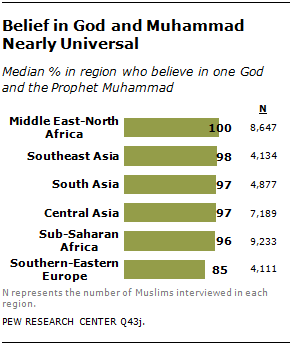

The world’s 1.6 billion Muslims are united in their belief in God and the Prophet Muhammad and are bound together by such religious practices as fasting during the holy month of Ramadan and almsgiving to assist people in need. But they have widely differing views about many other aspects of their faith, including how important religion is to their lives, who counts as a Muslim and what practices are acceptable in Islam, according to a worldwide survey by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life.

The survey, which involved more than 38,000 face-to-face interviews in over 80 languages, finds that in addition to the widespread conviction that there is only one God and that Muhammad is His Prophet, large percentages of Muslims around the world share other articles of faith, including belief in angels, heaven, hell and fate (or predestination). While there is broad agreement on the core tenets of Islam, however, Muslims across the 39 countries and territories surveyed differ significantly in their levels of religious commitment, openness to multiple interpretations of their faith and acceptance of various sects and movements.

Some of these differences are apparent at a regional level. For example, at least eight-in-ten Muslims in every country surveyed in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and South Asia say that religion is very important in their lives. Across the Middle East and North Africa, roughly six-in-ten or more say the same. And in the United States, a 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that nearly seven-in-ten Muslims (69%) say religion is very important to them. (For more comparisons with U.S. Muslims, see Appendix A.) But religion plays a much less central role for some Muslims, particularly in nations that only recently have emerged from communism. No more than half of those surveyed in Russia, the Balkans and the former Soviet republics of Central Asia say religion is very important in their lives. The one exception across this broad swath of Eastern Europe, Southern Europe and Central Asia is Turkey, which never came under communist rule; fully two-thirds of Turkish Muslims (67%) say religion is very important to them.

Generational differences are also apparent. Across the Middle East and North Africa, for example, Muslims 35 and older tend to place greater emphasis on religion and to exhibit higher levels of religious commitment than do Muslims between the ages of 18 and 34. In all seven countries surveyed in the region, older Muslims are more likely to report that they attend mosque, read the Quran (also spelled Koran) on a daily basis and pray multiple times each day. Outside of the Middle East and North Africa, the generational differences are not as sharp. And the survey finds that in one country – Russia – the general pattern is reversed and younger Muslims are significantly more observant than their elders.

There are also differences in how male and female Muslims practice their faith. In most of the 39 countries surveyed, men are more likely than women to attend mosque. This is especially true in Central Asia and South Asia, where majorities of women in most of the countries surveyed say they never attend mosque. However, this disparity appears to result from cultural norms or local customs that constrain women from attending mosque, rather than from differences in the importance that Muslim women and men place on religion. In most countries surveyed, for example, women are about as likely as men to read (or listen to readings from) the Quran on a daily basis. And there are no consistent differences between men and women when it comes to the frequency of prayer or participation in annual rites, such as almsgiving and fasting during Ramadan.

Sectarian Differences

The survey asked Muslims whether they identify with various branches of Islam and about their attitudes toward other branches or subgroups. While these sectarian differences are important in some countries, the survey suggests that many Muslims around the world either do not know or do not care about them.

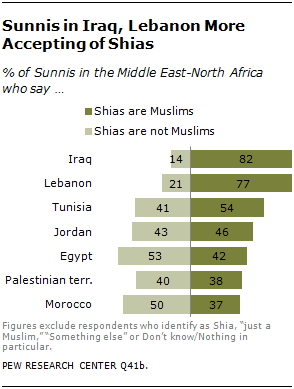

Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa tend to be most keenly aware of the distinction between the two main branches of Islam, Sunni and Shia.2 (See text box for definitions.) In most countries surveyed in the region, at least 40% of Sunnis do not accept Shias as fellow Muslims. In many cases, even greater percentages do not believe that some practices common among Shias, such as visiting the shrines of saints, are acceptable as part of Islamic tradition. Only in Lebanon and Iraq – nations where sizable populations of Sunnis and Shias live side by side – do large majorities of Sunnis recognize Shias as fellow Muslims and accept their distinctive practices as part of Islam.

Outside of the Middle East and North Africa, the distinction between Sunni and Shia appears to be of lesser consequence. In many of the countries surveyed in Central Asia, for instance, most Muslims do not identify with either branch of Islam, saying instead that they are “just a Muslim.” A similar pattern prevails in Southern and Eastern Europe, where pluralities or majorities in all countries identify as “just a Muslim.” In some of these countries, decades of communist rule may have made sectarian distinctions unfamiliar. But identification as “just a Muslim” is also prevalent in many countries without a communist legacy. For example, in Indonesia, which has the world’s largest Muslim population, 26% of Muslims describe themselves as Sunnis, compared with 56% who say they are “just a Muslim” and 13% who do not give a definite response.

Opinion also varies as to whether Sufis – members of religious orders who emphasize the mystical dimensions of Islam – belong to the Islamic faith.3 In South Asia, Sufis are widely seen as Muslims, while in other regions they tend to be less well known or not widely accepted as part of the Islamic tradition. Views differ, too, with regard to certain practices traditionally associated with particular Sufi orders. For example, reciting poetry or singing in praise of God is generally accepted in most of the countries where the question was asked. But only in Turkey do a majority of Muslims believe that devotional dancing is an acceptable form of worship, likely reflecting the historical prominence of the Mevlevi or “whirling dervish” Sufi order in Turkey.

Differing Views on Orthodoxy

The survey asked Muslims whether they believe there is only one true way to understand Islam’s teachings or if multiple interpretations are possible. In 32 of the 39 countries surveyed, half or more Muslims say there is only one correct way to understand the teachings of Islam.

This view, however, is far from universal. In the Middle East and North Africa, majorities or substantial minorities in most countries – including Tunisia, Morocco, the Palestinian territories, Lebanon and Iraq – believe that it is possible to interpret Islam’s teachings in multiple ways. In sub-Saharan Africa, at least one-in-five Muslims agree. In South Asia, Southeast Asia and across Southern and Eastern Europe, at least one-in-six in every country surveyed believe Islam is open to multiple interpretations.

In some Central Asian countries, slightly fewer Muslims say their faith can be subject to more than one interpretation. But in Kazakhstan (31%), Turkey (22%) and Kyrgyzstan (17%), the percentage that holds this view is on par with countries in other regions.

In the United States, by contrast, 57% of Muslims say Islam is open to multiple interpretations. On this measure, Muslim Americans look similar to Muslims in Morocco and Tunisia. (For more comparisons with previous surveys of U.S. Muslims, see Appendix A.)

What is a Median?

The median is the middle number in a list of numbers sorted from highest to lowest. On many questions in this report, medians are reported for groups of countries to help readers see regional patterns in religious beliefs and practices.

For a region with an odd number of countries, the median on a particular question is the middle spot among the countries surveyed in that region. For regions with an even number of countries, the median is computed as the average of the two countries at the middle of the list (e.g., where six nations are shown, the median is the average of the third and fourth countries listed in the region).

By contrast, figures reported for individual countries represent the total percentage for the category reported.

Core Beliefs

Traditionally, Muslims adhere to several articles of faith. Among the most widely known are: there is only one God; God has sent numerous messengers, with Muhammad being His final Prophet; God has revealed Holy Scriptures, including the Quran; God’s angels exist, even if people cannot see them; there will be a Day of Judgment, when God will determine whether individuals are consigned to heaven or hell; and God’s will and knowledge are absolute, meaning that people are subject to fate or predestination.4

As previously noted, belief in one God and the Prophet Muhammad is nearly universal among Muslims in most countries surveyed. Although the survey asked only respondents in sub-Saharan Africa whether they consider the Quran to be the word of God, the findings in that region indicate broad assent.5 Across most of the African nations surveyed, more than nine-in-ten Muslims say the Quran is the word of God, and solid majorities say it should be taken literally, word for word. Only in two countries in the region – Guinea Bissau (59%) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (54%) – do smaller percentages think the Quran should be read literally. The results in those two countries are similar to the United States, where 86% of Muslims said in a 2007 survey that the Quran was the word of God, including 50% who said it should be read literally, word for word. (For more U.S. results, see Appendix A.)

The survey asked respondents in all 39 countries whether they believe in the existence of angels. In Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East-North Africa region, belief in angels is nearly universal. In Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa more than seven-in-ten also say angels are real. Even in Southern and Eastern Europe, a median of 55% share this view.

The expression “Inshallah” (“If God wills”) is a common figure of speech among Muslims and reflects the Islamic tradition that the destiny of individuals, and the world, is in the hands of God. And indeed, the survey finds that the concept of predestination, or fate, is widely accepted among Muslims in most parts of the world. In four of the five regions where the question was asked, medians of about nine-in-ten (88% to 93%) say they believe in fate, while a median of 57% express this view in Southern and Eastern Europe.

The survey also asked about the existence of heaven and hell. Across the six regions included in the study, a median of more than seven-in-ten Muslims say that paradise awaits those who have lived righteous lives, while a median of at least two-thirds say hell is the ultimate fate of those who do not live righteously and do not repent.

Unifying Rituals

Along with the core beliefs discussed above, Islam is defined by “Five Pillars” – basic rituals that are obligatory for all members of the Islamic community who are physically able to perform them. The Five Pillars include: the profession of faith (shahadah); daily prayer (salat); fasting during the holy month of Ramadan (sawm); annual almsgiving to assist the poor or needy (zakat); and participation in the annual pilgrimage to Mecca at least once during one’s lifetime (hajj). Two of these – fasting during Ramadan and almsgiving – stand out as communal rituals that are especially widespread among Muslims across the globe.

Fasting during the month of Ramadan, which according to Islamic tradition is required of all healthy, adult Muslims, is part of an annual rite in which individuals place renewed emphasis on the teachings of the Quran. The survey finds that many Muslims in all six major geographical regions surveyed observe the month-long, daytime fast during Ramadan. In Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa, medians of more than nine-in-ten say they fast annually (94%-99%). Many Muslims in Southern and Eastern Europe and in Central Asia also report fasting during Ramadan.

Annual almsgiving, which by custom is supposed to equal approximately 2.5% of a person’s total wealth, is almost as widely observed as fasting during Ramadan. In Southeast Asia and South Asia, a median of roughly nine-in-ten Muslims (93% and 89%, respectively) say they perform zakat. At least three-quarters of respondents in the countries surveyed in the Middle East and North Africa (79%) and sub-Saharan Africa (77%) also report that they perform zakat. Smaller majorities in Central Asia (69%) and Southern and Eastern Europe (56%) say they practice annual almsgiving.

One Faith, Different Levels of Commitment

These common practices and shared beliefs help to explain why, to many Muslims, the principles of Islam seem both clear and universal. As mentioned above, half or more in most of the 39 countries surveyed agree that there is only one way to interpret the teachings of Islam.

But even though the idea of a single faith is widespread, the survey finds that Muslims differ significantly in their assessments of the importance of religion in their lives, as well as in their views about the forms of worship that should be accepted as part of the Islamic faith.

Central Asia along with Southern and Eastern Europe have relatively low levels of religious commitment, both in terms of the lower importance that Muslims in those regions place on religion and in terms of self-reported religious practices. With the exception of Turkey, where two-thirds of Muslims say religion is very important in their lives, half or fewer across these two regions say religion is personally very important to them. This includes Kazakhstan and Albania, where just 18% and 15%, respectively, say religion is central to their lives. (See “How Much Religion Matters” chart.)

Along with the lower percentages who say religion is very important in their lives, Muslims in Central Asia and across Southern and Eastern Europe also report lower levels of religious practice than Muslims in other regions. For instance, only in Azerbaijan does a majority (70%) pray more than once a day. Elsewhere in these two regions, the number of Muslims who say they pray several times a day ranges from slightly more than four-in-ten in Kosovo (43%), Turkey (43%) and Tajikistan (42%) to fewer than one-in-ten in Albania (7%) and Kazakhstan (4%).

In other regions included in the study, daily prayer is much more common among Muslims. In Southeast Asia, for example, at least three-quarters pray more than once a day, while in the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, majorities in most countries report the same.

Muslims in Central Asia, as well as in Southern and Eastern Europe, also tend to be less observant than their counterparts in other regions when it comes to mosque attendance. Just over four-in-ten Turkish Muslims (44%) say they visit their local mosque once a week or more, while three-in-ten do the same in Tajikistan and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In the remaining countries, fewer than a quarter of Muslims say they go to worship services at least once a week.

By contrast, outside Central Asia and the Southern-Eastern Europe region, substantially larger percentages of Muslims say they attend mosque once a week or more, although only in sub-Saharan Africa do broad majorities in all countries display this high level of religious commitment.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that despite lower levels of religious commitment on some measures, majorities of Muslims across most of Central Asia and Southern and Eastern Europe nonetheless subscribe to core tenets of Islam, and many also report that they observe such pillars of the faith as fasting during Ramadan and annual almsgiving to the poor.

Generational Differences in Religious Commitment

Of all the countries surveyed, only in Russia do Muslims ages 18-34 place significantly more importance on religion than Muslims 35 and older (48% vs. 41%). Younger Muslims in Russia also tend to pray more frequently (48% do so once a day or more, compared with 41% of older Muslims).

Elsewhere in Southern and Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the older generation of Muslims generally places a greater emphasis on religion and engages more often in prayer. For example, Muslims ages 35 and older are more likely than younger Muslims to pray several times a day in Uzbekistan (+18 percentage points), Tajikistan (+16) and Kyrgyzstan (+8).

The biggest generational differences are found in the Middle East and North Africa. In Lebanon, for example, Muslims ages 35 and older are 28 percentage points more likely than younger Muslims to pray several times a day, 20 points more likely to attend mosque at least weekly and 18 points more likely to read the Quran daily. On each of these measures, age gaps of 10 points or more also are found in the Palestinian territories, Morocco and Tunisia. And somewhat smaller but statistically significant differences are observed as well in Jordan and Egypt.

Women and Men Similar, Except in Mosque Attendance

Across the six regions included in the survey, women and men tend to be very similar in terms of the role religion plays in daily life. This holds true for the importance that both sexes place on religion, as well as for the frequency with which they observe daily rituals, such as prayer and reading (or listening to) the Quran. For example, among the countries surveyed in Central Asia, a median of 43% of Muslim women say religion is very important in their lives, compared with 42% of men. When it comes to prayer, medians of 31% of women and 28% of men in Central Asia pray several times a day. And nearly equal percentages of women (8%) and men (6%) across the region say they read or listen to the Quran daily.

The one exception to this pattern is mosque attendance: women are much more likely than men to say they never visit their local mosque. This gender gap is largest in South Asia and Central Asia. In South Asia, including Pakistan, a median of about three-quarters of women (77%) say they never attend mosque, compared with just 1% of men. In Central Asia, the comparable figures are 74% and 20%. Gender differences in mosque attendance are smaller, though still significant, in Southern and Eastern Europe (+27 percentage points) and the Middle East-North Africa region (+26 points). There is little or no gap, however, in Southeast Asia (+4) and sub-Saharan Africa (+1).

Sectarian Differences Vary in Importance

The survey finds that sectarian identities, especially the distinction between Sunni and Shia Muslims, seem to be unfamiliar or unimportant to many Muslims. This is especially true across Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as in Central Asia, where medians of at least 50% describe themselves as “just a Muslim” rather than as a follower of any particular branch of Islam. Substantial minorities in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia also identify as “just a Muslim” (regional medians of 23% and 18%).

Sectarian identities appear to be particularly relevant in South Asia and the Middle East-North Africa region, where majorities identify as Sunnis or Shias. In the Middle East and North Africa, moreover, widespread identification with the Sunni sect is often coupled with mixed views about whether Shias are Muslims.

In five of seven countries surveyed in the Middle East and North Africa, at least four-in-ten or more Sunnis say Shias are not Muslims.6 Only in Iraq and Lebanon do overwhelming majorities of Sunnis accept Shias as members of the same faith. Indeed, Sunnis in these two countries are at least 23 to 28 percentage points more likely than Sunnis elsewhere in the region to recognize Shias as Muslims.7

This greater willingness of Sunnis in Iraq and Lebanon to accept Shias as fellow Muslims extends as well to attitudes about forms of worship traditionally associated with Shias. For example, while most Sunnis in the Middle East and North Africa view pilgrimages to the shrines of saints as falling outside Islamic tradition, majorities of Sunnis in Lebanon (98%) and Iraq (65%) believe this practice is acceptable in Islam. In this regard, Sunnis in these two countries resemble their fellow Shia countrymen more than they resemble Sunnis in neighboring countries such as Egypt and Jordan.

In Lebanon sectarian attitudes vary significantly by age. Lebanese Sunnis who are 35 and older are less willing than younger Sunnis to accept Shias as Muslims. The history of sectarian conflict in Lebanon in the 1970s and 1980s may help explain the generational difference. Sunnis who came of age during the conflict years are less inclined to view Shias as fellow Muslims. Yet, even with this generational difference, both younger and older Sunnis in Lebanon still are more willing than most Sunnis in the Middle East-North Africa region to say that Shias share the same faith.

Not just in the Middle East and North Africa but in other regions as well, the willingness of Sunnis to accept Shia as fellow Muslims tends to be higher in countries with sizable Shia populations. For example, in Azerbaijan, Afghanistan and Russia – countries with self-identified Shia populations ranging from 6% to 37% – clear majorities of Sunnis (both men and women, young and old) agree that Shias belong to the Islamic faith. On the other hand, in Pakistan, where 6% of the survey respondents identify as Shia, Sunni attitudes are more mixed: 50% say Shias are Muslims, while 41% say they are not.

Sunni Muslims and Shia Muslims (also known as Shiites) comprise the two main branches of Islam. Sunni and Shia identities first formed soon after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 C.E., centering on a dispute over leadership succession. Over time, however, the political divide between the two groups broadened to include theological distinctions and differences in religious practices as well.

While the two groups are similar in many ways, they differ over conceptions of religious authority and interpretation as well as the role of the Prophet Muhammad’s descendants, among other issues.

Members of Sufi orders, which embrace mystical practices, can fall within either the Sunni or the Shia tradition. In some cases, Sufis may accept teachings from both traditions.

For additional information regarding Sunni and Shia Islam, see John Esposito, editor. 2003. “Shii Islam” and “Sunni Islam” in “The Oxford Dictionary of Islam.” Oxford: Oxford University Press, pages 290-93 and 304-307.

Views of Other Groups

The survey also asked about attitudes toward Sufis and members of regionally specific groups or movements. Views of Sufis vary greatly by region. In South Asia, for example, a median of 77% consider Sufis to be Muslims; half in the Middle East and North Africa concur. However, significantly fewer Muslims in other regions surveyed accept Sufis as members of the Islamic faith. For example, in Southern and Eastern Europe (Russia and the Balkans), a median of 32% recognize Sufis as fellow Muslims, while in Southeast Asia and Central Asia the comparable figures are 24% and 18%.

Especially in Central Asia, the low percentage that accepts Sufis as Muslims may be linked to a lack of knowledge about this mystical branch of Islam: majorities in most Central Asian countries surveyed say either that they have never heard of Sufis or that they do not have an opinion about whether Sufis are Muslims.

Views of regionally or locally based groups and movements are mixed. For example, in South Asia and Southeast Asia, relatively few Muslims accept Ahmadiyyas as members of the Islamic faith. Only in Bangladesh do as many as four-in-ten recognize members of this movement as fellow Muslims; elsewhere in the two regions, a quarter or fewer agree. Even smaller percentages in Malaysia and Indonesia (9% and 5%, respectively) say that members of the mystical Aliran Kepercayaan movement are Muslims. (See Glossary for brief definitions of these groups.)

In Turkey, most Muslims (69%) acknowledge Alevis, who are part of the Shia tradition, as fellow Muslims. Meanwhile, in Lebanon, a modest majority (57%) say members of the Alawite sect are Muslims. By comparison, only about four-in-ten Lebanese Muslims (39%) say the same about the Druze.

About the Report

These and other findings are discussed in more detail in the remainder of this report, which is divided into six main sections:

- Religious Affiliation

- Religious Commitment

- Articles of Faith

- Other Beliefs and Practices

- Boundaries of Religious Identity

- Boundaries of Religious Practice

This report also includes an appendix with comparable results from past Pew Research Center surveys of Muslims in the United States. There is also a glossary of key terms. The survey questionnaire and a topline with full results is also available. The report also includes an infographic. This report covers religious affiliation, beliefs and practices. A second report will cover Muslims’ attitudes and views on a variety of social and political questions.

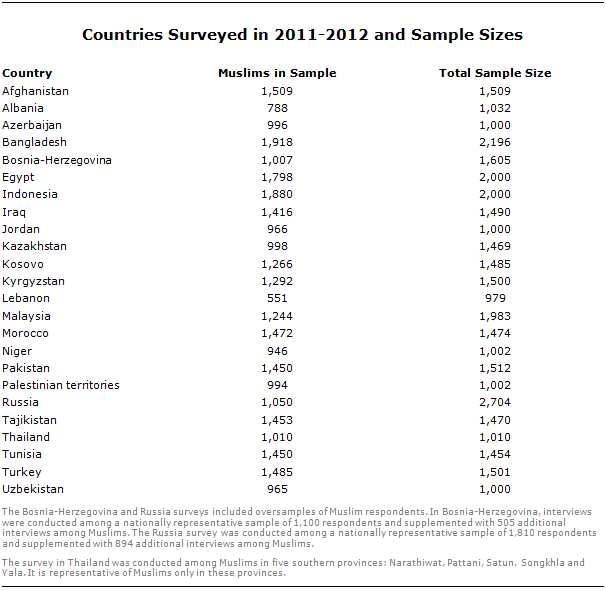

The Pew Forum’s survey of the world’s Muslims includes every nation with a Muslim population of more than 10 million except Algeria, China, India, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. Together, the 39 countries and territories included in the survey are home to about two-thirds of all Muslims in the world.

The surveys that are the basis for this report were conducted across multiple years. Fifteen sub-Saharan countries with substantial Muslim populations were surveyed in 2008-2009 as part of a larger project that examined religion in that region. The methods employed in those countries – as well as some of the findings – are detailed in the Pew Forum report “Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa.” An additional 24 countries and territories were surveyed in 2011-2012. In 21 of these countries, Muslims make up a majority of the population. In these cases, nationally representative samples of at least 1,000 respondents were fielded. The number of self-identified Muslims interviewed in these countries ranged from 551 in Lebanon to 1,918 in Bangladesh. In Russia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where Muslims are a minority, oversamples were employed to ensure adequate representation of Muslims; in both cases, at least 1,000 Muslims were interviewed. Meanwhile, in Thailand, the survey was limited to the country’s five southern provinces, each with substantial Muslim populations; more than 1,000 interviews with Muslims were conducted across these provinces. Appendix C provides greater detail on the 2011-2012 survey’s methodology.

Footnotes:

2 According to Pew Forum estimates, 87-90% of the world’s Muslims are Sunnis, while 10-13% are Shias. For country-by-country estimates of the percentage of Sunnis and Shias, see the Pew Forum’s 2009 report “Mapping the Global Muslim Population,” page 38. (return to text)

3 For background on Sufi orders, see the Pew Forum’s 2010 report “Muslim Networks and Movements in Western Europe.” (return to text)

4 Enumerations and translations of the articles of faith vary. Most are derived from the Hadith of Gabriel. See, for example, Sahih al-Bukhari 2:47 and Sahih al-Muslim 1:1. For details on hadith, see text box in Chapter 3. (return to text)

5 In 2008-2009, the Pew Forum asked both Muslims and Christians in sub-Saharan Africa if the sacred texts of their respective religions are the word of God and should be taken literally. The results are reported in the 2010 report “Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa.” (return to text)

6 Questions about views of Muslim sects were not asked in sub-Saharan Africa. (return to text)

7 All figures for Shia and Sunni subgroups within countries are based on self-identification in response to a multi-part survey question that first asked if an individual was Muslim (Q28 and Q28b), and if yes, if they were Sunni, Shia or “something else” (Q31). The percentage of Shias and Sunnis identified by the survey may diverge from country estimates reported in the Pew Forum’s 2009 report “Mapping the Global Muslim Population,” which are based on demographic and ethnographic analyses, as well as reviews of frequently used estimates. (return to text)

Photo Credit: © SZE FEI WONG / istockphoto