Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

While many people in East Asia and Vietnam do not formally identify with a religion, most say they feel a personal connection to the “way of life” of at least one religious tradition or spiritual philosophy.

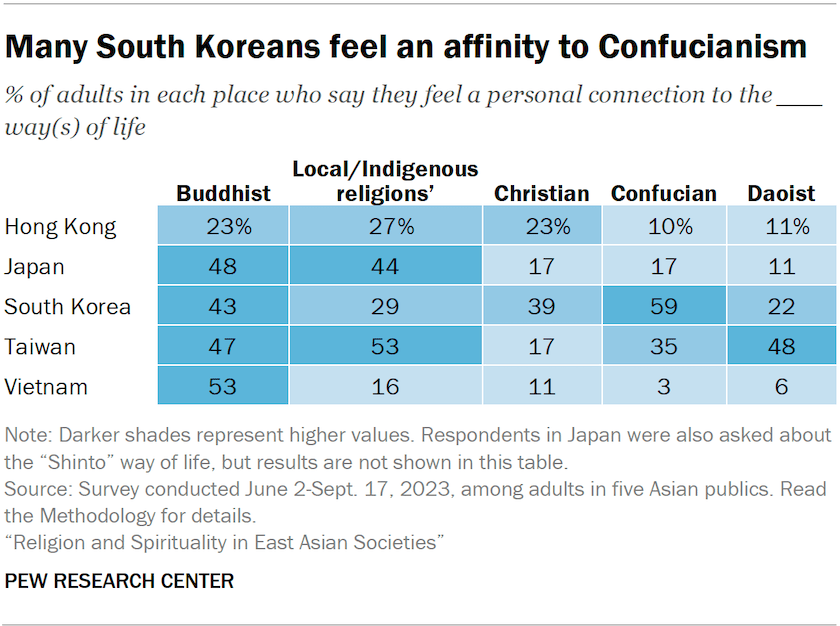

Most commonly, people in the region – including the religiously unaffiliated – feel personal connections to Buddhism and local or Indigenous religions. In South Korea, a majority also feel connected to the Confucian way of life.

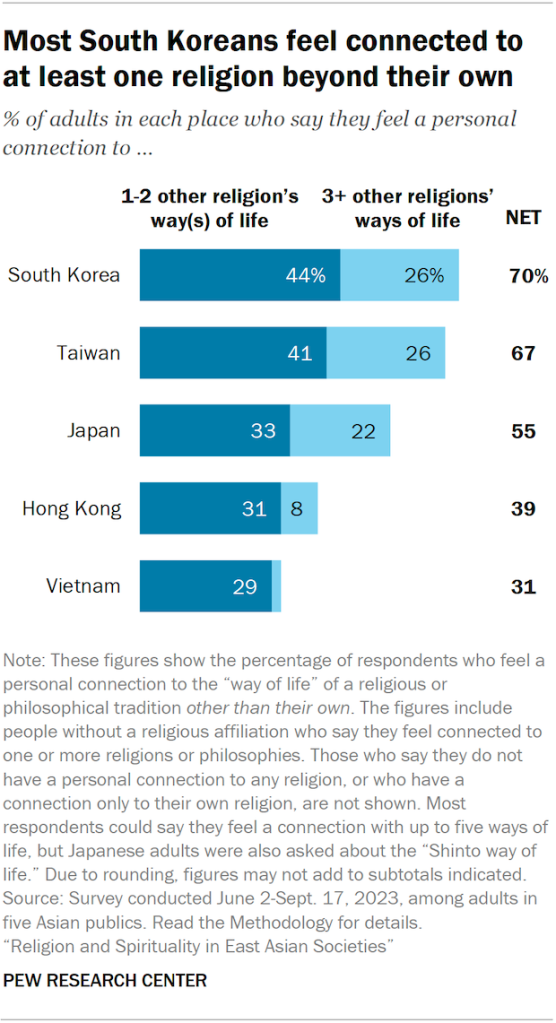

Moreover, adults in the region often express an affinity for multiple traditions. In Japan, for example, 55% of adults say they feel a personal connection to at least one religious or philosophical tradition besides their own.

To measure this, we posed a series of questions, asking separately about Buddhist, Christian, Confucian, Daoist (also spelled Taoist) and local/Indigenous religions’ ways of life. (In Japan, we also asked about the Shinto way of life.)

Except in the case of the local/Indigenous religions item, we avoided using words such as “religion” or “religious tradition,” in part because many people do not consider Confucianism to be a religion. Moreover, we chose phrases like “personal connection” and “way of life” to capture people who might not relate to the word “religion” or formally identify with an organized belief system but who, nonetheless, feel an affinity for the way of life that these traditions or philosophies represent.

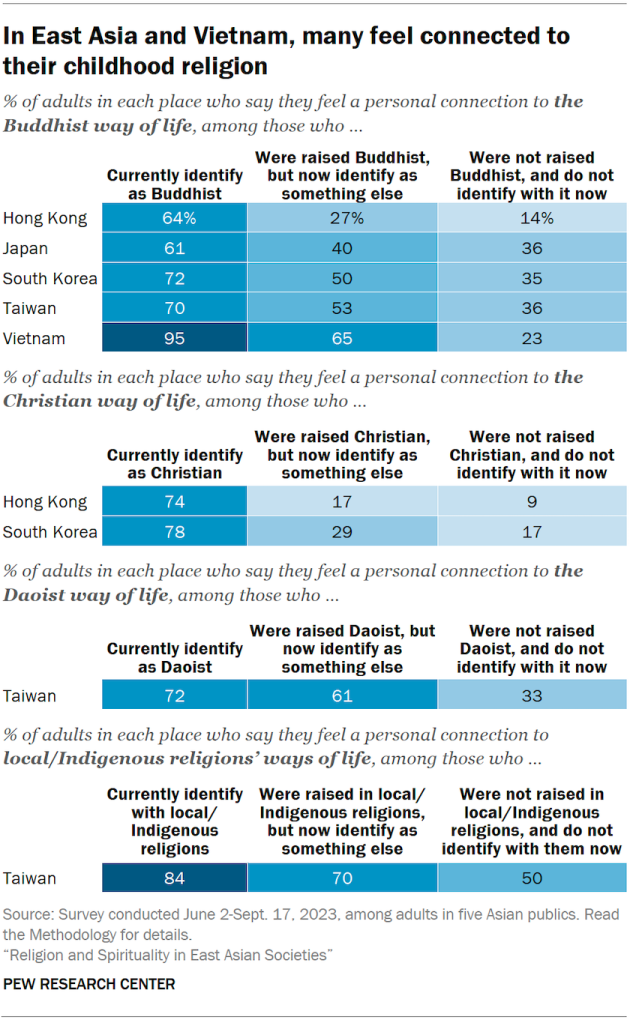

This series of questions also helps to gauge the effect of religious switching, by showing the shares of people who have left their childhood religion but continue to feel a connection to it in adulthood.

In this chapter, we also discuss what adults in East Asia and Vietnam consider Buddhism to be – a culture, a set of ethical teachings, an ethnicity, a religion or a family tradition – as well as the behaviors and attitudes that Buddhists say would disqualify someone from being truly Buddhist.

Feeling connected to one or more religions or philosophies

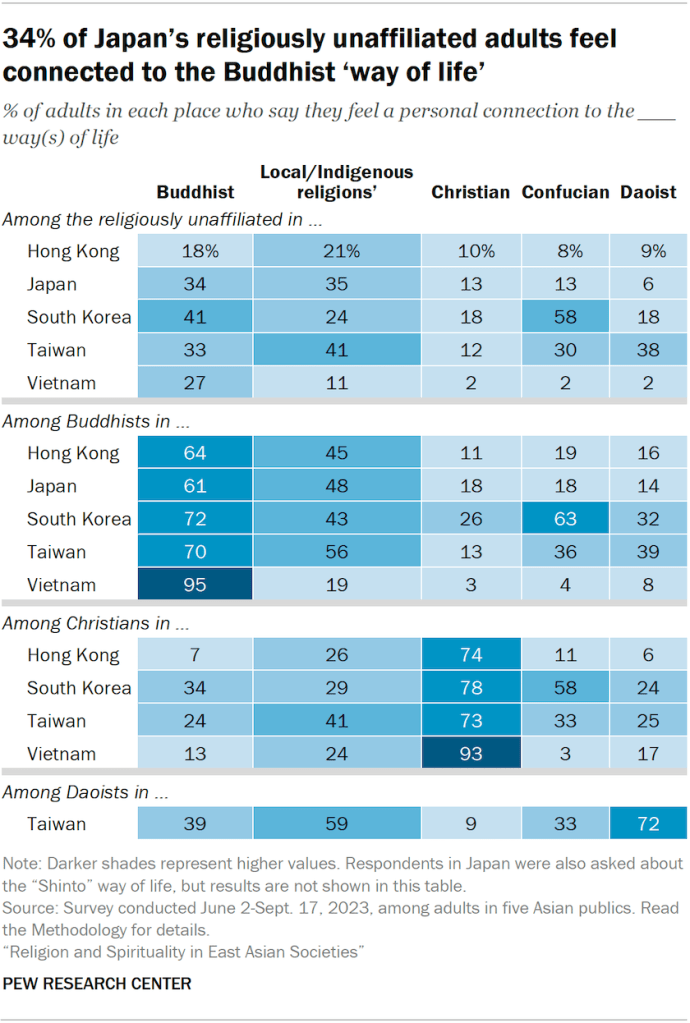

Among the region’s large shares of religiously unaffiliated adults, a fair number express a personal connection to at least one religious or philosophical “way of life.”

At least a third of religiously unaffiliated adults in South Korea, Japan and Taiwan say they feel a personal connection to the Buddhist way of life, and roughly one-quarter or more feel connected to a local or Indigenous religion’s way of life.

In South Korea, 58% of the religiously unaffiliated express a personal connection to the Confucian way of life.

People who formally identify with a religion are even more likely to say they feel a personal connection to that tradition’s way of life.

Among Buddhists across the region, at least six-in-ten say they feel a personal connection to the Buddhist way of life, including 95% of Vietnamese Buddhists who say this. (The percentage of people inside a group who say they feel a personal connection to the group’s way of life may be an indicator of the intensity of their sense of belonging.)

Among Christians, about three-quarters or more feel a personal connection to the Christian way of life. (The attitudes of Christians in Japan are not broken out separately because the sample size is too small.)

Christians are less likely than Buddhists to feel a connection to local or Indigenous religions. In all places surveyed except Vietnam, at least four-in-ten Buddhists say they feel connected to an Indigenous or local religion’s way of life.

Affinity for traditions besides one’s own

Taiwanese and South Korean adults are somewhat more likely than people in other places to feel a personal connection to some other religion’s way of life. In Taiwan, 39% of Buddhists, 38% of the religiously unaffiliated and 25% of Christians say they feel connected to the Daoist way of life. In South Korea, majorities of Buddhists, Christians and the unaffiliated express a personal affinity for the Confucian way of life.

More broadly, over half of all adults in South Korea (70%), Taiwan (67%) and Japan (55%) say they feel connected to at least one tradition besides their own, compared with smaller shares in Hong Kong (39%) and Vietnam (31%) who express similar connections.

Respondents in Japan were also asked whether they feel a personal connection to the Shinto way of life. Shinto is a set of traditional Japanese beliefs that can include the worship of gods and spirits known as kami. Though only 4% of adults in Japan identify Shinto as their religion, fully 27% say they feel a personal connection to the Shinto way of life. (In answers to a separate question, 38% of Japanese adults say they pray or offer respects to kami. Read more on this in Chapter 4.)

Connections to one’s former religion

Given the high rate of religious switching in East Asia and Vietnam, we explored what happens to religious connections after people leave a formal identity behind. Specifically, we compared responses about personal connections among:

- Those who currently identify with a tradition;

- Those who were raised in that tradition but have since left; and

- Those who were not raised in that tradition nor identify with it now.

We consistently find a spectrum of attachments: People who no longer identify with a religion are less likely than those who do so currently to say they feel a personal connection to it. Still, people who were raised in a religion and have since left it are more likely to express a connection to that religion than are people who were not raised in it and who don’t identify it as their religion today.

For example, 72% of South Koreans who currently identify as Buddhist say they feel a personal connection to the Buddhist way of life. Among South Koreans who were raised Buddhist but no longer identify that way, 50% feel such a connection. And among all other South Korean adults, only 35% say they have a personal connection to Buddhism.

How many religions can be true?

We know from past research that the five places included in this survey are very religiously diverse compared with other countries and territories around the world.

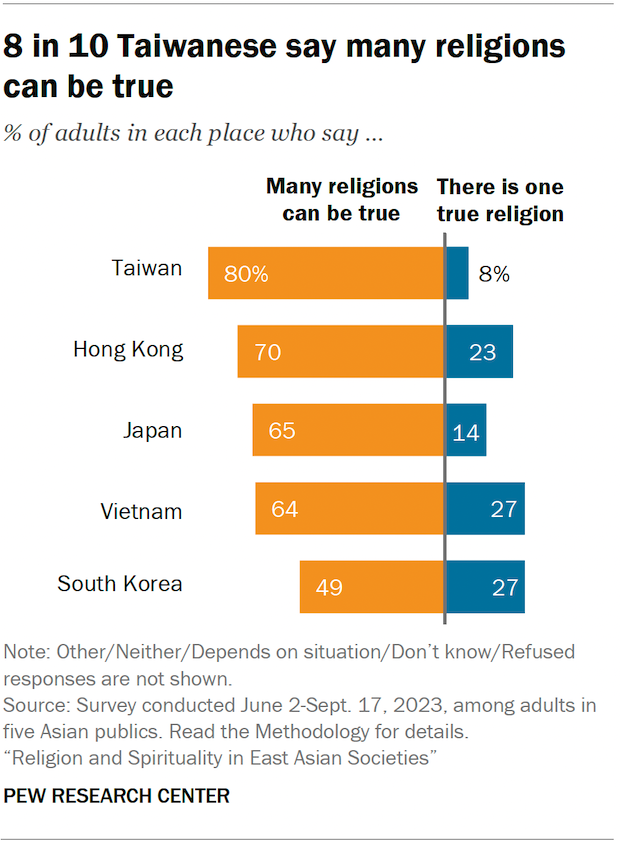

Given this diversity – and the extent to which people feel connected to traditions outside their own – it is perhaps unsurprising that respondents in this survey are more likely to say that “many religions can be true” than to say that “there is only one true religion.”

Among both Buddhists and the religiously unaffiliated, majorities in nearly all five places say that many religions can be true. But Christians are less likely to take this position.

In Taiwan, for example, roughly eight-in-ten Buddhists and unaffiliated adults – but only half of Christians – say that many religions can be true.

In general, younger adults and people with more education are more likely to say that many religions can be true. For example, the vast majority of Japanese adults under the age of 35 say that many religions can be true, compared with a slim majority of older Japanese adults (86% vs. 59%).

Personal importance of religion

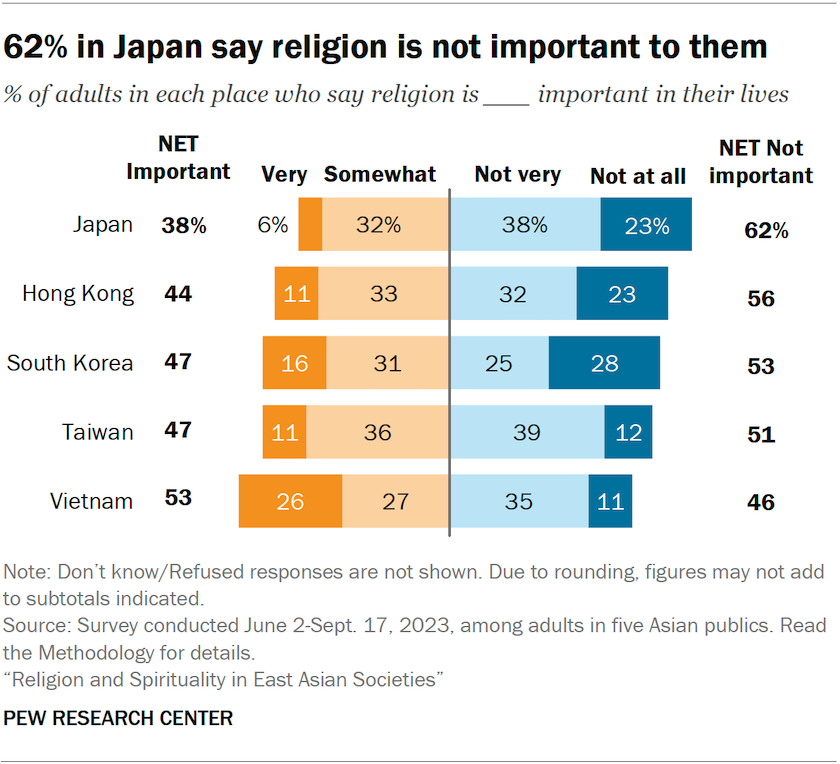

When asked how important religion is in their lives, people in the region tend to say religion is either not very or not at all important to them.

In Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong and Japan, half or more say religion is not very or not at all important.

Only in Vietnam are adults more likely to say religion is important in their lives than to say it is not important (53% vs. 46%).

In no place surveyed do more than about a quarter of adults say religion is very important in their lives.

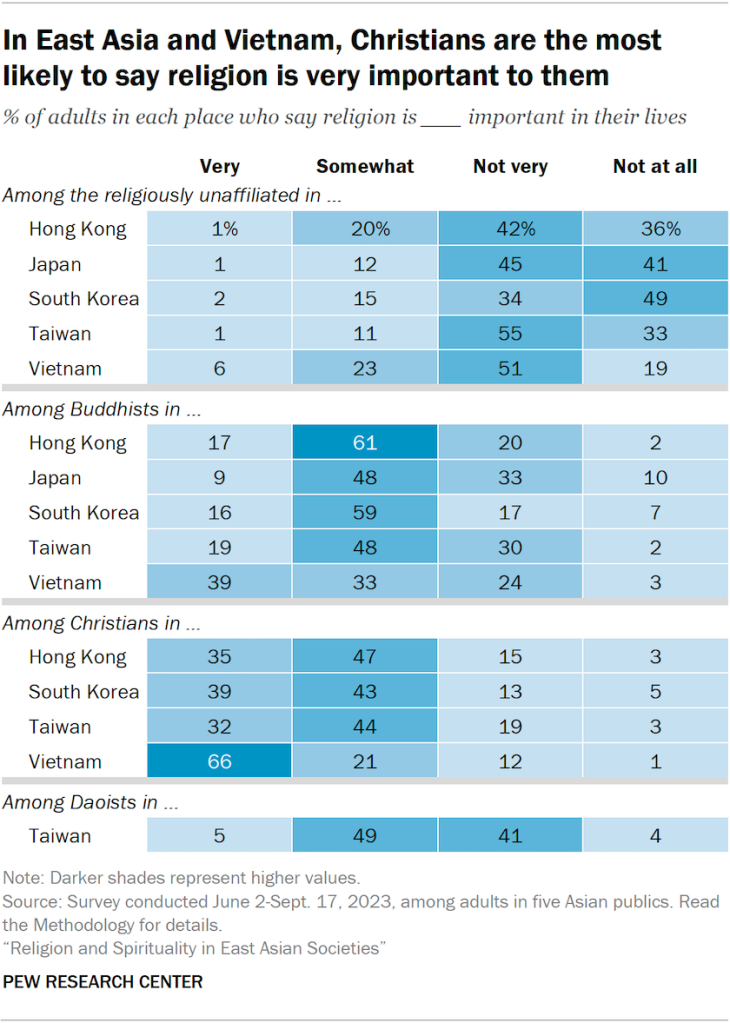

Christians are the most likely to consider religion to be very important to them. About a third of Christians or more across the region say this, including two-thirds of Vietnamese Christians.

Far fewer Buddhists say religion is very important to them. However, many Buddhists surveyed say that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives.

The religiously unaffiliated are the group least likely in this analysis to say religion is very important in their lives. Still, between 11% and 30% of the unaffiliated in each place surveyed say religion is at least somewhat important to them.

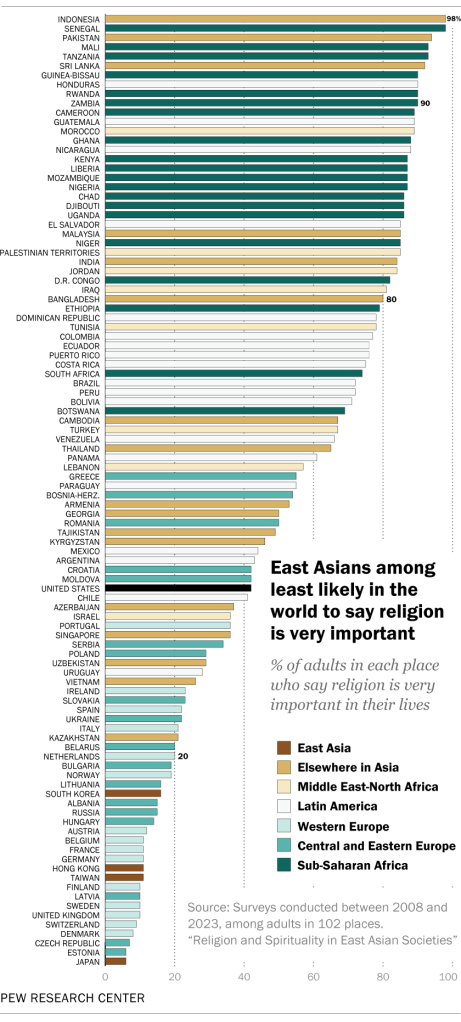

Importance of religion around the world

In all four East Asian societies surveyed, fewer than two-in-ten adults say religion is very important in their lives.

Only in Europe do similarly small percentages say this, according to surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center in 102 countries and territories since 2008.7 For instance, 11% of adults in Hong Kong and Taiwan say religion is very important in their lives – as do 11% of adults in Belgium, France and Germany.

Other parts of the world have much higher shares who say religion is very important. This includes majorities across Africa and much of Latin America.

In the United States, 42% of adults say religion is very important in their lives.

(For information on when we conducted surveys in various countries and territories, go to Appendix A.)

What people say Buddhism is – and is not

Given that large shares of East Asians and Vietnamese adults identify with Buddhism or feel connected to its way of life, we wanted to explore what people in the region understand Buddhism to be.

Do they view Buddhism as a set of ethical teachings to guide actions? A culture one is a part of? A religion one chooses to follow? A family tradition one must follow? An ethnicity one is born into?

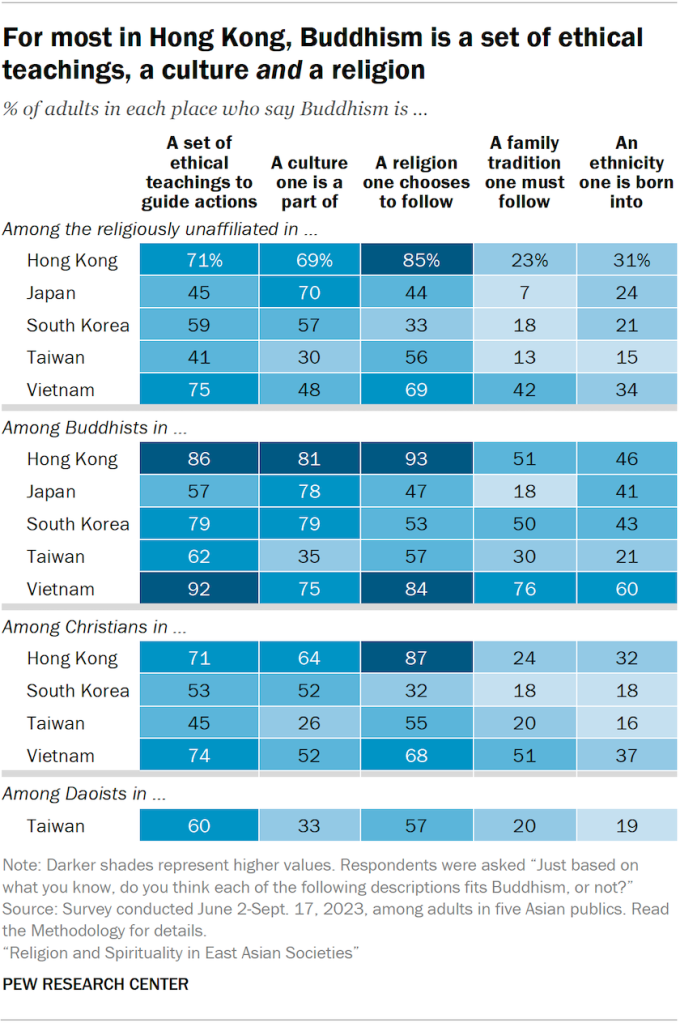

Across the region, large shares of adults in all religious groups – including overwhelming majorities of Buddhists in Hong Kong and Vietnam – say that Buddhism is a set of ethical teachings, a culture and a religion.

Buddhists are more likely than people in other religious groups to say Buddhism fits each description on the list. For example, roughly four-in-ten Buddhists in South Korea say Buddhism is an ethnicity, compared with about a fifth of South Korean Christians who say this (43% vs. 18%).

In Vietnam, 48% of Buddhists say their religion can be described by all five statements – i.e., that Buddhism is a religion, a set of ethics, a culture, a family tradition and an ethnicity. Far fewer Buddhists in Taiwan (6%) and Japan (4%) say all five statements describe Buddhism; Taiwanese Buddhists are least likely to describe Buddhism as an ethnicity, and Japanese Buddhists are least likely to call it a family tradition.

What can a person do and still be ‘truly’ Buddhist?

In addition to asking all respondents what Buddhism is, the survey asked those who identify as Buddhist whether certain beliefs or practices would disqualify a person from being “truly” Buddhist.

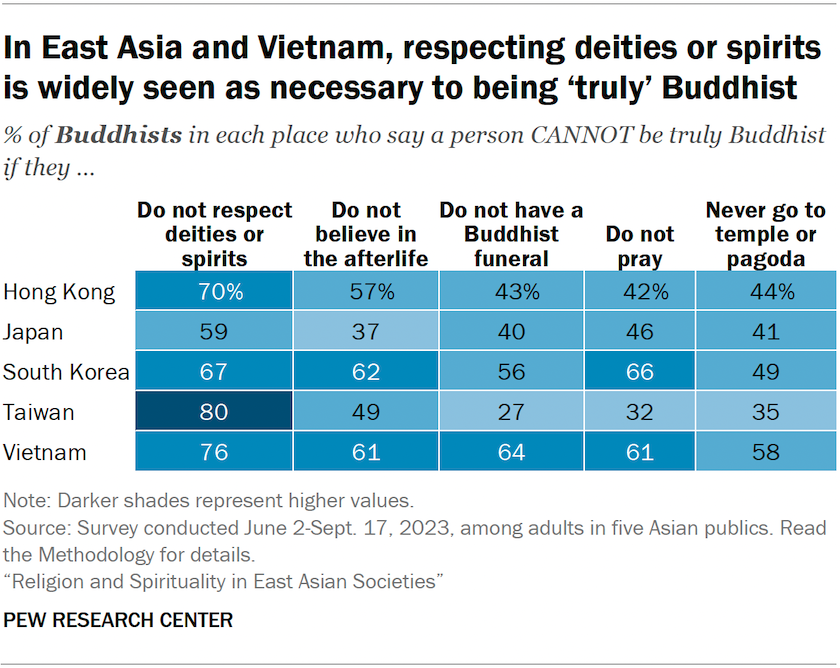

There is general agreement among Buddhists that not respecting deities or spirits would disqualify one from being truly Buddhist. Majorities of Buddhists in every place surveyed, ranging from 59% in Japan to 80% in Taiwan, say this.

Buddhists in Vietnam and South Korea are more likely than those elsewhere to say that several other beliefs or practices are crucial to being Buddhist. For example, 64% of Buddhists in Vietnam and 56% of Buddhists in South Korea say a person cannot be truly Buddhist if they do not have a Buddhist funeral. Fewer Buddhists in Hong Kong (43%), Japan (40%) and Taiwan (27%) say the same.

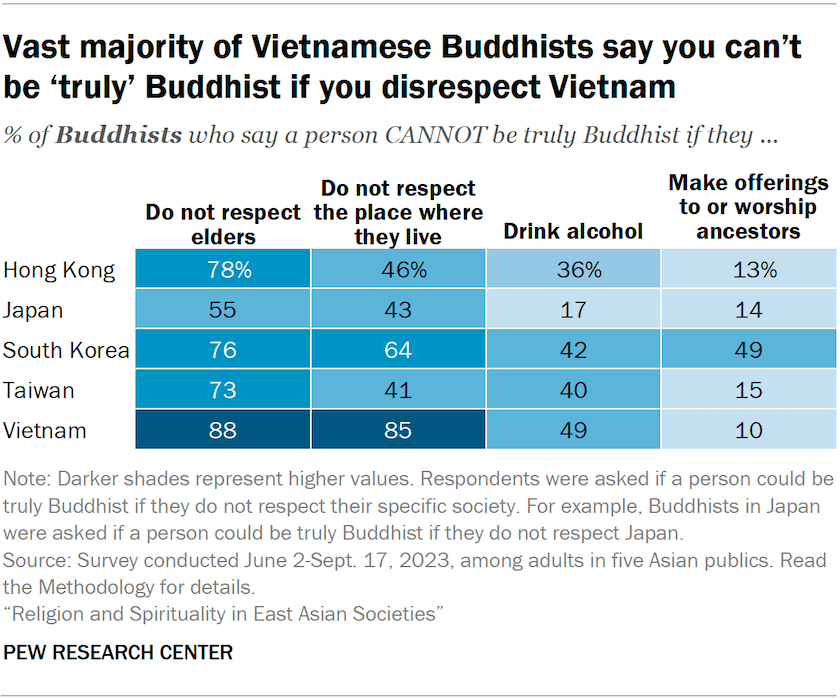

Most Buddhists surveyed across the region say you cannot be truly Buddhist if you do not respect elders, including nearly nine-in-ten Vietnamese Buddhists who say this.

Fewer Buddhists say that you cannot be Buddhist if you drink alcohol. (Avoiding intoxicants such as alcohol is one of the Five Precepts, a set of Buddhist teachings on morality for laypeople.)

Buddhists in the region are more divided as to whether one must respect where one lives to be truly Buddhist. Majorities in Vietnam (85%) and South Korea (64%) say a person cannot be Buddhist if they do not respect Vietnam or South Korea, respectively. In Taiwan, far fewer Buddhists – 41% – say respecting Taiwan is necessary to be truly Buddhist.

By contrast, clear majorities of Buddhists in all of the South and Southeast Asian places we surveyed in 2022 said that respecting where one lives is key to being truly Buddhist.

Other than in South Korea, very few Buddhists in East Asia and Vietnam say that a person cannot be Buddhist if they make offerings to or worship ancestors. Even smaller shares of Cambodian and Thai Buddhists said this in our 2022 survey. (As discussed in Chapter 5, ancestor veneration practices such as burning incense, offering flowers and lighting candles are very common among Buddhists in East Asia and Vietnam.)

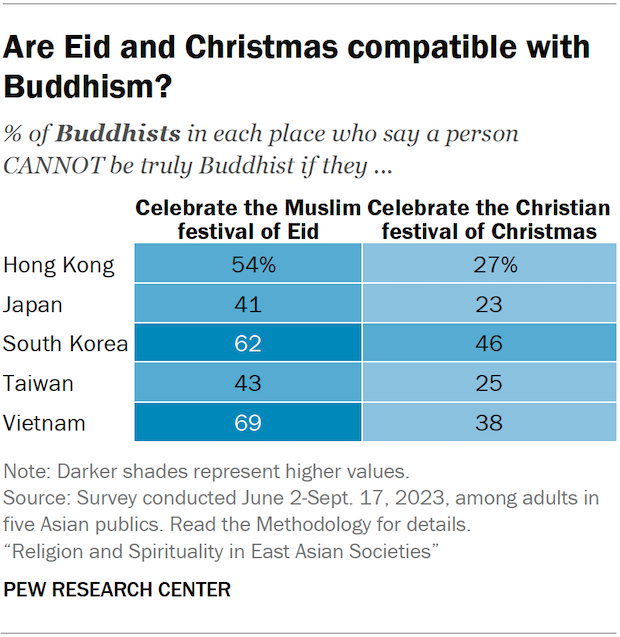

Buddhists in the region are somewhat split about whether celebrating the Muslim festival of Eid is compatible with Buddhism. While six-in-ten Buddhists or more in Vietnam and South Korea say celebrating Eid would disqualify someone from being truly Buddhist, only about four-in-ten Taiwanese and Japanese Buddhists take that position.

Nowhere does a majority think Christmas celebrations stop someone from being truly Buddhist. However, Buddhists in South Korea – which has the largest share of Christians in its population among the places analyzed – are more likely than Buddhists elsewhere to say that celebrating Christmas would disqualify a person from being truly Buddhist.