Roughly a quarter of a century after the fall of the Iron Curtain and subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, a major new Pew Research Center survey finds that religion has reasserted itself as an important part of individual and national identity in many of the Central and Eastern European countries where communist regimes once repressed religious worship and promoted atheism.

Roughly a quarter of a century after the fall of the Iron Curtain and subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, a major new Pew Research Center survey finds that religion has reasserted itself as an important part of individual and national identity in many of the Central and Eastern European countries where communist regimes once repressed religious worship and promoted atheism.

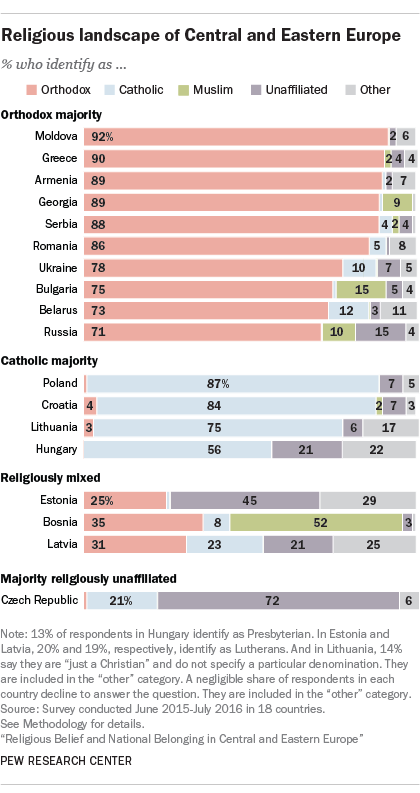

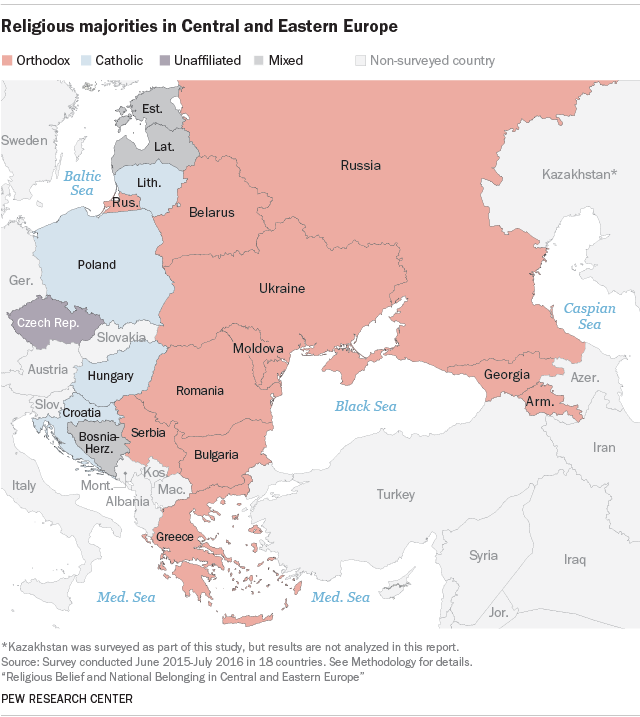

Today, solid majorities of adults across much of the region say they believe in God, and most identify with a religion. Orthodox Christianity and Roman Catholicism are the most prevalent religious affiliations, much as they were more than 100 years ago in the twilight years of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires.

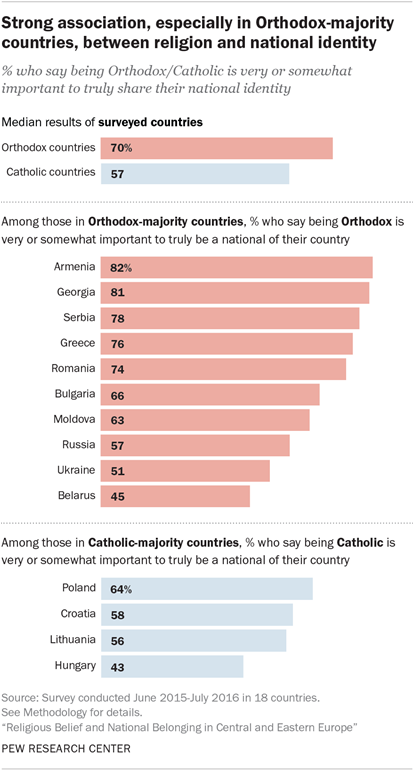

In many Central and Eastern European countries, religion and national identity are closely entwined. This is true in former communist states, such as the Russian Federation and Poland, where majorities say that being Orthodox or Catholic is important to being “truly Russian” or “truly Polish.” It is also the case in Greece, where the church played a central role in Greece’s successful struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire and where today three-quarters of the public (76%) says that being Orthodox is important to being “truly Greek.”

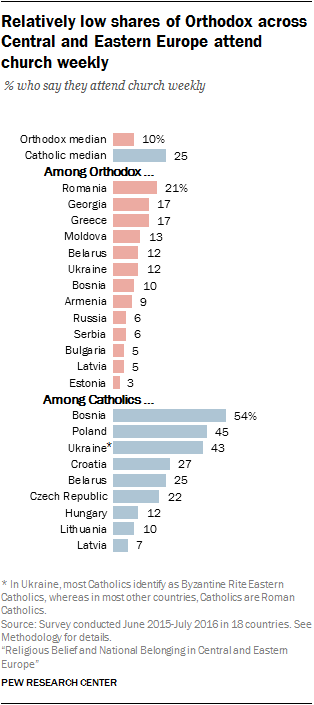

Many people in the region embrace religion as an element of national belonging even though they are not highly observant. Relatively few Orthodox or Catholic adults in Central and Eastern Europe say they regularly attend worship services, pray often or consider religion central to their lives. For example, a median of just 10% of Orthodox Christians across the region say they go to church on a weekly basis.

Indeed, compared with many populations Pew Research Center previously has surveyed – from the United States to Latin America to sub-Saharan Africa to Muslims in the Middle East and North Africa – Central and Eastern Europeans display relatively low levels of religious observance.

Around the world, different ways of being religious

Believing. Behaving. Belonging.

Three words, three distinct ways in which people connect (or don’t) to religion: Do they believe in a higher power? Do they pray and perform rituals? Do they feel part of a congregation, spiritual community or religious group?

Research suggests that many people around the world engage with religion in at least one of these ways, but not necessarily all three.

Christians in Western Europe, for example, have been described as “believing without belonging,” a phrase coined by sociologist Grace Davie in her 1994 religious profile of Great Britain, where, she noted, widespread belief in God coexists with largely empty churches and low participation in religious institutions.1

In East Asia, there is a different paradigm, one that might be called “behaving without believing or belonging.” According to a major ethnography conducted last decade, for example, many people in China neither believe in a higher power nor identify with any particular religious faith, yet nevertheless go to Buddhist or Confucian temples to make offerings and partake in religious rituals.2

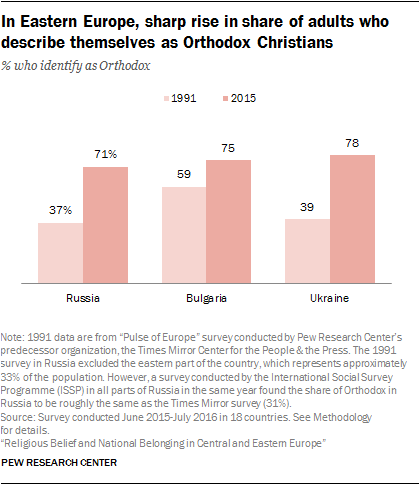

Nonetheless, the comeback of religion in a region once dominated by atheist regimes is striking – particularly in some historically Orthodox countries, where levels of religious affiliation have risen substantially in recent decades.

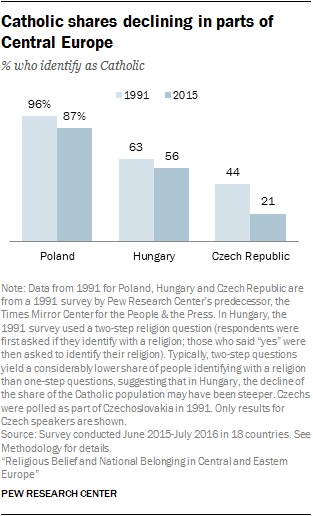

Catholicism in Central and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, has not experienced the same upsurge as Orthodox Christianity. In part, this may be because much of the population in countries such as Poland and Hungary retained a Catholic identity during the communist era, leaving less of a religious vacuum to be filled when the USSR fell.

Catholicism in Central and Eastern Europe, meanwhile, has not experienced the same upsurge as Orthodox Christianity. In part, this may be because much of the population in countries such as Poland and Hungary retained a Catholic identity during the communist era, leaving less of a religious vacuum to be filled when the USSR fell.

To the extent that there has been measurable religious change in recent decades in Central and Eastern European countries with large Catholic populations, it has been in the direction of greater secularization. The most dramatic shift in this regard has occurred in the Czech Republic, where the share of the public identifying as Catholic dropped from 44% in 1991 to 21% in the current survey. Today, the Czech Republic is one of the most secular countries in Europe, with nearly three-quarters of adults (72%) describing their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.”

To the extent that there has been measurable religious change in recent decades in Central and Eastern European countries with large Catholic populations, it has been in the direction of greater secularization. The most dramatic shift in this regard has occurred in the Czech Republic, where the share of the public identifying as Catholic dropped from 44% in 1991 to 21% in the current survey. Today, the Czech Republic is one of the most secular countries in Europe, with nearly three-quarters of adults (72%) describing their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.”

The differing trends in predominantly Orthodox and Catholic countries may be, at least in part, a reflection of political geography. The Orthodox countries in the region are further toward the east, and many were part of the Soviet Union. The Catholic countries are further toward the west, and only Lithuania was part of the USSR.

The differing trends in predominantly Orthodox and Catholic countries may be, at least in part, a reflection of political geography. The Orthodox countries in the region are further toward the east, and many were part of the Soviet Union. The Catholic countries are further toward the west, and only Lithuania was part of the USSR.

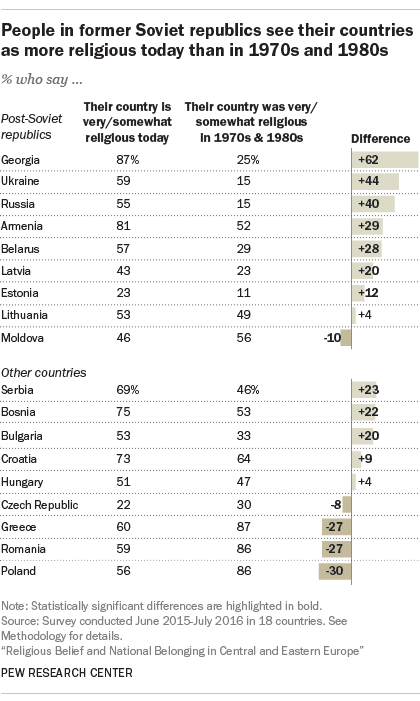

This political divide is seen in responses to two separate survey questions: How religious do you think your country was in the 1970s and 1980s (when all but Greece among the surveyed countries were ruled by communist regimes), and how religious is it today? With few exceptions, in former Soviet republics the more common view is that those countries are more religious now than a few decades ago. Only 15% of Russians, for example, say their country was either “very religious” (3%) or “somewhat religious” (12%) in the 1970s and 1980s, while 55% say Russia is either very (8%) or somewhat (47%) religious today.

There is more variation in the answers to these questions in countries that were beyond the borders of the former USSR. In contrast with most of the former Soviet republics, respondents in Poland, Romania and Greece say their countries have become considerably less religious in recent decades.

But these perceptions do not tell the entire story. Despite declining shares in some countries, Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe generally are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, at least by conventional measures. For instance, 45% of Catholics in Poland say they attend worship services at least weekly – more than double the share of Orthodox Christians in any country surveyed who say they go to church that often.

But these perceptions do not tell the entire story. Despite declining shares in some countries, Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe generally are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, at least by conventional measures. For instance, 45% of Catholics in Poland say they attend worship services at least weekly – more than double the share of Orthodox Christians in any country surveyed who say they go to church that often.

In addition, Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe are much more likely than Orthodox Christians to say they engage in religious practices such as taking communion and fasting during Lent. Catholics also are somewhat more likely than Orthodox Christians to say they frequently share their views on God with others, and to say they read or listen to scripture outside of religious services.5

Although Catholics overall are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, however, the association between religious identity and national identity is stronger in Orthodox-majority countries than in Catholic ones.

Although Catholics overall are more religiously observant than Orthodox Christians in the region, however, the association between religious identity and national identity is stronger in Orthodox-majority countries than in Catholic ones.

Across the countries where Orthodox Christians make up a majority, a median of 70% say it is important to be Orthodox to truly share the national identity of their country (e.g., that one must be Russian Orthodox to be “truly Russian,” or Greek Orthodox to be “truly Greek”). By comparison, a median of 57% in the four Catholic-majority countries say this about being Catholic. (Fewer people in Western Europe – for example, 23% in France and 30% in Germany – say being Christian is very or somewhat important to their national identity.)

These nationalist sentiments are especially common among members of the majority religious group in each country. But, in some cases, even members of religious minority groups take this position. For example, about a quarter of both Muslims and religiously unaffiliated people in Russia say it is important to be Russian Orthodox in order to be “truly Russian.”

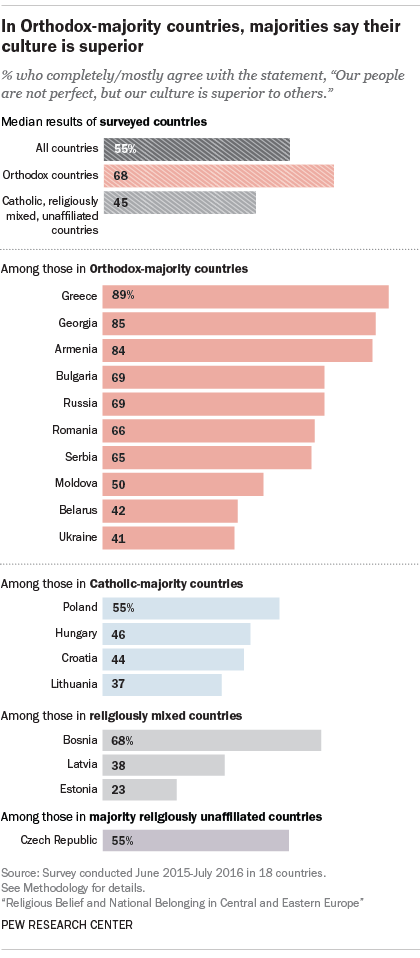

In addition, people living in predominantly Orthodox countries are more inclined than others in the region to say their culture “is superior to others” and to describe themselves as “very proud” of their national identity.

In addition, people living in predominantly Orthodox countries are more inclined than others in the region to say their culture “is superior to others” and to describe themselves as “very proud” of their national identity.

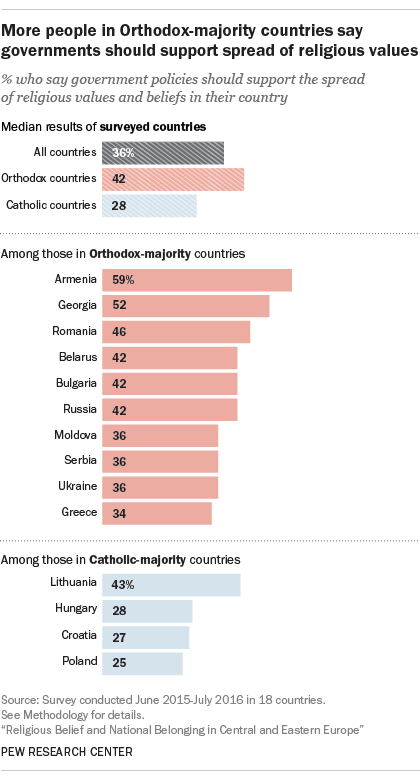

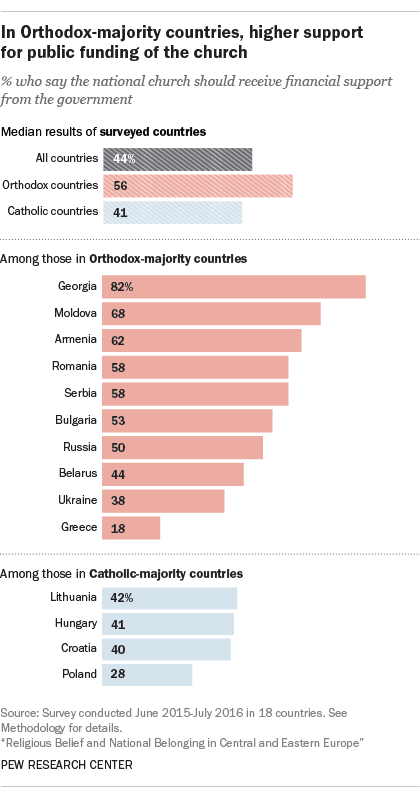

Many of the predominantly Orthodox countries surveyed have centuries-old national churches, such as the Greek Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox Church and Armenian Apostolic Church, and there is popular support for these institutions to play a large role in public life.6 Across all the Orthodox-majority countries surveyed, a median of 56% favor state funding for their national churches. And a median of 42% say their governments should promote religious values and beliefs. In Catholic-majority countries, there is greater support for separation of religion from the state, with a median of just 41% who back state funding of churches and 28% in favor of governments promoting religious values and beliefs.

The political – and sometimes religious – map of Central and Eastern Europe has been redrawn numerous times over the centuries. Russia, whether as a synonym for the czarist empire or the USSR, has played a pivotal role in defining the political and cultural boundaries of the region.

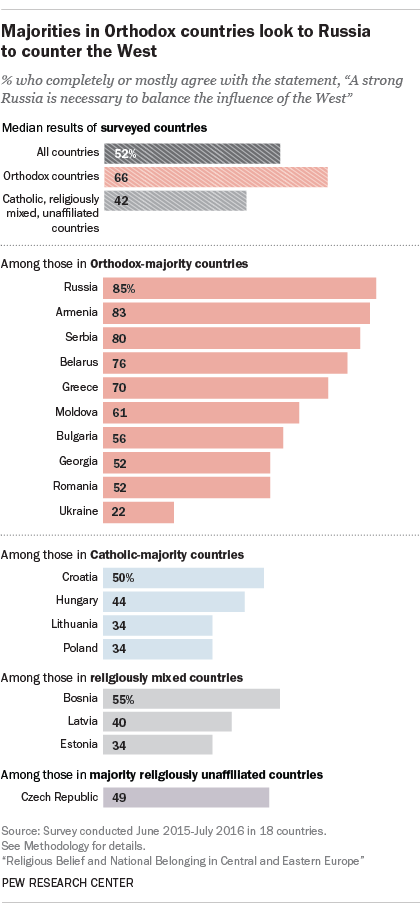

Today, many Orthodox Christians – and not only Russian Orthodox Christians – express pro-Russia views. Most see Russia as an important buffer against the influence of the West, and many say Russia has a special obligation to protect not only ethnic Russians, but also Orthodox Christians in other countries.7 In Catholic-majority and religiously mixed countries across the region, there is much less public support for a strong Russia as a counterweight to the West and a protector of either ethnic Russians or Orthodox Christians outside Russia’s borders.

Today, many Orthodox Christians – and not only Russian Orthodox Christians – express pro-Russia views. Most see Russia as an important buffer against the influence of the West, and many say Russia has a special obligation to protect not only ethnic Russians, but also Orthodox Christians in other countries.7 In Catholic-majority and religiously mixed countries across the region, there is much less public support for a strong Russia as a counterweight to the West and a protector of either ethnic Russians or Orthodox Christians outside Russia’s borders.

In many ways, then, the return of religion since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union has played out differently in the predominantly Orthodox countries of Eastern Europe than it has among the heavily Catholic or mixed-religious populations further to the West. In the Orthodox countries, there has been an upsurge of religious identity, but levels of religious practice are comparatively low. And Orthodox identity is tightly bound up with national identity, feelings of pride and cultural superiority, support for linkages between national churches and governments, and views of Russia as a bulwark against the West.

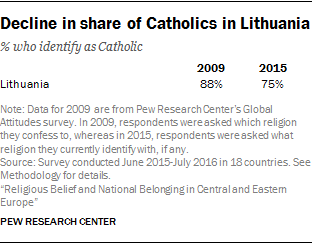

Meanwhile, in such historically Catholic countries as Poland, Hungary, Lithuania and the Czech Republic, there has not been a marked rise in religious identification since the fall of the USSR; on the contrary, the share of adults in these countries who identify as Catholic has declined. But levels of church attendance and other measures of religious observance in the region’s Catholic-majority countries are generally higher than in their Orthodox neighbors (although still low in comparison with many other parts of the world). The link between religious identity and national identity is present across the region but somewhat weaker in the Catholic-majority countries. And politically, the Catholic countries tend to look West rather than East: Far more people in Poland, Hungary, Lithuania and Croatia say it is in their country’s interest to work closely with the U.S. and other Western powers than take the position that a strong Russia is necessary to balance the West.

What is a median?

On some questions throughout this report, median percentages are reported to help readers see overall patterns. The median is the middle number in a list of figures sorted in ascending or descending order. In a survey of 18 countries, the median result is the average of the ninth and 10th on a list of country-level findings ranked in order.

In addition to looking at medians based on all of the survey’s respondents across 18 countries, this report sometimes refers to the median among a specific subset of respondents and/or countries. For example, in 13 countries, the number of Orthodox Christians surveyed is large enough to be analyzed and broken out separately. The regional median for Orthodox Christians is the seventh-highest result when the findings solely among Orthodox respondents in those 13 countries are listed from highest to lowest.

These are among the key findings of the Pew Research Center survey, which was conducted from June 2015 to July 2016 through face-to-face interviews in 17 languages with more than 25,000 adults ages 18 and older in 18 countries. The study, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America and the Caribbean; Israel; and the United States.

While there is no consensus over the exact boundaries of Central and Eastern Europe, the new survey spans a vast area running eastward from the Czech Republic and Poland to Russia, Georgia and Armenia, and southward from the Baltic States to the Balkans and Greece. (See related map.) Over the centuries, nationhood, politics and religion have converged and diverged in the region as empires have risen and crumbled and independence has been lost and regained.

Most of the countries surveyed were once ruled by communist regimes, either aligned or not aligned with Moscow. But Greece remained outside the Iron Curtain and became allied with Western Europe after World War II. In this respect, Greece offers a useful point of comparison with other Orthodox-majority countries in the region. It is both of the West and of the East. For example, Greeks report relatively low levels of religious practice, while expressing strong feelings of cultural superiority and national pride – similar to respondents in other Orthodox-majority countries surveyed. But Greeks also differ: For instance, they are more supportive of democracy and less socially conservative than neighbors in majority-Orthodox countries.

Central and Eastern Europe includes a few Muslim-majority countries. Pew Research Center previously surveyed them as part of a study of Muslims around the world. For more on these countries, see the related sidebar.

The survey does not include several Christian-majority countries in Central and Eastern Europe: Macedonia, Montenegro and Cyprus, which have Orthodox majorities, and Slovakia and Slovenia, which are predominantly Catholic.

In addition to asking questions about religious identity, beliefs and practices and national identity, the survey probed respondents’ views on social issues, democracy, the economy, religious and ethnic pluralism and more.

Orthodox Christians make up majority in the region

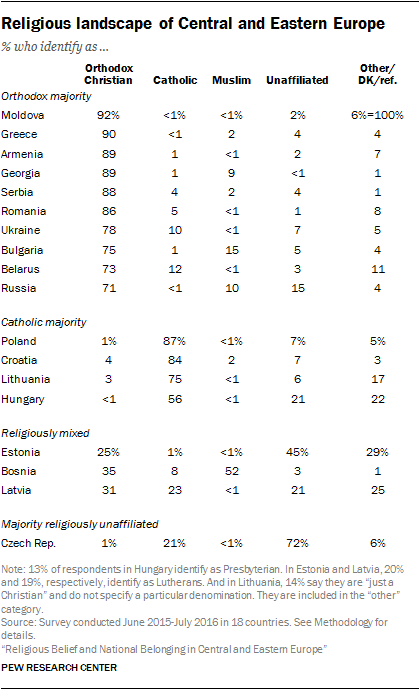

Overall, an estimated 57% of people living in the region surveyed identify as Orthodox. 8 This includes large majorities in 10 countries, including Russia, Ukraine, Greece, Romania and several others. Orthodox Christians also form significant minorities in Bosnia (35%), Latvia (31%) and Estonia (25%).

Overall, an estimated 57% of people living in the region surveyed identify as Orthodox. 8 This includes large majorities in 10 countries, including Russia, Ukraine, Greece, Romania and several others. Orthodox Christians also form significant minorities in Bosnia (35%), Latvia (31%) and Estonia (25%).

Catholics make up about 18% of the region’s population, including majorities of adults in Poland, Croatia, Lithuania and Hungary.

The next largest group, at 14% of the region’s population, is the religiously unaffiliated – people who identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” The religiously unaffiliated make up a solid majority (72%) of adults in the Czech Republic and a plurality (45%) in Estonia.

Protestants are a smaller presence in the region, though in some countries they are sizable minorities. In Estonia and Latvia, for example, roughly one-in-five adults identify as Lutheran. And 13% of Hungarians identify with the Presbyterian/Reformed Church.

What other surveys have shown about religion in Central and Eastern Europe

Since the early 1990s, several survey organizations have sought to measure religious affiliation in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, among them the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), New Russia Barometer, New Europe Barometer, New Baltic Barometer and the Center for the Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. Some of these polls also have asked about belief in God and frequency of church attendance.

Since the early 1990s, several survey organizations have sought to measure religious affiliation in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, among them the International Social Survey Program (ISSP), New Russia Barometer, New Europe Barometer, New Baltic Barometer and the Center for the Study of Public Policy at the University of Strathclyde. Some of these polls also have asked about belief in God and frequency of church attendance.

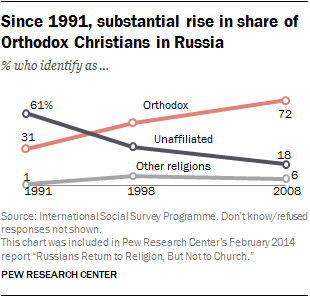

While most of these surveys cover Russia, data showing trends over time in other Orthodox countries since the 1990s are scarce. And because of major differences in question wording, as well as widely differing methodological approaches to sampling minority populations, the surveys arrive at varying estimates of the size of different religious groups, including Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Muslims and people with no religious affiliation.9 On the whole, though, they point to a sharp revival of religious identity in Russia beginning in the early 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union. For example, ISSP surveys conducted in Russia in 1991, 1998 and 2008 show the share of Orthodox Christians more than doubling from 31% to 72%, while at the same time, the share of religiously unaffiliated adults declined from a majority in 1991 (61%) to 18% in 2008.

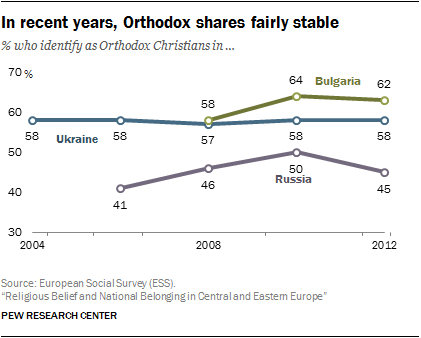

Some of the more recent surveys suggest that this Orthodox revival has slowed or leveled off in the last decade or so. For example, European Social Survey (ESS) polls show a relatively stable share of Orthodox Christians in Russia, Bulgaria and Ukraine since about 2006, as illustrated in the accompanying chart, and Pew Research Center polls show a similar trend.

At the same time, surveys indicate that the shares of adults engaging in religious practices have remained largely stable since the fall of the Soviet Union. In Russia, according to New Russia Barometer surveys, approximately as many religiously affiliated adults said they attended church monthly in 2007 (12%) as in 1993 (11%).

At the same time, surveys indicate that the shares of adults engaging in religious practices have remained largely stable since the fall of the Soviet Union. In Russia, according to New Russia Barometer surveys, approximately as many religiously affiliated adults said they attended church monthly in 2007 (12%) as in 1993 (11%).

In Catholic-majority countries, church attendance rates may even have declined, according to some surveys. For instance, in New Baltic Barometer surveys conducted in Lithuania, 25% of adults said they attended church at least once a month in 2004, down from 35% in 1993.

Few people attend church, but most believe in God

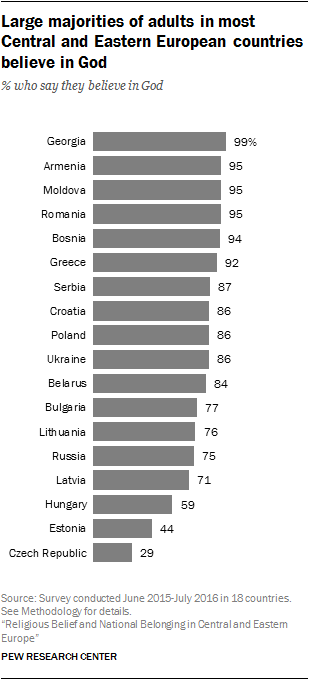

Even though relatively few people in many countries across Central and Eastern Europe say they attend church weekly, a median of 86% across the 18 countries surveyed say they believe in God. This includes more than nine-in-ten in Georgia (99%), Armenia (95%), Moldova (95%), Romania (95%) and Bosnia (94%). The Czech Republic and Estonia are the two biggest exceptions to this pattern; in both places, fewer than half (29% and 44%, respectively) say they believe in God.

Even though relatively few people in many countries across Central and Eastern Europe say they attend church weekly, a median of 86% across the 18 countries surveyed say they believe in God. This includes more than nine-in-ten in Georgia (99%), Armenia (95%), Moldova (95%), Romania (95%) and Bosnia (94%). The Czech Republic and Estonia are the two biggest exceptions to this pattern; in both places, fewer than half (29% and 44%, respectively) say they believe in God.

Overall, people in Central and Eastern Europe are somewhat less likely to say they believe in God than adults previously surveyed in Africa and Latin America, among whom belief is almost universal. Still, across this region – with its unique history of state-supported atheism and separation of religion from public life – it is striking that the vast majority of adults express belief in God.

Lower percentages across Central and Eastern Europe – though still majorities in about half the countries – believe in heaven (median of 59%) and hell (median of 54%). Across the countries surveyed, Catholics tend to express higher levels of belief in heaven and hell than do Orthodox Christians.

Belief in fate (i.e., that the course of one’s life is largely or wholly preordained) and the existence of the soul also are fairly common – at least half of adults express these beliefs in nearly every country surveyed. Even among people who do not identify with a religion, substantial shares say they believe in fate and the soul. In the Czech Republic, where just three-in-ten people (29%) say they believe in God, higher shares express belief in fate (43%) and the existence of the soul (44%).

Religion in the Czech Republic, Central and Eastern Europe’s most secular country

The Czech Republic stands out in this report as the only country surveyed where most adults are religiously unaffiliated. When asked about their religion, 72% of Czech respondents identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” and roughly two-thirds (66%) say they do not believe in God. Given that other countries in Central and Eastern Europe emerged from communist rule with much higher levels of religious affiliation, this raises the question: Why aren’t Czechs more religious?

For clues, scholars have looked to the past, identifying a pattern of Czech distaste for the pressures emanating from religious and secular authorities. This goes back as far as 1415, when followers of Jan Hus, a priest in Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), separated from the Roman Catholic Church after Hus was burned at the stake for heresy.

Throughout the 15th century, in a precursor of sorts to the Protestant Reformation, these so-called “Hussites” gained enough influence that the vast majority of the Czech population no longer identified as Catholic.10 But after the Thirty Years’ War (1618 to 1648), this break from Catholicism reversed itself when the Catholic Austro-Hungarian Empire fiercely repressed the Hussites and other Protestants and forcibly re-Catholicized the area. While the region would become overwhelmingly Catholic, historians argue that the repression of this period reverberates to the present day in the collective Czech memory, casting the Catholic Church as an overly privileged partner of foreign occupiers.

Anticlericalism surged in the years of Czech independence after World War I, with the country’s Catholic population declining by an estimated 1.5 million people, half of whom did not join another denomination.11 After World War II, the Soviet-influenced regime, which was officially atheist, furthered this disaffiliation.

Openness to religion briefly spiked after the fall of communism, though evidence suggests this may have been mostly a political statement against the communist regime, and since the early 1990s, the share of Czechs who say they have a religious affiliation has declined.12

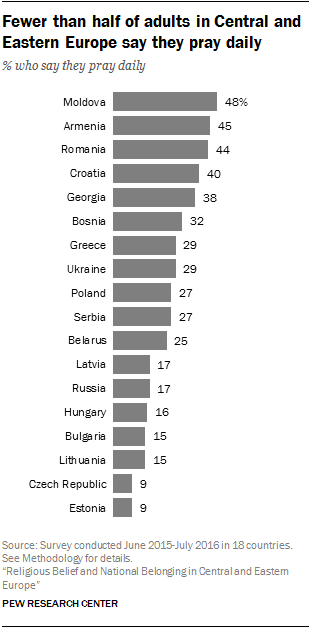

Relatively few people in the region pray daily

Despite the high levels of belief in God throughout most of the region, daily prayer is not the norm in Central and Eastern Europe. For instance, just 17% of Russians and 27% of both Poles and Serbians say they pray at least once a day. By comparison, more than half of U.S. adults (55%) say they pray every day.

Despite the high levels of belief in God throughout most of the region, daily prayer is not the norm in Central and Eastern Europe. For instance, just 17% of Russians and 27% of both Poles and Serbians say they pray at least once a day. By comparison, more than half of U.S. adults (55%) say they pray every day.

People in the region are much more likely to take part in other religious practices, such as having icons or other holy figures in their homes or wearing religious symbols (such as a cross). And very high shares of both Catholics and Orthodox Christians in virtually every country surveyed say they have been baptized.

For more on religious practices, see Chapter 2.

Conservative views on sexuality and gender

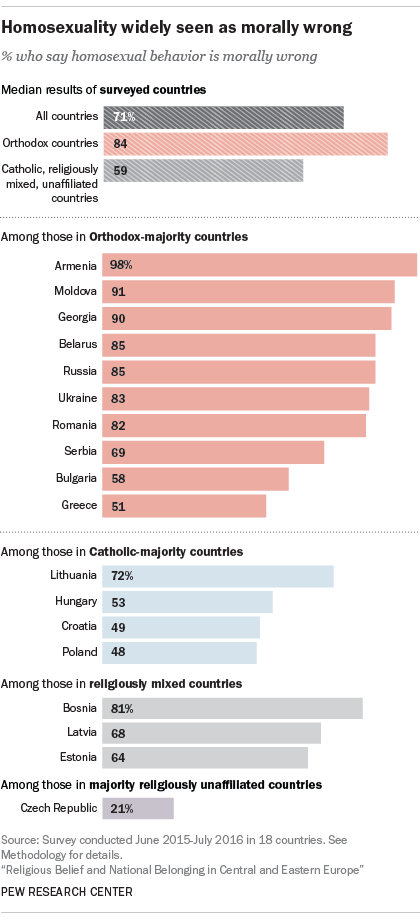

Opposition to homosexuality throughout the region

In the U.S. and many other countries, people who are more religious generally have more conservative views on social issues such as homosexuality and abortion. While this pattern is also seen within individual countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the most religious countries in the region (by conventional measures such as overall rates of church attendance) are not necessarily the most socially conservative.

In the U.S. and many other countries, people who are more religious generally have more conservative views on social issues such as homosexuality and abortion. While this pattern is also seen within individual countries in Central and Eastern Europe, the most religious countries in the region (by conventional measures such as overall rates of church attendance) are not necessarily the most socially conservative.

For example, although levels of church attendance and prayer are relatively low in Orthodox-majority Russia, 85% of Russians overall say homosexual behavior is morally wrong. Even among religiously unaffiliated Russians, three-quarters say homosexuality is morally wrong and 79% say society should not accept it.

By contrast, in Catholic-majority Poland, where the population as a whole is more religiously observant, only about half of adults (48%) say homosexuality is morally wrong. Roughly four-in-ten Catholic Poles (41%) say society should accept homosexuality.

This pattern, in which Orthodox countries are more socially conservative even though they may be less religious, is seen throughout the region.

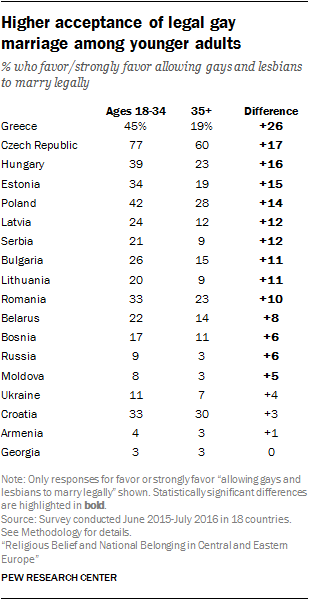

Young adults somewhat more liberal on homosexuality, same-sex marriage

Across the region, younger people (that is, adults under 35) are less opposed to homosexuality and more inclined than their elders to favor legal gay marriage.

Across the region, younger people (that is, adults under 35) are less opposed to homosexuality and more inclined than their elders to favor legal gay marriage.

But even among younger people, the prevailing view is that homosexuality is morally wrong, and relatively few young adults (except in the Czech Republic) favor gay marriage. In some countries, there is little or no difference between the views of younger and older adults on these issues. For example, in Ukraine, younger people are about as likely as their elders to favor legal gay marriage (11% vs. 7%).

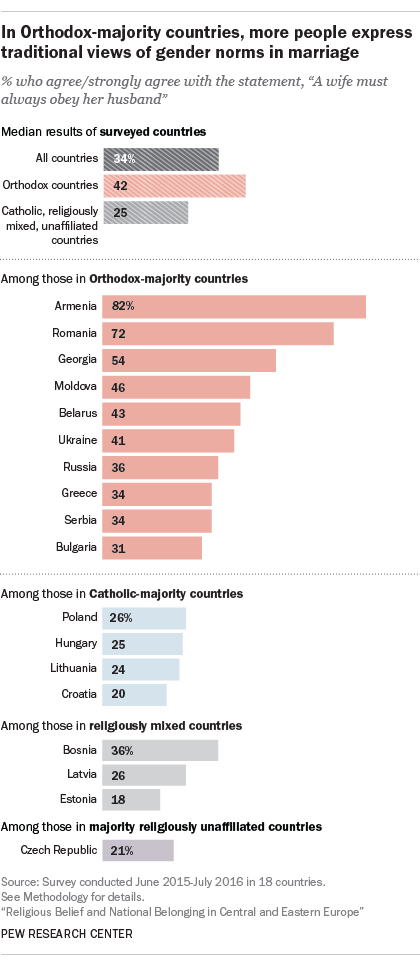

Many in Orthodox countries associate women with traditional roles

People in Orthodox-majority countries are more likely than those elsewhere in the region to hold traditional views of gender roles – such as women having a social responsibility to bear children and wives being obligated to obey their husbands.

People in Orthodox-majority countries are more likely than those elsewhere in the region to hold traditional views of gender roles – such as women having a social responsibility to bear children and wives being obligated to obey their husbands.

Along these same lines, roughly four-in-ten or more adults in most Orthodox-majority countries say that when unemployment is high, men should have more rights to a job. In the eight non-Orthodox countries surveyed, the share that holds this view ranges from 19% in Estonia to 39% in Bosnia.

Russia’s regional influence

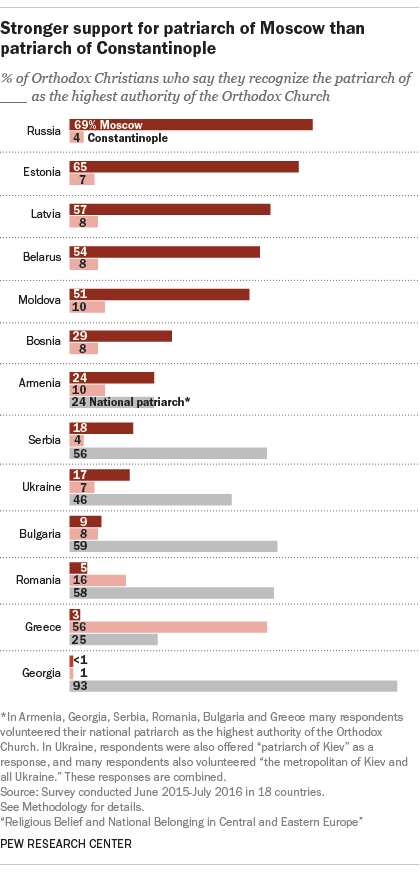

Many see Moscow patriarch as highest authority of Orthodoxy

Many Orthodox Christians across the region look toward Russian religious leadership. While there is no central authority in Orthodox Christianity akin to the pope in Catholicism, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople is often referred to as the “first among equals” (in Latin, “primus inter pares”) in his spiritual leadership of the Greek Orthodox and other Orthodox Christians around the world.13 But Greece is the only country surveyed where a majority of Orthodox Christians say they view the patriarch of Constantinople as the highest authority in Orthodoxy.

Many Orthodox Christians across the region look toward Russian religious leadership. While there is no central authority in Orthodox Christianity akin to the pope in Catholicism, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople is often referred to as the “first among equals” (in Latin, “primus inter pares”) in his spiritual leadership of the Greek Orthodox and other Orthodox Christians around the world.13 But Greece is the only country surveyed where a majority of Orthodox Christians say they view the patriarch of Constantinople as the highest authority in Orthodoxy.

Substantial shares of Orthodox Christians – even outside Russia – see the patriarch of Moscow (currently Kirill) as the highest authority in the Orthodox Church, including roughly half or more not only in Estonia and Latvia, where about three-in-four Orthodox Christians identify as ethnic Russians, but also in Belarus and Moldova, where the vast majority of Orthodox Christians are not ethnic Russians.

In countries such as Armenia, Serbia and Ukraine, many people regard the national patriarchs as the main religious authorities. But even in these three nations, roughly one-in-six or more Orthodox Christians say the patriarch of Moscow is the highest authority in Orthodoxy – despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of Orthodox Christians in these countries do not self-identify as ethnic Russians or with the Russian Orthodox Church.

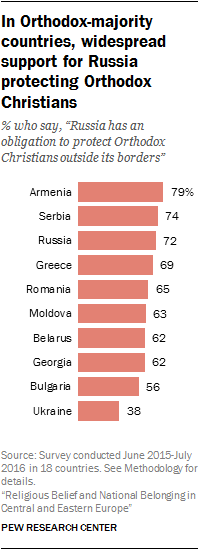

Should Russia protect Orthodox Christians outside its borders?

In addition to having the largest Orthodox Christian population in the world (more than 100 million), Russia plays central cultural and geopolitical roles in the region. In all but one Orthodox-majority country surveyed, most adults agree with the notion that Russia has an obligation to protect Orthodox Christians outside its borders.

In addition to having the largest Orthodox Christian population in the world (more than 100 million), Russia plays central cultural and geopolitical roles in the region. In all but one Orthodox-majority country surveyed, most adults agree with the notion that Russia has an obligation to protect Orthodox Christians outside its borders.

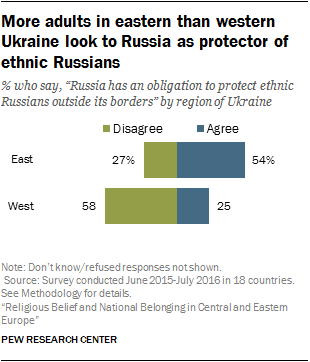

The lone exception is Ukraine, which lost effective control over Crimea to Russia in 2014 and is still engaged in a conflict with pro-Russian separatists in the eastern part of the country. Yet, even outside the territories in conflict, more than a third of Ukrainian adults (38%) say Russia has an obligation to protect Orthodox Christians in other countries. (For a more detailed explanation of ethnic and religious divides in Ukraine, see the sidebar later in this chapter.)

Russians generally accept this role; 72% of Russians agree that their country has an obligation to protect Orthodox Christians in other countries. But this sense of national responsibility or bond with Orthodox Christians outside Russia’s borders does not necessarily extend to a personal level. Just 44% of Orthodox Christians in Russia say they feel a strong bond with other Orthodox Christians around the world, and 54% say they personally feel a special responsibility to support other Orthodox Christians.

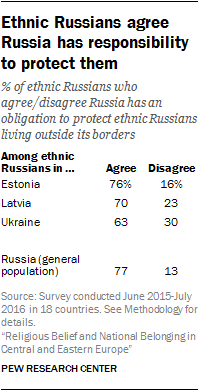

Ethnic Russians say Russia has an obligation to protect them

The survey also asked respondents whether Russia has an obligation to protect ethnic Russians living outside its borders. 14

The survey also asked respondents whether Russia has an obligation to protect ethnic Russians living outside its borders. 14

Several former Soviet republics have ethnic Russian minority populations. For example, 31% of adults surveyed in Latvia describe themselves as ethnically Russian, as do 25% in Estonia and 8% of those surveyed in Ukraine.15 Most ethnic Russians in these countries identify as Orthodox Christians. And in all three of these countries, clear majorities of ethnic Russians agree that Russia has a responsibility to protect them.

Russians generally accept this responsibility, with 77% agreeing that Russia has an obligation to protect ethnic Russians living in other countries.

In the other Orthodox-majority countries surveyed, no more than 6% of all respondents identify as ethnic Russians. But still, in some of these places, solid majorities agree Russia has an obligation to protect people of Russian ethnicity living outside its borders, including 86% in Serbia and 62% in Georgia. Once again, fewer Ukrainians (38%) agree with this view.

Ukraine divided between east and west

The survey results highlight an east-west divide within Ukraine. In the new survey, about seven-in-ten adults (69%) in western Ukraine say it is in their country’s interest to work closely with the United States and other Western powers, compared with 53% in eastern Ukraine. And adults in the western region are less likely than easterners to see a conflict between Ukraine’s “traditional values” and those of the West.

Eastern Ukrainians, meanwhile, are more likely to favor a strong Russia on the world stage. Eastern Ukrainians are more likely than Ukrainians in the western part of the country to agree that “a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West” (29% vs. 17%). And more than half of adults (54%) in eastern Ukraine say Russia has an obligation to protect ethnic Russians outside its borders, while just a quarter of adults in western Ukraine say this

The survey also finds significant religious differences between residents of the two parts of the country. For example, people living in western Ukraine are more likely than those in the east to attend church on a weekly basis, to say religion is very important in their lives and to believe in God. In addition, nearly all Catholics in Ukraine live in the western part of the country, and western Ukraine has a somewhat higher concentration of Orthodox Christians who identify with the Kiev patriarchate than does eastern Ukraine. Even accounting for these religious differences, statistical analysis of the survey results suggests that where Ukrainians live (east or west) is a strong determinant of their attitudes toward Russia and the West – stronger than their religious affiliation, ethnicity, age, gender or level of education.

A similar political divide was found by Pew Research Center in a 2015 poll in Ukraine, which revealed that 56% of Ukrainians living in the country’s western region blamed Russia for the violence in eastern Ukraine, compared with only 33% of those living in the east.

Because of the security situation in eastern Ukraine, both the 2015 poll and the current poll exclude the contested regions of Luhansk, Donetsk and Crimea. The surveys cover approximately 80% of Ukraine’s total population, allowing for an analysis of east-west differences.

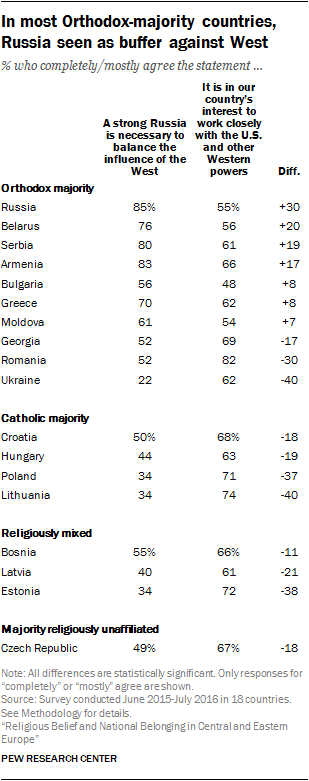

Most people across the region say it is in their country’s interest to work with the U.S. and the West

People in Orthodox-majority countries tend to see Russia as an important buffer against the West, with most in these nations (with the notable exception of Ukraine) saying that “a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West.” Even in Greece, a country that is part of the European Union, 70% agree a strong Russia is needed to balance the West.

People in Orthodox-majority countries tend to see Russia as an important buffer against the West, with most in these nations (with the notable exception of Ukraine) saying that “a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West.” Even in Greece, a country that is part of the European Union, 70% agree a strong Russia is needed to balance the West.

This sentiment is shared by considerably fewer people in Catholic and religiously mixed countries in the region.

At the same time, majorities in most countries surveyed – Orthodox and non-Orthodox – also say it is in their country’s interest to work closely with the U.S. and other Western powers.

People in Orthodox-majority countries tend to look more favorably toward Russian economic influence in the region. Larger shares of the public in Orthodox countries than elsewhere say Russian companies are having a good influence over the way things are going in their country. And across roughly half the Orthodox countries surveyed, smaller shares say American companies have a good influence within their borders than say the same about Russian companies. Only in two Orthodox countries (Ukraine and Romania) do more adults give positive assessments of American companies than of Russian ones.

In Estonia and Latvia, most self-identified ethnic Russians agree that a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West (71% and 64%, respectively). By contrast, among the rest of the populations in those countries, large shares hold the opposite point of view: In Estonia, 70% of respondents who identify with other ethnicities disagree that a strong Russia is needed to balance the influence of the West, as do 51% of Latvians belonging to other ethnicities. (Just 29% of Latvians who are not ethnic Russians agree a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West, while 20% do not take a clear position on the issue.) In Ukraine, ethnic Russians are about twice as likely as ethnic Ukrainians to say a strong Russia is necessary to counter the West, although ethnic Russians are closely divided on the issue (42% agree vs. 41% disagree).

Ukraine also is the only country surveyed where ethnic Russians are about equally likely to say American companies and Russian companies are having a good influence in their country. In Estonia and Latvia, ethnic Russians are far more likely to rate favorably the influence of Russian than American companies.

Culture clash with West

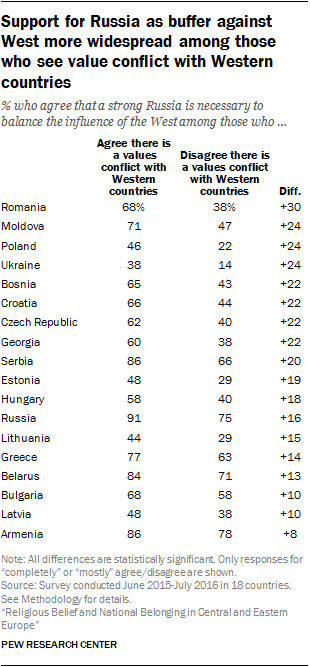

In part, the desire for a strong Russia may owe to a perceived values gap with the West. Across the region, people in Orthodox-majority countries are more likely than those in Catholic-majority countries to agree with the statement, “There is a conflict between our country’s traditional values and those of the West.” And respondents who agree with that statement also are more likely than those who disagree to say a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West.16

In part, the desire for a strong Russia may owe to a perceived values gap with the West. Across the region, people in Orthodox-majority countries are more likely than those in Catholic-majority countries to agree with the statement, “There is a conflict between our country’s traditional values and those of the West.” And respondents who agree with that statement also are more likely than those who disagree to say a strong Russia is necessary to balance the influence of the West.16

Many in former Soviet republics regret the Soviet Union’s demise

In former Soviet republics outside the Baltics, there is a robust strain of nostalgia for the USSR. In Moldova and Armenia, for example, majorities say the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 was bad for their country. Even in Ukraine, where an armed conflict with pro-Russian separatists continues, about one-third (34%) of the public feels this way.

In former Soviet republics outside the Baltics, there is a robust strain of nostalgia for the USSR. In Moldova and Armenia, for example, majorities say the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 was bad for their country. Even in Ukraine, where an armed conflict with pro-Russian separatists continues, about one-third (34%) of the public feels this way.

By contrast, in the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania the more widespread view is that the USSR’s dissolution was a good thing. (This question was asked only in countries that were once a part of the Soviet Union.)

In nearly every country, adults over the age of 5o (i.e., those who came of age during the Soviet era) are more likely than younger adults to say the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been a bad thing for their country. Ethnicity makes a difference as well: Ethnic Russians in Ukraine, Latvia and Estonia are more likely than people of other ethnicities in these countries to say the dissolution of the Soviet Union was a bad thing. In Latvia, for example, 53% of ethnic Russians say the dissolution of the Soviet Union was a bad thing, compared with 20% of all other Latvians.

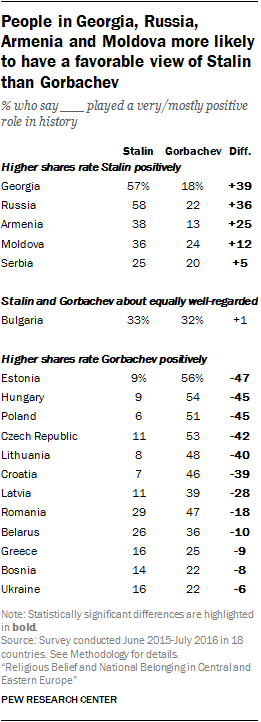

Nostalgia for the Soviet era also may be reflected in people’s views of two political leaders – Josef Stalin (who ruled from 1924 to 1953) and Mikhail Gorbachev (general secretary of the Communist Party from 1985 to 1991). Neither man is viewed positively across the region as a whole. But in several former Soviet republics, including Russia and his native Georgia, more people view Stalin favorably than view Gorbachev favorably. Meanwhile, Gorbachev receives more favorable ratings than Stalin does in the Baltic countries, as well as in Poland, Hungary, Croatia and the Czech Republic.

Nostalgia for the Soviet era also may be reflected in people’s views of two political leaders – Josef Stalin (who ruled from 1924 to 1953) and Mikhail Gorbachev (general secretary of the Communist Party from 1985 to 1991). Neither man is viewed positively across the region as a whole. But in several former Soviet republics, including Russia and his native Georgia, more people view Stalin favorably than view Gorbachev favorably. Meanwhile, Gorbachev receives more favorable ratings than Stalin does in the Baltic countries, as well as in Poland, Hungary, Croatia and the Czech Republic.

Many express doubts about democracy as best form of government

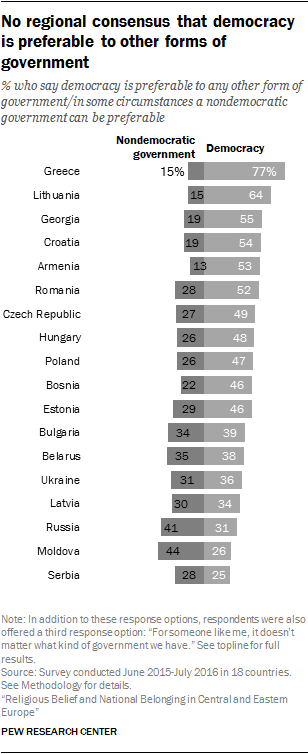

Following the fall of the Iron Curtain and collapse of the USSR, Western models of democratic government and market economies quickly spread across Central and Eastern Europe. Elsewhere, Pew Research Center has documented the wide range of public reactions to political and economic change between 1991 and 2009. Just as in that study, the new survey finds many people across the region harbor doubts about democracy.

Following the fall of the Iron Curtain and collapse of the USSR, Western models of democratic government and market economies quickly spread across Central and Eastern Europe. Elsewhere, Pew Research Center has documented the wide range of public reactions to political and economic change between 1991 and 2009. Just as in that study, the new survey finds many people across the region harbor doubts about democracy.

While the prevailing view in 11 of the 18 countries surveyed is that democracy is preferable to any other form of government, only in two countries – Greece (77%) and Lithuania (64%) – do clear majorities say this.

In many countries across Central and Eastern Europe, substantial shares of the public – including roughly one-third or more of adults in Bulgaria, Belarus, Russia and Moldova – take the position that under some circumstances, a nondemocratic government is preferable.

This survey question offered a third option as a response: “For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.” Considerable shares of respondents in many countries also take this position, including a plurality in Serbia (43%), about a third in Armenia (32%) and one-in-five Russians (20%).

In Orthodox countries, more people support a role for the church in public life

People in Orthodox-majority countries are more inclined than those elsewhere in the region to say their governments should support the spread of religious values and beliefs in the country and that governments should provide funding for their dominant, national churches.

People in Orthodox-majority countries are more inclined than those elsewhere in the region to say their governments should support the spread of religious values and beliefs in the country and that governments should provide funding for their dominant, national churches.

Roughly a third or more in Orthodox countries say their governments should support the spread of religious values and beliefs in their countries, including a majority in Armenia (59%) and roughly half in Georgia (52%). Support for government efforts to spread religious values is considerably lower in most Catholic countries – in Poland, Croatia and Hungary, majorities instead take the position that religion should be kept separate from government policies.

In addition, even though relatively few people in Orthodox-majority countries in the region say they personally attend church on a weekly basis, many more say their national Orthodox Church should receive government funding. In Russia, for example, 50% say the Russian Orthodox Church should receive government funding, even though just 7% of Russians say they attend services on a weekly basis. Similarly, 58% of Serbians say the Serbian Orthodox Church should receive funds from their government, while again, 7% say they go to religious services weekly.

In addition, even though relatively few people in Orthodox-majority countries in the region say they personally attend church on a weekly basis, many more say their national Orthodox Church should receive government funding. In Russia, for example, 50% say the Russian Orthodox Church should receive government funding, even though just 7% of Russians say they attend services on a weekly basis. Similarly, 58% of Serbians say the Serbian Orthodox Church should receive funds from their government, while again, 7% say they go to religious services weekly.

By comparison, 28% of Poles and about four-in-ten adults in Croatia, Lithuania and Hungary support government funding of the Catholic Church in these Catholic-majority countries.

Across several Orthodox- and Catholic-majority countries, people who do not identify with the predominant religion (whether Orthodoxy or Catholicism) are less likely than others to support the government spread of religious values as well as public funding for the church. For example, in Hungary, just 19% of religiously unaffiliated adults say the government should fund the Catholic Church, compared with about half of Catholics (51%).

But, in some cases, people in religious minority groups are nearly as likely as those in the majority to say the government should financially support the dominant church. In Russia, for instance, 50% of Muslims – compared to 56% of Orthodox Christians – say the Russian Orthodox Church should receive funding from the state.

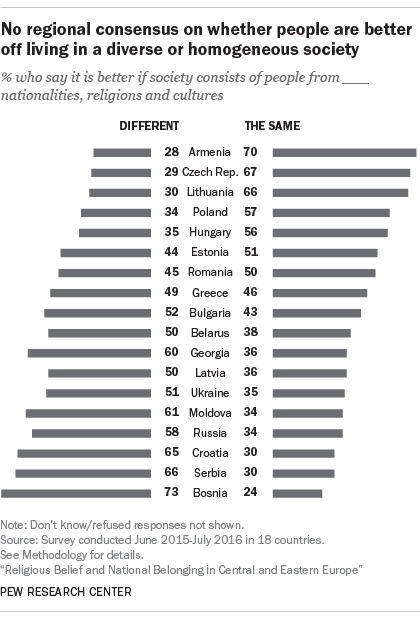

Views on diverse vs. homogeneous societies

Mixed opinions on whether a diverse or homogeneous society is better

The survey also probed views on religious and ethnic diversity. Respondents were asked to choose between two statements: “It is better for us if society consists of people from different nationalities, religions and cultures” or “It is better for us if society consists of people from the same nationality, and who have the same religion and culture.”

The survey also probed views on religious and ethnic diversity. Respondents were asked to choose between two statements: “It is better for us if society consists of people from different nationalities, religions and cultures” or “It is better for us if society consists of people from the same nationality, and who have the same religion and culture.”

Answers vary significantly across the region, with large majorities in countries that were part of the former Yugoslavia (Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia), which went through ethnic and religious wars in the 1990s, saying that a multicultural society is preferable.

Muslims tend to be more likely than Orthodox Christians and Catholics in the region to favor a multicultural society.

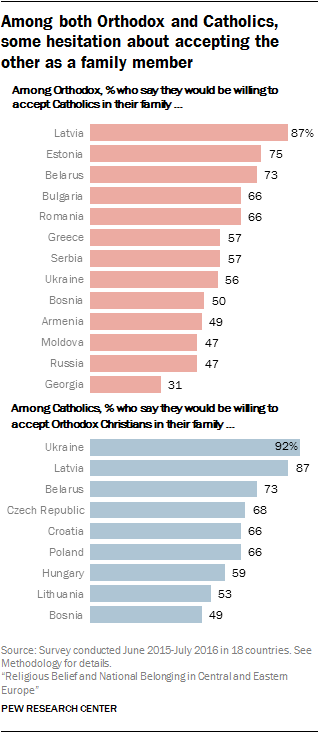

Varying levels of acceptance among Catholics, Orthodox and other groups

In addition to measuring broad attitudes toward diversity and pluralism, the survey also explored opinions about a number of specific religious and ethnic groups in the region. For example, how do the two largest religious groups in the region – Orthodox Christians and Catholics – view each other?

To begin with, many members of both Christian traditions say that Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy have a lot in common. But the Orthodox-Catholic schism is nearly 1,000 years old (it is conventionally dated to 1054, following a period of growing estrangement between the Eastern patriarchates and the Latin Church of Rome). And some modern Orthodox leaders have condemned the idea of reuniting with the Roman Catholic Church, expressing fears that liberal Western values would supplant traditional Orthodox ones.

Today, few Orthodox Christians in the region say the two churches should be in communion again, including as few as 17% in Russia and 19% in Georgia who favor reuniting with the Catholic Church.

In countries that have significant Catholic and Orthodox populations, Catholics are, on balance, more likely to favor communion between the two churches. In Ukraine, for example, about three-quarters (74%) of Catholics favor reunification of Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, a view held by only about one-third (34%) of the country’s Orthodox population. (See the related sidebar for an explanation of Ukraine’s religious and ethnic divides.)

In some cases, the estrangement between the two Christian traditions runs deeper. The survey asked Orthodox Christians and Catholics whether they would be willing to accept each other as fellow citizens of their country, as neighbors or as family members. In most countries, the vast majority of both groups say they would accept each other as citizens and as neighbors. But the survey reveals at least some hesitation on the part of both Orthodox Christians and Catholics to accept the other as family members, with Catholics somewhat more accepting of Orthodox Christians than vice versa. In Ukraine, where Catholics are a minority, there is a particularly large gap on this issue – 92% of Catholics say they would accept Orthodox Christians as family members, while far fewer Orthodox Christians (56%) in Ukraine say they would accept Catholics into their family.

In some cases, the estrangement between the two Christian traditions runs deeper. The survey asked Orthodox Christians and Catholics whether they would be willing to accept each other as fellow citizens of their country, as neighbors or as family members. In most countries, the vast majority of both groups say they would accept each other as citizens and as neighbors. But the survey reveals at least some hesitation on the part of both Orthodox Christians and Catholics to accept the other as family members, with Catholics somewhat more accepting of Orthodox Christians than vice versa. In Ukraine, where Catholics are a minority, there is a particularly large gap on this issue – 92% of Catholics say they would accept Orthodox Christians as family members, while far fewer Orthodox Christians (56%) in Ukraine say they would accept Catholics into their family.

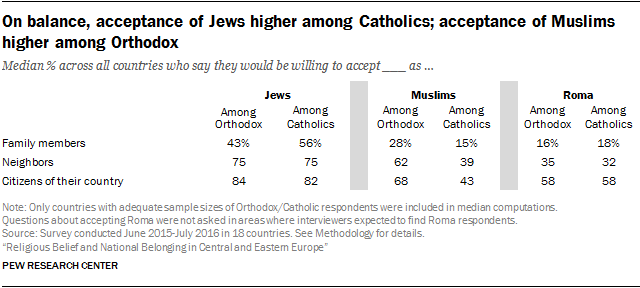

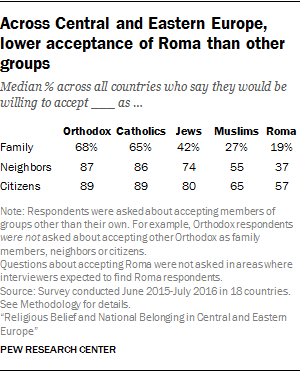

The survey also posed similar questions about three other religious or ethnic groups. Respondents were asked whether they would be willing to accept Jews, Muslims and Roma as citizens of their country, neighbors and family. The results of this battery of “social distance” questions suggest that there is less acceptance, in general, of these minorities in Central and Eastern Europe.

The survey also posed similar questions about three other religious or ethnic groups. Respondents were asked whether they would be willing to accept Jews, Muslims and Roma as citizens of their country, neighbors and family. The results of this battery of “social distance” questions suggest that there is less acceptance, in general, of these minorities in Central and Eastern Europe.

Roma (also known as Romani or Gypsies, a term some consider pejorative) face the lowest overall levels of acceptance. Across all 18 countries surveyed, a median of 57% of respondents say they would be willing to accept Roma as fellow citizens. Even lower shares say they would be willing to accept Roma as neighbors (a median of 37%) or family members (median of 19%). There is little or no difference between Catholics and Orthodox Christians when it comes to views of Roma.

On balance, acceptance of Jews is higher than of Muslims. But there are some differences in the attitudes of the major Christian groups toward these minorities. Overall, Catholics appear more willing than Orthodox Christians to accept Jews as family members.

On the other hand, Orthodox Christians are generally more inclined than Catholics across the region to accept Muslims as fellow citizens and neighbors. This may reflect, at least in part, the sizable Muslim populations in some countries that also have large Orthodox populations. Orthodox-majority Russia has approximately 14 million Muslims, the largest Muslim population in the region (in total number), and Bosnia has substantial populations of both Muslims and Orthodox Christians, but fewer Catholics.

People in Georgia and Armenia consistently show low levels of acceptance of all three groups as family members compared with other countries in the region. Roughly a quarter in Georgia and Armenia say they would be willing to accept Jews as family members. Acceptance of Muslims is even lower in these countries – 16% of Georgian Orthodox Christians say they would be willing to accept a Muslim family member, even though about one-in-ten Georgians (9%) are Muslim, and just 5% of Armenian Orthodox Christians say they would be willing to accept a Muslim in their family.

About one-in-ten people in Georgia and Armenia say they would be willing to accept Roma in their family, compared with, for example, 30% in Moldova and 18% in Russia.

Muslims in the former Soviet bloc

Pew Research Center previously polled Muslims in the former Soviet republics of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, as well as in the Balkan countries of Albania, Bosnia and Kosovo, as part of a 2012 survey of Muslims in 40 countries around the world. Bosnia and Kazakhstan also were included in the 2016 survey.17

The 2012 survey found relatively low levels of religious belief and practice among Muslims in the former Soviet bloc countries compared with Muslims elsewhere around the world.

No more than half of Muslims surveyed in Russia, the Balkans and in Central Asia say religion is very important in their lives, compared with the vast majorities of Muslims living in the Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia and Africa. Following the same pattern, fewer Muslims in most countries of the former Soviet bloc than elsewhere say they practice core tenets of their faith, such as fasting during the holy month of Ramadan, or giving zakat (a portion of their accumulated wealth to the needy). And considerably fewer in most countries favor making sharia the official law of the land in their countries.

The current survey has large enough sample sizes of Muslims for analysis in Bosnia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Russia. Muslims in Kazakhstan and Russia largely show levels of religious belief and observance similar to those highlighted in the 2012 report. A lack of survey data dating back to the early 1990s on the attitudes of Muslim publics makes it difficult to determine the extent to which these populations have experienced religious revival since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Compared with the Christian populations in Russia, Kazakhstan and Bulgaria, Muslims are generally more religiously observant; higher shares among Muslims than Christians in these countries say religion is “very important” in their lives, report daily prayer and say they attend religious services at least weekly. But in Georgia, where religious observance is higher among the general population than elsewhere in the region, Muslims are about as likely as Christians to say they attend services weekly or consider religion “very important.” In fact, Muslims in Georgia are less likely than Christians to say they pray daily.

In religiously mixed Bosnia, Muslims are more observant than the country’s Orthodox and Catholic populations, and a higher share of Muslims say religion is “very important” in their lives in 2015 than in 2012.