Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

Measuring East Asian and Vietnamese religious and spiritual practices can be as challenging as assessing religious beliefs in the region. The metrics researchers typically use to study religious engagement in other parts of the world are designed primarily for Abrahamic religions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – and fail to capture the breadth and depth of religious observance in the region.

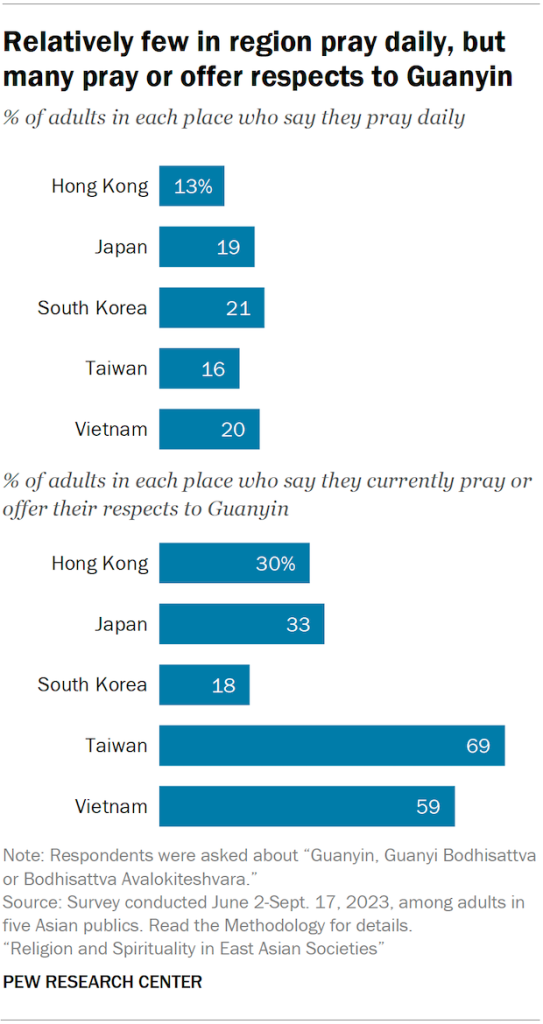

For example, relatively few people in East Asia and Vietnam pray daily – far smaller shares than in South Asia and Southeast Asia.

But many East Asians and Vietnamese say they pray at least occasionally, and substantial shares also say they “pray or offer their respects” to Buddha and other religious figures or deities. Such prayers may be performed at particular times of year, such as during holidays, or as needed to bring luck or help fulfill a wish.

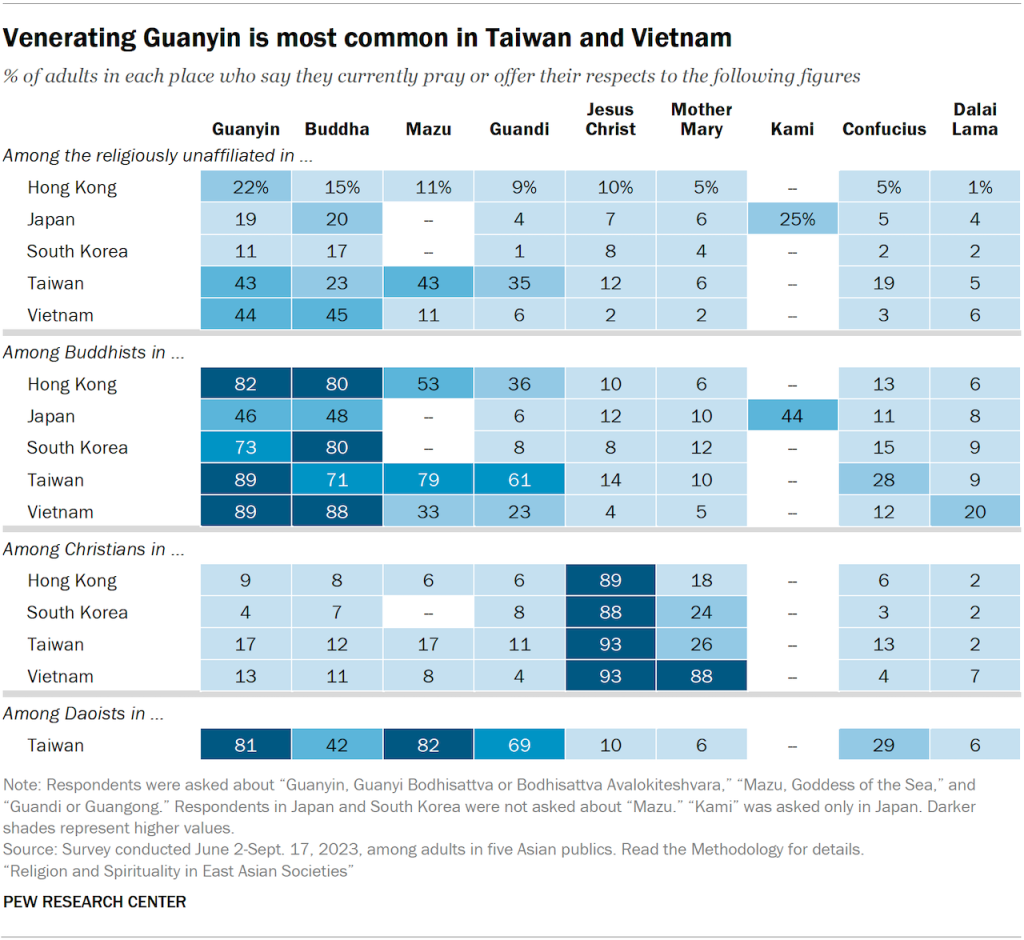

In each location surveyed except Japan, most Buddhists say they offer respects to Guanyin, a folk deity associated with compassion, as well as to Buddha. Almost all Christians say they pray or offer respects to Jesus.

Many people across the region also visit temples, pagodas, shrines, churches or monasteries and keep altars in their homes for purposes that may include venerating ancestors. (For more information on ancestor veneration, funeral rites and family gravesites, go to Chapter 5.)

Home altars are particularly common in Vietnam, where nearly all adults have one. In the other places surveyed, no more than half of adults say they have a home altar, including just 6% of South Koreans. On the other hand, 59% of South Koreans say they meditate – by far the highest share in the five places surveyed.

As we found in previous surveys in South and Southeast Asia, Buddhists in this survey are generally more likely than Christians to have a home altar, while Christians are more likely to pray daily.

Religiously unaffiliated adults tend to pray or offer respects to Buddha (or Jesus) at much lower rates than Buddhists (or Christians) do. Still, more than four-in-ten religiously unaffiliated people in Vietnam and Taiwan pray or offer their respects to Guanyin, and more than half say they generally go to temples or pagodas.

Across the region, people with less education are, in general, more likely than adults with higher levels of education to engage in many of these spiritual and religious practices. However, people with less education are less likely to meditate or have their fortunes told.

Venerating religious figures and deities

Most Buddhists in each of the locations surveyed, except Japan, say they pray or offer respects to Buddha. Similarly, roughly nine-in-ten Christians or more in each society surveyed except Japan –where our sample of Christians is too small to be analyzed separately – say they pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ.

The survey did not ask respondents whether they consider either figure – Buddha or Jesus – to be a deity.8

“Offering respects” is commonly understood in the region as an act of worship or veneration. It can take a variety of forms, such as burning incense, offering food or drink, or making wishes to a deity. It is often expressed through gestures like bowing one’s head or putting one’s hands together.

Guanyin – a folk deity associated with compassion and mercy who helps humans along the path to enlightenment – is also revered widely. Guanyin is an East Asian representation of the Buddhist bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, and in most places across the region about as many Buddhists pray or offer their respects to Guanyin as to Buddha. In Taiwan, Buddhists are more likely to pray or offer respects to Guanyin (89%) than to Buddha (71%).

Over half of adults in Taiwan also pray or offer respects to Guandi, also known as Guangong, traditionally worshiped as a god of war in many parts of East Asia.

Respondents in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam were also asked about Mazu, a Chinese goddess of the sea, whose worship spread over centuries along East and Southeast Asian coastlines. Two-thirds of Taiwanese adults say they pray or offer their respects to Mazu, including about eight-in-ten Taiwanese Buddhists and Daoists (also spelled Taoists), and nearly nine-in-ten followers of Indigenous religions who do so. Reverence for Mazu is less common elsewhere, although around half of Buddhists in Hong Kong and one-third in Vietnam say they pray or offer their respects to her.

Even among the region’s religiously unaffiliated people, substantial shares offer respects to certain figures. For example, roughly four-in-ten unaffiliated adults in Taiwan and Vietnam say they pray to Guanyin, as do about one-in-five of the unaffiliated in Hong Kong and Japan. In Taiwan, a third of the religiously unaffiliated or more pray or offer their respects to Mazu and Guandi.

The survey also asked about paying respects to Confucius, the ancient Chinese sage whose teachings form the core of Confucianism. While many experts do not consider Confucianism to be a religion, its teachings on divine power, benevolence, loyalty and respect – especially for one’s parents, ancestors and social superiors – permeate East Asian spiritual traditions.

Praying or offering respects to Confucius is most common in Taiwan. For instance, roughly one-fifth of the island’s religiously unaffiliated adults say they do this, compared with 5% or fewer of the unaffiliated elsewhere in the region. And Taiwan’s Buddhists are about twice as likely as the other Buddhists surveyed to pray or offer respects to Confucius.

While Christians are more likely than other groups to pray or offer their respects to Mother Mary – believed by Christians to be the mother of Jesus – only in Vietnam do most Christians do this. (This could be related to the prevalence of Catholics in Vietnam’s Christian population.)

In Japan (and only in Japan), we asked people about kami. In the Shinto tradition, kami are deities or spirits often associated with particular parts of the natural landscape, such as a mountain or forest; the deified spirits of some human beings also are considered kami. Among Japanese Buddhists, 44% say they pray or offer their respects to kami, as do 25% of Japan’s religiously unaffiliated adults.

Rates of prayer

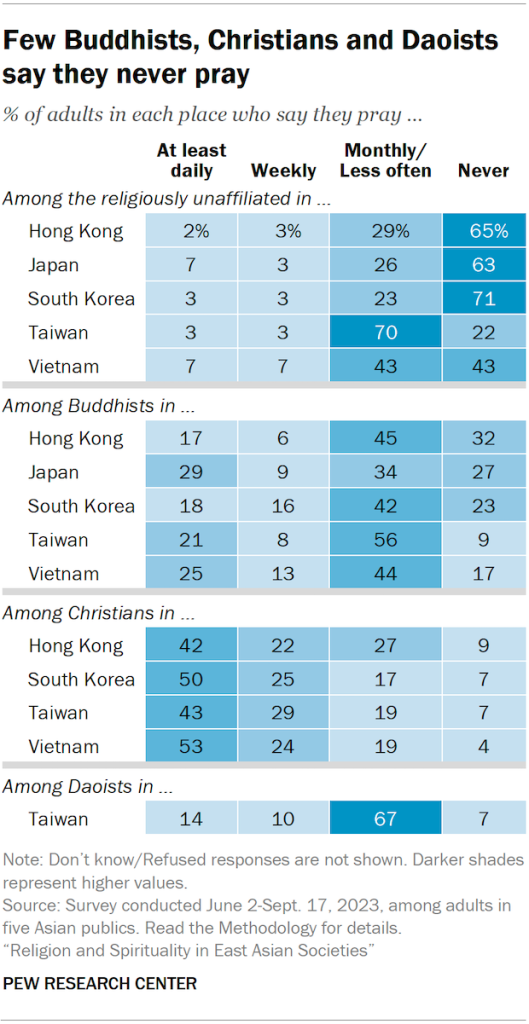

We also asked respondents how often they pray, if at all. Frequent prayer is not common in the region. Across the five places surveyed, no more than 21% of people say they pray daily.

However, half or more in each place say they pray at least sometimes, including 85% in Taiwan and 71% in Vietnam.

Of the major religious groups, Christians are most likely to pray at least once a day. About half of Christians in Vietnam and South Korea say they do so.

While Buddhists are much less likely than Christians to pray daily, most do pray at least occasionally.

Far fewer of the region’s religiously unaffiliated adults pray regularly. In South Korea, Hong Kong and Japan, most of the unaffiliated say they never pray.

Throughout the region, women are more likely than men to say they pray at least once each day. For example, 24% of Vietnamese women report that they pray daily, compared with 15% of Vietnamese men.

Daily prayer around the world

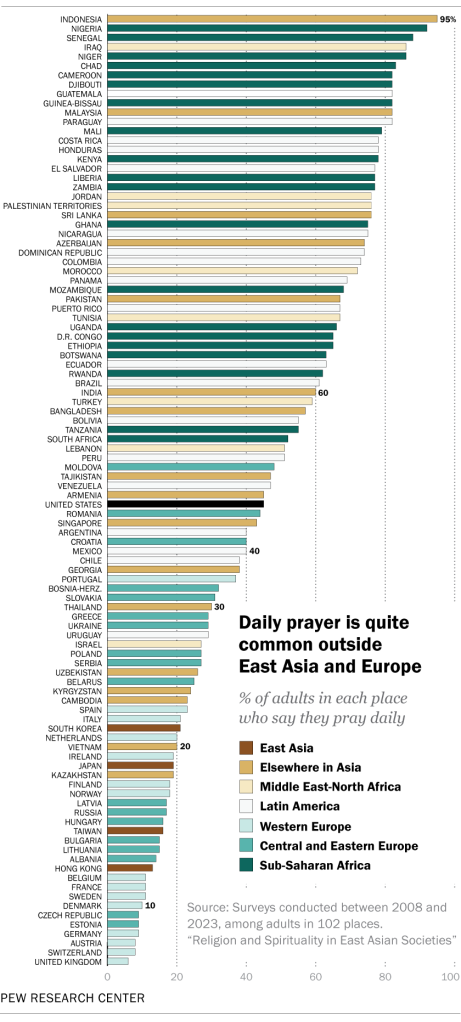

In East Asia and Vietnam, no more than about two-in-ten people say they pray daily. Many parts of Europe have similarly low rates of daily prayer, according to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 102 countries and territories around the world since 2008.9

In South and Southeast Asia, however, adults are generally more likely to pray at least once a day. For example, six-in-ten Indians say they do this, as do almost all Indonesians.

People in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America also are more likely than people in East Asia and Vietnam to say they pray daily.

U.S. adults are roughly twice as likely as adults in Japan, South Korea and Vietnam to report that they pray daily. In our international research, the United States is unusual because it is both a wealthy country – as measured by gross domestic product per capita – and has a large percentage of people who pray daily.

(For information on when we conducted surveys in various countries and territories, go to Appendix A.)

Visiting spiritual and religious sites

East Asia and Vietnam have a wide variety of sacred sites, ranging from shrines and pagodas to monasteries and places of scenic beauty, such as sacred woods. People visit these sites for many reasons – to make offerings, meditate, pray or just look around as tourists.

The survey asked respondents whether they “generally go to” a few kinds of religious sites: temples or pagodas; shrines; churches; and monasteries or places for meditation.

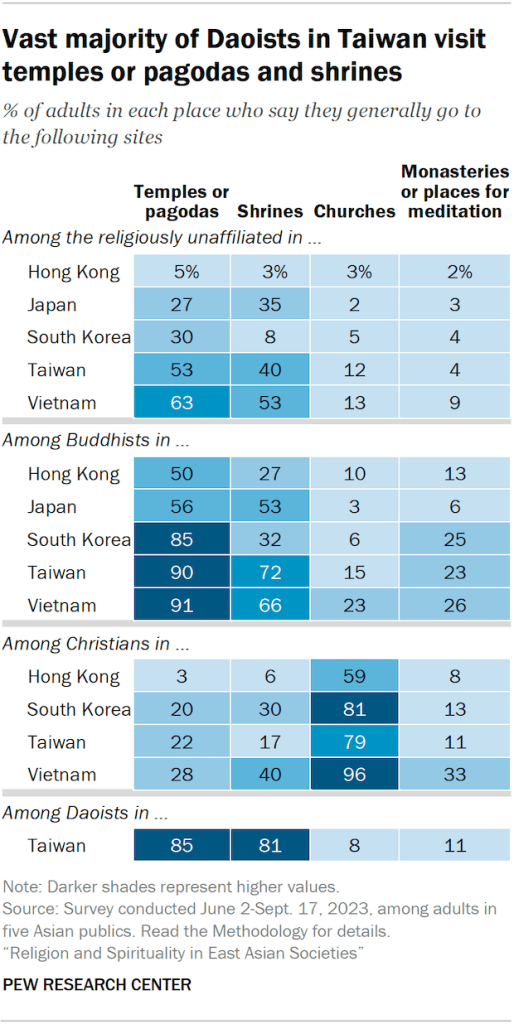

Most Buddhists say they generally go to temples or pagodas, including overwhelming majorities in Vietnam (91%), Taiwan (90%) and South Korea (85%). Many Buddhists across the region also say they visit shrines. And about a quarter of Buddhists in Vietnam, South Korea and Taiwan go to monasteries or places for meditation.

Half of the religiously unaffiliated or more in Vietnam and Taiwan say they go to temples or pagodas. A third of the religiously unaffiliated or more in Vietnam, Taiwan and Japan also say they generally visit shrines.

Most Christians surveyed say they generally go to church, including nearly all Christians in Vietnam (96%). Substantial shares of Vietnamese Christians also say they go to other religious or spiritual sites, including shrines (40%), monasteries or places for meditation (33%) and temples or pagodas (28%).

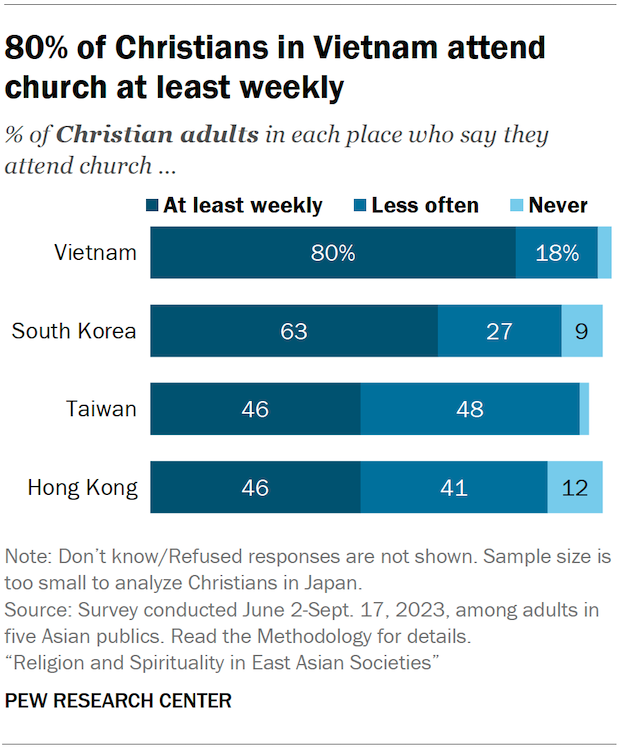

We also asked Christians (and only Christians) how often they attend church services. Majorities of Christians in Vietnam and South Korea say they attend church at least weekly. In both Hong Kong and Taiwan, 46% of Christians report that they attend services once per week or more.

(In Japan, the number of Christians surveyed is too small to allow their answers to be analyzed and reported separately.)

Home altars

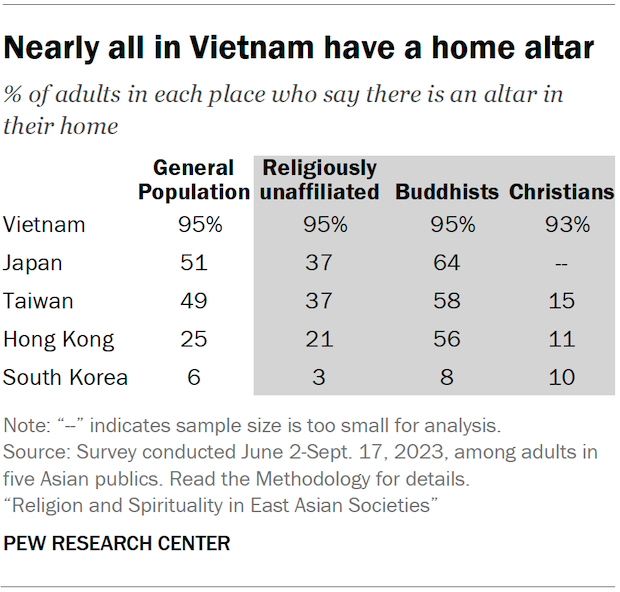

Nearly all adults in Vietnam have an altar in their home (95%), compared with about half of adults in Japan and Taiwan. Far fewer in Hong Kong (25%) and South Korea (6%) say their home contains an altar.

In Vietnam, equally large shares of Buddhists, Christians and even religiously unaffiliated people say they have an altar in their home. By contrast, no more than 10% of any of these groups in South Korea say they have one.

(According to a 2023 survey we conducted in the U.S., Vietnamese Americans are also more likely than most other Asian Americans – including those with Korean and Japanese ancestry – to have an altar, shrine or religious symbols used for worship at home.)

Majorities of Buddhists in each of the places surveyed, except South Korea, have home altars. Except in Vietnam, altars are less popular among the unaffiliated and are rarely found in Christian homes.

In general, adults with less education are more likely than those with more education to say they have an altar in their home. The exception, again, is Vietnam, where adults with more education are slightly more likely than others to have a home altar, though both groups overwhelmingly say they do (97% vs. 93%).

Meditation

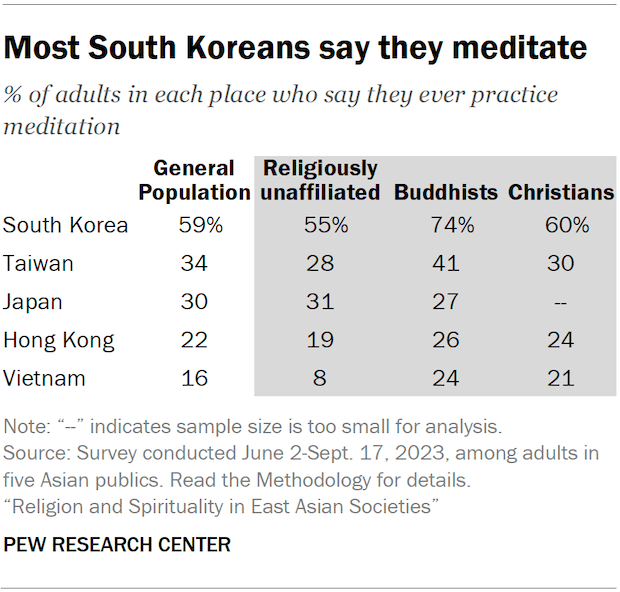

Meditation is most common in South Korea, where a majority of adults say they practice it. In the other places surveyed, the share of people who ever meditate ranges from 16% in Vietnam to 34% in Taiwan.

In general, Buddhists are more likely than unaffiliated people to say they meditate. In Taiwan, for example, 41% of Buddhists and 28% of the unaffiliated say they meditate.

The share of Christians who ever meditate ranges from 21% in Vietnam to 60% in South Korea.

Respondents with higher levels of education tend to be more likely than those with less education to meditate. For instance, 42% of Taiwanese who have a degree beyond high school say they meditate, compared with 28% of those with less education.

Reflecting on life and the universe

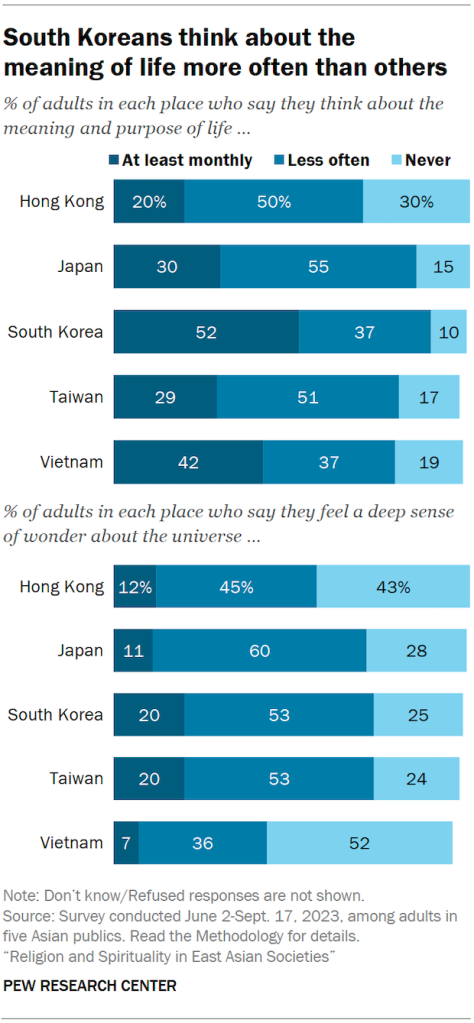

We asked two questions about respondents’ personal reflections: How often do they think about the meaning and purpose of life, and how often do they feel a deep sense of wonder about the universe?

Majorities across the region say they at least sometimes think about the meaning and purpose of life. The share who report that they think about this at least monthly ranges from 20% in Hong Kong to 52% in South Korea.

Feeling a deep sense of wonder about the universe seems to be less common. In no place surveyed do more than 20% of adults say they feel such wonder at least monthly. In Vietnam, 52% say they never have this experience.

Christians are generally more likely than Buddhists or the religiously unaffiliated to say they think about the meaning of life or feel a deep sense of wonder about the universe. In South Korea, for example, 62% of Christians say they think about the meaning of life at least monthly, compared with 50% of Buddhists and 47% of the unaffiliated.

Fortunetelling

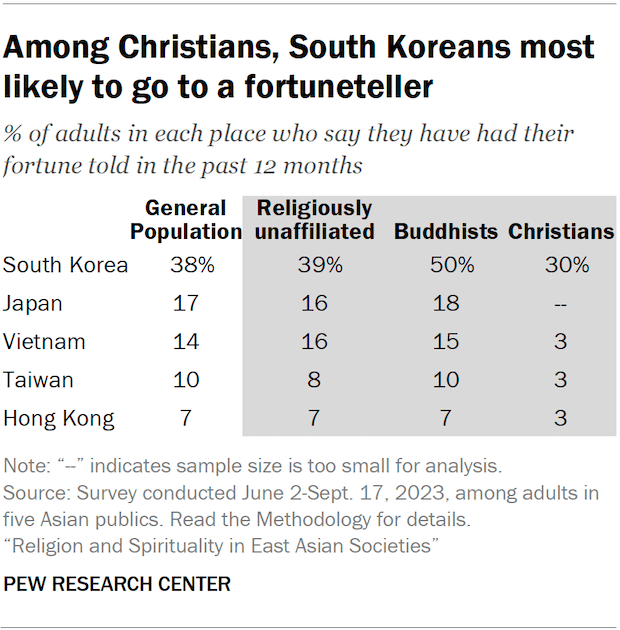

East Asian societies have long-standing traditions of fortunetelling with roots in ancient shamanist practices.

But relatively few people in the five places surveyed say they consulted a fortuneteller in the last year. The practice is most common in South Korea, where 38% say they had their fortune told in the past 12 months.

Christians tend to be less likely than Buddhists or the religiously unaffiliated to consult fortunetellers. Only 3% of Christians in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam say they have had their fortunes told in the last year.

In all places surveyed, younger adults are more likely than older adults to go to a fortuneteller. For instance, 19% of Taiwanese ages 18 to 34 say they had their fortune told in the past 12 months, compared with 6% of older adults.

Women are also more likely than men to say they consulted a fortuneteller in the past year.