The United Nations counts international migrants as people of any age who live outside their country (or in some cases, territory) of birth – regardless of their motives for migrating, their length of residence or their legal status.

In addition to naturalized citizens and permanent residents, the UN’s international migrant numbers include asylum-seekers and refugees, as well as people without official residence documents. The UN also includes some people who live in a country temporarily – like some students and guest workers – but it does not include short-term visitors like tourists, nor does it typically include military forces deployed abroad.

For brevity, this report refers to international migrants simply as migrants. Occasionally, we use the term immigrants to differentiate migrants living in a destination country from emigrants who have left an origin country. Every person who is living outside of his or her country of birth is all three – a migrant, an immigrant and an emigrant.

The analysis in this report focuses on existing stocks of international migrants – all people who now live outside their birth country, no matter when they left. We do not estimate migration flows – how many people move across borders in any single year.

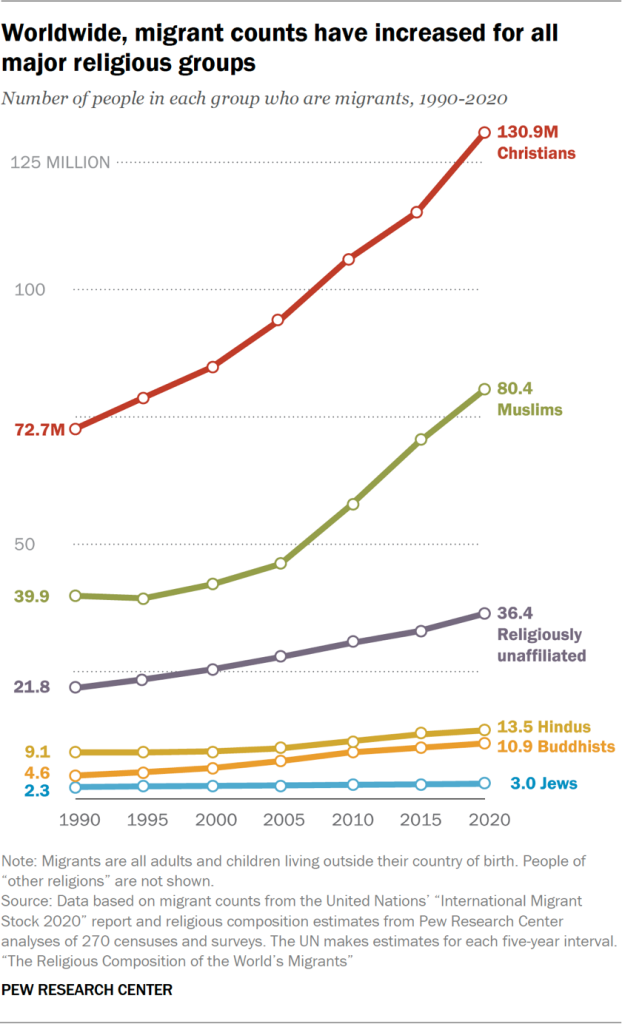

The number of people living outside their country of birth rose by 83% between 1990 and 2020, from 153 million to 281 million. Migration during this timespan outpaced growth in the global population, which rose by 47% to 7.8 billion people.

The number of Buddhist and Muslim migrants more than doubled during this period. Other groups of migrants grew more modestly – Christians by 80%, the religiously unaffiliated by 67%, Hindus by 48% and Jews by 28%.

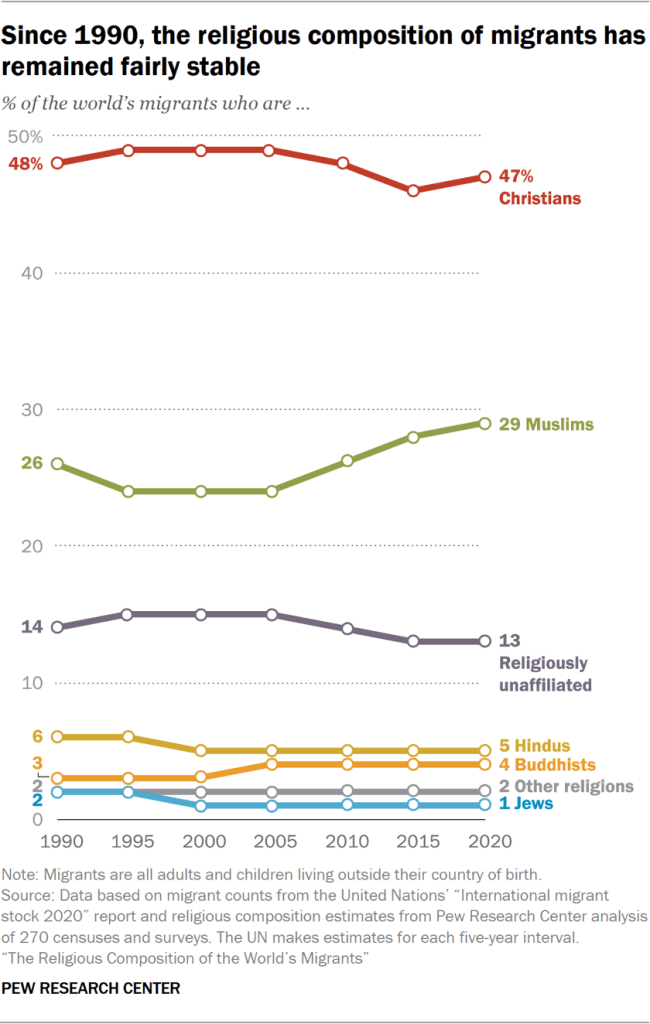

However, the religious composition of the global migrant population has not changed dramatically from a few decades ago. This is largely because the sizes of each migrant stock were so unequal in 1990. Even though the migrant populations have grown at different rates in recent decades, their mix in 2020 still reflects the large differences in their initial sizes in 1990.

Several major political and economic events in recent decades had big impacts on the migration patterns of individual religious groups.

For example, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 caused a surge of Jewish migrants to Israel and the United States. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that took effect in 1994 contributed to agricultural unemployment in Mexico that sent millions of Christian migrants to the U.S.7 The Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, pushed millions of Muslims into countries including Turkey, Germany and Lebanon.

Historic events that happened before 1990 also played a role in shaping the patterns described in this report.

For example, during India’s 1947 Partition, millions of Muslims migrated north to the newly created country of Pakistan (which at the time included modern-day Bangladesh). Between 1990 and 2020, many of these migrants reached the ends of their lives, bringing down Pakistan’s foreign-born population.

Growth of migrants among each religious group, 1990-2020

- Christian migrants grew from 72.7 million in 1990 to 130.9 million in 2020 – an 80% increase. Over the decades, the share of migrants worldwide who are Christian has ranged from 47% to 49%.

- Muslim migrants increased from 39.9 million to 80.4 million (up 102%). During this time, Muslims have always made up between 24% and 29% of migrants globally.

- Religiously unaffiliated migrants grew from 21.8 million to 36.4 million (up 67%). Since 1990, an estimated 13% to 15% of international migrants have been unaffiliated.

- Hindu migrants increased from 9.1 million to 13.5 million (up 48%). Hindus have consistently made up between 5% and 6% of the world’s migrant population.

- Buddhist migrants grew from 4.6 million to 10.9 million (up 137%). Buddhists have made up a stable 3% to 4% of the international migrant population over the past few decades.

- Jewish migrants grew from 2.3 million to 3.0 million (up 28%). Jews have consistently represented between 1% and 2% of migrants globally.

Regional patterns over time

Since 1990, the migrant populations in each destination region have grown at different rates.

The rate of growth since 1990 has been greatest in the Middle East-North Africa region (up 185%). The Asia-Pacific region has had the smallest increase (up 38%).

Most major religions have seen their migrant numbers rise in every region. But some groups have seen a decline in their migrant shares (the percentage their religion makes up of all migrants in the region).

As in other parts of this report, migrants are defined here as people who are living outside their country (or in some cases, territory) of birth, regardless of when they moved or how far. Many have stayed in the region in which they were born.

Asia-Pacific

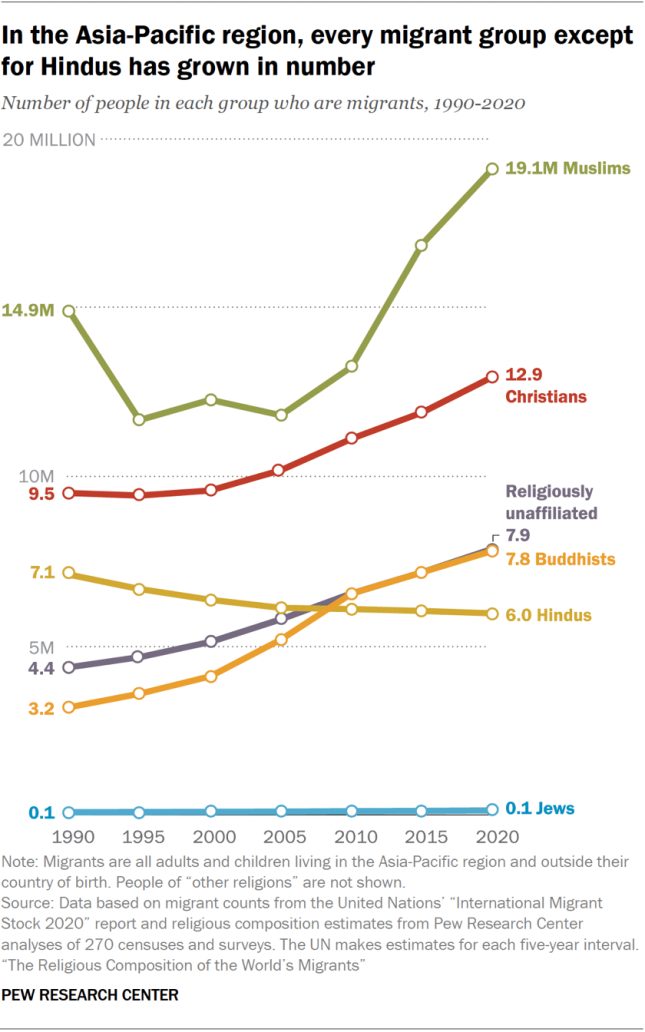

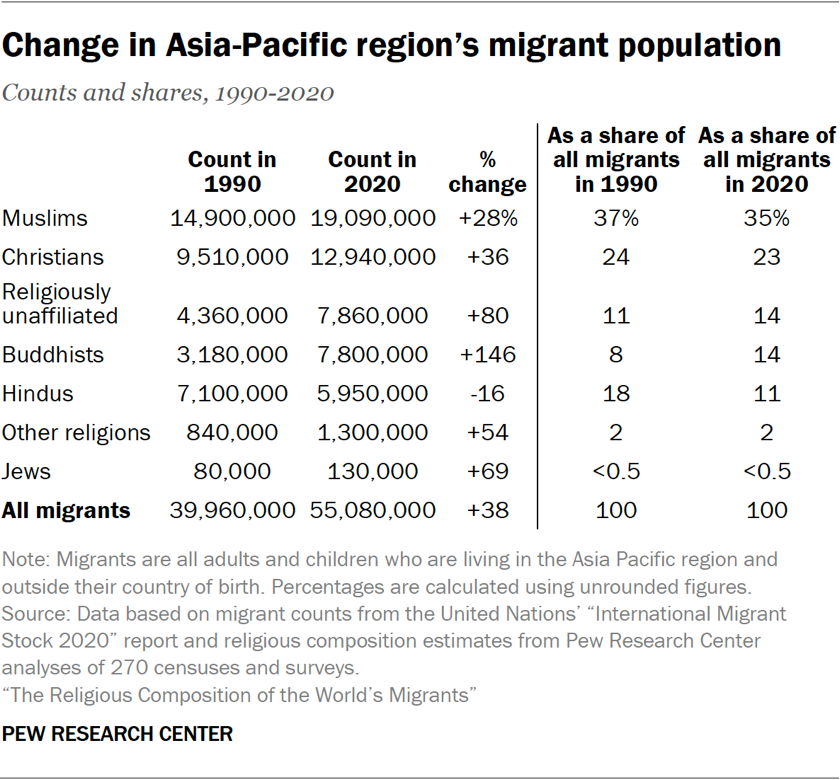

The total number of international migrants living in the Asia-Pacific region grew by 38% between 1990 and 2020, reaching 55 million in 2020.

The region’s overall population – which in 1990 was already the world’s largest – grew 43% in this period, to 4.5 billion.

Migrants made up 1% of the region’s population in both 1990 and in 2020. Growth was concentrated between 2005 and 2020, driven by large increases from Syria, Myanmar (also called Burma) and China.

Hindus were the only major religious group with a migrant population that declined in absolute numbers.

Muslims were the largest migrant group in Asia both in 1990 and in 2020. Between these years, the number of Muslim migrants living in the region grew by 28% to 19.1 million.

However, there was an initial decrease in the Muslim migrant population between 1990 and 1995, as Afghanistan-born Muslims returned home after the Soviet occupation ended in 1989. Many Muslims who moved due to India’s 1947 Partition also died over the years. Since 2010, there has been sharp growth in Muslim migrants in the region, as new conflicts have unfolded in Syria and Myanmar.

Christians, the region’s second-largest group of migrants, have grown by 36% over the decades, to 12.9 million in 2020. About 3 million Christian migrants living in Asia were born in Russia, down from 3.6 million in 1990.

Religiously unaffiliated migrants in the Asia-Pacific region increased by 80% between 1990 and 2020, to nearly 8 million.

Buddhists are the second-largest group of migrants – behind religiously unaffiliated migrants – living in Asia-Pacific countries. Buddhist migrants grew by 146% from 1990 to 2020. This makes Buddhists the fastest-growing migrant group in the region, even though their total count (7.8 million in 2020) is much smaller than Muslim migrants’ numbers. Buddhists born in Myanmar were particularly likely to have migrated during this period, with their population increasing seven times to roughly 2 million in 2020.

While other migrant groups were growing, the Hindu figure dropped by 16%, to 6 million. This decline was due in part to the gradual death of Hindu migrants who had moved around the time of India’s 1947 Partition.

Since 1990, Jews have been the smallest migrant group in the Asia-Pacific region. While the Jewish migrant population grew by 69%, it remained tiny at an estimated 130,000 in 2020.

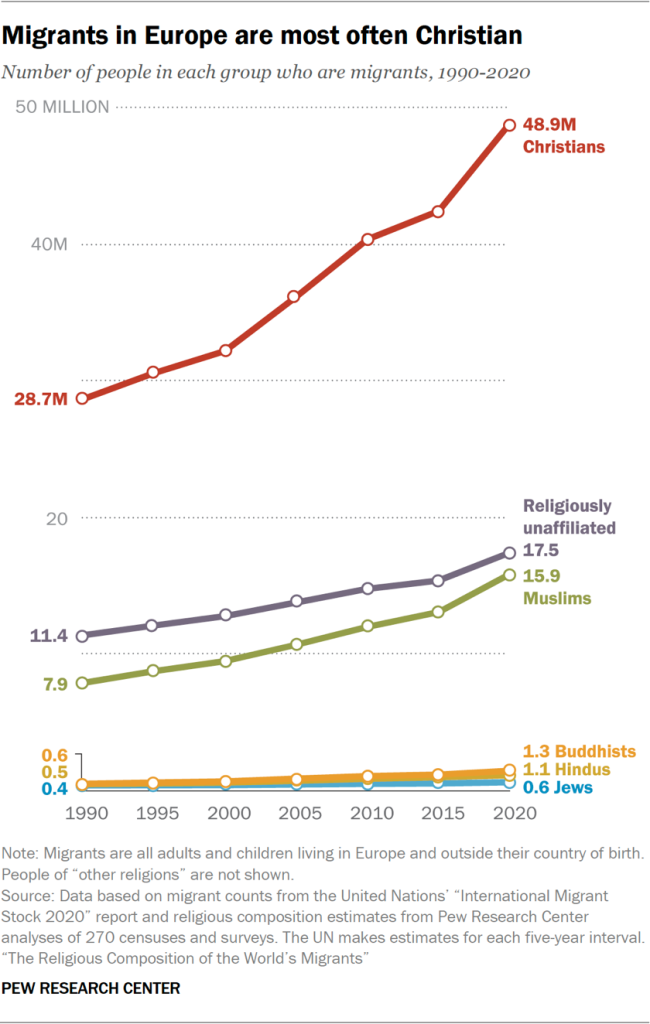

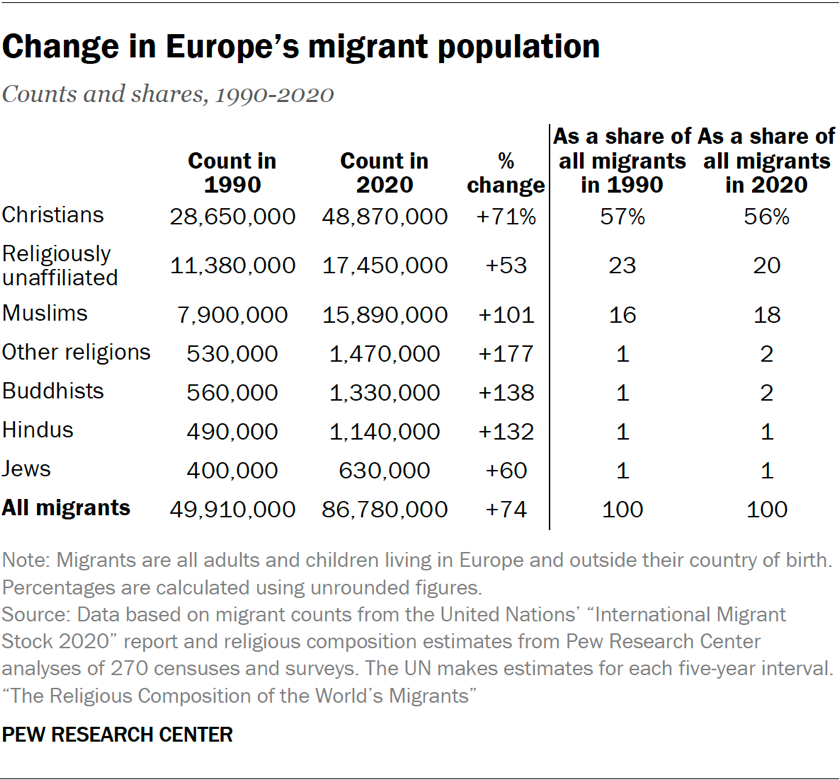

Europe

The total number of international migrants living in Europe has risen by 74% since 1990, approaching 87 million in 2020. The region’s overall population grew by just 3% over this period, to nearly 750 million.

As a result, migrants jumped from 7% of the region’s total population in 1990 to 12% in 2020. And migrants from every major religious group increased in number.

Christians were by far the largest migrant group across the decades. Since 1990, the number of Christian migrants has grown by 71% to nearly 49 million in 2020.

Christian migrants from Russia and Ukraine were most numerous in both 1990 and 2020. But the largest growth in numbers came from Poland and Romania.

Since 1990, the number of religiously unaffiliated migrants increased by 53% – the least of any group – to more than 17 million in 2020. During this time, much of Europe’s native-born population has been secularizing, and the relatively moderate growth of unaffiliated migrants has dampened that shift.

Muslims make up the third-largest migrant group in Europe. Their number doubled to almost 16 million in 2020, as many Muslims came to Europe from Morocco, Syria, Turkey and Pakistan.8

All other religious groups accounted for far fewer people over these years, never totaling much more than 2% of the migrant population each.

Still, the number of Buddhist migrants in Europe more than doubled to 1.3 million, and Hindus grew at a similar rate to 1.1 million. Many Buddhists arrived from China and Thailand during these decades, while Hindus tended to arrive from India.

People in the “other religions” category, including many Sikhs and Jains from India, experienced the largest growth in percentage terms, nearly tripling from an estimated 530,000 in 1990 to almost 1.5 million in 2020.

The Jewish migrant population in Europe increased by 60% from 1990 to 2020, bringing their total to 630,000. Jews were the smallest major religious group among the region’s migrants in both 1990 and 2020.

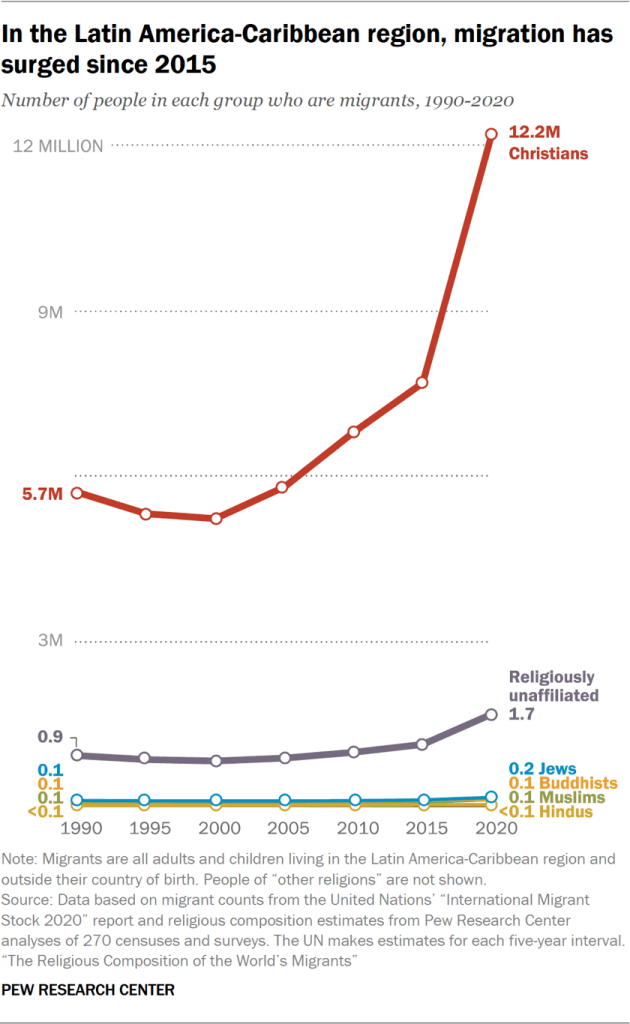

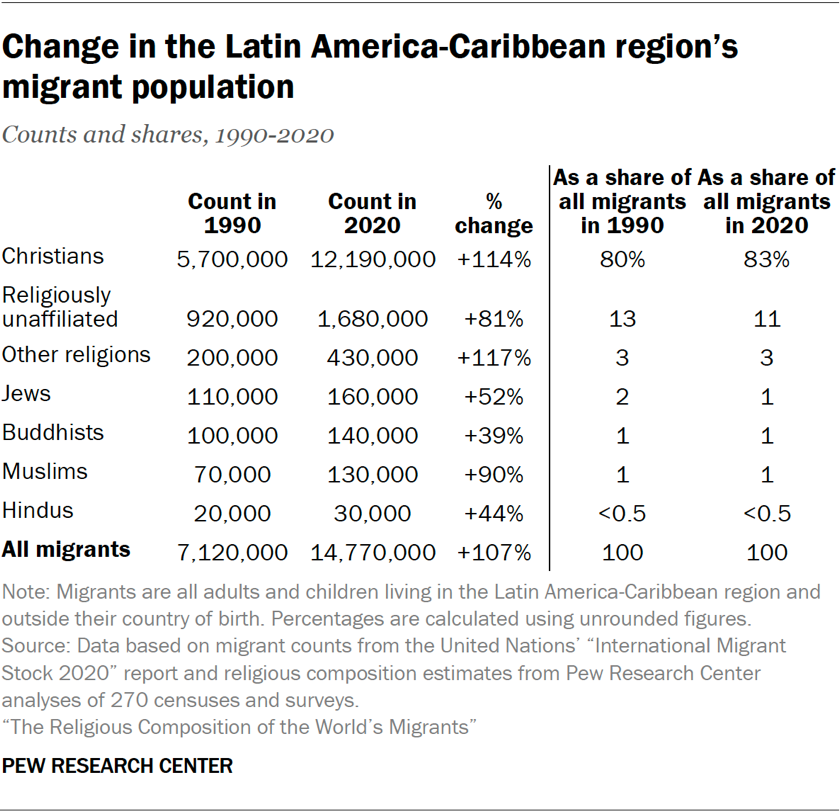

Latin America-Caribbean

International migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean have more than doubled over the past three decades, reaching nearly 15 million in 2020 (up 107%). During this time, the region’s overall population increased by 47% to 652 million.

Still, migrants made up just 2% of residents in the Latin America-Caribbean region in 2020, about the same as in 1990.

Much of the growth in the migrant population occurred between 2015 and 2020, as many Venezuelans escaped economic and political instability at home to settle in nearby countries.

The surge in migrants since 2015 is most apparent in the Christian population, partly because migrants from Venezuela are predominantly Christian.

The number of Christian migrants in the region has more than doubled since 1990, topping 12 million in 2020. Most were born in the region, and 9% were born in the U.S.

Religiously unaffiliated migrants living in Latin America increased by 81% since 1990 to reach a population of 1.7 million. Again, this growth was mostly the result of people leaving Venezuela.

Jews are the next-largest single group among migrants in the region, having grown by 52% between 1990 and 2020.

Since 1990, Buddhist migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean have grown by 39% to 140,000, Muslims by 90% to 130,000 and Hindus by 44% to 30,000.

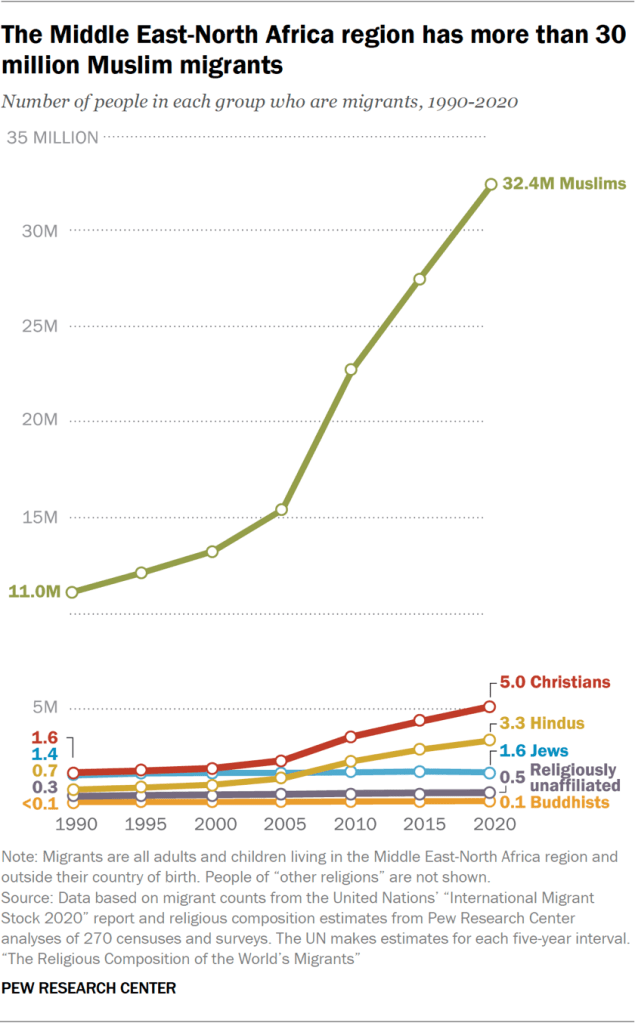

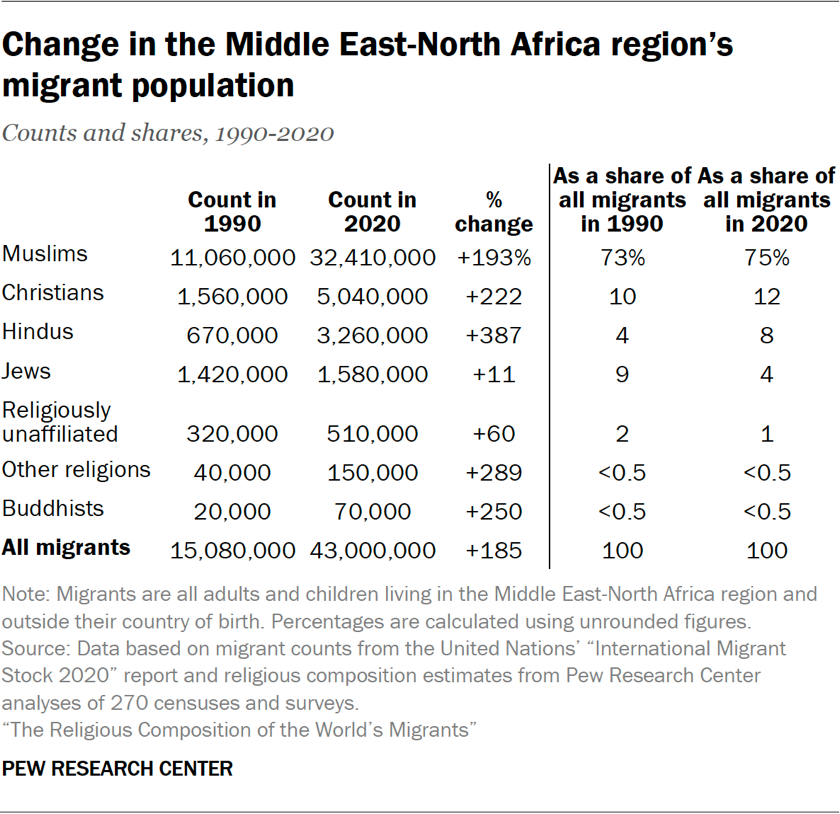

Middle East-North Africa

International migrants in the Middle East and North Africa have nearly tripled since 1990 (up 185%), reaching 43 million in 2020, while the region’s overall population almost doubled to 436 million (up 97%).

Migrants made up 7% of the region’s population in 1990 and 10% in 2020.

Roughly a quarter of the region’s migrants were born in India – the top origin country for several religious groups coming to the region.

Millions of others came from the Palestinian territories, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Syria.9 Some migration in the region is circular, with migrants moving back and forth to work and return home.

Most migrants living in the Middle East-North Africa region are Muslim. Since 1990, their number has nearly tripled, to about 32 million. India is the top country of origin for the region’s Muslim migrants, followed by the Palestinian territories and Bangladesh.

While India’s population is only 15% Muslim, migrants who leave India are disproportionately of minority religions, and most Indian migrants to the Middle East and North Africa are Muslim.

Christians make up the second-largest group of migrants in the Middle East-North Africa region. Since 1990, the region’s Christian migrant population has more than tripled, approaching 5.0 million.

As of 2020, almost a third of all Christians in the region live outside their country (or in some cases, territory) of birth. India is the largest source of migrant Christians in the region.

Hindus are the third-largest religious group among migrants in the region, having surpassed Jews by 2010. Hindus saw the largest percentage increase, multiplying almost five times since 1990, to over 3 million. The vast majority of Hindu migrants in the Middle East and North Africa have come from India, which is one of only two Hindu-majority countries in the world. (The other is Nepal, which was also a top origin country of Hindu migrants in the region.)

The stock of Jewish migrants in the Middle East-North Africa region increased by 11% to 1.6 million between 1990 and 2020. Israel is home to all but 60,000 of the region’s Jewish migrants. There was rapid Jewish migration to the area before and after Israel’s independence in 1948, and another major spurt took place after the collapse of the Soviet Union. More than 1 million people moved to Israel from the former Soviet Union between 1990 and 2017. But migration to Israel has slowed over time. Many of the migrants who came to Israel in recent decades are no longer living in the country due to death or subsequent migration to another country.

Religiously unaffiliated migrants in the region have grown by 60% over the decades, reaching an estimated 510,000 in 2020. Buddhist migrants have grown by 250%, yet total only about 70,000.

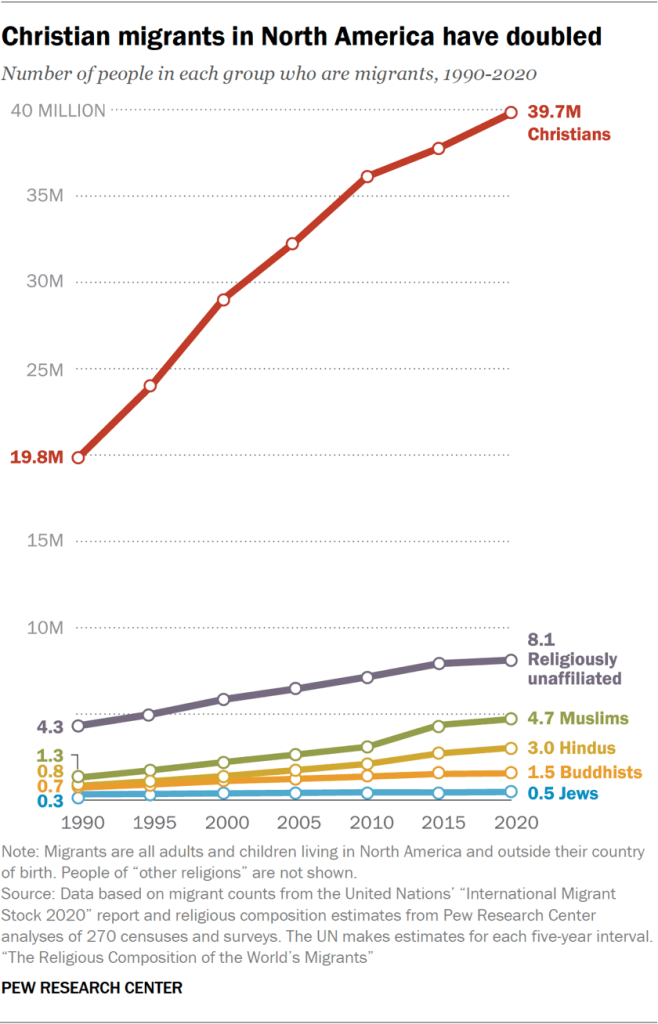

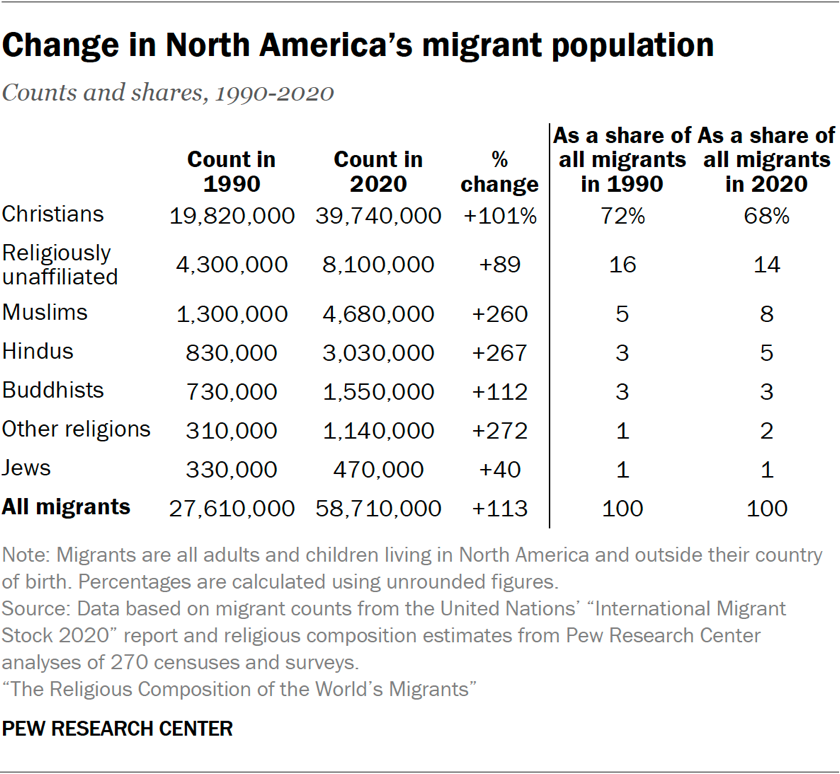

North America

International migrants in North America have more than doubled since 1990 (up 113%), approaching 59 million in 2020.

Overall, 374 million people lived in the region as of 2020, up 36% since 1990.

Migrants made up 10% of North America’s population in 1990 and 16% in 2020.

Most of these migrants live in the U.S. and Canada, which, when combined, have more migrants than all of Asia and the Pacific.

Nearly 12 million migrants living in North America were born in Mexico. That’s roughly triple the number from the next-largest origin country, India.

Christians make up around two-thirds of migrants in the region, down slightly from 72% in 1990. Yet the absolute number of Christian migrants living in North America has doubled since 1990, approaching 40 million in 2020.

More than a quarter of North America’s Christian migrants in 2020 – over 11 million – came from Mexico, up from 4.7 million in 1990. The region also saw sizable increases in Christian residents who were born in the Philippines, Guatemala and El Salvador – all Christian-majority countries.

The religiously unaffiliated make up the second-largest share of migrants in the region, as they do in the overall population. Religiously unaffiliated migrants grew by 89% to more than 8 million in 2020. Over 2 million unaffiliated migrants came to the region from China.

The stock of Muslim migrants in North America has risen by 260% to nearly 4.7 million as of 2020. Almost 600,000 of them came from Pakistan, while 490,000 came from Iran and 350,000 were born in Iraq.

In percentage terms, there has been a similar increase among Hindu migrants, who grew by 267% between 1990 and 2010 to just over 3 million. More than 2 million were born in India.

Buddhist migrants have more than doubled to roughly 1.6 million. More than 760,000 Buddhists living in North America were born in Vietnam, and 400,000 were born in China.

The stock of Jewish migrants in North America has increased the least, up 40% since 1990 to an estimated 470,000. There was a sizable wave of Jewish migration from the former Soviet Union to the U.S. and Canada from the 1970s through the 1990s, but it has been partially offset by deaths among prior generations of Jewish migrants from Europe, including many who lived in North America after escaping the Holocaust.

Sub-Saharan Africa

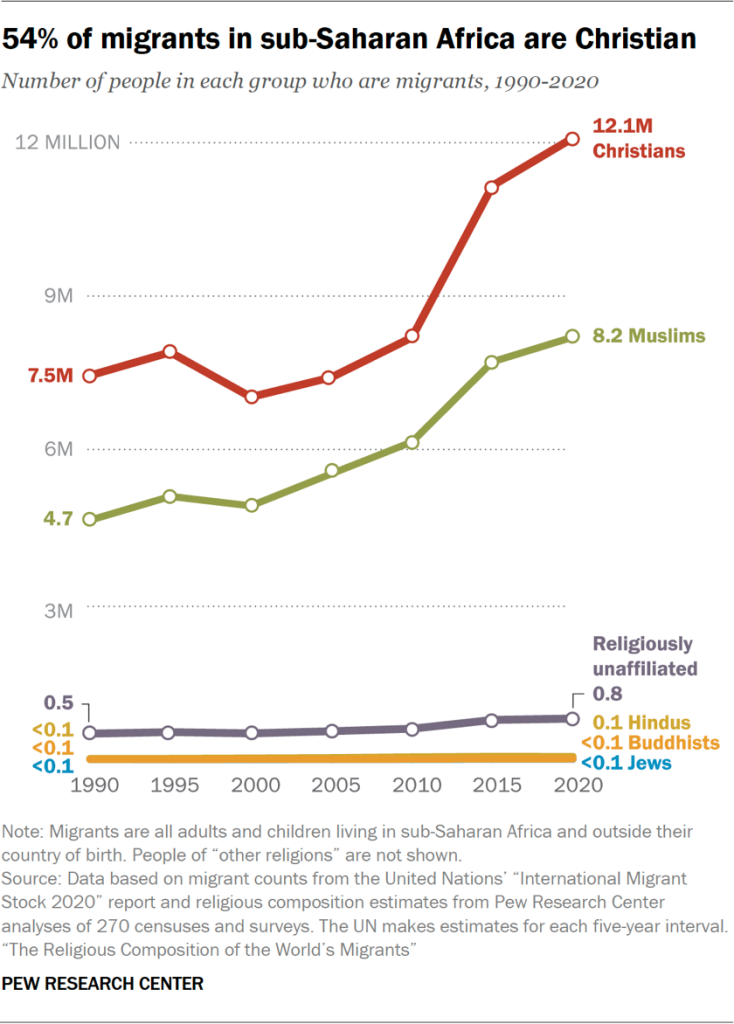

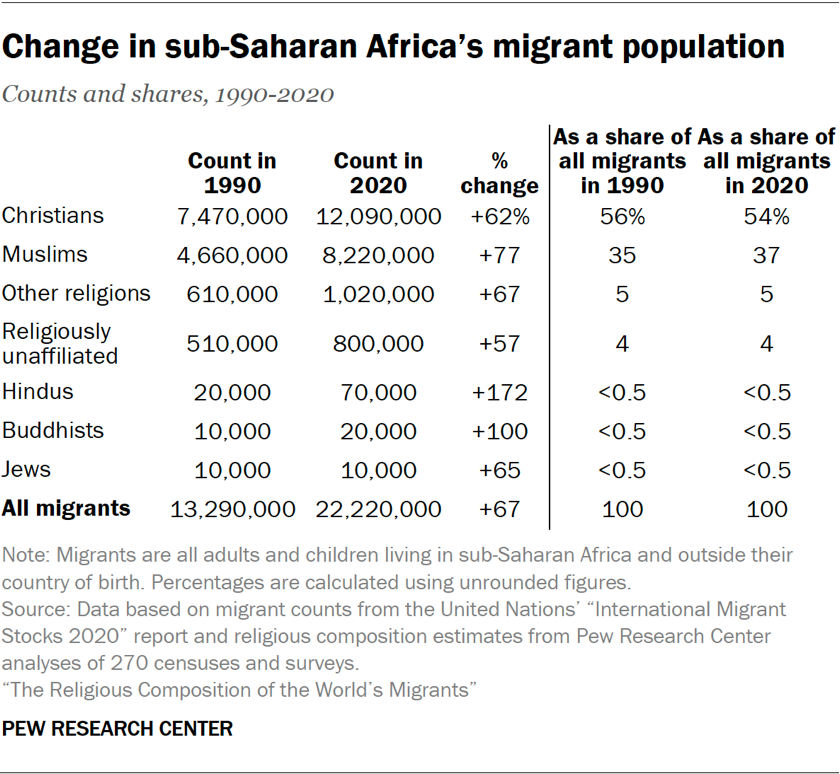

The migrant population in sub-Saharan Africa increased by 67% between 1990 and 2020 and now comprises more than 22 million individuals. Over the past three decades, the region’s overall population more than doubled to 1.1 billion, making it the second-most populous region in the world.

Migrants made up 3% of the regional population in 1990 and 2% in 2020.

Movement in sub-Saharan Africa has been driven by people fleeing armed conflicts and other forms of strife, particularly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan. But there has also been return migration to some countries. For example, the number of Rwandan and Mozambiquan migrants has declined after civil wars there ended in the early 1990s.10

Since 1990, the religious composition of migrants living in sub-Saharan Africa has been fairly stable.

As in most broad geographic regions in this study, Christians are the largest religious group among migrants in sub-Saharan Africa. The stock of Christian migrants in the region grew by an estimated 62% to more than 12 million between 1990 and 2020.

The most common origin countries for Christian migrants in the region are the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan.

Muslims are the second-largest religious group among migrants in the region, having grown by 77% to over 8 million in the decades since 1990. More than 2 million Muslims have left Burkina Faso and Mali, places where civilians are often the victims of fighting between government forces and Islamic insurgents.

Migrants in the “other religions” category have grown in sub-Saharan Africa by two-thirds since 1990, reaching 1 million in 2020. In this region, the “other religions” category includes many people who identify with traditional African religions. Burkina Faso is the most common origin country of migrants who identify with an “other religion.”

Hindu migrants are a small population in sub-Saharan Africa – constituting less than 0.5% of all migrants – but they have grown the most in percentage terms, rising 172% to 70,000.

Sub-Saharan African countries also host small populations of Buddhist and Jewish migrants. The Buddhist population has doubled since 1990 to reach 20,000, and Jewish migrants increased by 65% (though their numbers rounded to 10,000 in both years). While Buddhist migrants tend to come from Asian countries like China, Sri Lanka and Thailand, a large share of the Jewish migrant population came from Israel, and most now reside in South Africa.

Refer to our “Geographic spotlights” section for in-depth analyses of migration in Europe, GCC countries, India and the United States.