

More than 80 countries have either an official state religion or a clearly favored religion. And among the 43 countries with state religions, a majority – 27 (or 63%) – are Islamic, including a broad swath of countries stretching across North Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, from Morocco to Pakistan.

For many people in these countries, religion can’t be separated from the power of the state. In a series of surveys conducted from 2008 to 2012, nearly all Muslims in Afghanistan (99%), nine-in-ten in Iraq (91%) and large majorities elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and South Asia said Shariah – Islamic law – should be the official law of the land in their country. (The survey found much lower support for religious law among Muslims in the post-Soviet republics of Central Asia and in the Balkans.)

On the other hand, Muslims around the world don’t necessarily agree on what Shariah means in practice. Some say Shariah should be open to multiple interpretations. Many favor applying it in matters of family law, such as divorces and inheritances, but not in criminal cases. And even among Muslims supporting Shariah, majorities in many countries say it should apply only to Muslims, not to people of other faiths – although some of those countries enforce laws against blasphemy and apostasy (the act of leaving one’s religion), limiting possibilities for secularization or religious change within their borders.

Religion’s role as a uniter and divider

The decline of religion in the West has caused people to ask: Is this a good thing or a bad thing for individuals and society?

There is no easy answer. Our research has found elements of religion that could be considered both positive and negative. Of course, religion brings meaning and purpose to many people’s lives – even in highly secular Western Europe, a median of 39% say that religion does this – while also providing solace in times of grief and moral guidance when making difficult decisions.

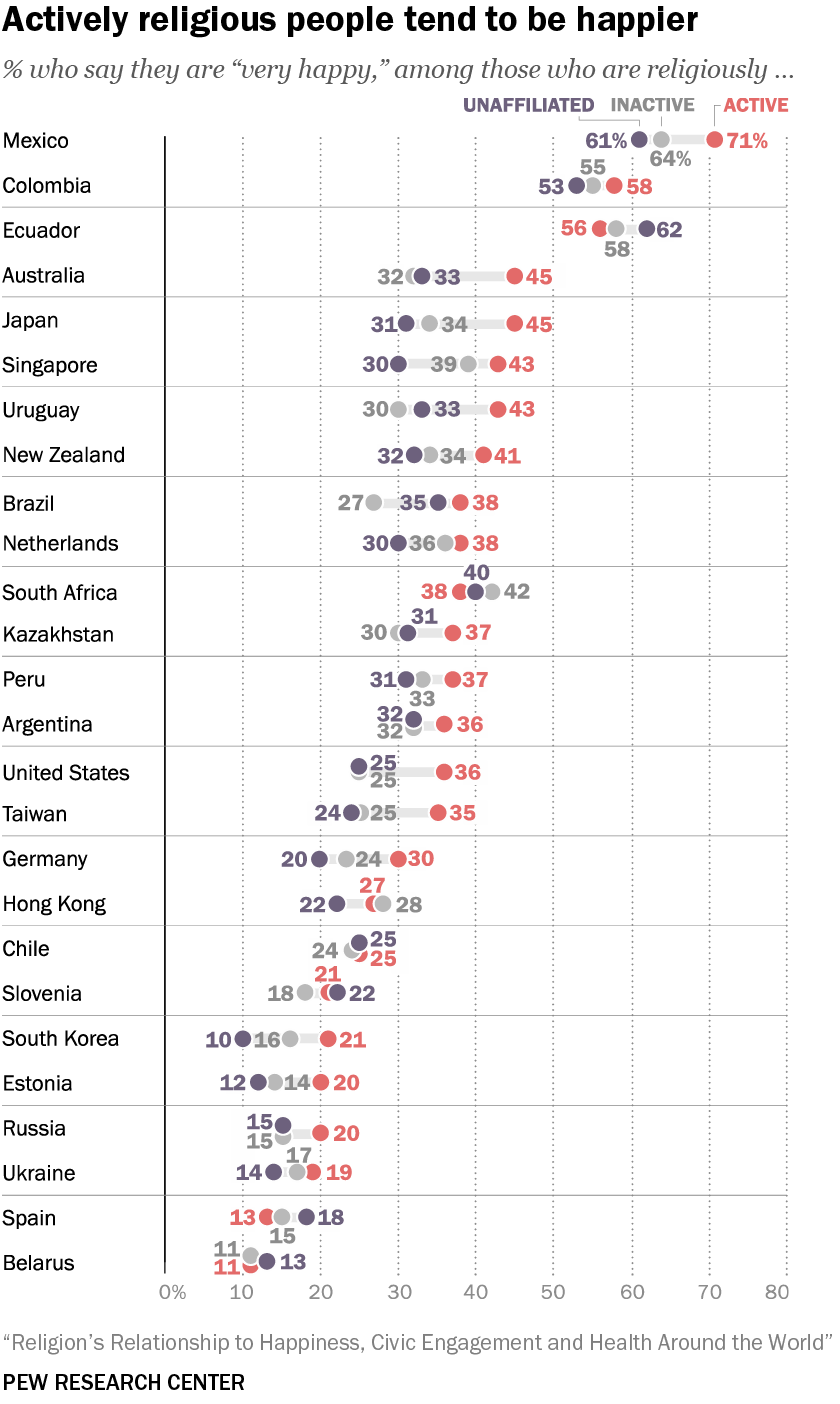

In addition, people who are active in religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged than either religiously unaffiliated adults or inactive members of religious groups, according to a 2019 Center analysis of survey data from the United States and more than two dozen other countries.

This sense of community may be what many people imagine when they think of organized religion: About half of Americans (52%) say religion mostly brings people together, while just one-in-five say it mostly pushes people apart. And people around the world, in many different religious groups, generally express pride in being a member of their group.

But there is also evidence of the divisive power of religion, and not just in U.S. politics. In India – the world’s largest democracy, which the United Nations projects will surpass China as the world’s most populous country in 2023 – people of all major faiths see religious tolerance as a core national value, according to a survey we conducted of nearly 30,000 Indians in 2019-2020. But most Indians also say it is important to stop interreligious marriages, and many say they would not accept a person of another faith as a neighbor, making religion a key dividing line between groups in Indian society, the survey found.

In Israel, there are deep divisions not only between Jews and Palestinians, but also within the Jewish majority. Israeli Jews disagree sharply about the role of religion in national life. In our 2014-2015 survey of Israel, 93% of secular Jews in Israel said they would be uncomfortable with the prospect of their child marrying a Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) Jew, while 95% of the ultra-Orthodox said the same about their child marrying a secular Jew.

Western Europe also provides a striking example of the connection between religious identity and social divides: Christians as a whole in the region tend to express higher levels of nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-religious minority sentiment than their religiously unaffiliated neighbors. This is not to say that most Christians in Europe oppose immigration or want to keep Muslims and Jews out of their neighborhoods. But Christian identity, on its own, is associated with higher levels of nationalism and negative views of religious minorities and immigrants, as we found in a 2017 survey across 15 countries in Western Europe.

Does economic prosperity bring secularization?

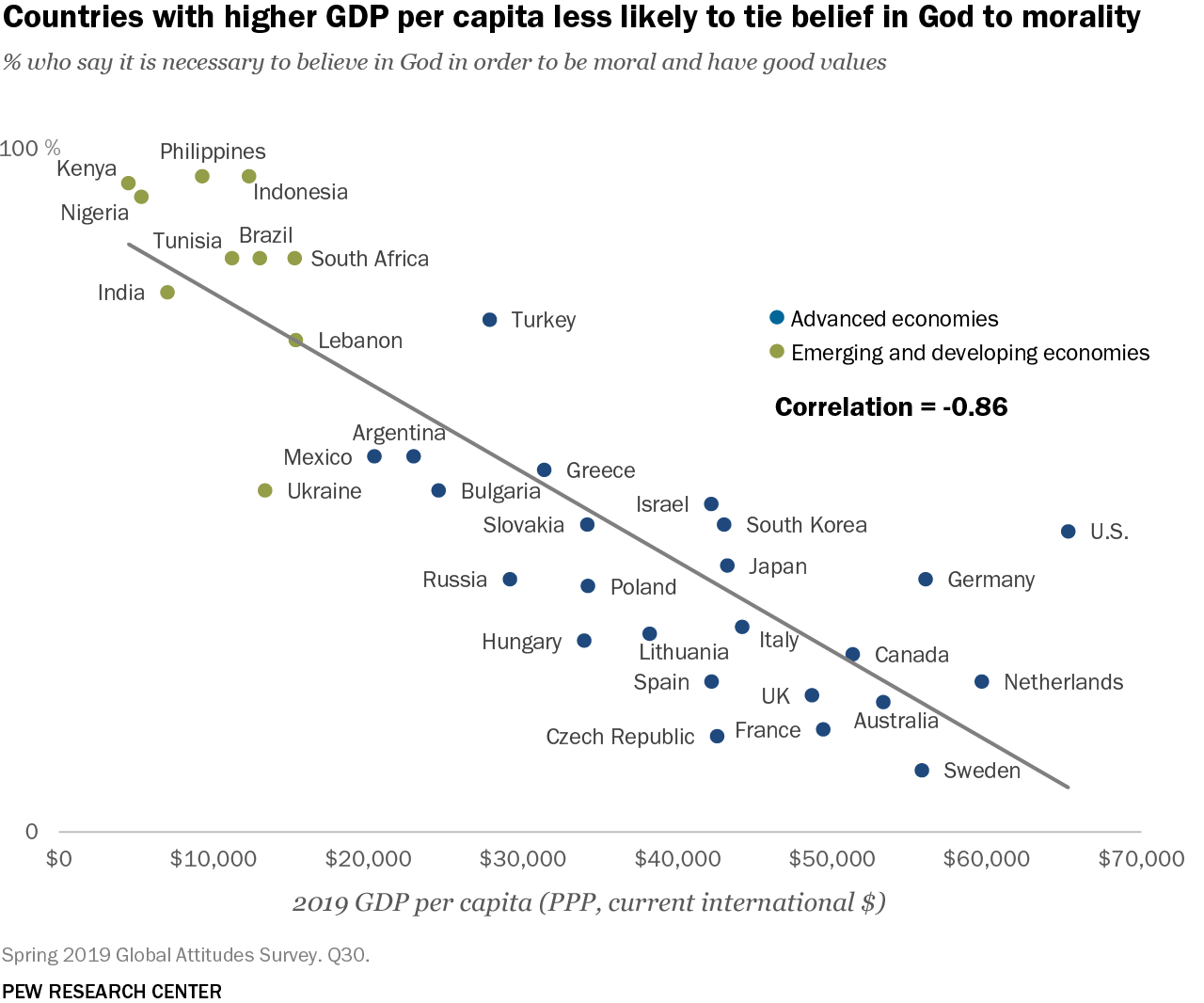

Around the world, there is a clear correlation between higher economic advancement and lower religious commitment – using several different measures of both concepts. For instance, in countries with higher gross domestic products per capita (a rough measure of economic prosperity), people tend to be less likely to pray, or to say that a person must believe in God to be moral and have good values.

This raises the question: Is the whole world headed in the same direction? If humanity continues to advance scientifically, technologically and economically, is it only a matter of time before religion fades away? Karl Marx famously thought so, and some theorists still do. But Pew Research Center’s global surveys and demographic studies have revealed a more complicated picture.

On the one hand, as previously noted, the fastest-growing countries tend to be highly religious, while those with shrinking populations tend to be less religious. This suggests that, at least for a time, the share of the world’s population that is religious may rise, not fall.

On the other hand, in many countries around the world, younger people are less religious than older people. (Of more than 100 countries surveyed, there are 46 in which people ages 18 to 39 consider religion less important than those 40 and older. In 58 countries, there is no statistically significant difference between age groups. There are just two countries – Georgia and Ghana – where younger people consider religion more important than older people do.) Of course, this could be because human beings tend to become more religious as they age. But it’s also exactly the pattern one would expect to see if many countries are gradually becoming more secular, generation by generation.

Religion’s intersections with gender and education

Our studies also find that, on average, women are notably more religious than men in the United States and many other countries, particularly in places with Christian majorities. But it’s far from a universal pattern. Men display higher levels of religious commitment than women in some countries and religious groups, and in other contexts, there are few, if any, gender differences.

The relationship between education and religion is also more complex than it might seem on the surface. In the United States, people with college and post-graduate degrees tend to be less religious than those with only a high school education. But highly educated Christians are just as religious, on average, as less educated Christians, and they are more likely to say they are weekly churchgoers.

Globally, our studies show that some world religions lag considerably behind others in terms of average education levels, as well as that Muslim and Hindu women tend to have fewer years of schooling than men in those same religious groups. But there are strong signs of progress across the board: All major faiths have made gains in average years of schooling, and the gender gaps have started to narrow.

More global studies are in the works. After completing a massive survey on religion across India – including relations among Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs and Christians in that country – the Global Religious Futures project is turning toward Southeast Asia and East Asia. In the past, some countries in those regions have ranked low on measures of religion that originally were developed for Western countries and Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Islam and Christianity). But new measures, designed specifically for East Asian populations, will seek to dig deeper into the role of religion in daily life in the region.