Annual report includes a five-year look at the relationship between religion-related government restrictions and social hostilities in each country

This is the 15th in a series of annual reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. This analysis was produced by Pew Research Center as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation (grant 63095). This publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation.

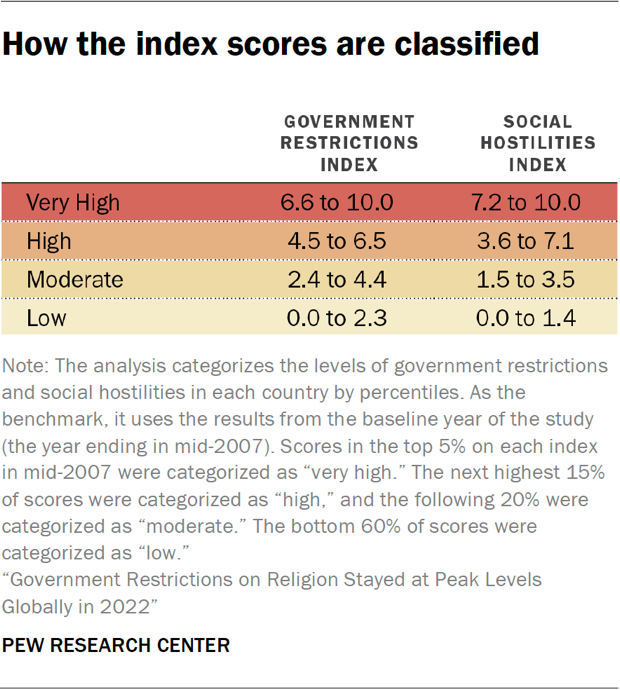

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2022 – the most recent year for which data is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by governments to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons and other forms of religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. State Department’s annual “Reports on International Religious Freedom” and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (Refer to the Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

To learn more about the analysis for understanding the relationship between GRI and SHI scores, read the Methodology.

Since 2007, Pew Research Center has analyzed religious restrictions in nearly 200 countries and territories around the world with two measures that are related but that also are very different: the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and the Social Hostilities Index (SHI).

The GRI measures restrictions by governments that can target people for their religious beliefs, as well as incidents in which governments use religious justifications to harass, intimidate or restrict people. The SHI, on the other hand, looks at religion-related hostilities by nongovernmental actors (i.e., private individuals and social groups).

In 2022, the global median scores on both indexes stayed the same as they were in 2021, at 3.0 out of 10.0 on the Government Restrictions Index (its peak level) and at 1.6 out of 10.0 on the Social Hostilities Index.

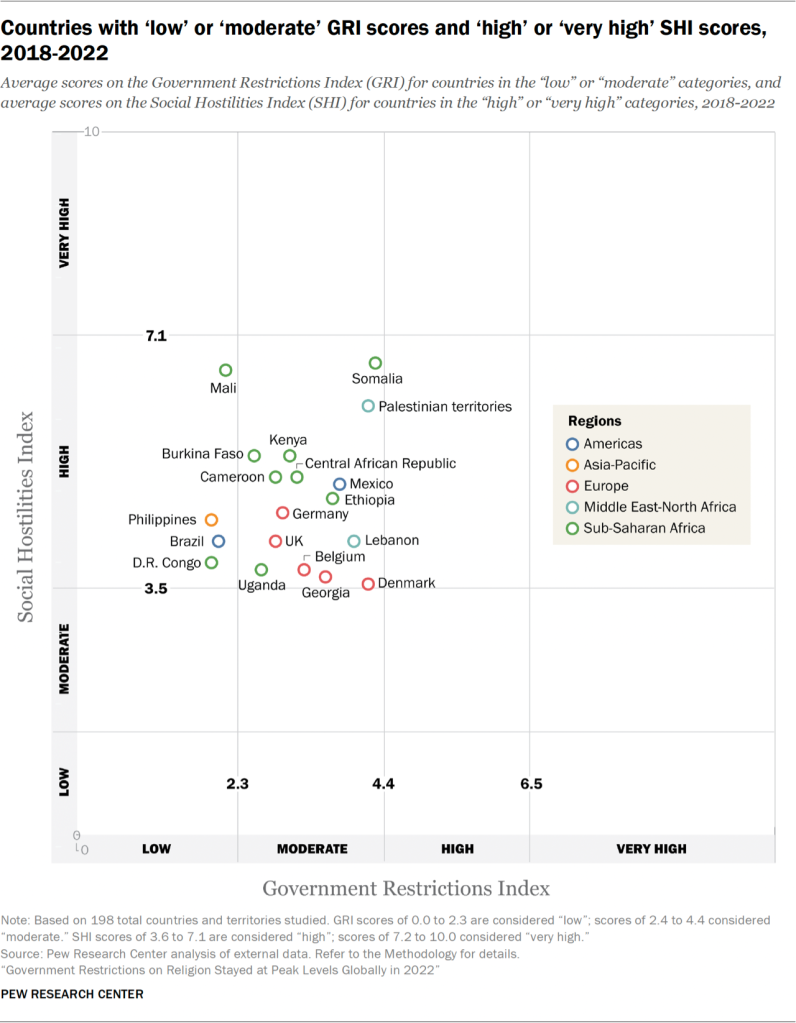

This is the Center’s 15th annual study of restrictions on religion. Before examining the 2022 findings in detail, we begin by examining the general relationship, in all countries, between levels of government restrictions and levels of social hostilities over the last five years of the study (2018 through 2022).

In simple terms, the question we are asking is: Do countries in which government authorities pressure religious groups also tend to be places in which social groups and individuals are hostile toward religious groups? Similarly, do countries with relatively few government restrictions on religion also tend to be places with relatively few social hostilities involving religion?

For the most part, the answer is yes: Government restrictions and social hostilities tend to go hand in hand. Over the five-year period, roughly three-quarters of all countries had either “high” or “very high” levels of both kinds of restrictions, or they had “low” or “moderate” levels of both kinds of restrictions. However, there are a sizable number of exceptions: About a quarter of all countries were in the high/very high range on one index and the low/moderate range on the other index.

Here is a breakdown:

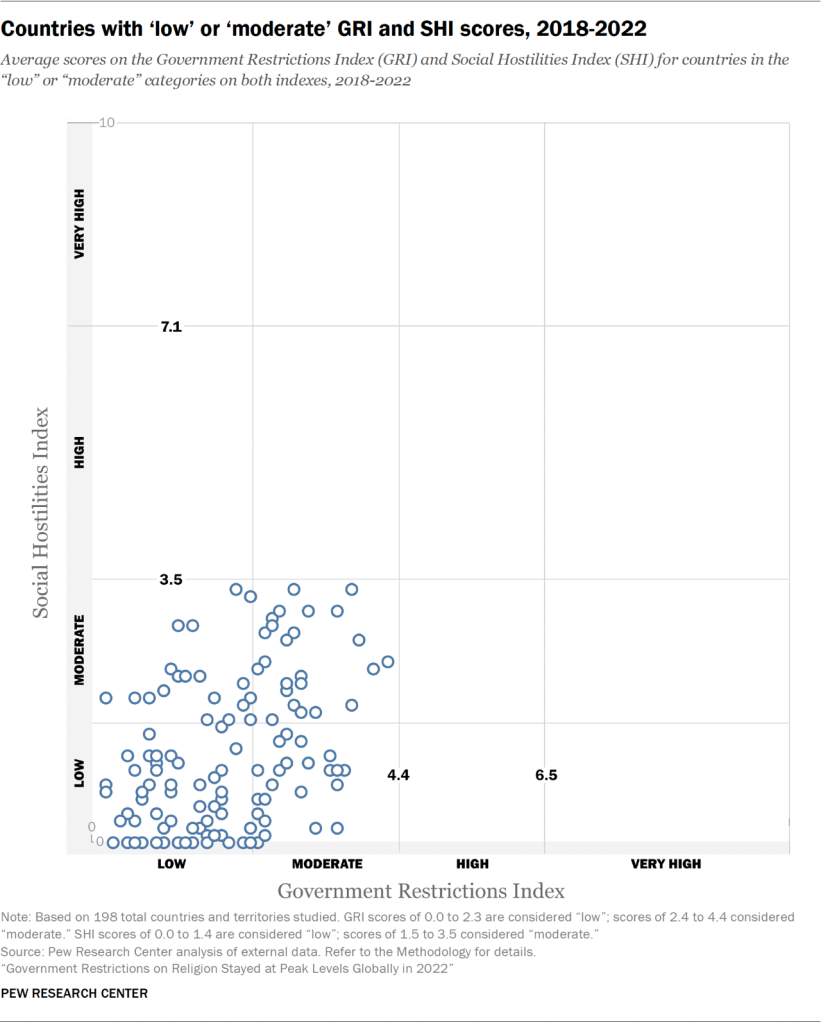

- 62% of the countries and territories analyzed (123 out of 198 studied) had low or moderate GRI scores and SHI scores, on average, from 2018 through 2022. For example, South Korea, Canada and the United States are among these countries.1

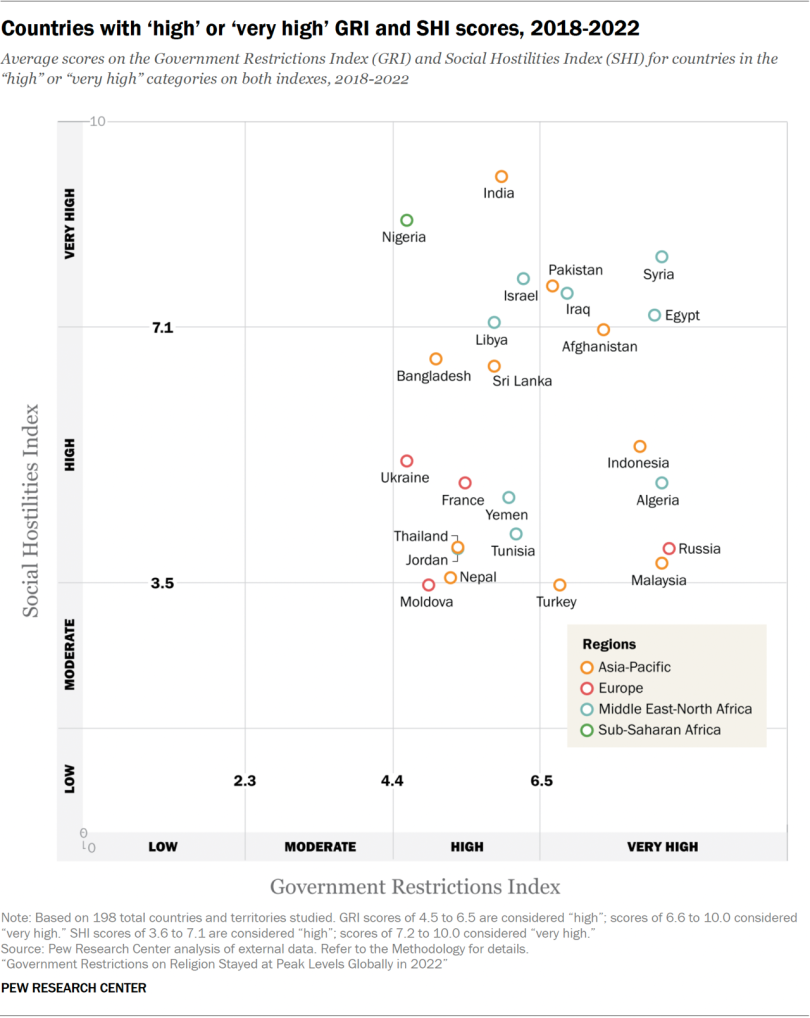

- 12% (or 24 countries) had high or very high GRI scores and SHI scores, on average, in the same five-year period. Egypt and India are among these countries.

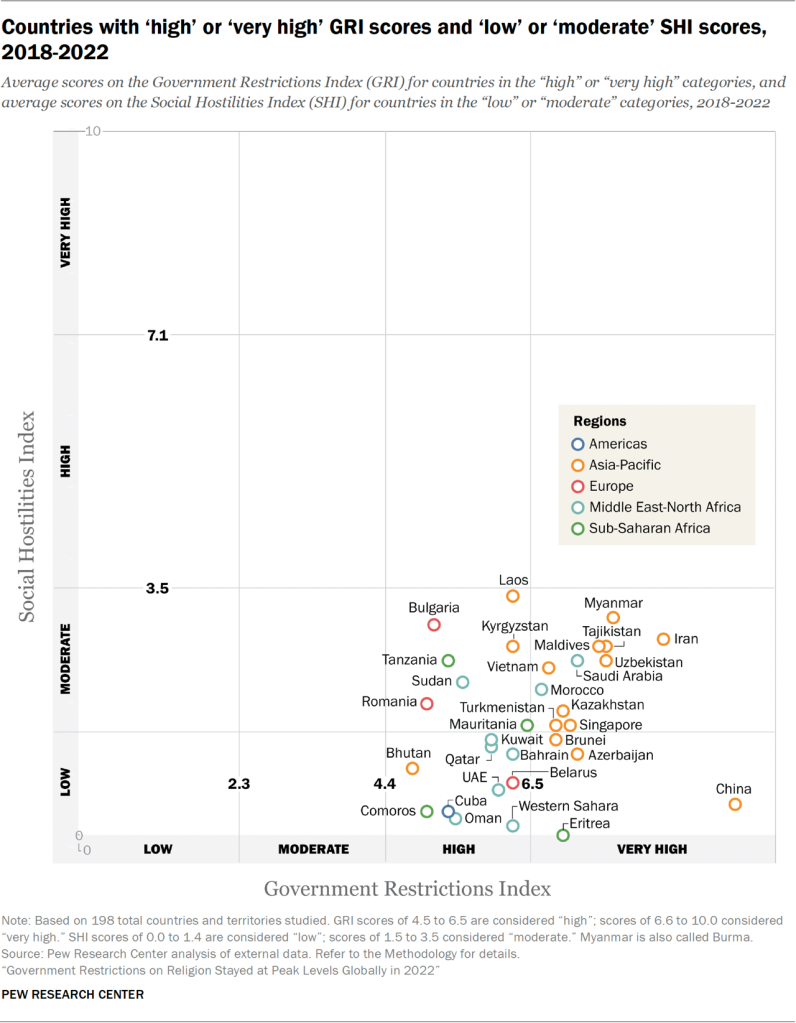

- 16% (or 32 countries) had high or very high GRI scores but had low or moderate SHI scores. China and Cuba are among these countries.

- 10% (or 19 countries) had low or moderate GRI scores but were in the high or very high range of SHI scores. Brazil and the Philippines are among these countries.

- Most countries that had high or very high GRI scores nevertheless had low or moderate SHI scores (32 of 56 countries, or 57%).

Researchers looked at mean (i.e., average) GRI and SHI scores over the most recent five years of the study (2018-2022). This multiyear analysis reduces the impact of the year-to-year fluctuations that occur in the index scores of many individual countries, and thus offers a more stable set of scores.

Background on the study

Since 2007, Pew Research Center has been tracking restrictions on religion on two 10-point indexes:

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI): Government restrictions on religion include laws, policies and actions that regulate or limit religious beliefs and practices. They also include policies that single out religious groups or ban particular beliefs or practices; the granting of benefits to some religious groups but not others; and bureaucratic rules that require religious groups to register to receive benefits.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI): Social hostilities include actions by private individuals or groups that target particular religious groups, often minorities. They can involve religion-related harassment, mob violence, terrorism and militant activity, as well as hostilities over religious conversions or the wearing of religious symbols and clothing.

Countries with low or moderate scores on both indexes

A majority of countries (123 out of 198 studied, or 62%) have scored in the “low” to “moderate” range on both the GRI and the SHI, on average, from 2018 through 2022. Nearly all countries in this group (121 out of the 123) have populations under 60 million, including South Korea, Canada and Ghana. In 34 of these countries, the population is under 1 million.

(Among the 34 countries with fewer than 1 million people, nine had mean SHI scores of 0.0 out of 10.0, meaning that from 2018 to 2022, no social hostilities were recorded for those countries. These countries include the small island states of Palau and Nauru. In addition, three countries with populations over 1 million – Botswana, Namibia and Lesotho – also had a mean SHI score of 0.0 during this period.)2

Looking regionally, 32 of 35 countries in the Americas had low or moderate scores on both scales in 2022, compared with 33 of 45 countries in Europe, 34 of 48 in sub-Saharan Africa, and 24 of 50 in the Asia-Pacific region. No countries in the Middle East-North Africa region had low or moderate scores on both the GRI and SHI.

In general, countries with low to moderate levels of government restrictions were somewhat more likely than other countries to also have low to moderate levels of social hostilities.

Countries with high or very high scores on both indexes

Two dozen countries fell into the high or very high GRI and SHI categories in terms of mean scores from 2018 through 2022.

Many of these countries experienced religion-related wars, militant activity or ongoing sectarian violence. For example, sectarian tensions and violence have been reported in multiple years during this period in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Iraq, Israel, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Syria, Thailand and Yemen.

In Thailand, for instance, a yearslong conflict continued in 2022 in the Deep South region, where attacks by “suspected insurgents” fueled tensions between ethnic Malay Muslims and ethnic Thai Buddhists, according to a U.S. State Department report on human rights practices. Martial law has been in effect in the southern provinces since 2006, shielding state security forces from accountability, and there have been multiple reports of excessive force by the military when conducting raids or arresting people. One such case involved an ethnic Malay Muslim rubber farmer who died in military custody in 2019 after being accused of taking part in the insurgency, according to Human Rights Watch.

Also in this category are a handful of countries in South Asia that, for many years, have had religion-related violence by nongovernmental actors while also having high or very high government restrictions. India and Pakistan, for example, have had high or very high GRI and SHI scores every year since the study began in 2007, while Bangladesh has had high or very high scores in most years. (For more details on 2022 events in India and Pakistan, read Chapter 3.)

Nine out of the 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region also are in this category, including Iraq and Syria (for details on events in these two countries, jump to Chapter 3). By comparison, 10 of the 50 Asia-Pacific countries and four of the 45 European countries have been in the high or very high range on both indexes, on average, from 2018 through 2022. Just one of the 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa fell in these categories during that time span, and none of the 35 countries in the Americas did.

Countries with high GRI scores and low or moderate SHI scores

Among the 198 countries and territories analyzed in the study, 32 had high or very high levels of government restrictions while also having low or moderate levels of social hostilities from 2018 to 2022.

Of the countries in this category, more than two-thirds (or 22 out of the 32) are classified as authoritarian on the 2022 Democracy Index of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).3 Most of these countries (20 of the 32) also have governments that give preferential treatment to certain favored or official religions. And nine of the 32 have governments that our analysis classifies as being hostile to religious institutions more generally.4

There were no countries in this subset that were classified by the EIU as “full democracies.”

The prevalence of authoritarianism among countries with high or very high government restrictions was explored in a previous Pew Research Center analysis of GRI and SHI data from 2018. The pattern found in the present study is that countries displaying a combination of high or very high levels of government restrictions and low or moderate levels of social hostilities tend to have authoritarian governments, give preferential treatment to one or more religions, or have a general hostile relationship toward religious institutions. Such regimes may tightly control religion as part of broader restrictions on civil liberties.

Countries with high GRI scores and low or moderate SHI scores include post-Soviet states classified as authoritarian by the EIU, including Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. All have been classified in a previous Pew Research Center analysis as having a “hostile” relationship toward religion.

China, Cuba and Vietnam also are authoritarian regimes (according to the Economist’s classification) that have high or very high GRI scores but are in the low or moderate range of social hostilities. All three governments also are generally hostile toward religious institutions, according to the previous Center study.

China, which bans religious and spiritual “cults” whose popular followings might pose a challenge to the ruling Chinese Communist Party, has had very high GRI scores every year since the inception of the study, along with low or moderate levels of social hostilities in most years. In Cuba, the government targets Christian leaders who oppose the ruling Cuban Communist Party. Cuba has had “high” government restrictions in most years of the study, but low social hostilities in almost all years.

Another country with this combination of high GRI and low or moderate SHI scores is Singapore, a small but religiously diverse country that is classified as a “flawed democracy” by the EIU. Singapore has had high or very high GRI scores, along with low or moderate SHI scores, in nearly all years of the study dating back to 2007. While Singaporean officials have repeatedly said that the country is committed to a multiracial and multireligious society marked by “religious harmony,” restrictive policies toward some religious groups – such as a ban on Jehovah’s Witnesses – have driven up Singapore’s GRI scores.

Most countries with high GRI scores and low or moderate SHI scores are located either in the Middle East-North Africa region (9 of the region’s 20 countries fall into this category) or the Asia-Pacific region (15 of 50 countries). Fewer countries in Europe (3 of 45), sub-Saharan Africa (4 of 48) or the Americas (1 of 35) are in this category.

Countries with high SHI scores and low GRI scores

Of the 198 countries and territories studied, 19 had high or very high SHI scores while scoring in the low or moderate range of government restrictions on religion, on average, from 2018 through 2022. They include three countries classified by the EIU in 2022 as “full democracies” (Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom) and three classified as “flawed democracies” (Belgium, Brazil and the Philippines). Eight additional countries in this group were classified as authoritarian regimes and four as hybrid regimes.5

Nine of the 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa fall within these categories (countries with high SHI and low GRI scores) on our indexes, as do five of the 45 countries in Europe, two of the 35 countries in the Americas, one of the 50 Asia-Pacific countries, and two of the 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region.

Restrictions on religion in 2022

Government restrictions

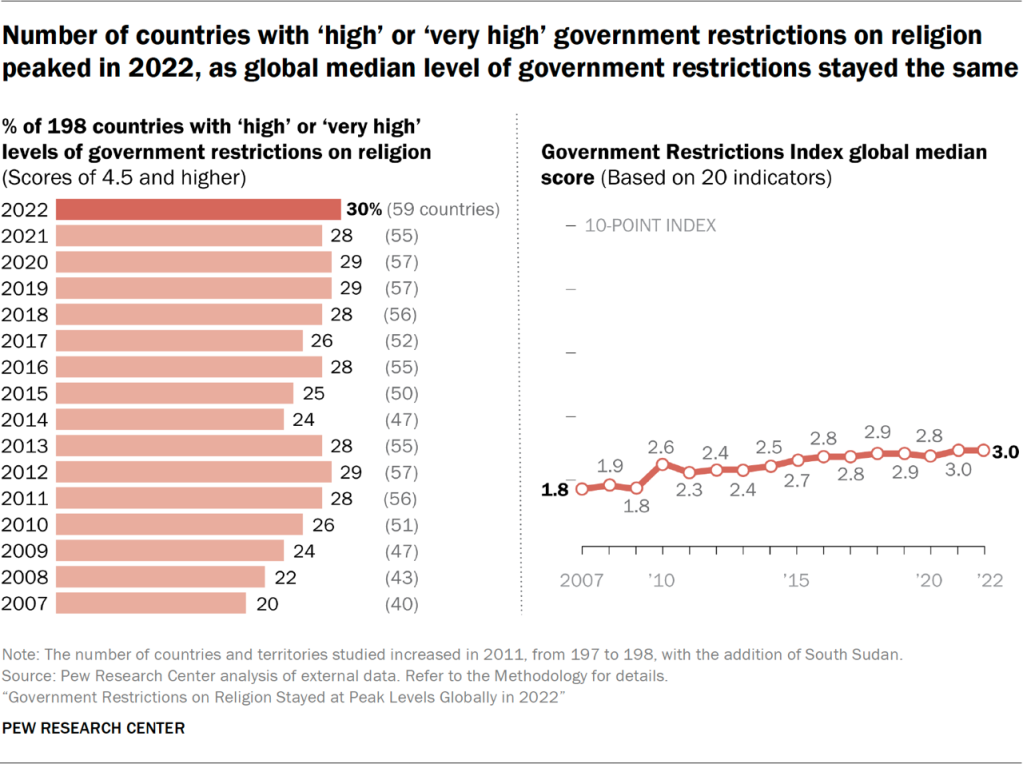

While the global median score on the Government Restrictions Index held steady in 2022 at 3.0 out of a possible 10.0, the number of countries with high or very high levels of government restrictions on religion rose to 59 (30% of all 198 countries and territories studied), up from 55 in 2021. This was the highest number since the study began in 2007. Still, most countries around the world (139, or 70%) had low or moderate levels of government restrictions on religion in 2022.

Government restrictions have gradually risen globally since 2007, when the median score on the GRI among all 197 countries and territories was 1.8. In 2021 and 2022, the median GRI score for all 198 countries and territories studied was 3.0.

Social hostilities

In 2022 the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index remained at 1.6 – the same as in 2021. At the same time, the number of countries with high or very high levels of social hostilities increased slightly to 45 (or 23% of all studied), up from 43 countries the previous year. Most countries (153, or 77%) had low or moderate levels of social hostilities involving religion in 2022.

Social hostilities include incidents that tend to vary more widely from year to year than laws and government policies do. The worldwide median score on the SHI started at 1.0 in 2007, reached a peak of 2.1 in 2017, and fell to 1.6 in 2021, where it remained in 2022.

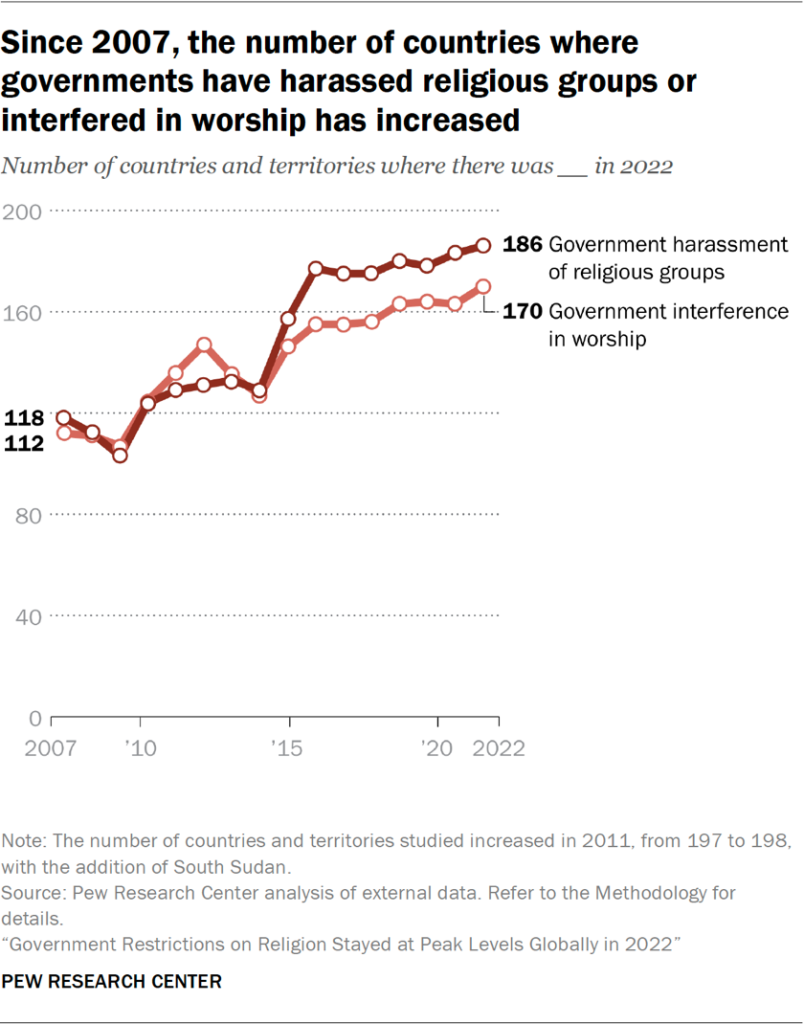

Government harassment of religious groups and interference in worship in 2022

Harassment by governments – a broad measure that captures both verbal and physical pressure by authorities on religious groups – was one of the most prevalent types of restrictions we measured in 2022. It was reported in 186 of the 198 countries and territories in the study (94%).

Government interference in worship also remained common around the world in 2022. It was reported by the sources used in this study in 170 countries and territories (86%). We define “government interference” to include policies and actions that disrupt religious activities, such as withholding permission to worship or denying access to places of worship. The term “interference” also covers restrictions on religious practices and rituals not specifically tied to worship, such as burial practices or conscientious objections to military service.

Figures on both government harassment and interference in worship were at peak levels for the study in 2022.

For more information on government harassment, go to Chapter 2.