This methodology explains how we estimated the religious composition of foreign-born populations around the world. It describes the data sources we used to measure the number of migrants from each origin country living in each destination country, as well as the data sources and methods we used to estimate the religious composition of migrants.

A note on rounding: Throughout the report, we round counts of migrants to the nearest 10,000. All values below 10,000 are listed as “<10,000.” All percentages are based on unrounded figures.

UN migrant estimates

Counts of migrants for every origin-destination country pair come from the 2020 United Nations estimates of international migrant stocks. The UN provides estimates for 1990, 2020 and every five-year period in between (1995, 2000, etc.).

These estimates are based on censuses, population registers and nationally representative surveys, as well as statistics on refugees from international organizations. UN migrant counts are intended to include asylum-seekers, refugees and people in similar situations regardless of legal status.

All data comes from destination countries. (Most countries don’t have data on how many people born within their borders now live in each of the other countries of the world. However, they typically do have information on the number of people born elsewhere who now live within their borders.)

UN estimates of migrants are based on the best available data in each country, which may be incomplete.

For example, some countries have limited data on special populations, such as migrants without legal residence permits. In addition, many 2020 censuses or other data collection efforts were delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, so some 2020 estimates had to be based on extrapolation from earlier censuses or other sources.

For most destination countries, the UN relied on country of birth data to estimate how many people came from each origin country. However, in about 20% of countries, the UN’s estimates of foreign-born populations are based on measures of nationality rather than country of birth.

Nationality is not an ideal proxy for origin country, as some people migrate multiple times, and it is possible to be a citizen of a country one has never lived in.

The UN estimates include many people from miscellaneous “other” countries. Migrants can be categorized as being from an “other” country if the country they were born in no longer exists or if they are not sure where they were born. In other cases, receiving countries administer surveys with limited choices for origin country or collapse responses across many countries.

We distributed people classified as originating from an unspecified “other” country to known origins proportionately, so counts by origin in this report do not always match the UN’s original numbers. The largest number of migrants of known origins are from India, so we assigned the largest number of migrants of unknown origin to India, and so on. This is an imperfect solution but, for our purposes, an improvement to retaining the undifferentiated “other” origin that we cannot assign a religious distribution. We made one exception to this procedure: We excluded Vatican City as a destination because it hosted few migrants overall and zero migrants from known origins.

(Read more about adjustments to source data below. Refer to the UN’s own documentation for more information on the methods and limitations of migrant stock estimates.)

Pew Research Center religious composition estimates

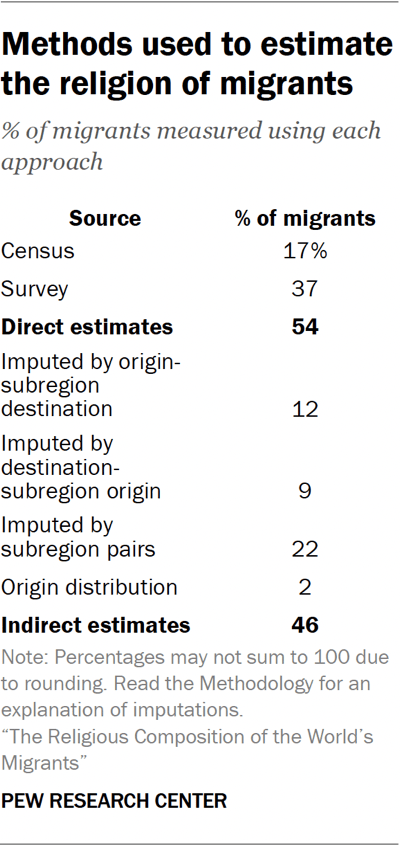

Religious distributions (i.e., the shares of people in each religious group) are based on our analysis of censuses and surveys of migrants by origin-destination country pair. Available survey and census data directly provides religious composition data for more than half of the world’s migrant population (54%) as of 2020.

To be included among our sources, censuses and surveys must have data on:

- The origin of migrants, based on a question about a respondent’s country of birth (preferred) OR a migrant’s nationality (used rarely when country of birth was not asked)

- The religious affiliation of migrants

Since censuses aim to cover entire populations, they typically provide data about many more migrants than surveys do. For this reason, we generally prefer censuses over surveys. Whenever possible, we relied on a single census for information about both country of origin and religious affiliation. When more than one census was available, the census nearest the midpoint of the study period was used because this report assumes that religious compositions are stable across time. (Read the section on the study’s time frame for more on this assumption.)

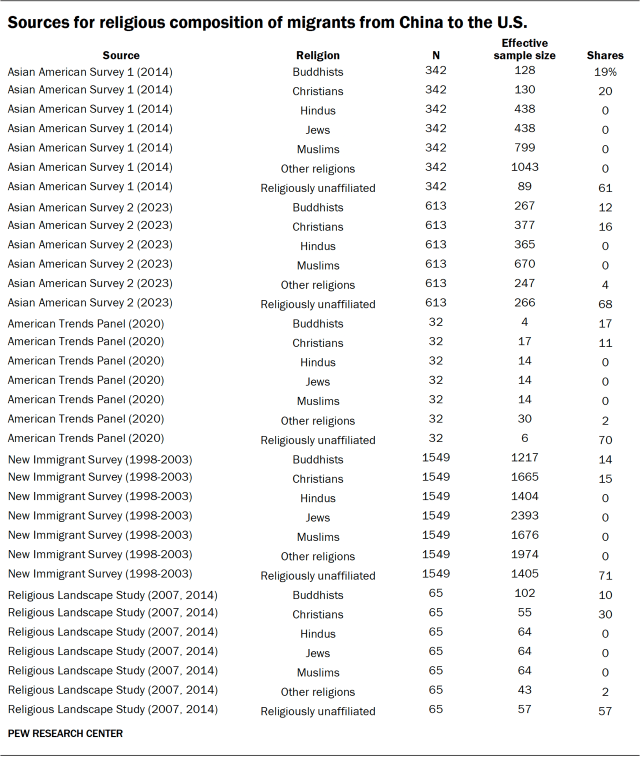

When census data was unavailable, religious distributions were calculated based on surveys measuring both religion and country of origin. In cases where multiple surveys (but no censuses) were available, we analyzed each survey and then aggregated their results by the effective sample size of migrant populations, using respondents in each origin-destination country pair to calculate these averages. (An effective sample size is calculated by dividing the total number of survey participants by the survey’s design effect, which reduces sample size based on how much the survey design relied on weighting to achieve a representative sample.)

The United States is an example of a destination country for which we often relied on weighted averages of multiple estimates. The table below shows the sample size, effective sample size and religious distributions among adults for one example migrant origin-destination country pair: China to the U.S. For this origin group, the New Immigrants Survey had the largest effective sample size and therefore the greatest influence on the average religious distribution we used to represent the China-to-U.S. origin-destination pair.

We used a threshold of 50 cases (based on effective sample size) to include the religious distributions of country pairs at the global or regional level and a threshold of 100 cases to discuss individual country pairs. For example, we include migrants from the United Arab Emirates to Egypt in estimates of the religious composition of people who migrate globally and within the region, but results for this specific country pair are not presented in the report because they are based on religion responses from only 54 individuals. On the other hand, over 1,000 people who have migrated from Iraq to Egypt provided their religious affiliations, so we report that this group of migrants is 99% Muslim, in addition to including them in global and regional estimates.

Adjustments to census and survey data

Sometimes, censuses and surveys did not provide religious composition information that fit our analytical framework, requiring us to make adjustments to the source data.

This report sorts migrants into seven groups for analysis: Christians, Muslims, the religiously unaffiliated, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, and an “other religions” category that is intended to include only people of religious groups with insufficient data to analyze separately. However, some censuses and surveys use a multiple-choice question for religious affiliation that does not offer all of these response options. Instead, religions without many adherents in a destination country are sometimes not listed as possible answers, and people who identify with them are placed in an undifferentiated other category even though they follow a religion we analyze separately.

When necessary, we distributed people from undifferentiated categories to major religious groups. Because countries tend to include response options for religions that are relevant in their context, these adjustments could have affected estimates for fewer than 1% of migrants.

The 2006 Egyptian census, as one example, does not include Buddhist, Hindu or “no religion” as response options to the religious affiliation question. Census takers must identify as Muslim, Christian, Jewish or “other.” According to this source, Egypt’s population is overwhelmingly Muslim and Christian. There were enough migrants in Egypt in 2006 from China, India, Japan and the Netherlands to analyze whether they identified as Muslim, Christian, Jewish or with another religion in the census. Each of these origin countries have large populations of Buddhists, Hindus and/or unaffiliated people. For example, 80% of Indians in India are Hindu, so we would expect many people who have migrated from India to Egypt to be Hindu. Without a Hindu response option, it is impossible to tell how many migrants from India who marked “other” on the Egyptian census are Hindu instead of members of a smaller religious group (such as Sikhism or Jainism). In cases like these, when we had good reason to think that people were included in an undifferentiated other category despite belonging to one of the groups we analyzed separately, adjustments were made based on the religious composition of the origin country.

In the India-to-Egypt example, “other” responses in the census were redistributed to Buddhist, Hindu, unaffiliated or “other religions” proportionate to those religions’ shares in India, the origin country. Among Indians in Egypt, half indicated on the census that they were Muslim (while Muslims make up a considerably smaller 15% of all people living in India) and 18% said they were Christian (but Christians account for only 2% of India’s population). About a third of respondents from India chose “other.” Those remaining “other” responses were distributed according to the groups’ sizes among Indians remaining in India. Based on this procedure, we estimate that 30% of migrants to Egypt from India are Hindu (compared with 79% of those in India), 1% are members of “other religions” (2% in India are), and fewer are Buddhist.

Like some religious affiliations, some origin countries are not measured directly and instead recorded broadly as “other.” This can happen for a variety of reasons, like if a census offers a non-exhaustive list of countries to choose from, if participants list an origin that is not a country, or if they were born stateless. Rather than retain an undifferentiated other origin, we distributed those with missing origins proportionately to known countries of origin. This had the effect of inflating the numbers provided by the UN for specific countries because the UN data maintains an undifferentiated other category.

Census of Israel

We made additional religious composition adjustments using public data files from the 2008 census of Israel.

Public data from this census collapses most countries into regions or smaller groups. Using this aggregated information, we distributed migrants to the countries within that group and applied the group’s composition to each of the countries. For example, the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand are all included in the category of North America and Oceania. We applied a single religious distribution from this source for all North American origins to every country in the group.

UN estimates show that 30% of migrants to Israel are from unclassified “other” origin countries. Based on the 2008 census data, the UN data seems to have substantially underestimated the number of migrants from former Soviet Union countries. We proportionately distributed migrants from “other” origins to match the census data’s estimates of migrants from the former USSR.

Israel maintains a government database with information on the religion of residents ages 16 and older. Adult religion information in data files from the 2008 census comes from this government database rather than a direct measure of religion in the census. We requested more detailed data on the origins of migrants from the Central Bureau of Statistics, but this request was denied.

Other limitations of survey data

As noted above, surveys have smaller samples than censuses and they are less reliable for measuring small populations, including migrants from specific origin countries. In some cases, surveys are administered in only one language and some migrants may not have the language proficiency to participate. Because such surveys are biased toward including migrants who have been in a destination country for a longer period, they may also include migrants who are more likely to have assimilated in other ways, including religiously. In fewer cases, surveys lean in the other direction, with only recent migrants as respondents. U.S. religious composition estimates draw on both types of surveys.

The Center’s Religious Landscape Study (conducted in 2007 and 2014) was only offered in English and Spanish, excluding potential survey respondents who do not speak either language, and the 1998-2003 New Immigrant Study only includes recent migrants to the U.S. It was conducted in 19 languages.

Why our estimates may differ from other sources

This report is based largely on information about international migration published by the United Nations in December 2020. As a result, some figures in this report differ from statistics collected in national censuses conducted after 2020. In many cases, the differences are small, but in some cases they are considerable.

For example, our estimate of the Jewish immigrant population in the United Kingdom (approximately 120,000) seems high in comparison with newly released data from the 2021 census of England and Wales, which counted 53,942 foreign-born Jews.

There are similar discrepancies between our migration estimates and the latest census numbers for some other religious groups and in some other countries. For example, Australia’s 2021 census counted more foreign-born Hindus (547,032) and fewer foreign-born Muslims (487,426) than our estimates of those groups as of 2020 (460,000 Hindus and 530,000 Muslims).

Generally speaking, national censuses are the most accurate source of data on population sizes. Our estimates are not intended to replace, or to challenge, the highly detailed information emerging from national statistical bureaus based on high-quality censuses.

However, there are several reasons why our estimates are not always the same as what national censuses produce. One factor explaining variation in 2020 numbers is that we have relied on the UN’s estimates of the total number of international migrants living in each country as of 2020. Because the UN published estimates in 2020, their demographers, in turn, relied on the census and survey data available to them at the time, most of which was collected before 2020; in some cases, they may have used data from the 2010 round of decennial (every 10 years) censuses or even earlier.

In addition, the UN seeks to include all migrants, regardless of their legal status. Some countries use different definitions of who counts as a migrant; for example, some countries do not count naturalized citizens as international migrants. In the case of the United States, the UN considers people born in Puerto Rico who now live in the 50 states and the District of Columbia to be international migrants, while the U.S. Census Bureau does not.

As the UK’s Office of National Statistics has cautioned, “Different data sources collect and use the measures country of birth, nationality, and passports held in different ways. This leads to inevitable differences in the statistics produced from each data source. However, all of these statistics are reported under the term ‘international migration,’ which can lead to confusion.”

Further, Pew Research Center’s estimates of religious affiliation are based, ideally, on the way people would answer a single question: “What is your current religion, if any?” Some countries include this kind of question in their national censuses, but many (including the U.S.) do not. And some countries that collect data on the religion of their inhabitants do not make it public.

Where censuses do include a religion question, it is sometimes labeled as optional, and some people choose not to answer. For example, 11% of migrants from Israel chose not to answer the religion question in the most recent census of England and Wales. Our estimates assume that the Israeli migrants who don’t answer the question have the same mix of religious affiliations as the Israeli migrants who do answer the question.

When we estimate the religious identification of migrants around the world, we try to do so using transparent, consistent and comparable methods (described in detail elsewhere in this Methodology) for nearly 100,000 combinations of origin and destination countries. To do this, we make some assumptions, one of which is that the religious mix of people who move from Country A to Country B is fairly constant over time. In reality, though, this mix may change. For example, the proportion of all Poland-born migrants living in the UK who are Jewish may have been higher in the 1980s and 1990s (when more Holocaust survivors were still alive) than in 2010 or 2020.

For all these reasons, our estimates of the religious makeup of immigrants in particular countries sometimes differ from what the latest national census or survey has produced. We do not claim that our figures are better than any other source. The main advantage of our estimates is that they are truly global, allowing for comparisons between countries and revealing broad patterns that would not be identifiable from any single country’s own census or surveys.

Estimating religious compositions when no census or survey data is available

Direct estimation: For more than half of the world’s migrants (54%), we were able to use census or survey data to directly estimate their religious compositions. Census data was used to measure 17% of migrants and survey data was used for 37% of them.

Indirect estimation: In the vast majority of remaining cases (46% of all migrants), there was not sufficient census or survey data providing respondents’ origin and religion variables, so we used censuses and surveys to indirectly estimate migrants’ religious compositions, following one of three approaches.

First indirect estimation approach: Origin-subregion destination

When possible, we imputed religious compositions of missing country pairs by substituting the composition of migrants from the same origin country to the same subregion – a group of countries that share similar geographical and religious contexts. This origin country-to-subregion destination method was used to estimate the religious composition of 12% of global migrants.

To be considered similar in this way, countries had to be in the same geographic region and share the same largest religion. Fourteen of these contexts or subregions were used for imputation, including country groups like Buddhist plurality Asia and Christian plurality sub-Saharan Africa.

As an example, available survey data includes no one who migrated from the U.S. to Spain, so we cannot directly estimate the religious composition for this country pair. Instead, we applied the religious distribution of people from the U.S. to all European countries in which Christians are the largest religious group.

Second indirect estimation approach: Destination-subregion origin

If estimates could not be computed using country of origin and subregion destination, we were sometimes able to impute based on the religious composition of migrants from the same origin subregion to the country of destination. We used this method for 9% of migrants.

Third indirect estimation approach: Subregion pairs

In many other cases, there was no data on people from a specific origin country to a destination subregion, nor from an origin subregion to a destination country. Under these circumstances, we estimated the religious composition of migrants based on their origin and destination subregions. We relied on subregion pairs to estimate the religious composition of 22% of migrants.

For example, we have data on too few people who have migrated from the U.S. to Bangladesh to estimate their composition. There are also not enough cases of people born in the U.S. who have migrated to Muslim plurality Asia to substitute that distribution; nor is there sufficient data on migrants from Christian plurality North America to Bangladesh. Instead, we estimated the composition of these U.S.-to-Bangladesh migrants using the average distribution of all people with Christian plurality North America origins to all Muslim plurality Asia destinations.

Country of origin religious composition: For rare cases that could not be directly or indirectly estimated or imputed, we estimated the religious composition of migrants based on the religious composition of the origin country, relying on the Center’s earlier work estimating the religious makeup of every country in the world. This procedure was used to estimate the composition of 2% of the world’s migrants. In these cases, we applied our previous religious composition estimates for the year 2010.

Missing data for destinations in the Middle East-North Africa region was common, particularly among Gulf Cooperation Council countries. We conducted thorough searches for data and contacted several statistical agencies in the region but only turned up sufficient data from two countries: Egypt and Israel. Because Israel represents a very different religious context, estimates for most Middle East-North African countries rely on Egypt as a proxy.

Evaluation and adjustment of proxy estimates

In cases where we estimated migrant religious composition using the indirect methods described above, we evaluated these indirect estimates against our knowledge of migration dynamics in destination countries and against our preliminary estimates of the total size (i.e., migrants and nonmigrants combined) of religious minority populations in destination countries. Most results generated by our indirect estimation procedure seem reasonable based on the information available to us.

However, our indirect estimates of the number of Christians among European migrants to Turkey and among migrants from South Sudan to Sudan required adjustment. We manually lowered estimates of the Christian share of migrants in these two countries. Our indirect procedures were not able to capture the predominantly Muslim composition of migrants coming to Turkey from nations in Europe or the distinct pattern of migration by religion that has resulted from political divisions in Sudan and South Sudan.

Religious compositions of overall populations

To provide context for estimates of the religious composition of the world’s migrants, we use provisional Pew Research Center estimates of overall religious compositions in 2020, including nonmigrants. This report was published in advance of a forthcoming Center report that will contain new estimates of the overall religious composition of each country. These forthcoming 2020 estimates will incorporate census and survey data collected and released on a delayed schedule because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The provisional numbers for the global distribution of religions shown in this report are based on a mix of three primary sources.

First, for most countries, we use population projections for the year 2020 made for our 2015 report “The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050.”

Second, for the U.S., we use estimates produced for our 2022 report “Modeling the Future of Religion in America.”

Third, for China, we use estimates based on analysis described in our 2023 report “Measuring Religion in China.” Our 2020 estimates for China, which use data from the Chinese General Social Survey, rely on a zongjiao measure of religious identity that allows us to track changes in China’s religious landscape. This approach represents a significant change from our prior approach to measuring religion in China. We compare the approaches in the methodology of our China report.

The largest differences between the provisional total population figures used as context in this report and our previously published global estimates result from the aforementioned changes in our approach to measuring religion in China. The provisional figures used in this report differ from estimates we will publish in our forthcoming report, which will reflect careful attention to the full range of data now available to measure the overall 2020 religious landscape in every country.

Study period

Pew Research Center is tracking changes in the religious landscape around the world. A contribution of this report is to explain how changes in migration patterns contribute to religious change. For example, we reveal that the migrants living in one country often have a mix of religious identities that varies significantly from their home country, such as the greater incidence of Muslims among Indian-born people living in Egypt compared to India’s population. Furthermore, our data shows how change in the makeup of origin countries over time has led to changes in the religious composition of migrants.

This report pushes the limits of what we can know using direct and indirect methods to analyze available data. Therefore, we make an important simplifying assumption – that the religious makeup of people who move from country A to country B was constant between 1990 and 2020. Of course, reality is more complex. There have been some changes over time in the religious composition of migrants between pairs of countries. But we didn’t have adequate data to track such within-country pair change in the overwhelming majority of cases. Instead, this report captures the cumulative change happening at the country and regional levels to migrant stocks as a result of changing patterns of movement between countries.

In the cases when more than one census was available, we relied on the census conducted closest to the midpoint of the study (2005).

Similarly, many distributions are derived by aggregating multiple surveys conducted anytime during the past several decades. Survey samples were often too small to separate, and we chose to maximize the number of country pairs extracted from survey data rather than applying distributions only to the period in which data was collected. Consequently, estimates of changes in the composition of migrants are largely driven by migratory shifts from origin countries, not changes in the religious composition of specific origin-destination pairs. For example, in the U.S., the changing estimate of the religious composition of migrants over time reflects the growing share of migrants from Asian countries, but it does not reflect changes within the religious composition of migrants from Mexico over time. If this report focused only on a data-rich country with large migrant populations like the U.S., our approach might have been different. The approach we took was made based on the limitations of available global data.

Furthermore, since we focus on migrant stocks, changes in the religious composition among recent migrants may slowly affect the average composition of an origin country population that includes people who have been in the destination country for many years.

A modest share of migrants may change their religious affiliation after entering destination countries.30 Religious change may be more common among locally born children of immigrants, who are not migrants.

Distance analysis

The analysis of average distance traveled by migrants is based on the distance between the center of the origin country and the center of the destination country. These distances might not be the exact average miles traveled by migrants between origin-destination pairs, but available data does not include city-specific origins and destinations. For example, the analysis assumes that Mexican migrants to the U.S. originated in the center of Mexico and moved to the center of the U.S. In reality, a disproportionate share of these migrants may have originated and settled near the United States’ southern border. However, there are also many cases in which migrants traveled farther than the distance from one country center to the next, like from southern Mexico to the northeastern U.S.

‘Faith on the Move’

This report is the successor to “Faith on the Move: The Religious Affiliation of International Migrants,” our report on this topic published in 2012.

There are important methodological differences between the two efforts. This report describes change over time while the previous provided a single snapshot.

Whereas this report relies on the UN’s estimates of migrant counts, “Faith on the Move” made its own estimates of the size of the migrant population by country pairs because, at that time, the United Nations did not publish extensive estimates of the migrant stocks in each country from each source country.

When multiple surveys but no censuses are available, this project combines all available survey estimates and presents a weighted average distribution. “Faith on the Move” relied on the single best source for each origin-destination pair.

Finally, this report replaces missing country pair data with religious distributions for the origin and destination subregions when possible. “Faith on the Move” instead substituted the origin countries’ religious distributions in every case of missing data.