Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

Some standard ways of measuring religious beliefs, such as asking about belief in god, are grounded in monotheistic religions – particularly Judaism, Christianity and Islam – that hold there is only one God.

Such metrics may miss key elements of religious and spiritual life in East Asia and Vietnam. So while we did ask about belief in god on this survey, over the past seven years we have consulted with experts from the region to develop measurement tools that capture a much wider range of religious and spiritual beliefs.

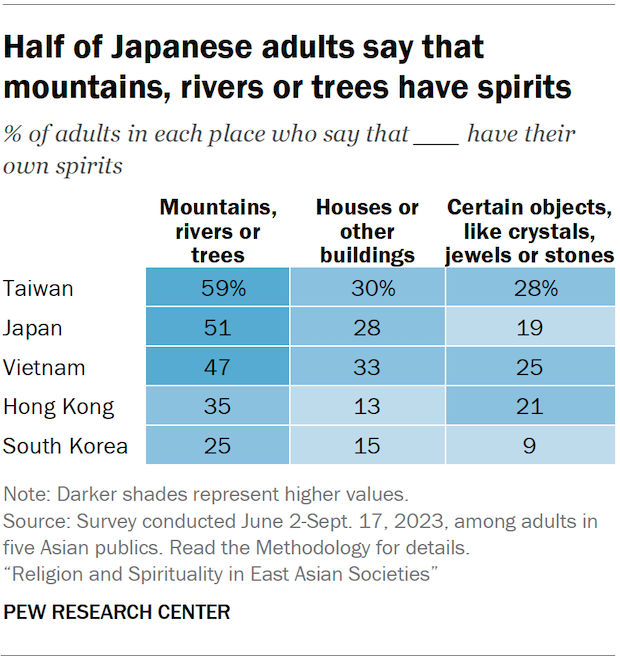

For instance, in Japan’s traditional Shinto belief system, kami are spirits or deities that inhabit the land and imbue forces of nature like the wind. To measure the prevalence of similar beliefs across the region, we devised separate questions asking whether spirits exist in the natural landscape (mountains, rivers or trees); the human-built landscape (houses or other buildings); and physical objects (crystals, jewels or stones).

We find that across the region, the belief that spirits inhabit mountains, rivers or trees is particularly widespread. Half of adults surveyed in Japan express this belief, as do 47% in Vietnam and 59% in Taiwan.

(For more information on the veneration of kami in Japan, refer to Chapter 4.)

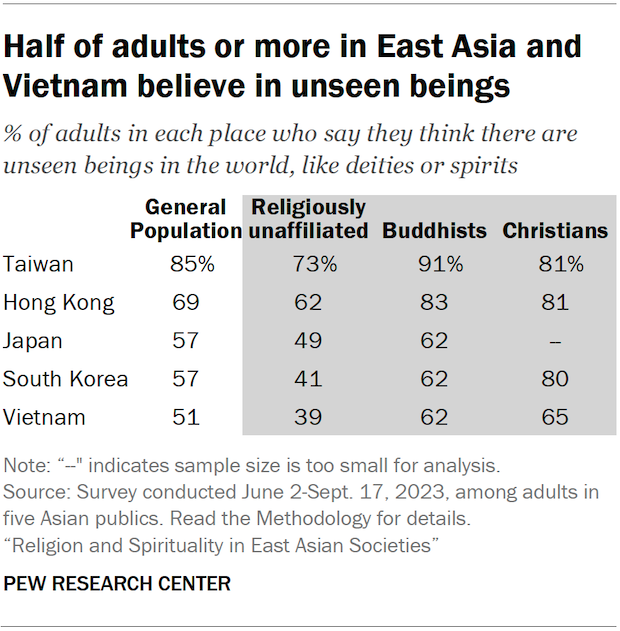

More broadly, most people in all the region’s major religious groups – Buddhists, Christians and Daoists (also spelled Taoists) – believe in the existence of unseen beings, like deities or spirits. But some religiously unaffiliated people also hold this belief: Across the region, the share of unaffiliated adults who say they believe in unseen beings ranges from 39% to 73%.

Overall, respondents in East Asia and Vietnam are more likely to say they believe in unseen beings, like deities or spirits, than to say they believe in god. Only in Taiwan does a clear majority of the public express belief in god.

Taiwanese adults also stand out as the most likely to hold several of the other beliefs measured in this survey, including belief in angels or helpful deities, fate, karma and miracles.

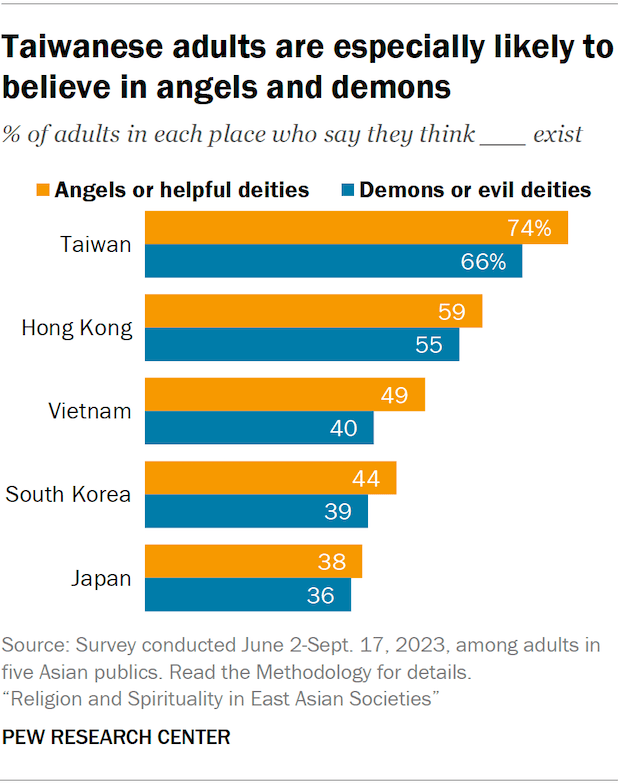

On balance, slightly larger shares tend to believe in angels or helpful deities than in demons or evil deities.

Women across the region are generally more believing than men. This aligns with a common gender divide in religiosity seen in many societies around the world.

(For information on beliefs about the afterlife – including rebirth, heaven, hell and more – go to Chapter 5.)

Belief in unseen beings

In all the places we surveyed, at least half of respondents say they believe in “unseen beings in the world, like deities or spirits.” This belief is most common in Taiwan, where 85% say they think unseen beings exist.

Buddhists and Christians are more likely than religiously unaffiliated people to say they believe in unseen beings. In South Korea, for example, 80% of Christians and 62% of Buddhists say they believe in such beings, compared with 41% of the unaffiliated.

Still, in each of the places we surveyed, roughly four-in-ten unaffiliated adults or more say they believe in unseen beings. This includes solid majorities of the unaffiliated in Taiwan (73%) and Hong Kong (62%).

Belief in unseen beings is also very common among other religious groups in Taiwan. For example, 97% of Taiwanese who identify with local or Indigenous religions say they believe in unseen beings, as do 89% of Daoists.

Respondents who have completed higher levels of education are more likely than those with less education to believe in unseen beings, like deities or spirits. For example, almost eight-in-ten college-educated residents in Hong Kong believe in unseen beings, compared with 64% of those with less education.

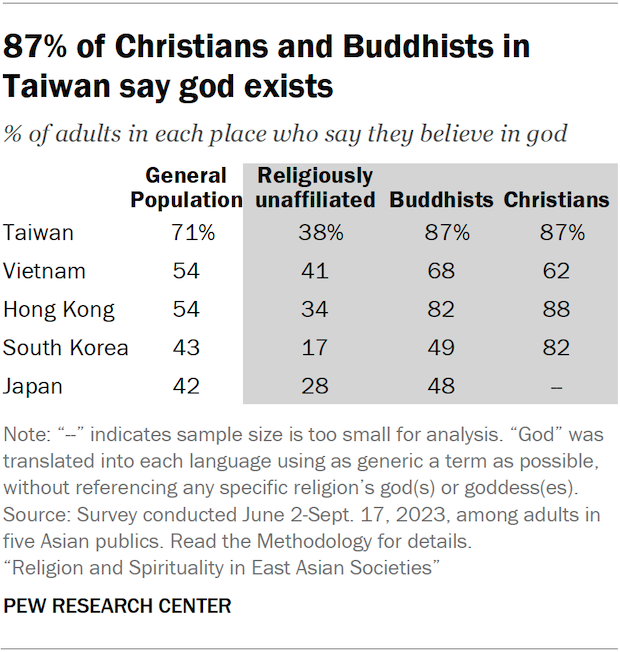

Belief in god

Views of whether god exists vary somewhat throughout East Asia and Vietnam. About seven-in-ten Taiwanese adults say they believe in god, while less than half of adults in South Korea (43%) and Japan (42%) say the same.

(The survey did not define “god,” and translators were instructed to choose as generic a term as possible, avoiding terms that refer to a specific religion’s god(s) or goddess(es). We did this so we could ask the same question of respondents in different religious groups without necessarily implying a monotheistic god.)

Majorities of Christians throughout the region say they believe in god. Among Christians, belief in god is lowest in Vietnam (62%).

And among Buddhists, belief in god is widespread in Taiwan (87%), Hong Kong (82%) and, to a lesser extent, Vietnam (68%). Even though belief in god is not considered an essential aspect of Buddhism, there is no significant difference between the rates at which Buddhists and Christians in these three places express belief in god.

Substantial minorities of religiously unaffiliated adults surveyed also say they believe in god. For example, 38% of Taiwanese respondents who identify with no religion say they believe in god.

In general, younger adults (ages 18 to 34) are somewhat less likely than older adults (35 and older) across the region to believe in god. But the opposite is true in Vietnam, where younger adults are slightly more likely than older adults to express belief in god (58% vs. 52%).

Belief in god compared with belief in unseen beings

People throughout the region typically are more likely to say they believe in unseen beings, like deities or spirits, than in god.

This trend is largely driven by religiously unaffiliated people. In four of the five places we surveyed, the difference is at least 20 percentage points, with the widest gap in Taiwan: 73% of religiously unaffiliated Taiwanese adults say unseen beings exist, but only 38% believe in god.

Among Christians, these differences are generally much smaller and not statistically significant. In Hong Kong, though, the pattern is reversed: Slightly more Christians believe in god (88%) than in unseen beings (81%).

(Some survey respondents may consider belief in god to be part of belief in unseen beings, like deities or spirits.)

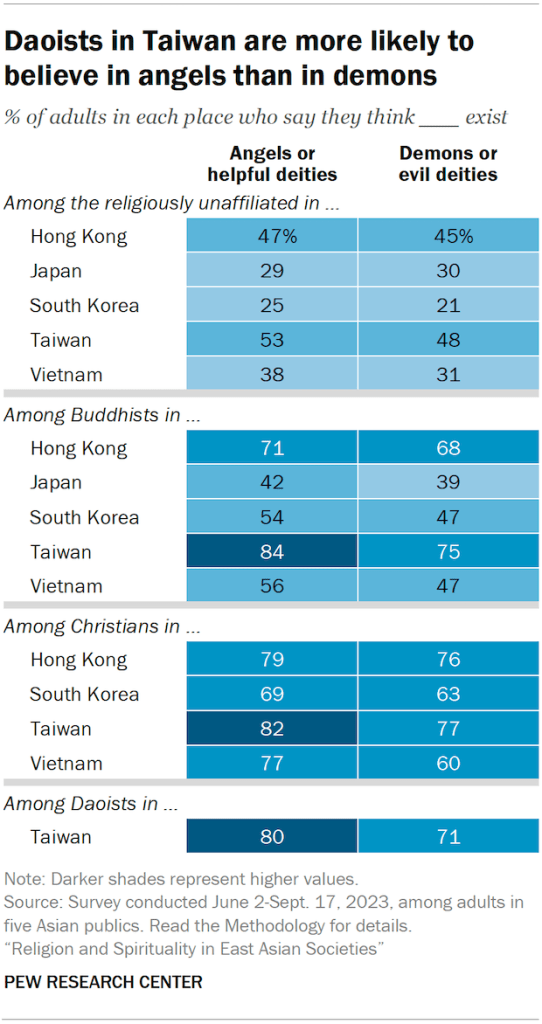

Belief in angels and demons

In addition to asking about belief in god and belief in unseen beings, the survey also asked respondents whether they believe in the existence of “angels or helpful deities” and, separately, in “demons or evil deities.”

Christians typically are more likely than Buddhists to believe in angels and demons. In South Korea, for example, more Christians than Buddhists say both that angels or helpful deities exist (69% vs. 54%) and that demons or evil deities exist (63% vs. 47%).

In all the places surveyed, one-fifth of the religiously unaffiliated or more say both kinds of deities exist.

Women are consistently more likely than men to express belief in angels and demons. For instance, 61% of women in Hong Kong say demons or evil deities exist, compared with 49% of men.

In most places surveyed, people are somewhat more likely to believe in angels or helpful deities than in demons or evil deities. In Vietnam, for example, 49% say angels or helpful deities exist, while 40% say demons or evil deities exist. This pattern mirrors results we have previously found across South and Southeast Asia.

Belief in spirits inhabiting the physical world

Throughout the region, natural forces and certain places have long been considered to have spirits or connections to divinity. To measure this, we asked a series of questions about whether mountains or other parts of nature; houses or other buildings; and objects like crystals or jewels have their own spirits.

Here’s what we found:

- Respondents in all five places are most likely to say that mountains, rivers or trees have their own spirits. Large shares of people in Taiwan (59%), Japan (51%) and Vietnam (47%) express this view.

- Adults in those three places also are more likely than people in South Korea and Hong Kong to say that houses or other buildings have their own spirits.

- Nowhere do more than three-in-ten adults believe that objects like crystals, jewels or stones have spirits.

In general, Buddhists are more likely than Christians and unaffiliated people to say that each category listed has its own spirits.

And the religiously unaffiliated are somewhat more likely than Christians to say that objects like crystals have their own spirits, and to say the same about mountains, rivers or trees. For example, 22% of unaffiliated adults in Vietnam say crystals, jewels or stones have spirits, compared with 14% of Vietnamese Christians.

In most of the places surveyed, women are more likely than men to say that parts of nature, certain objects, and houses or other buildings have their own spirits. The sole outlier is Vietnam, where men and women are about equally likely to hold these beliefs.

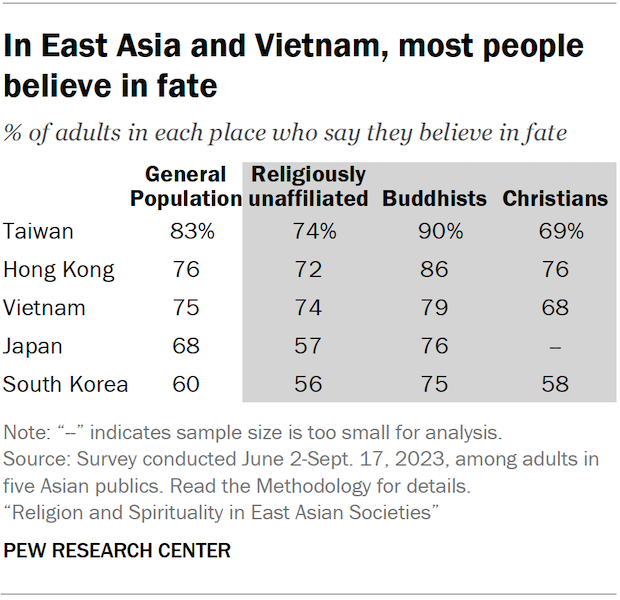

Belief in fate

Majorities of adults across all major religious groups in the five locations say that fate exists. (The survey did not define the word, but fate is often described as the idea that important events, or even the overall course of one’s life, are largely or wholly preordained.)

Buddhists across the region are particularly likely to say that fate exists.

As with other beliefs analyzed in this chapter, belief in fate differs by gender. Across East Asia and Vietnam, women consistently are more likely than men to say fate exists. In South Korea, for instance, 64% of women and 55% of men believe in fate.

Belief in karma

Belief in karma is very common among adults in Taiwan (87%), Hong Kong (76%) and Vietnam (75%), while South Koreans are more evenly split. (The survey did not define “karma,” but it is generally understood to mean that people will reap the benefits of their good deeds and pay the price for their bad deeds, often in future lives.)

Only 16% of Japanese adults say they believe in karma. Nearly three-in-ten Japanese adults declined to answer the question, far more than in the other places surveyed. This may indicate less familiarity with the term.

In most places surveyed, Buddhists are the most likely to say karma exists. While this may be expected – since the concept of karma has deep roots in Buddhist traditions – majorities of Christians in Vietnam, Hong Kong and Taiwan also say karma exists. For example, 71% of Vietnamese Christians believe in karma. Many of the region’s religiously unaffiliated adults, including 78% in Taiwan, also believe in karma.

In Taiwan, belief in karma seems to be very common across the board, including among Daoists (92%) and followers of local or Indigenous religions (97%).

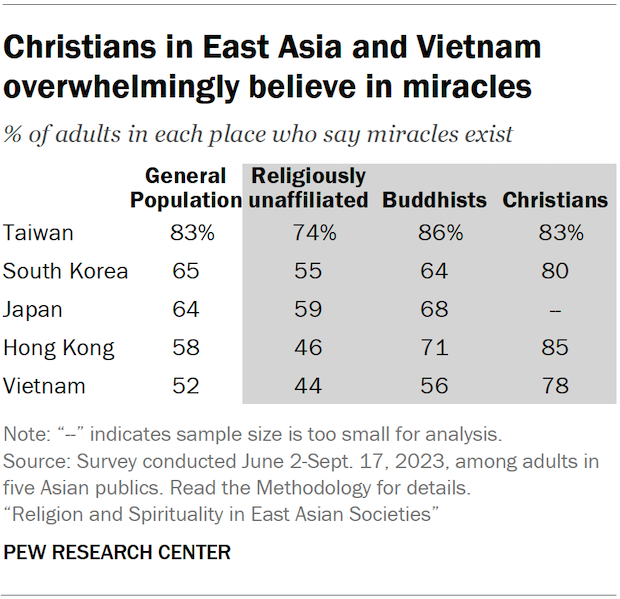

Belief in miracles

In all five places surveyed, at least half of adults say that miracles exist.

This view is especially common in Taiwan, where 83% of adults, including 74% of the religiously unaffiliated, believe in miracles.

In general, Christians are more likely to say that miracles exist, followed by Buddhists and the unaffiliated. In South Korea, for instance, 80% of Christians believe in miracles, compared with 64% of Buddhists and 55% among the religiously unaffiliated.

Respondents with more education are more likely than other adults to believe in miracles. In Hong Kong, 65% of college-educated adults say that miracles exist, compared with 55% of those with less education.