Typically, East Asia is considered to encompass China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan. In geopolitical terms, Vietnam is often categorized as part of Southeast Asia. But we surveyed Vietnam along with East Asia for several reasons, including its historic ties to China and Confucian traditions. Moreover, Buddhists in Vietnam practice the same strain of Buddhism (Mahayana) found across East Asia.

Throughout this report, the term “East Asia” refers to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

When discussing trends throughout the broader “region,” we include Vietnam.

For legal and logistical reasons, we did not survey several other places that are generally considered part of East Asia. At present, China does not allow non-Chinese organizations to conduct surveys on the mainland, and public opinion surveys are not possible in North Korea. Conducting nationally representative surveys in Mongolia is difficult due to the nomadic lifestyle of a large part of its people. We did not survey Macau because its population is relatively small.

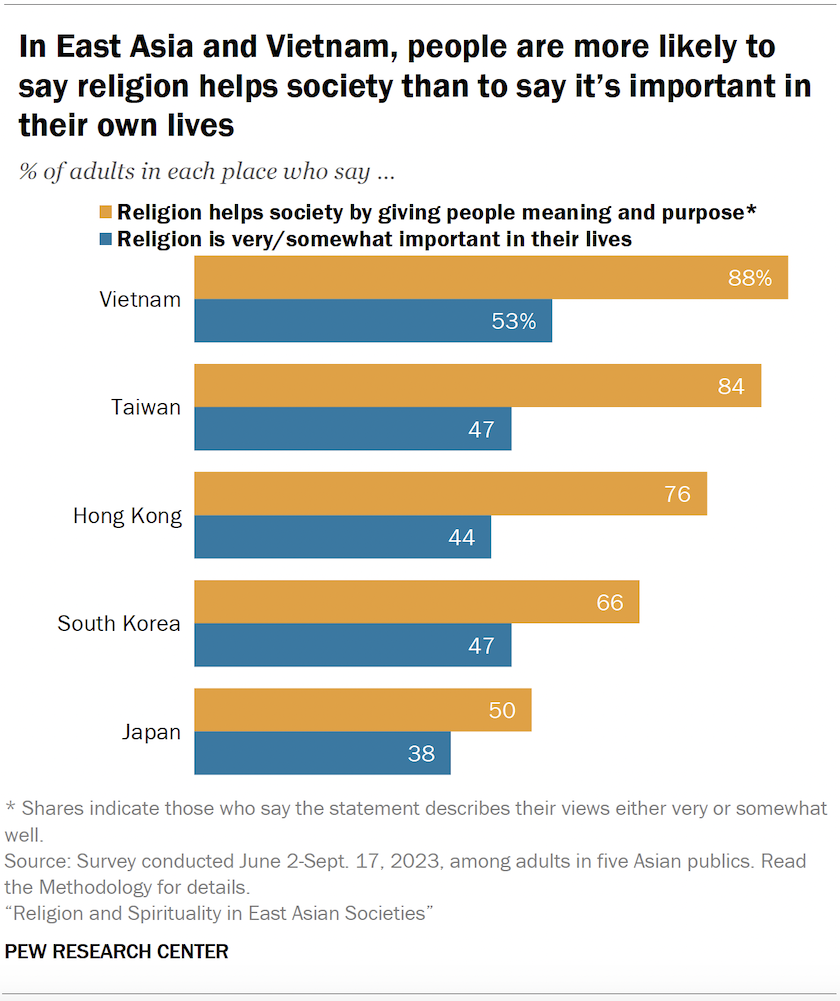

Even though many people in East Asia and neighboring Vietnam do not see religion as important in their own lives, they generally hold positive views about the role of religion in society.

Solid majorities in Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam say religion helps society by giving people purpose and, separately, that it helps guide people to do the right thing. In Japan, about half of adults take these positions.

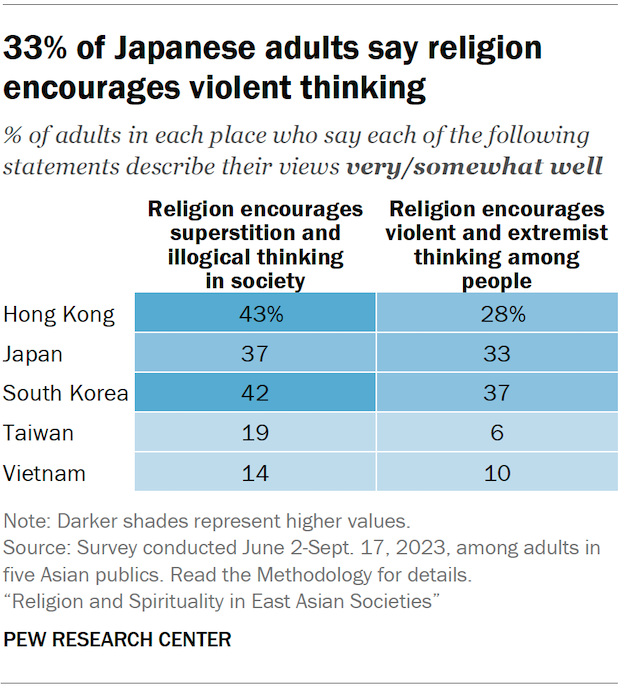

Negative views about religion’s role in society are not as prevalent. Still, roughly four-in-ten people in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea say religion encourages superstition and illogical thinking.

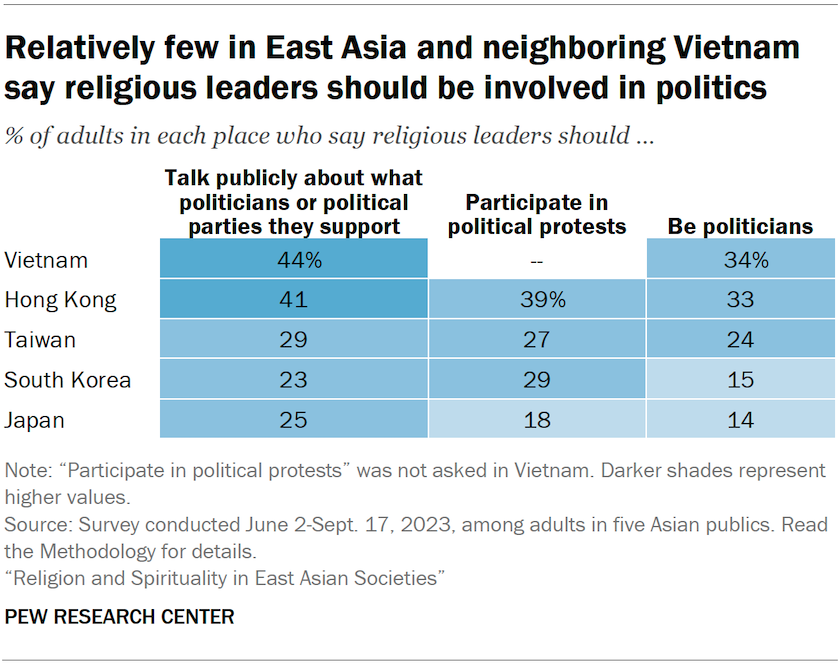

Relatively few people in the places we surveyed say religious leaders should be politicians, participate in political protests, or publicly express their political views. Buddhists, Christians and the religiously unaffiliated broadly agree on these topics.

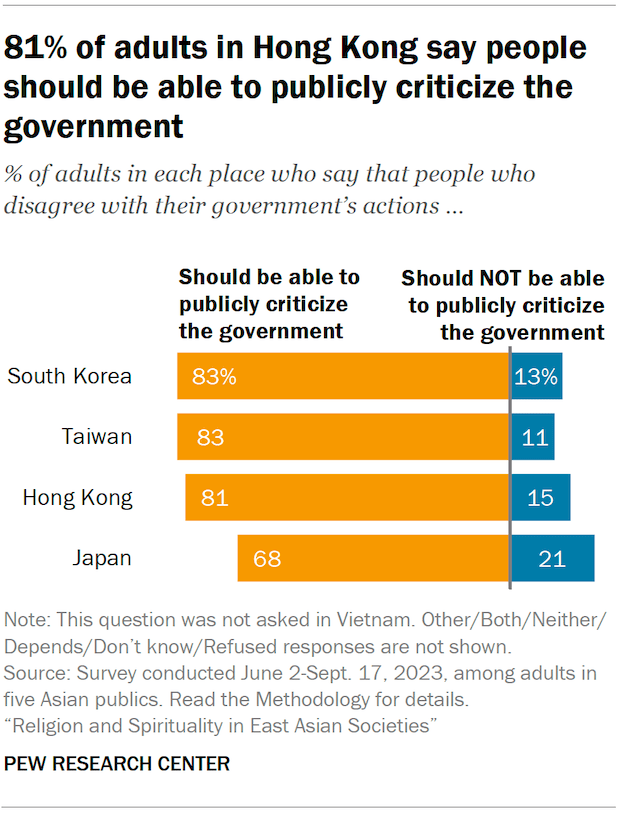

We also asked about free speech, public criticism of authorities, and social change. In general, people in these societies are divided on whether it is more important to allow free speech or to ensure social harmony. But most support the right to publicly criticize their governments. For instance, roughly eight-in-ten adults in Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan say people who disagree with their government’s actions should be able to speak out publicly.

(In Vietnam we did not ask whether people should be able to criticize the government or whether religious leaders should participate in political protests.)

Across the region, many also think their society would be better off in the future if it is open to change, as opposed to sticking to its traditions and way of life. In Hong Kong, Vietnam and Taiwan, about half of adults say their society would benefit from being open to changes. People in South Korea and Japan are even more likely to express this sentiment.

Religion’s role in society

In our survey, we asked people to respond to a series of both positive and negative statements about religion’s value to individuals and to society.

Positive statements:

- “Religion helps society by giving people meaning and purpose in their lives.”

- “Religion gives people guidance so that they do the right thing and treat other people well.”

Many people across the region say these statements align “very well” or “somewhat well” with their own views.

In Vietnam (88%), Taiwan (84%) and Hong Kong (76%), the vast majority agree that religion helps society by giving people meaning and purpose. And similar shares say religion guides people to do the right thing and treat others well. In South Korea, about two-thirds of adults say these statements match their own views.

Japanese adults are the least likely to view religion’s impact positively. Only about half of people surveyed in Japan say either statement describes their own position well.

Generally, Christians across the region are somewhat more likely than other groups to affirm these positive statements. In Hong Kong, for instance, 89% of Christians say religion guides people to do the right thing and treat others well, compared with 78% of Buddhists and 76% of the unaffiliated.

On balance, adults with more education are slightly more likely than those with less education to view religion’s role positively. In Hong Kong, 83% of adults with at least a college education say religion helps society by giving meaning and purpose to people’s lives, while 73% of those with less education take that position.

Negative statements:

- “Religion encourages superstition and illogical thinking in society.”

- “Religion encourages violent and extremist thinking among people.”

Across the region, fewer than half of adults say these negative statements describe their views well. Still, roughly four-in-ten people in Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea say religion encourages superstition and illogical thinking.

Taiwanese and Vietnamese adults are the least likely to view religion negatively: Just 19% in Taiwan and 14% in Vietnam say religion encourages superstition and illogical thinking. Even fewer in both places say that religion encourages violent and extremist thinking.

Religious leaders in politics

What about the role of religious leaders in political life? The survey asked whether religious leaders should be politicians, talk publicly about which politicians or political parties they support, or participate in political protests.

Overall, relatively few people across the region say they want religious leaders to be involved in such political activities. And support is lowest for religious leaders being politicians.

People in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan are the least supportive of political involvement by religious leaders, while adults in Hong Kong and Vietnam are somewhat more supportive. For example, 24% of Taiwanese, 15% of South Korean and 14% of Japanese adults say religious leaders should be politicians, compared with about a third in both Hong Kong and Vietnam who say this.

(We also previously asked these questions in South and Southeast Asia.)

Across East Asia and neighboring Vietnam, differences between religious groups on questions of political involvement are relatively modest.

But in South Korea, there are some partisan differences. Adults who feel closest to the liberal Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) are more likely than those who back the conservative People Power Party (PPP) to say religious leaders should talk publicly about what politicians or political parties they support (28% vs. 19%). DPK supporters are also more likely than PPP supporters to say religious leaders should participate in political protests (38% vs. 20%).

Free speech and social harmony

Our survey asked two questions about political speech and dissent:

- Whether people who disagree with the government should be able to express their criticisms publicly; and

- Whether people should be allowed to speak their opinions, even if they upset other people, or whether harmony with others is more important than the right to speak one’s opinion.

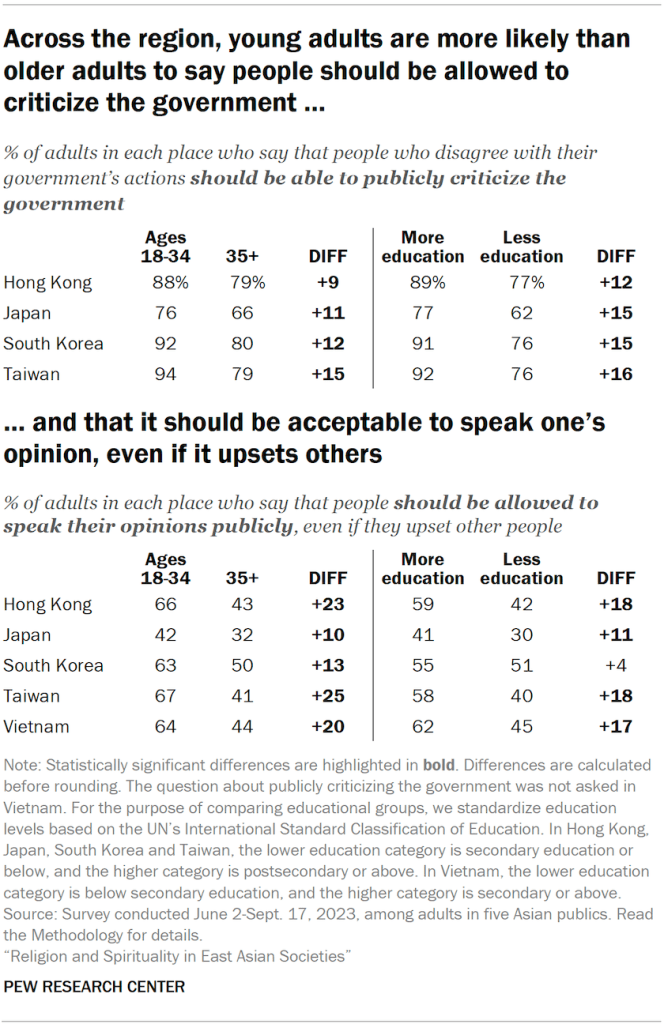

On the first question, most adults across the region say people who disagree with their government’s actions should be able to publicly criticize it. Adults in South Korea (83%), Taiwan (83%) and Hong Kong (81%) take this position most strongly, while 68% of Japanese share the same view. (As previously noted, this question was not asked in Vietnam.)

In South Korea, religiously unaffiliated adults (88%) are more likely than Christians (80%) and Buddhists (75%) to say people should be able to publicly criticize the government if they disagree with its actions. A similar pattern prevails in Taiwan, where 87% of unaffiliated people, 79% of Buddhists and 78% of Christians support this position.

In Japan, supporters of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) are considerably less likely than adults who feel closest to the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin) to say people should have the right to publicly criticize the government (58% vs. 79%).

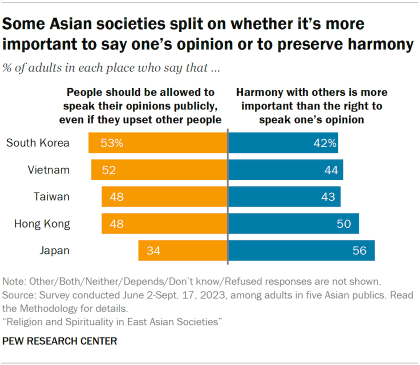

People across the region are more narrowly divided on the question of whether free speech should be a higher priority than social harmony.

In South Korea and Vietnam, respondents are slightly more likely to say that people should be allowed to express their opinions publicly than to say that harmony with others is paramount (53% vs. 42% in South Korea; 52% vs. 44% in Vietnam).

Residents of Hong Kong (48% vs. 50%) and Taiwan (48% vs. 43%) are roughly evenly split on this question.

Japan stands out as the only place surveyed where a majority take the position that harmony with others is more important than the right to speak one’s opinion.

In Taiwan, partisanship also plays a role. Taiwanese who feel closest to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are significantly more likely than those who align with the more conservative Kuomintang (KMT) to say that people should be allowed to speak their opinions publicly, even if it upsets others (57% vs. 41%).

In all five places, younger adults (ages 18 to 34) are more likely than older adults to say people should be able to speak their opinions publicly, even if they upset other people. In Vietnam, for instance, this gap is 20 percentage points (64% vs. 44%).

In the four places we asked the question, younger adults also are more likely to say that people should be able to criticize their government, though majorities of older adults feel this way, too.

In Japan, there is a large gender gap among younger adults on the question about speaking one’s opinion in public. Younger men are significantly more likely than younger women to prioritize the right to speak one’s opinion, even if it disrupts social harmony (51% vs. 33%).

Adults with more education are more likely than those with less education to support speaking freely. For example, 59% of Hong Kongers with a college education say people should be able to speak freely even if it upsets other people, while 42% of those with less than a college education take the same position.

Should societies be open to change?

We also asked respondents whether their society would be better off in the future if it “sticks to its traditions” or “is open to changes.”

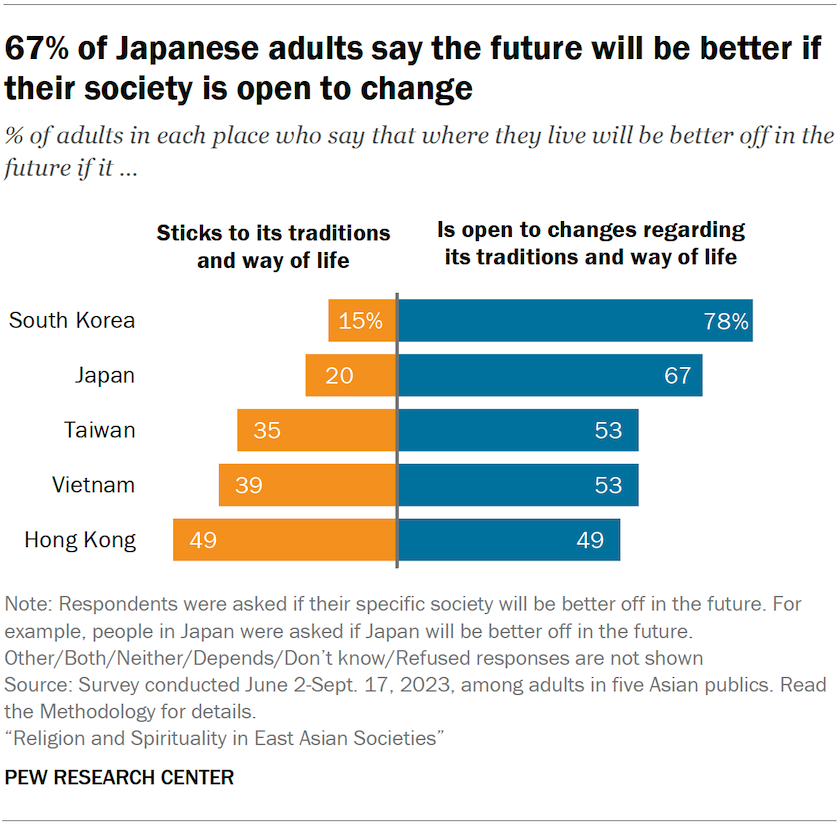

Most South Korean (78%) and Japanese (67%) adults say their societies will be better off if they are open to changes.

In Taiwan and Vietnam, about half of adults say their societies will be better off if they are open to change, but that is still the most widely held view. (Other respondents say they don’t know, decline to answer, or volunteer other responses.)

In Hong Kong, the public is evenly split: 49% say Hong Kong will be better off sticking to its traditions, and the same share say it should be open to change.

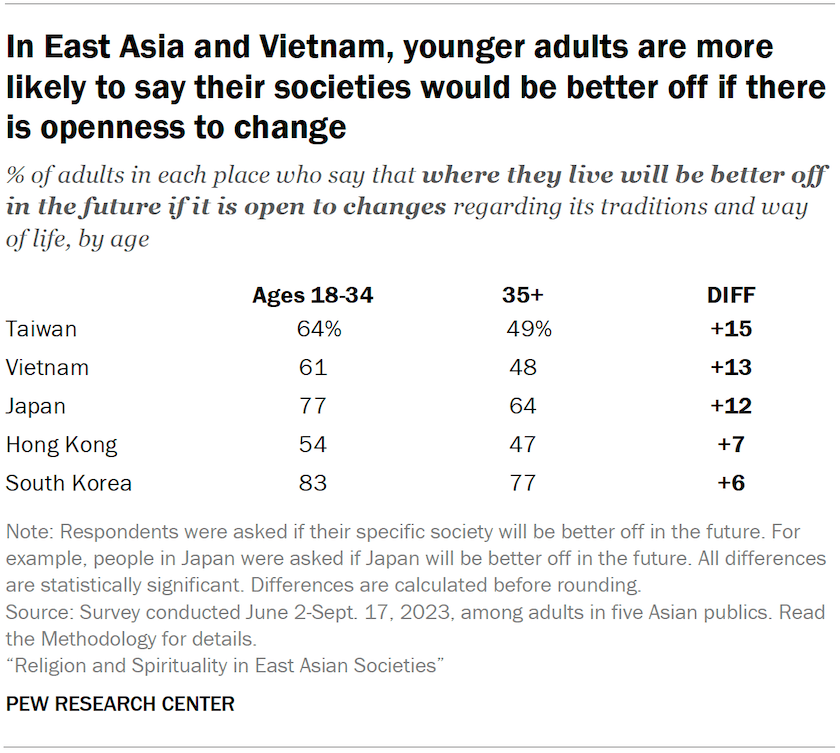

In all the places we surveyed, adults younger than 35 are more likely than their elders to express openness to changing traditions. In Japan, for example, 77% of younger adults express this attitude, compared with 64% of older adults. Still, in every society, roughly half of older adults or more take this position, topping out at 77% of South Koreans ages 35 and older.

Adults with more education generally are more likely than those with less education to say the future will be better if their society is open to change.