For this report, we surveyed 10,390 adults across East Asia and neighboring Vietnam. Local interviewers administered the survey in seven languages from June to September 2023. Interviews were conducted over the phone in four places: Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. In Vietnam, interviews took place face-to-face.

This survey, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, a broader effort by Pew Research Center to study religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; Israel; Central and Eastern Europe; Western Europe; India; South and Southeast Asia; and the United States.

When we designed the survey, we took several steps to help ensure that the questions would be culturally appropriate and that respondents would understand their intended meaning. We consulted with an advisory panel of academic experts on religion in Asia. We conducted cognitive interviews in Japan and Taiwan. (In cognitive interviews, respondents are asked to read a question aloud, to answer it, and to discuss their thinking.) The full survey questionnaire also was pretested in all five locations prior to fieldwork.

The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into six other languages. Professional linguists with native proficiency independently checked the translations. In questions about belief in “god,” translators were instructed to choose the most generic possible word for god in each language and to avoid terms that refer exclusively to the god(s) or goddess(es) of any particular religion.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design. Data was weighted to account for different probabilities of selection and to align with demographic benchmarks for the adult population. This ensures that the surveys are representative of the broader public in terms of age, gender and education.

For more information, refer to the report’s Methodology section and the full survey questionnaire.

Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

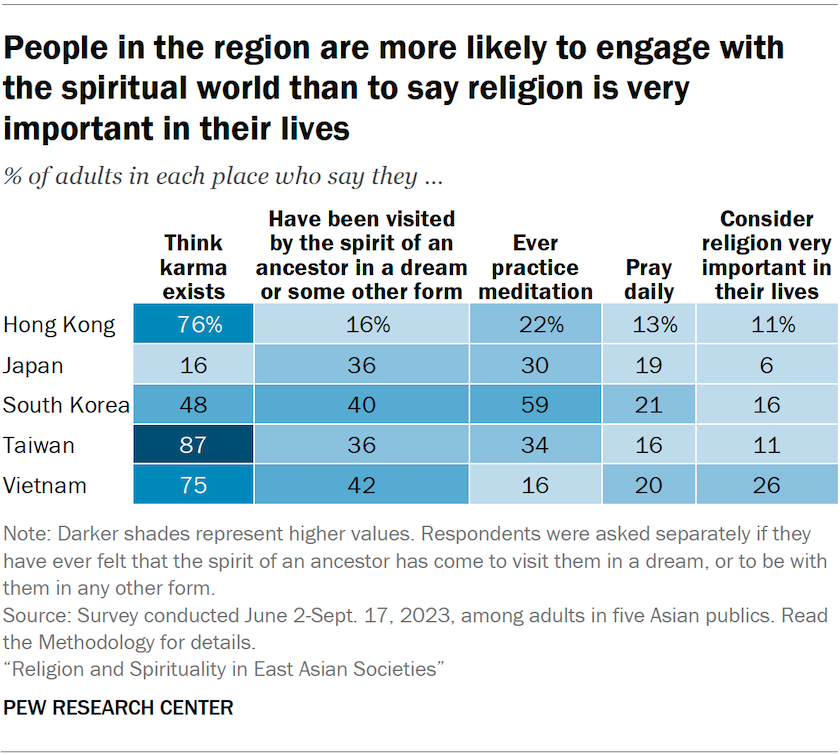

By some measures, East Asia seems like one of the least religious regions in the world. Relatively few East Asian adults pray daily or say religion is very important in their lives. And rates of disaffiliation – people leaving religion – are among the highest in the world, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of more than 10,000 adults in East Asia and neighboring Vietnam.

Yet, the survey also finds that many people across the region continue to hold religious or spiritual beliefs and to engage in traditional rituals.

- A majority of adults surveyed in Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam say they believe in god or unseen beings.

- Many also participate in ancestor veneration rituals with religious underpinnings. In Japan, for instance, 70% report that they have offered food, water or drinks to honor or care for their ancestors in the past 12 months. In Vietnam, 86% have performed this ritual in the last year.

- Praying or offering respects to religious figures or deities is fairly common. For example, 30% of adults in Hong Kong say they pray or offer their respects to Guanyin, a deity associated with compassion, and 46% in Taiwan pray or offer respects to Buddha.

Translations

- Japanese: Main findings | Overview

- Korean: Main findings | Overview

- Simplified Chinese: Main findings | Overview

- Traditional Chinese: Main findings | Overview

- Vietnamese: Main findings | Overview

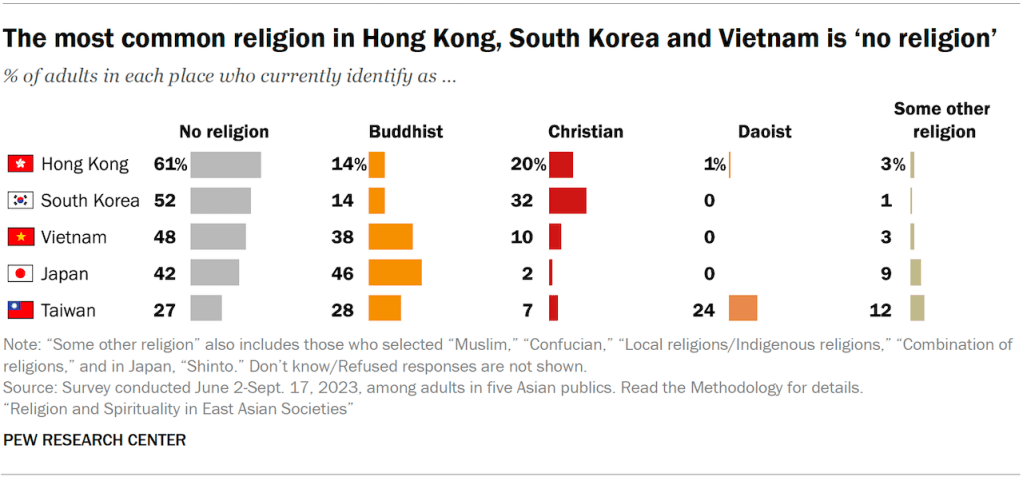

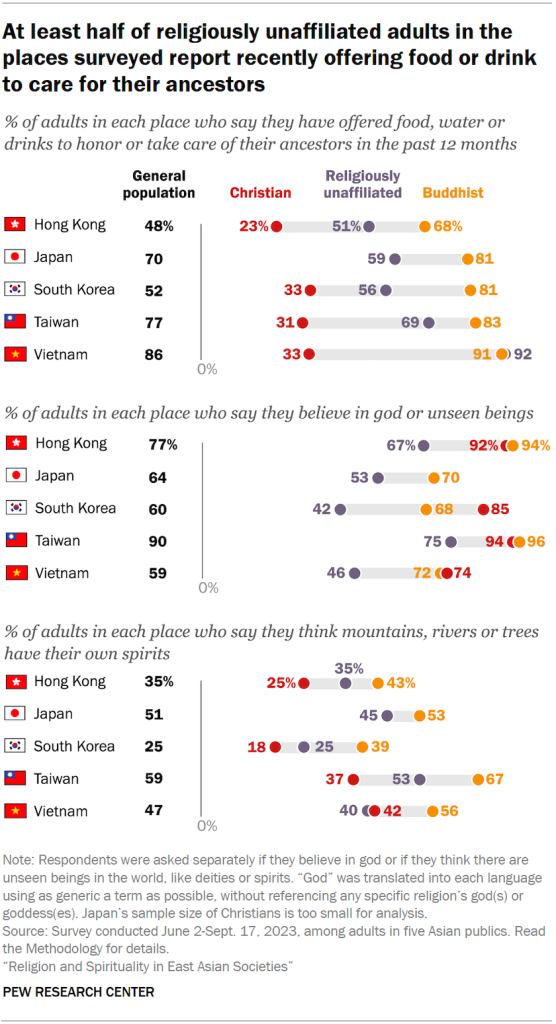

Large numbers of adults across the region – ranging from 27% in Taiwan to 61% in Hong Kong – say they have “no religion.” But even among these religiously unaffiliated people, half or more leave offerings for deceased ancestors; at least four-in-ten believe in god or unseen beings; and a quarter or more say that mountains, rivers or trees have spirits.

In short, when we measure religion in these societies by what people believe and do, rather than whether they say they have a religion, the region is more religiously vibrant than it might initially seem.

Collecting data on religion in East Asia is a complex challenge. The concept of religion was imported to the region by scholars only about a century ago, and common translations of “religion” (such as zongjiao in Chinese, shūkyō in Japanese and jonggyo in Korean) often are understood to refer to organized, hierarchical forms of religion, such as Christianity or new religious movements – not to traditional Asian forms of spirituality.

The survey included a few questions that have long been used to measure religious observance in other parts of the world, such as how important religion is in people’s lives. But this report places more emphasis on new questions designed to measure beliefs and practices that are relatively common in Asian societies, including: ancestor veneration; the presence of spirits in the natural world; offering respects to deities and religious figures; beliefs about life after death; and personal connections to religion aside from identity.

The report is based on a major, regional survey of 10,390 adults in four East Asian societies (Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan) and neighboring Vietnam. The survey was conducted in seven languages from June 2 to Sept. 17, 2023. It builds on studies that Pew Research Center previously has published on religion in China, India, and South and Southeast Asia.

More highlights in this Overview: Religious switching in the region | Religious switching in East Asia compared with the rest of the world | Common beliefs and practices | How former Buddhists in East Asia compare with lifelong Buddhists | Other key findings in this report

The rest of this report covers:

Religious switching in the region

Most people surveyed either have no religious affiliation or identify as Buddhist. Moreover, in South Korea and Hong Kong, substantial shares of adults identify as Christian, and Taiwan has a sizable number of Daoists (also spelled Taoists).1

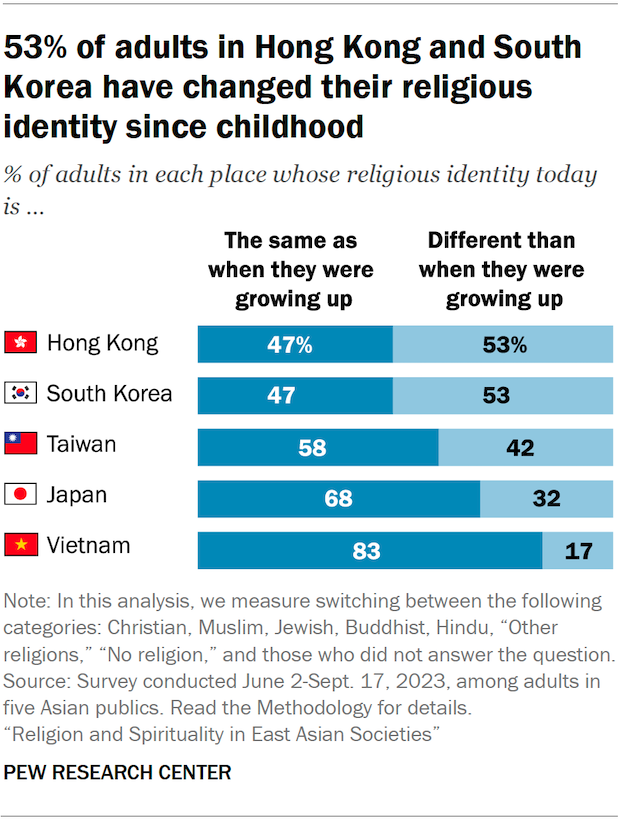

But religious identification in the region is undergoing a remarkable amount of change. Many people say they were raised with a different religious identity than the one they now claim.

The shares who have switched away from their religious upbringing to some other religion – or to no religion – range from 17% of adults in Vietnam to 53% each in Hong Kong and South Korea.

(We use the term “switch” rather than “convert” to indicate that the movement goes in all directions and does not necessarily involve any formal rite or ceremony.)

Rates of religious switching are based on movement between major world religious traditions, not switching within a tradition. For instance, switching between Christianity and Buddhism is picked up by these measures, but switching between Catholicism and Protestantism or between different branches of Islam is not.

We also count someone who has moved from a specific religion to no religious identity – or vice versa –as having switched.

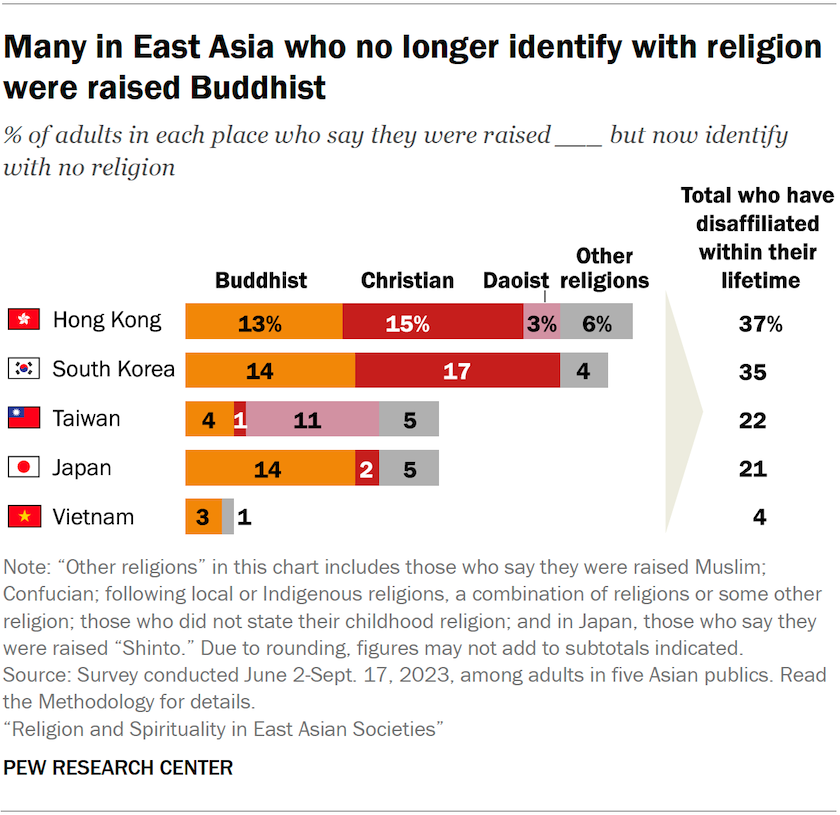

The bulk of the switching is disaffiliation: Many East Asians say they were raised in a religion during their childhood and now identify with none. (This is much less common in neighboring Vietnam.)

The departures are mostly from Buddhism, Christianity and Daoism. For instance, 15% of adults in Hong Kong say they were raised as Christians but now have no religion. And 14% of South Korean and Japanese adults report that they were brought up as Buddhists but no longer identify with any religion.

However, the high rates of religious switching do not arise exclusively from people abandoning religion. Roughly one-in-ten adults in South Korea (12%) and Hong Kong (9%) currently identify as Christian but were raised in a different religious tradition, such as Buddhism, or were raised with no religious identity.

Similarly, 11% of adults in Taiwan and 10% in Vietnam were raised outside Buddhism but now identify as Buddhist.

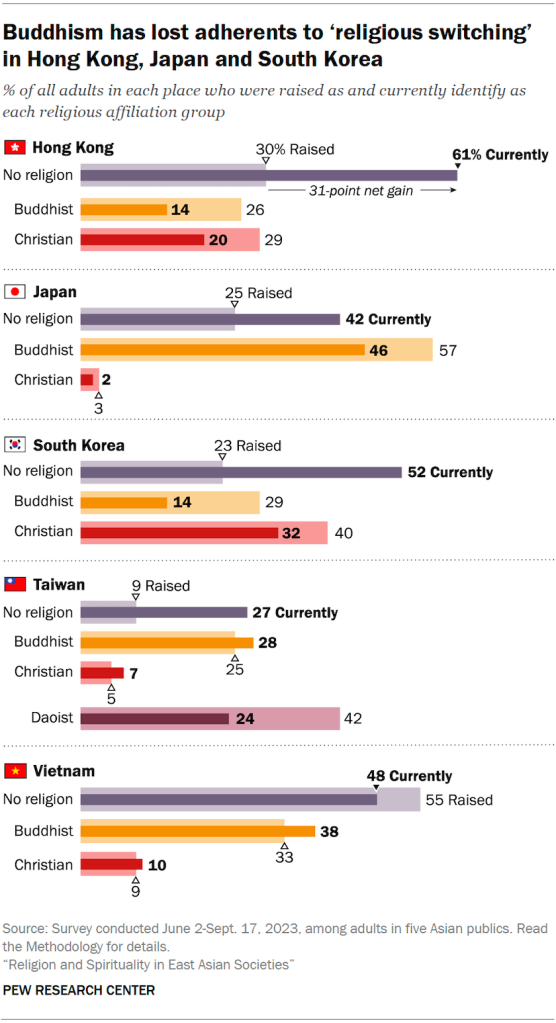

Still, on balance, the religiously unaffiliated population has had a net gain from switching in four of the places surveyed, drawing from every other religious group in our analysis.

In Hong Kong, for example, 30% of adults say they were raised without a religion, while 61% currently identify as religiously unaffiliated – a gain of 31 percentage points.

Vietnam is the only place surveyed where the unaffiliated population has experienced a net loss due to religious switching: 55% of Vietnamese adults say they were raised without a religion, while 48% identify with no religion today.

Meanwhile, Buddhists have experienced net losses from religious switching in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. For instance, 29% of adults in South Korea say they were raised Buddhist, but 14% say they are currently Buddhist – a 15-point decline.

On the other hand, Buddhists have seen slight increases due to religious switching in Taiwan and Vietnam.

(Read more about religious switching in Chapter 1.)

Religious switching in East Asia compared with the rest of the world

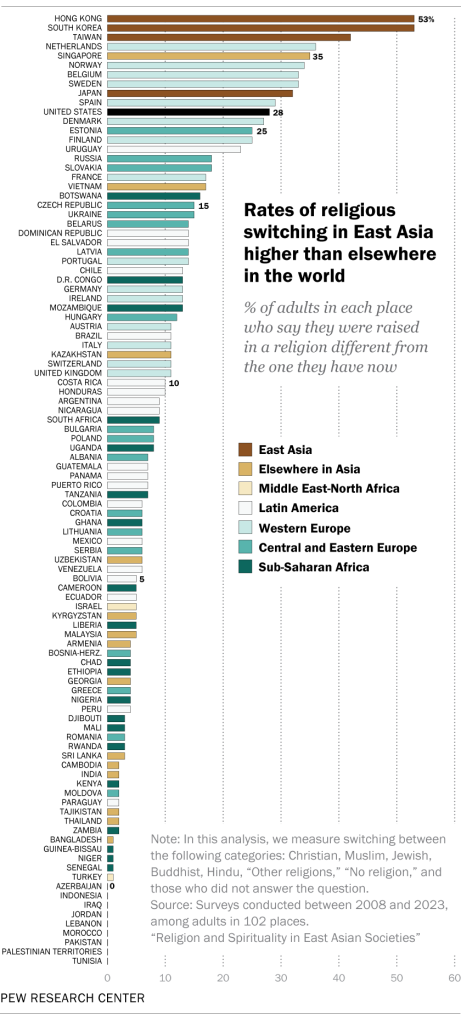

East Asian rates of religious switching (from 32% in Japan to 53% in Hong Kong and South Korea) are higher than Pew Research Center has measured in many other places.2 For example, in our previous surveys of religion across Asia since 2019 – including in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Thailand – only Singapore’s rate of religious switching (35%) approaches the rates seen in East Asian societies.

Even in our 2017 survey of 15 countries in Western Europe – a region where decades of disaffiliation have led to sharp growth in the number of religiously unaffiliated people – we did not find any country in which the switching rate exceeded 40%. (The highest was 36%, in the Netherlands.)

And in the United States, 28% of adults no longer identify with the religious tradition in which they were raised, according to data we collected in summer 2023.

Religious switching is far less common in other parts of the world, such as Latin America and the Middle East-North Africa region.3

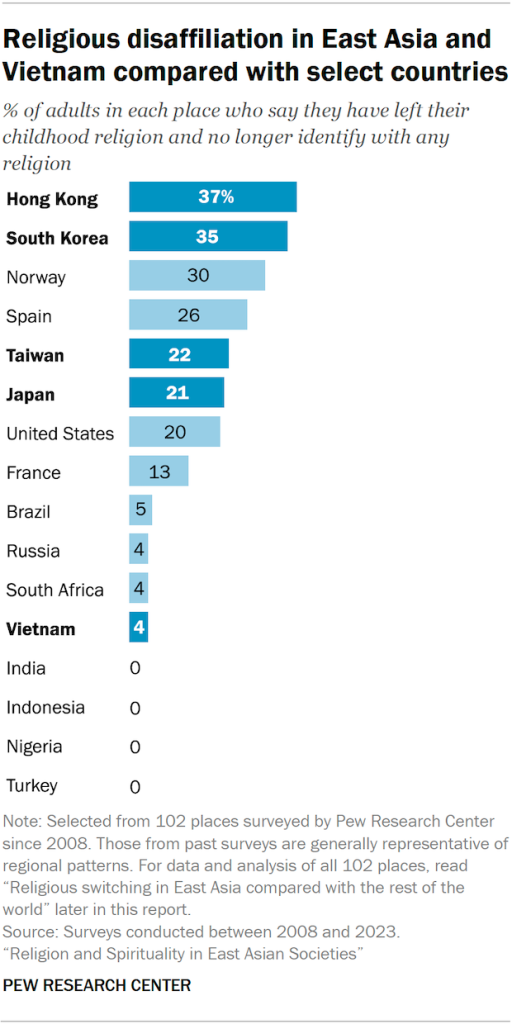

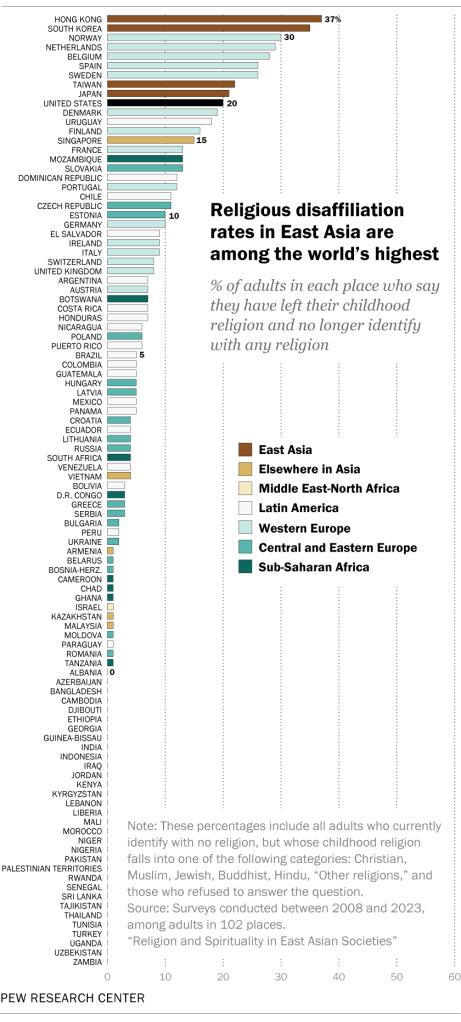

We also analyzed the data we have collected around the world since 2008 to see how disaffiliation rates in East Asia and Vietnam compare with other places.

Hong Kong (37%) and South Korea (35%) have the world’s highest shares of adults who say they were raised in a religion but who no longer identify with one. They are followed by several Western European countries, including Norway (30%), the Netherlands (29%) and Belgium (28%).

Also high on the list are two other East Asian societies: Taiwan (22%) and Japan (21%).

In the vast majority of places we have surveyed over the years – including most locations surveyed in Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East-North Africa region and much of sub-Saharan Africa – roughly 5% of adults or fewer say they were raised with a religion but now have none. Of the five places we surveyed for this report, only Vietnam has a disaffiliation rate that low (4%).

(For information on when we conducted surveys in 102 countries and territories, go to Appendix A.)

Common beliefs and practices

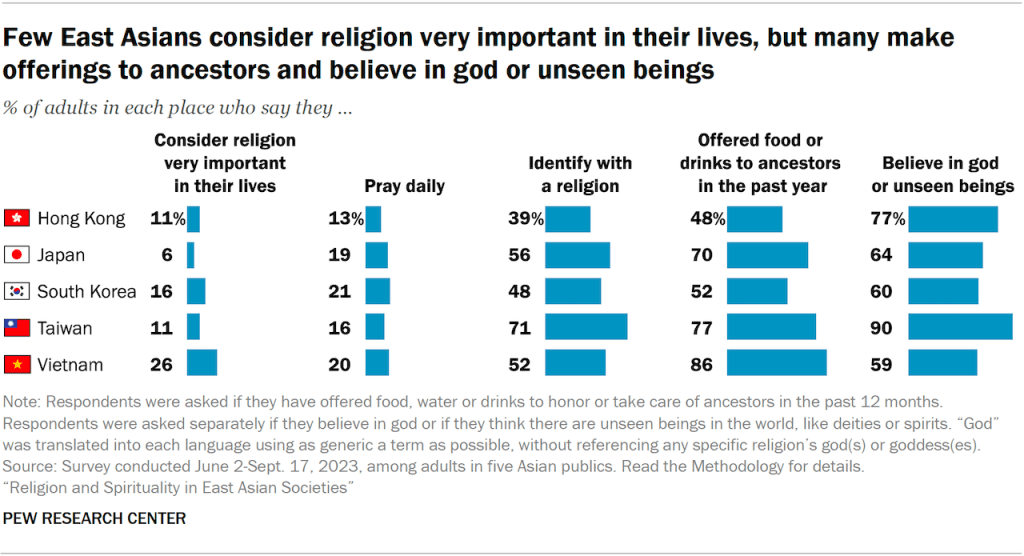

Pew Research Center’s religion surveys often ask, “How important is religion in your life?” We use this question as one way, among many, to measure the role that religion plays in people’s lives across geographies and over time.

Given the comparatively low rates of religious affiliation in some parts of East Asia, as well as the complexity of translating the word “religion” into some Asian languages, it is perhaps not surprising that relatively few people in the region say religion is “very important” to them.

In the five places we surveyed, no more than 26% of adults say religion is very important in their lives, including just 6% in Japan.4 In other parts of the world – including some neighboring Asian countries – surveys have often found much higher figures.5

However, many people who do not consider religion to be very important in their lives nevertheless engage in a variety of religious practices and hold a range of spiritual beliefs.

In Taiwan, for example, just 11% of adults say religion is very important to them, but 87% believe in karma, 36% say they have ever been visited by the spirit of an ancestor, and 34% say they ever practice meditation.

The spirits of ancestors have long been a focus of rituals in East Asia and neighboring Vietnam, and ancestor veneration remains widely practiced. Roughly half of adults or more in all the places we surveyed say they have recently offered food, water or drinks to honor or take care of their ancestors. This practice is common among Buddhists and people who do not identify with a religion.

One particularly striking example: 92% of religiously unaffiliated Vietnamese adults say they have made an offering to ancestors in the past year.

These connections with deceased relatives are not always seen as one-way. In every place but Hong Kong, about four-in-ten adults say they have been visited by the spirit of an ancestor in a dream or some other form.

Most adults surveyed in all five places say they believe in god or unseen beings, like deities or spirits. While religiously unaffiliated adults believe in god or unseen beings at lower rates than Christians and Buddhists do, at least four-in-ten unaffiliated adults in each place express these beliefs. In Taiwan, three-quarters of religiously unaffiliated people say they believe in god or unseen beings.

A sizable share of adults also view nature as a realm of invisible spirits. In Taiwan, Japan and Vietnam, about half of adults or more say they believe that mountains, rivers or trees have their own spirits.

How former Buddhists in East Asia compare with lifelong Buddhists

As we have seen, there is a lot of religious disaffiliation in East Asia: 37% of adults in Hong Kong, 35% in South Korea, 22% in Taiwan and 21% in Japan say they were raised in a religion such as Buddhism, Christianity or Daoism during childhood but no longer identify with any religion today. (By comparison, only 4% of Vietnamese adults have disaffiliated.)

At the same time, a lot of people who say they have “no religion” nevertheless express some religious beliefs and say they engage in some traditional spiritual behaviors.

This raises the question: How meaningful is religious affiliation in Asia? Do the religious labels even matter?

The short answer is yes – the way people describe themselves does have meaning. Consider, for example, three categories of East Asians:

- Lifelong Buddhists (people who say they were raised as Buddhists and still consider themselves Buddhists)

- Former Buddhists, now unaffiliated (people who say they were raised as Buddhists but no longer identify with any religion)

- Lifelong unaffiliated (people who say they were raised in no religion and still don’t identify with one)

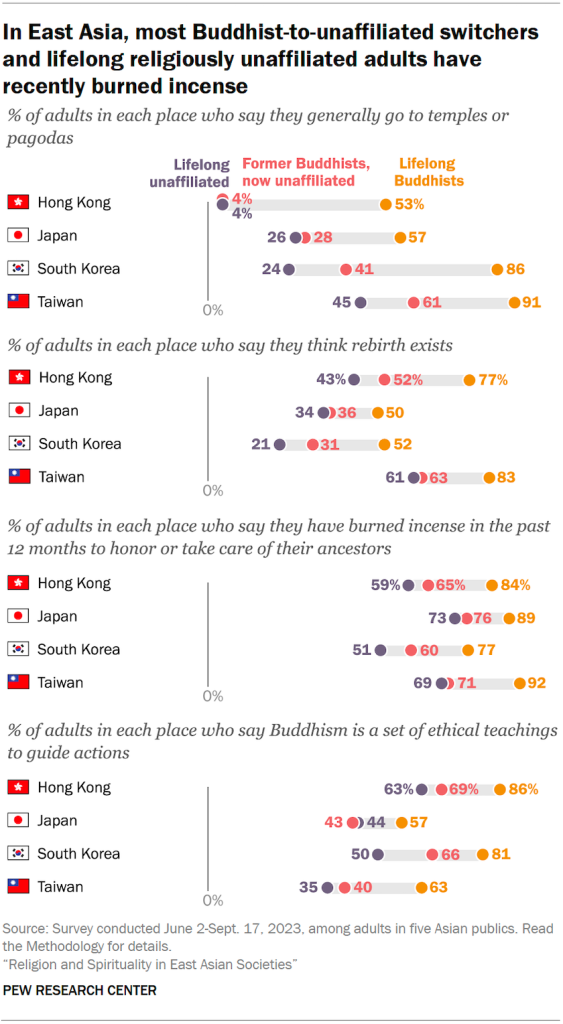

There are enough people in all three categories in the four East Asian societies we surveyed – Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan – to allow for detailed analysis of each group. In all these places, lifelong Buddhists consistently report engaging in religious practices and holding religious beliefs at significantly higher rates than former Buddhists do. But there also may be some residual effect of a Buddhist childhood on the former Buddhists, who, on average, are somewhat more religious than the lifelong unaffiliated.

For instance, lifelong Buddhists in Taiwan are 30 percentage points more likely than former Buddhists to say they generally go to temples or pagodas (91% vs. 61%). The former Buddhists, in turn, are 16 points more likely to visit temples or pagodas than are Taiwanese who have been unaffiliated all their lives (61% vs. 45%).

Similar patterns appear on survey questions about venerating ancestors. While most people in all three categories say they have burned incense in the past 12 months to honor or take care of their ancestors, this activity is most common among lifelong Buddhists. In Hong Kong, 84% of lifelong Buddhists have burned incense for ancestors in the past year, while 65% of former Buddhists and 59% of the lifelong unaffiliated say they have done so.

Moreover, in their concept of what Buddhism is, former Buddhists generally are closer to the lifelong unaffiliated than to lifelong Buddhists. A majority of Japan’s lifelong Buddhists (57%) view Buddhism as “a set of ethical teachings to guide actions,” while smaller shares of former Buddhists (43%) and the lifelong unaffiliated (44%) say this.

In short, how people describe their present religious affiliation and their childhood affiliation tends to correspond with their level of religious belief and practice.

Other key findings in this report

- At least one-fifth of adults in each of the four East Asian societies surveyed, as well as 79% of adults in neighboring Vietnam, report feeling that the spirit of an ancestor has come to their aid at some point in their lives. (Chapter 5 has more information about interactions with ancestors.)

- Most people surveyed across the region say they feel a personal connection to the “way of life” of at least one religious belief or philosophy, even if it’s not exactly the same as their current religious identity. For instance, 34% of South Korean Christians say they feel a personal connection to the Buddhist way of life, and 26% of Buddhists in South Korea feel a connection to the Christian way of life. (Chapter 2 discusses religion as a way of life and people’s affinity for multiple traditions.)

- Large shares of adults in all religious groups say Buddhism is “a set of ethical teachings to guide actions,” “a culture one is part of” and “a religion one chooses to follow.” (Chapter 2 has more detail on how the survey respondents define Buddhism, as well as some beliefs and practices that Buddhists view as crucial to being “truly” Buddhist.)

- People across the region – Christians in particular – generally view religion as a positive force in their societies. (Chapter 6 offers more information on the intersection of religion and society.)