Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

Ancestor veneration is important across East Asia and Vietnam. It takes many different forms and is tied to the traditional belief that ancestors’ spirits remain in one’s family and can intervene in human affairs.

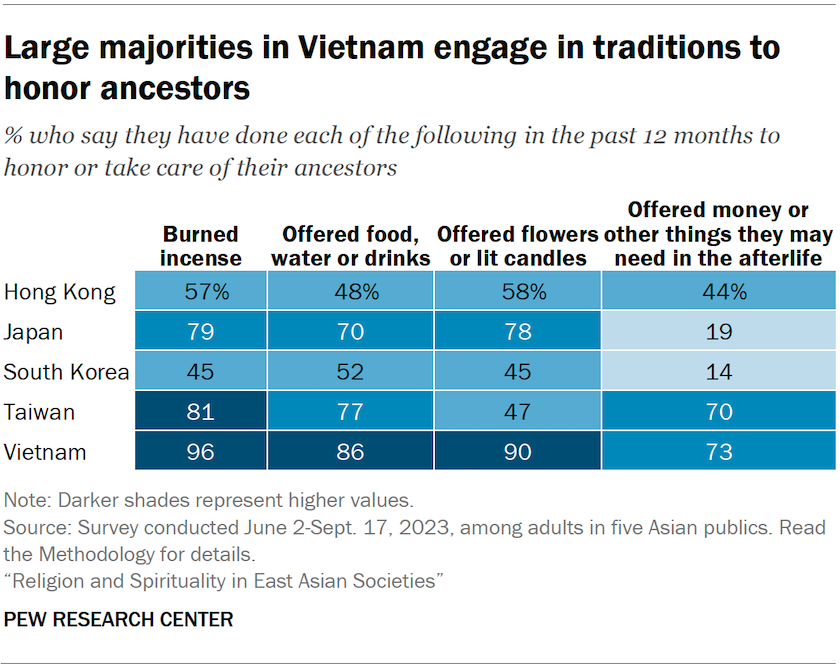

Traditional ancestor veneration practices involve gravesite maintenance (or “tomb sweeping”); burning incense to honor ancestors; leaving offerings of food or drink at gravesites or ancestral altars, particularly during certain holidays; and making offerings of spirit money or other goods believed to be necessary to ensure the comfort and happiness of ancestors in the afterlife.

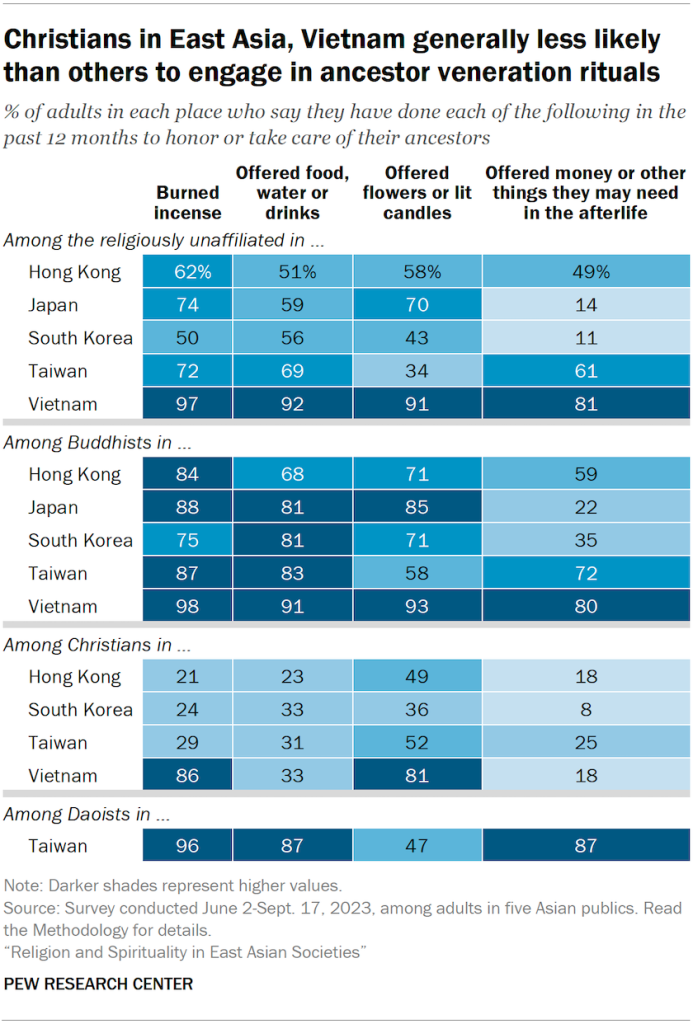

Across the region, 50% of religiously unaffiliated adults or more, as well as the vast majority of Buddhists, say they have burned incense for their ancestors in the past 12 months. In most of the five societies surveyed, a majority of Buddhists and unaffiliated people also say they have offered food, water or drinks to their ancestors in the past year.

Far fewer Christians engage in these types of activities, except in Vietnam. There, 86% of Christians say they have burned incense and 81% say they have offered flowers or lit candles in honor of ancestors in the past year. (According to historians, Vietnamese Christians were persecuted in the 19th century in part because Christianity was viewed as opposing the ancestor rites that were a cornerstone of Vietnamese society. Today, some Catholic authorities in Vietnam prefer to describe ancestor-focused traditions as veneration, rather than worship.)

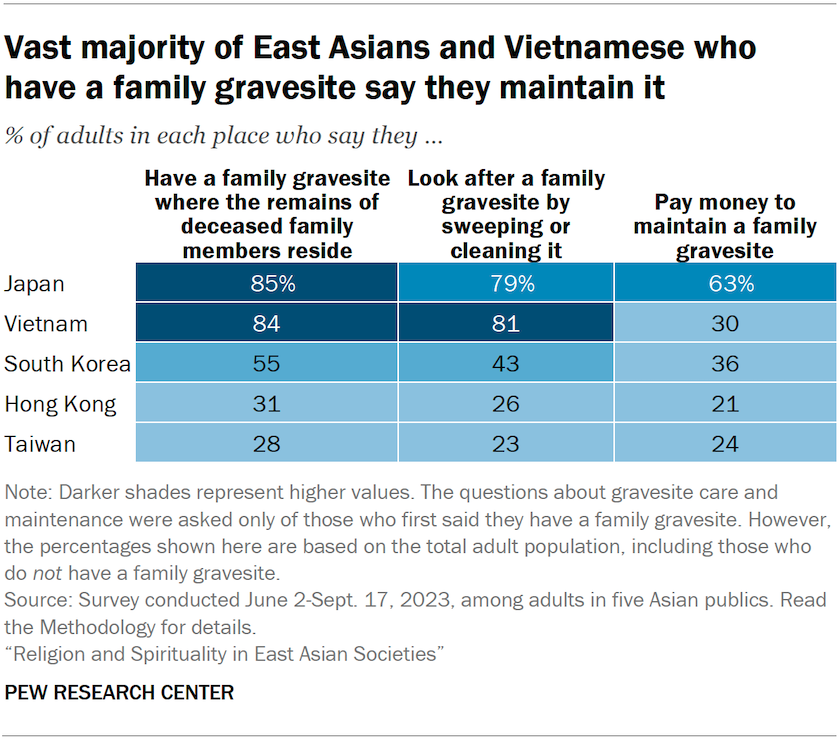

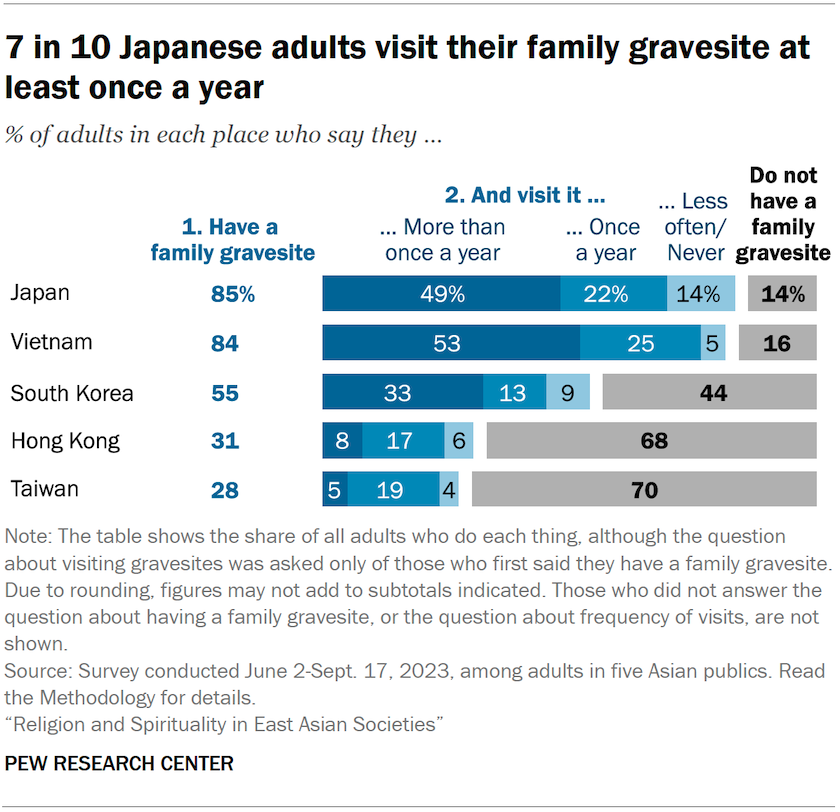

In this survey, most respondents in Japan and Vietnam say they have a family gravesite, and majorities in both countries also say they look after the gravesite by cleaning it. Smaller shares in South Korea, Hong Kong and Taiwan have a family gravesite. But among people who do have a family gravesite, overwhelming majorities across the region say they visit it at least once a year.

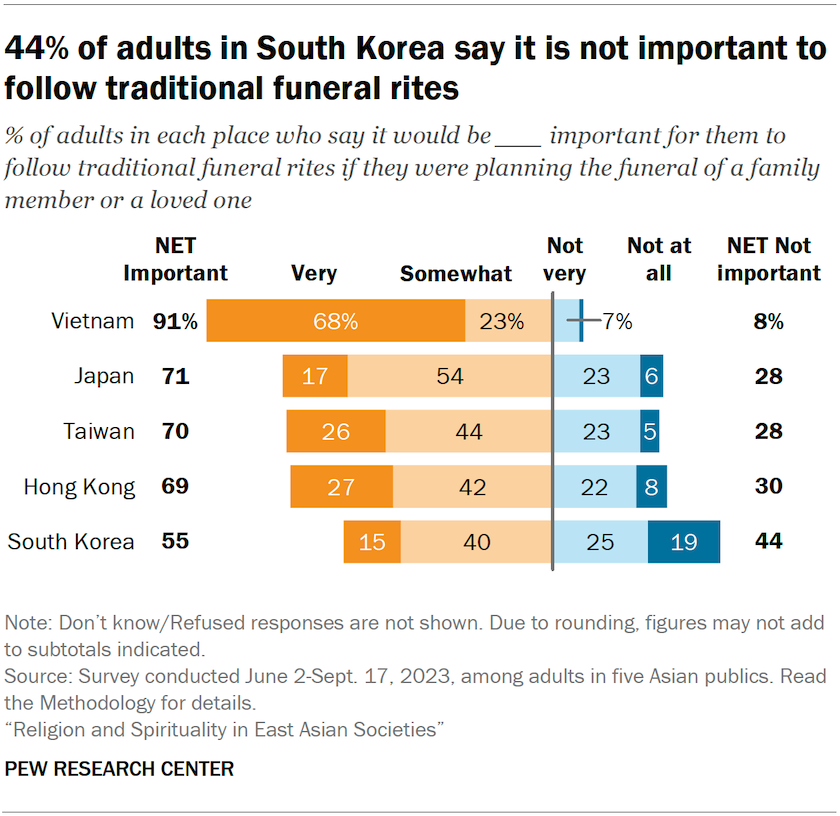

Throughout the region, people say it is important to follow traditional practices when planning a loved one’s funeral. For example, about seven-in-ten adults in both Japan and Taiwan say that following traditional funeral rites is important.

The survey also asked about:

Ancestor veneration rituals

In each of the five places surveyed, large shares of the population say they have done the following in the past 12 months to honor or take care of their ancestors:

- Burned incense

- Offered food, water or drinks

- Offered flowers or lit candles

In East Asia and Vietnam, these activities often occur at gravesites or home altars, though the survey did not specify any location. (More about the prevalence of home altars can be found in Chapter 4.)

Ancestor veneration rituals are particularly common in Vietnam, where 96% of adults say they have burned incense in the past 12 months and 90% report that they have offered flowers or lit candles to honor their ancestors. In Taiwan and Japan, roughly eight-in-ten people surveyed have burned incense to honor ancestors in the past year.

Among the practices we asked about, the least common is offering ancestors “money or other things” that they may need in the afterlife. Still, majorities in Vietnam and Taiwan say they have made such offerings in the past 12 months.

Generally, Buddhists are more likely than people with no religion to honor ancestors in these ways, and people with no religious affiliation are more likely than Christians to do so. But in Vietnam, a solid majority of Christians have burned incense (86%) and offered flowers or lit candles (81%) for ancestors in the past year.

Respondents ages 60 and older are somewhat more likely than younger adults to say they have burned incense and offered flowers or lit candles to honor ancestors in the past 12 months. And men are more likely than women to say they have burned incense for ancestors in the past year.

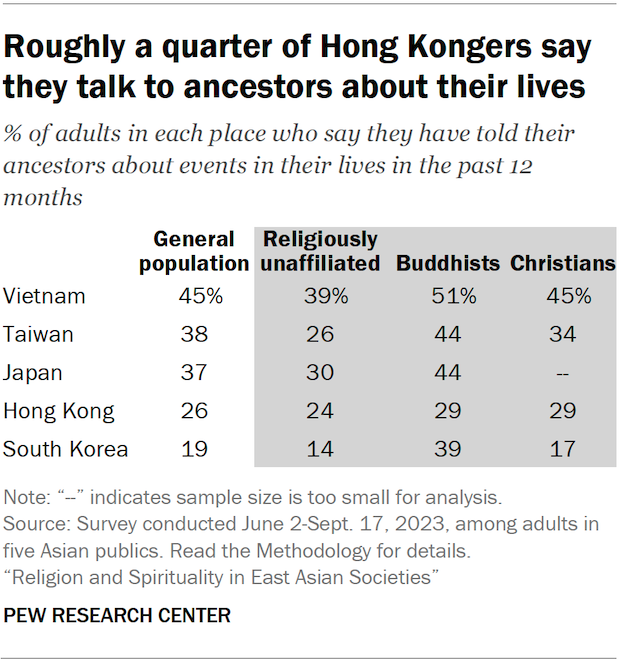

Communicating with ancestors

Fewer than half of respondents throughout the region say they have told ancestors about events in their lives during the past 12 months. This practice is most common in Vietnam (45%), Taiwan (38%) and Japan (37%).

Buddhists are generally more likely than Christians and the religiously unaffiliated to say they have spoken to their ancestors about what is happening in their lives.

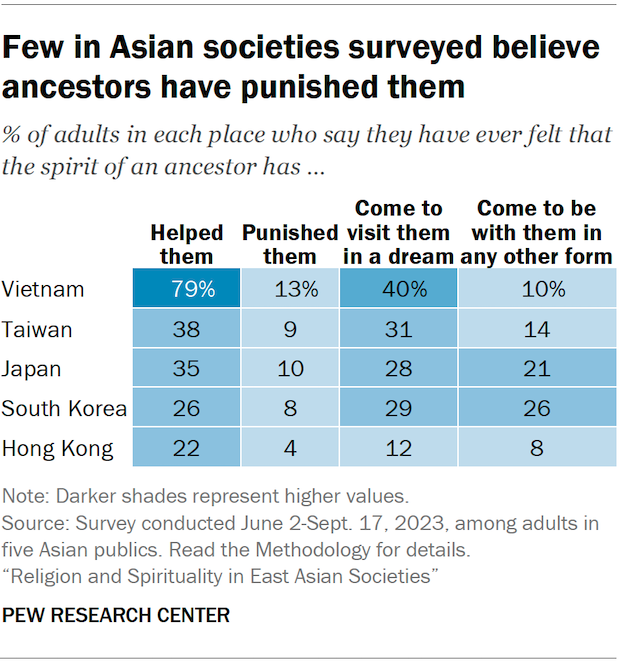

We also asked respondents whether they have ever felt the spirit of an ancestor interact with them in certain ways, such as by helping them, punishing them, coming to visit them in a dream, or coming to be with them in any other form.

In most places surveyed, fewer than half of respondents say they have had these experiences. Feeling that an ancestor has punished them is particularly rare.

But Vietnam stands out on one measure: Nearly eight-in-ten Vietnamese adults say the spirit of an ancestor has ever helped them.

Buddhists across the region are more likely than the religiously unaffiliated and Christians to say they have felt spirits either help or punish them. For example, South Korean Buddhists (53%) are more than twice as likely as the religiously unaffiliated (22%) or Christians (20%) to say they have felt the spirit of an ancestor help them.

Also, women are more likely than men to say ancestors have visited them in a dream. And adults ages 60 and older are more likely than younger adults to report this experience.

Family gravesites

Family gravesites, which can include places where cremated ashes are interred, are extremely common in some, but not all, of the five societies surveyed.

In Japan and Vietnam, more than eight-in-ten adults say they have a gravesite where the ashes or remains of deceased family members reside. In South Korea, just over half say this, while in Hong Kong and Taiwan, about one-in-three adults have family gravesites.

Among survey respondents who report having a family gravesite, the vast majority say they (or others in their household) look after it by sweeping or cleaning it. For example, 28% of adults in Taiwan say they have a family gravesite, and most of these respondents (23% of all Taiwanese surveyed) say that someone in their household sweeps or cleans it.

Across the region, people are less likely to say they pay money to maintain family gravesites, though in Japan a majority of adults say they (or others in their household) pay for this upkeep.

Most East Asians and Vietnamese who have a family gravesite say they visit it at least once a year. For example, in Taiwan, 28% of adults say they have a family gravesite, and 24% of all adults (or 86% of those who have a family gravesite) say they visit it once a year or more.

In Vietnam and Japan, where family gravesites are much more common, seven-in-ten adults or more say they visit theirs at least once a year. And in both places, roughly one-in-ten adults say they visit their family gravesite at least monthly (12% and 8%, respectively).

How important are traditional funerals?

Although funeral rites vary across the region, most respondents in all five places surveyed say it would be at least somewhat important to follow tradition if they were planning a funeral for a family member or loved one.

In Vietnam, about nine-in-ten adults say this, including 68% who say it would be very important to follow traditional funeral rites and rituals. Previous research has shown that planning a parent’s funeral is among life’s greatest responsibilities in Vietnam. These funeral proceedings can last for quite some time, and they often are a joint effort with many members of the family and community.

Generally across the region, Buddhists are more likely than Christians or adults without a religious affiliation to say it would be important to follow traditional rituals at a loved one’s funeral. But even among Christians and the religiously unaffiliated, about half or more say it would be at least somewhat important to do this. For example, in South Korea, 71% of Buddhists, 49% of Christians and 54% of the religiously unaffiliated say this.

(For more on Buddhists’ views about the importance of Buddhist funerals to Buddhist identity, read Chapter 2.)

In several places across the region, women are more likely than men to say that traditional funeral rituals would be important. In South Korea and Taiwan, however, men and women are about equally likely to prioritize traditional rites.

Cremation and burial

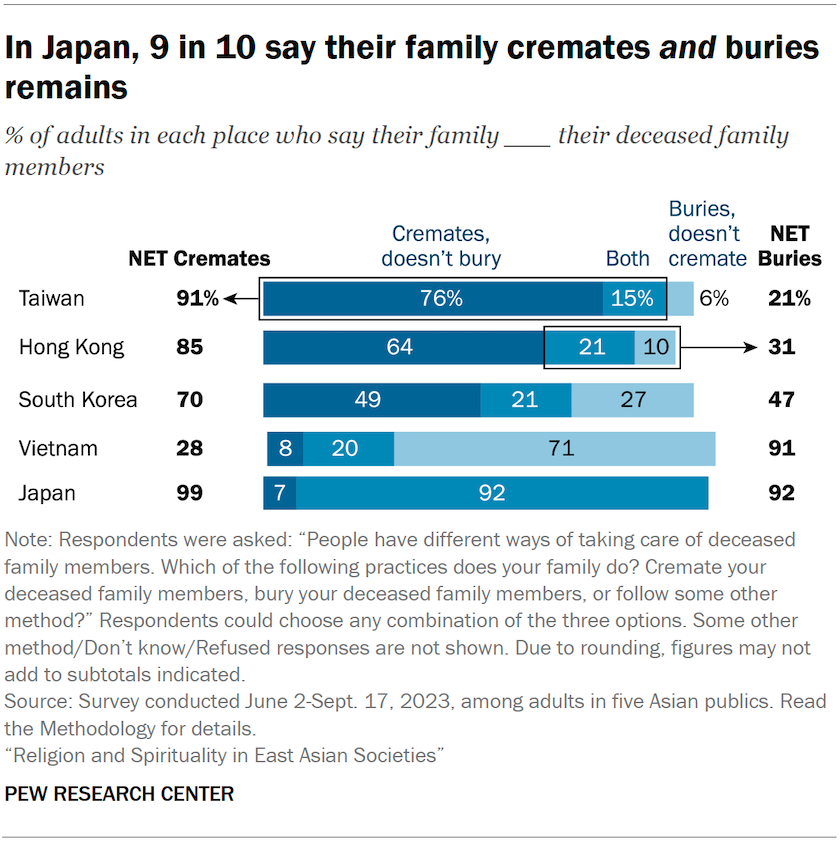

In this region, the question of how to handle the remains of the dead is widely debated for many reasons, including concerns about land scarcity and groundwater pollution, as well as evolving funeral customs.

Survey respondents were asked how their family takes care of the remains of deceased family members. The options we gave were cremation, burial or “follow some other method.” People could select more than one option.

Large majorities in four of the surveyed places say they cremate deceased family members. Vietnam is the only place in the region where burial is more common than cremation (91% vs. 28%).

No more than 6% in any place say their family follows some other method.

In Japan, 92% of adults say their family both cremates and buries deceased family members. Far fewer adults in other places report choosing both cremation and burial for dead relatives.

Outside Japan, majorities say their family either cremates or buries dead relatives. In South Korea, 49% of respondents say their family cremates without burying, while 27% say their family buries without cremating.

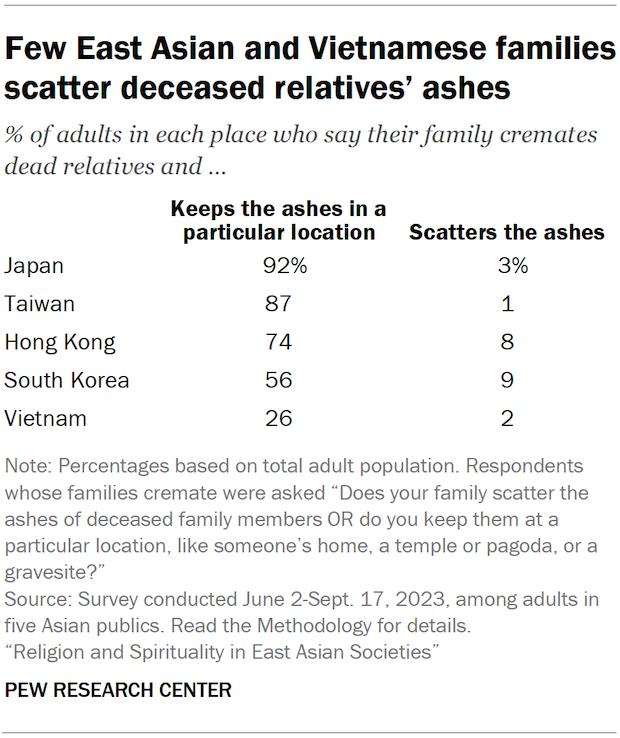

Survey respondents who reported that their family cremates deceased relatives were then asked whether they scatter the ashes or keep them in “a particular location, like someone’s home, a temple or pagoda, or a gravesite.”

Keeping ashes in a particular location is the most common approach. Large majorities in Japan (92%), Taiwan (87%) and Hong Kong (74%) say they do this.

Belief in rebirth and nirvana

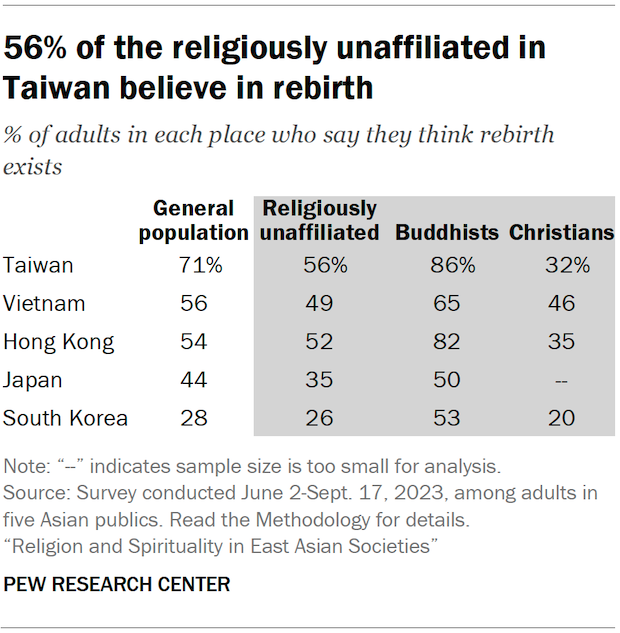

The belief that humans are reborn in an ongoing cycle of suffering known as samsara is a core teaching in Buddhism, and at least half of Buddhists in all five locations surveyed say they think rebirth exists.

Religiously unaffiliated adults are less likely than Buddhists to say they believe in rebirth. Still, significant shares of the religiously unaffiliated in Taiwan (56%), Hong Kong (52%) and Vietnam (49%) say they believe in rebirth.

In Taiwan, roughly eight-in-ten Daoists (also spelled Taoists) and followers of local or Indigenous religions also say they believe in rebirth.

Across the region, women are more likely than men to say they believe in rebirth. In Japan, for example, 51% of women believe in rebirth, compared with 37% of men. Adults younger than 60 are also more likely than the region’s older adults to say rebirth exists.

(Reincarnation is a related concept in Hinduism. Our 2019-2020 survey of religion in India found that 40% of Hindus in India believe in reincarnation.)

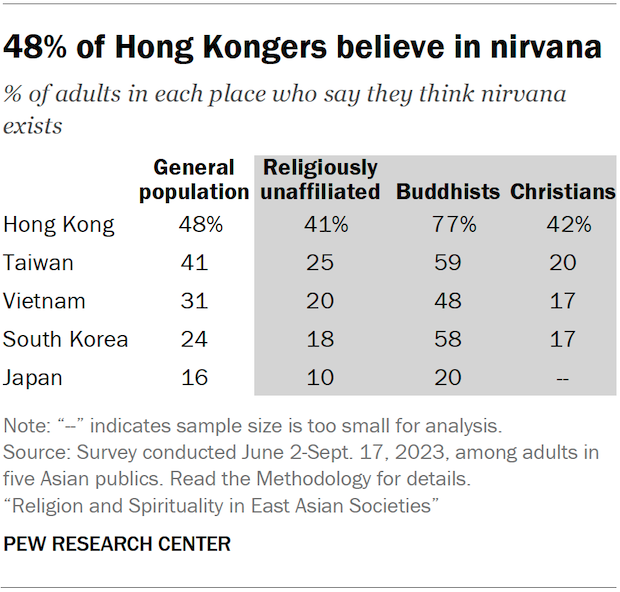

Respondents also were asked whether they believe in nirvana – a term used in Buddhist teachings to refer to the state of liberation from the cycle of rebirth. Buddhists in Hong Kong (77%), Taiwan (59%) and South Korea (58%) are the only religious groups with a majority that believes in nirvana.

Across the places surveyed, the religiously unaffiliated and Christians are much less likely than Buddhists to believe in nirvana. For example, 48% of Vietnamese Buddhists say they believe in nirvana, compared with 20% of religiously unaffiliated Vietnamese adults and 17% of Vietnamese Christians.

(In every place but Hong Kong, sizable shares chose not to answer this question. This ranged from 16% in South Korea to 30% in Taiwan.)

Belief in heaven and hell

Many world religions have concepts that can be understood as “heaven” and “hell,” even though religions may define or describe these places differently. For example, while Christianity describes heaven and hell as final destinations for souls of the dead, Buddhism teaches that heaven and hell are among the many temporary locations that a soul can be reborn into before escaping the cycle of rebirth.

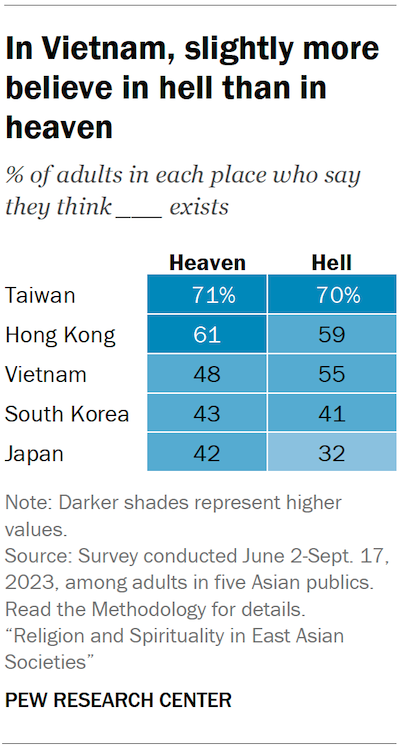

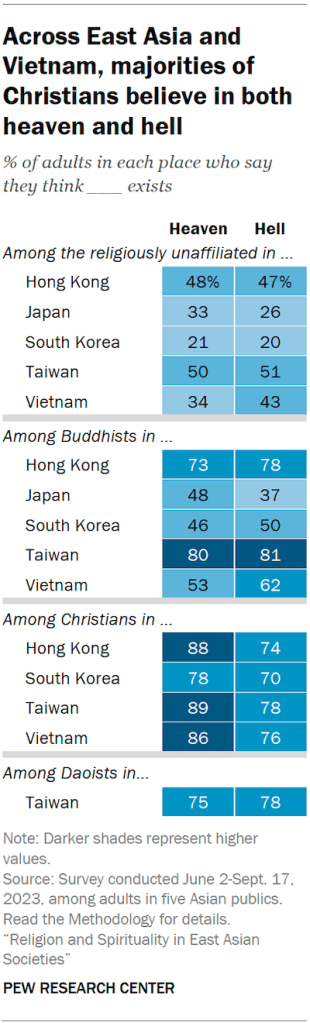

In Hong Kong and Taiwan, clear majorities say they believe in both heaven and hell. In Vietnam, the public is more evenly divided, with 48% expressing belief in heaven and 55% in hell. Meanwhile, in Japan and South Korea, roughly four-in-ten adults believe in heaven, and somewhat fewer Japanese (32%) believe in hell.

Christians in the region typically are the most likely to say that both heaven and hell exist, though more Christians express belief in heaven than in hell.

Buddhists across the region are more likely than people who have no religion to believe in each concept. For instance, in Vietnam, the vast majority of Christians (86%) believe in heaven, compared with roughly half of Buddhists (53%) and a third of the unaffiliated (34%).

Our survey also finds that, in general:

- Adults under 60 are morelikely than older adults to say they believe in hell. In Hong Kong, for instance, 63% of adults who are younger than 60 believe in hell, compared with 49% of older adults.

- Women are more likely than men to say that both heaven and hell exist.

- Christians who say they pray at least once a day are more likely than other Christians to say they believe in both heaven and hell.