Societal divisions over coronavirus vaccines raised concerns that public belief in the value of childhood vaccines could be negatively impacted. Childhood vaccines protect young children from developing serious diseases over the course of their lifetimes. Vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) are part of the schedule of vaccines recommended for young children by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The Pew Research Center survey finds robust public confidence in the value of childhood vaccines for MMR, with no decline in the large majority who say the benefits outweigh the risks compared with surveys conducted before the coronavirus outbreak.

MMR vaccines have long been the subject of concern among some segments of the public who worry they may be connected with serious side effects. Low vaccination rates in some communities have driven a handful of measles outbreaks in locations across the country over the past decade.

The survey finds important differences across groups in views of childhood vaccines, even as the dominant orientation toward them is positive.

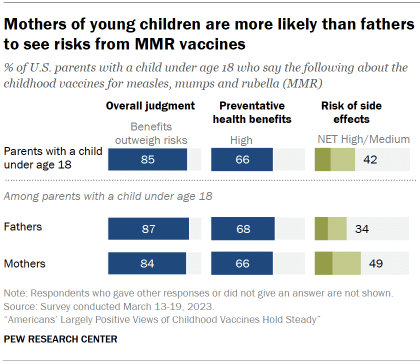

Those closer to the decision-making experience – parents of children under age 18 – are somewhat more likely than other adults to express concerns about the side effects risk of MMR vaccines. Gender is also an important factor. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks, but the potential for side effects is a more salient concern for mothers than fathers.

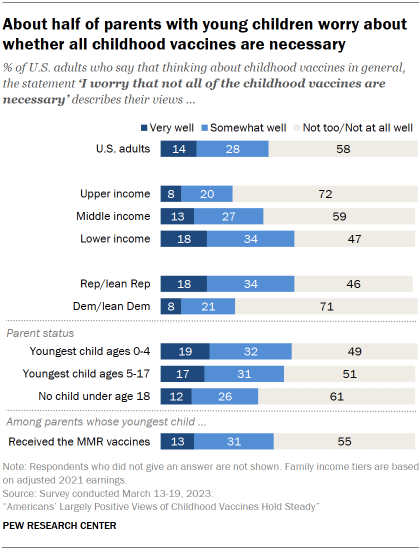

While large shares express bottom-line confidence that MMR vaccines are worth it – and most parents say their own child is vaccinated – the survey also demonstrates that, for many, a degree of doubt exists alongside these attitudes and behaviors. For instance, about four-in-ten say their views are described very or somewhat well by the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary.”

To better understand hesitancy toward childhood vaccines, the report features excerpts from 22 in-depth qualitative interviews with adults who hold some level of concern about vaccines generally. Some interviewees pointed to their belief that childhood vaccines caused adverse reactions in people close to them, when describing the source of their concerns. The challenges of finding trustworthy information on the subject also featured prominently in these conversations. However, many participants drew a distinction between childhood vaccines and those for COVID-19 by stating that the long track record of childhood vaccines for efficacy and safety gave them much greater confidence in them than those developed in the last several years for the coronavirus.

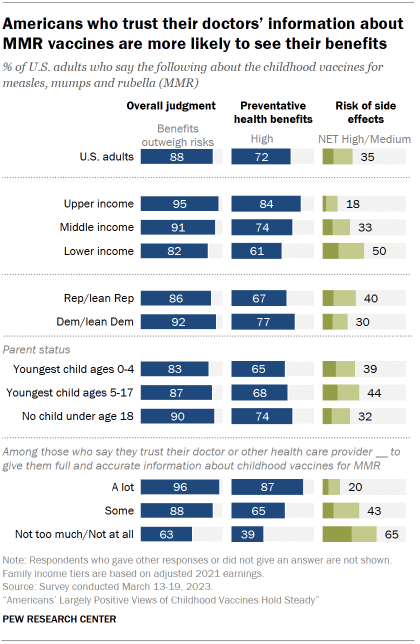

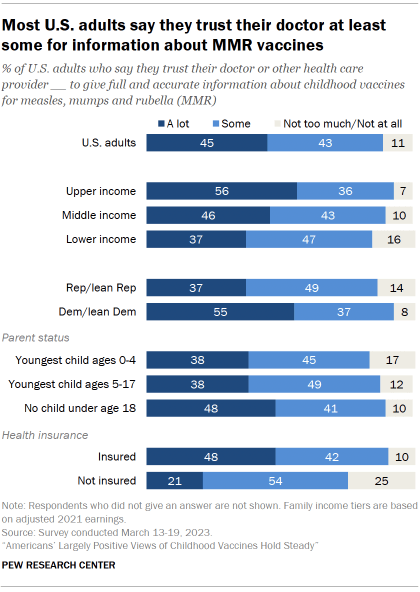

Trust is central to public views of childhood vaccines. The survey shows that adults with the highest level of trust in their own provider to give a full and accurate picture of MMR vaccines express the most confidence in these vaccines and are the least likely to hold concerns about side effects.

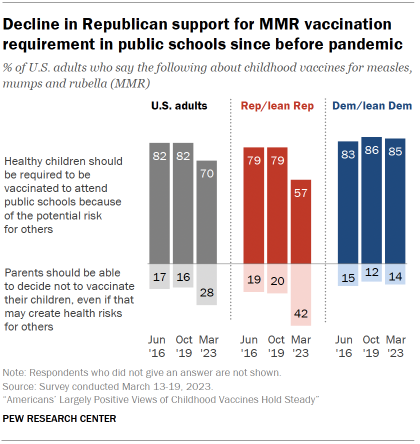

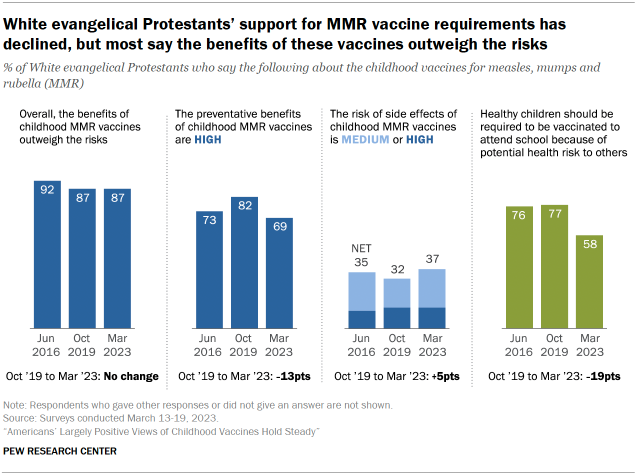

While overall levels of belief in childhood vaccines appear to have withstood anti-vaccine sentiment that formed around COVID-19 vaccines, there has been a significant shift in policy attitudes. A smaller majority of Americans now support requiring children to be vaccinated in order to attend public schools than did so before the coronavirus outbreak. Republicans have seen a sizable decline in the share who support public school vaccine requirements. There’s been a similar drop in support among White evangelical Protestants – a majority of whom identify with or lean toward the GOP. Roughly four-in-ten among both groups now say that parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if it creates health risks for others.

Americans’ positive evaluations of MMR vaccines remain largely steady in wake of debate over coronavirus vaccines

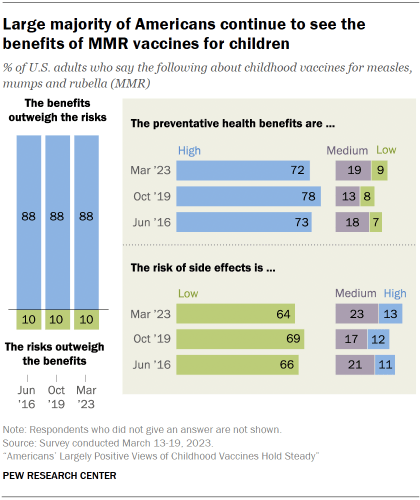

Americans’ overall judgment about the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccines remain overwhelmingly positive with no decline in ratings since the last time they were measured four years ago, prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

Nearly nine-in-ten U.S. adults (88%) say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. This share is the same as when previously asked in both 2019 and 2016.

Separate ratings of the respective health benefits and potential risks of MMR vaccines reflect the public’s positive overall assessment of them.

A large majority (72%) of Americans rate the preventative health benefits of these vaccines as very high or high on a five-point scale ranging from very low to very high. The share of Americans who see the benefits of MMR vaccines as high is down 6 percentage points from 2019 (78%) though it is about the same as in 2016 (73%).

About two-thirds of Americans (64%) say the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is very low or low, while 35% say the risk is at least medium. The share of Americans rating the risk of side effects as low is down 5 points from 2019, though as with ratings of benefits, views on this are about the same as in 2016.

Still, there is some softening in Americans’ certainty around the risks associated with MMR vaccines. In the current survey a smaller share than in previous years rate the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines to be very low. There was also a corresponding increase in the shares rating the risk as either low or medium.

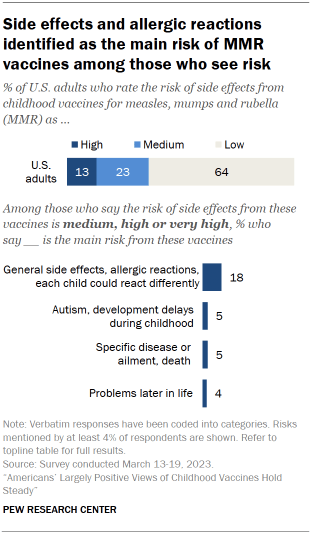

What do people have in mind when they say there are risks from MMR vaccines? The Center survey asked respondents who rated the risk of side effects as either medium or high to explain, in their own words, the main risk they see.

The most common response – given by 18% of those asked – was a general mention of side effects with no further detail provided. Examples of this sentiment include statements such as “harmful side effects” or “adverse reactions.”

One-in-ten of those who see a risk of side effects from MMR vaccines offered a specific concern. Of this group, 5% mentioned autism or developmental delays during childhood. An additional 5% referred to a risk of death or developing any of several diseases such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurological disorders and autoimmune diseases.

A large share of those asked (35%) did not provide a response to this question, while 7% said there were no risks and an additional 6% said they did not know of a main risk from these vaccines.

Partisan differences widen over requiring MMR vaccines in K-12 schools

Americans’ support for school-based requirements for MMR vaccination has fallen since prior to the coronavirus outbreak.

A smaller majority of Republicans and independents who lean to the GOP (57%) now favor requiring MMR vaccination for children to attend public school, while 42% say, instead, that parents should be able to decide not to vaccinate their children, even if it may create health risks for others. Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, the balance of opinion among Republicans favored childhood vaccine requirements (79% vs. 20%).

Democrats’ broad support for vaccine requirements has held steady over the last four years: 85% support school-based vaccine requirements, roughly the same as in 2019 (86%).

As a result of changing views among Republicans, support for requiring childhood vaccines among the general public now stands at 70%, down from 82% when last asked in 2019. The shift among Republicans’ views is in line with a December 2022 KFF update of these Pew Research Center trends.

Parents of children under 18 see slightly higher risks from MMR vaccines than other adults

Parent status is important to consider when analyzing views of childhood vaccines. Those with young children are closest to key decisions about childhood vaccination. While still expressing positive overall views, parents with children under 18 are more likely than other adults to express some concern about potential MMR side effects and slightly less sure that they provide high preventative health benefits.

Among parents of a child ages 4 or under, 83% say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. Among parents with school-age children (ages 5 to 17), 87% view greater benefits than risks. Among adults without children under 18, 90% take this view.

When it comes to independent ratings of the preventative health benefits of MMR vaccines, 74% of adults with no children under age 18 describe the preventative benefits as high, compared with slightly smaller majorities of parents with children ages 5 to 17 (68%) and those with children ages 0 to 4 (65%).

Consistent with this pattern, parents of children ages 0 to 4 (39%) and ages 5 to 17 (44%) are somewhat more likely than adults with no minor-age children (32%) to say the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is medium or high.

Americans’ assessments of MMR vaccines are strongly related to their levels of trust in information from their health care providers. The vast majority of people who say they have a lot of trust in their doctor or other health care provider to provide full and accurate information about MMR vaccines (96%) say that the benefits of the vaccines outweigh the risks, that the preventative health benefits are high (87%) and that the risk of side effects is low (79%).

In contrast, those who say they have not too much or no trust in information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider are much less positive in their views: 63% say the benefits outweigh the risks, and fewer than half (39%) rate the preventative health benefits as high. About two-thirds (65%) consider the risk of side effects to be at least medium.

Income and education are also related to views about MMR vaccines. Half of adults with lower family incomes say there is at least a medium risk of side effects. For comparison, just 18% of upper-income and 33% of middle-income adults consider the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines to be at least medium. Refer to Appendix A for more details.

Mothers are more likely than fathers to see a side effects risk from MMR vaccines. About half of mothers of a child under age 18 (49%) say the risk of side effects is medium or high. Among fathers of a minor child, more describe the risk as low (66%) than as medium or high (34%).

The share of mothers saying the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is at least medium is comparable to the 46% who said this in 2019 but is up 12 points from 2016 (37%). Fathers’ perceptions of the side effects risk from MMR vaccines are about the same as in 2019 (34% medium or high now vs. 31% in 2019). There’s been no increase from 2016, when 40% of fathers said there was a medium or high risk of side effects.

Despite these differences over perceived risk, mothers and fathers hold similar views when it comes to the overall benefits of MMR vaccines: More than eight-in-ten in both groups say the benefits of the vaccines outweigh the risks.

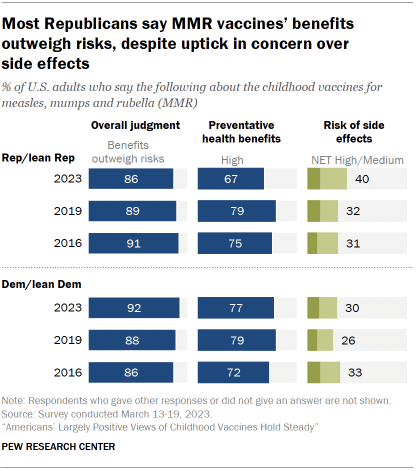

While sizable partisan differences have emerged since 2019 over the question of vaccine requirements for public school children, the views of Republicans and Democrats are more closely aligned when it comes to the overall health benefits of MMR vaccines. Still, even on these measures, slight differences have emerged over the last four years.

Large majorities of Republicans (86%) and Democrats (92%) say that, overall, the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks. Views among these two groups were nearly identical in 2019 (89% and 88%, respectively).

Modest differences have also emerged between partisans in their independent assessments of the preventative health benefits and side effects risk of MMR vaccines. A larger majority of Democrats (77%) than Republicans (67%) now describe the preventative health benefits of MMR vaccines as high. This gap has been driven by a 12-point drop among Republicans in the share who see high preventative health benefits since 2019.

Similarly, the share of Republicans who see at least a medium risk of side effects from MMR vaccines is up 9 points since 2019. There’s been a more modest 4-point shift among Democrats. As a result, there’s now a 10-point difference between the shares of Republicans (40%) and Democrats (30%) who see a medium or high risk from MMR vaccines.

White evangelical Protestants have grown less supportive of vaccine requirements in public schools, but remain confident in overall benefits of MMR vaccines

White evangelical Protestants, a group that leans Republican, stands out among religious groups for its smaller majority who support school vaccine requirements.

The share of White evangelicals who say healthy children should be required to receive MMR vaccines in order to attend public schools has fallen to 58%. Four-in-ten instead say that parents should be able to choose not to vaccinate their children, even if that may create health risks for others. Support for school-based vaccine requirements among this group is down 19 points, from 77%, in 2019.

Still, White evangelical Protestants’ overall judgment that the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh their risks remains quite positive (87% today, the same as in 2019). And among parents of minor children, 82% of White evangelicals say their own child has been vaccinated for MMR, little different from the share of all parents who say this (79%).

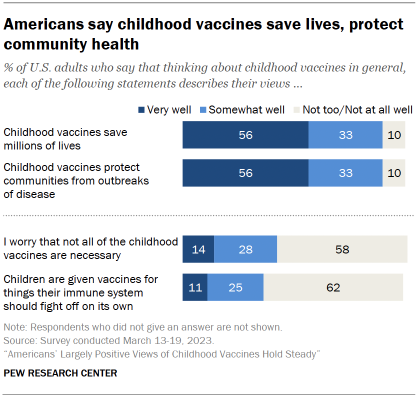

Majorities of Americans see positive societal impact from childhood vaccines, though about four-in-ten wonder if they are all necessary

In addition to their personal belief in the efficacy of childhood vaccines, Americans express broad appreciation for their societal impact.

Asked to respond to a mix of positive and negative statements about childhood vaccines, 56% of U.S. adults say “childhood vaccines save millions of lives” describes their own views very well, while another 33% say this describes their views somewhat well.

The same shares say the statement “childhood vaccines protect communities from outbreaks of disease” describes their views either very (56%) or somewhat well (33%).

Even so, a sizable segment of the public also expresses concern about childhood vaccines. The statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary” describes 14% of Americans very well and 28% somewhat well. And the idea that “children are given vaccines for things their immune system should fight off on its own” resonates with 11% of Americans very well and another 25% somewhat well.

Parents of minors are more likely than other adults to align with statements expressing some concern about childhood vaccines. For instance, among parents with a child ages 0 to 4, about half say their views are either very (19%) or somewhat (32%) well described by the statement “I worry that not all of the childhood vaccines are necessary.” By comparison, smaller shares of adults with no children under 18 say this statement describes their own views very (12%) or somewhat (26%) well.

Mothers are more likely to express this concern than fathers. About half of mothers with a child under age 18 (53%) say the statement “I worry that not all childhood vaccines are necessary” describes their views at least somewhat well, slightly more than the share among fathers (45%).

Family income and education levels are also associated with concerns about childhood vaccines. Those with lower family incomes are more likely than those with upper incomes to express worry over whether all childhood vaccines are necessary. Refer to Appendix A for more details.

In addition, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say this statement describes their views at least somewhat well.

There are similar patterns when it comes to concerns about whether children should fight off disease on their own, without immunity from childhood vaccines. Refer to Appendix A for details.

Most parents report that their children have received an MMR vaccine

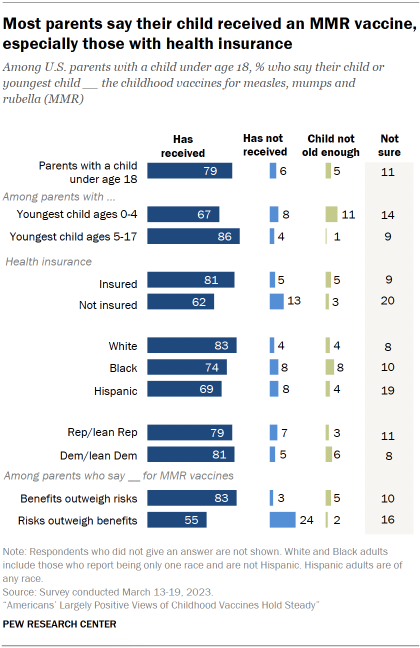

Large majorities of parents with a child under age 18 say they have had their child vaccinated for measles, mumps and rubella.

Two-thirds of parents with a child ages 0 to 4 (67%) say their child has been vaccinated for MMR while 8% say they have not. Another 11% of this group says their child is not old enough to get these vaccines and 14% of these parents say they are not sure whether or not their youngest child had received an MMR vaccine.

A larger share of parents whose youngest child is ages 5 to 17 say their child received MMR vaccines (86%).

The CDC recommends that children receive their first dose of MMR vaccines between 12 and 15 months of age. Parents who have health insurance (81%) are more likely than those with no health insurance (62%) to say their child received an MMR vaccine.

Parents who have health insurance (81%) are more likely than those with no health insurance (62%) to say their child received an MMR vaccine.

Parents’ choices about getting their child vaccinated are closely aligned with their evaluations of the vaccines. About eight-in-ten (83%) parents who say the benefits of MMR vaccines outweigh the risks also say their child has received an MMR vaccine. This compares with 55% of parents who say the risks of MMR vaccines outweigh the benefits.

Majorities of parents across racial and ethnic groups say their child has received an MMR vaccine, though White parents (83%) are more likely than Black (74%) and Hispanic (69%) parents to say this. These differences by race and ethnicity hold when controlling for other factors such as health insurance status.

While Republicans are somewhat more likely than Democrats to express concerns about the risk of side effects from MMR vaccines, there are almost no differences in what the two groups have decided to do when it comes to their own children. About eight-in-ten Republican parents (79%) and Democratic parents (81%) say their youngest child has received an MMR vaccine.

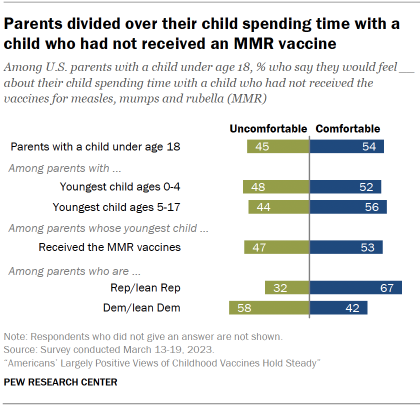

Asked whether or not they would be comfortable having their child spend time with a child who is not vaccinated for the measles, mumps and rubella, 54% of parents with a child under age 18 say they would be comfortable with this, while 45% say they would feel uncomfortable.

Republican parents (67%) are much more likely than Democratic parents (42%) to say they would be comfortable with their child spending time with a child who was not vaccinated.

Attitudes on this question are closely tied to views about vaccine requirements in public schools. About eight-in-ten parents (81%) who oppose vaccine requirements for public school children say they would feel comfortable with their own child spending time with another child who is not vaccinated. Among those who support public school vaccination requirements, fewer than half (38%) would be comfortable with this.

Doctors are trusted at least some as sources of information about the health effects of MMR vaccines

Most U.S. adults say they have a lot (45%) or some (43%) trust in their doctor or other health care provider to give full and accurate information about MMR vaccines.

Parents with a young (ages 4 or under) or school-age (ages 5 to 17) child are somewhat less likely than those with no children under 18 to say they trust their health care provider for information about MMR vaccines a lot. Still, large majorities of each group have at least some trust that their health care provider gives full and accurate information about the health benefits and risks of MMR vaccines.

Family income and education are associated with levels of trust in information from doctors or other health care providers. For instance, upper-income adults (56%) are more likely than middle- (46%) and lower-income (37%) adults to say they have a lot of trust in information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider. Refer to Appendix A for more details on education and additional demographics.

Adults with health insurance coverage also are more likely to express strong trust in the information about MMR vaccines from their doctor or other health care provider (48% vs. 21% of those with no insurance).

Democrats (55%) are more likely than Republicans (37%) to say they have a lot of trust in the information from their doctor or health care provider about MMR vaccines. Related to these attitudes, Center surveys find growing political differences in Americans’ levels of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s interests since the coronavirus outbreak.

Online groups and communities are another potential source of information about childhood vaccines.

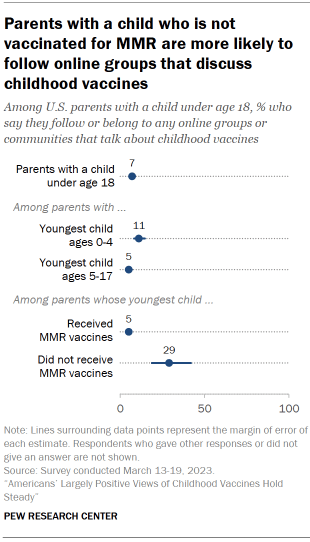

The survey finds that a small share (7%) of parents with a child under age 18 say they follow or belong to online groups or communities that talk about childhood vaccines. Parents with a child ages 0 to 4 (11%) are slightly more likely than parents with children ages 5 to 17 (5%) to say they follow or belong to these groups.

Those most likely to say they are a part of these online groups are the small share of parents who have not vaccinated their child for MMR: 29% of this group say they are a part of online groups or communities that talk about childhood vaccines. Just 5% of parents who have vaccinated their child say the same.

Interviews with those concerned about MMR vaccines reveal desires to rely on multiple sources of information, ones with trustworthy motives

The Center conducted individual, in-person interviews with 22 adults in four metropolitan areas across the nation who had concerns about the safety and effectiveness of either childhood vaccines or COVID-19 vaccines. Among this group, there were 14 parents who expressed at least minor concern about the safety or effectiveness of vaccines typically given to young children for diseases like measles, mumps, rubella and polio.

Participants who expressed little or no concern about the set of vaccines routinely given in childhood today often drew contrasts between their perceptions of the proven track record of the MMR and polio vaccines for safety and effectiveness, compared with their concerns along these dimensions tied to COVID-19 vaccines and their rapid development.

Some participants also reflected that long-standing social norms to get childhood vaccines when they were growing up and when their children were young may have contributed to their confidence in these vaccines. In reflecting on her experiences as a parent, one woman said about health care providers:

“I mean, they were the ones that told me when to get vaccinated, and I trusted the pediatrician and we kind of went on their schedule of everything. And my pediatrician was very pro-vaccine, so I listened to her.” – Woman, age 50-54, Phoenix, Arizona

“It was just, this is what the doctor says you’re supposed to do and I never even thought twice about it.” – Woman, age 50-54, Cincinnati, Ohio

Newer vaccines raised more questions for one of the participants.

“There’s a few new vaccines that they’re requiring [for] kids, and the last one we let them get was the chickenpox. And we were like, why do they have a chickenpox vaccine? I had chickenpox, you had chickenpox, we had chickenpox parties when somebody had chickenpox, so you’d go ahead and get it, and get it out the way. So now why is the chickenpox vaccine being required? So [my wife’s] alarms went off, ‘I don’t trust that.’” – Man, age 45-49, Jacksonville, Florida

And a few of those interviewed expressed a desire to spread out childhood vaccines a bit more than the recommended schedule.

“The combination of all those vaccines at one time, I don’t know how your body and your immune system can identify that, and then prevent anything from happening. I feel like that’s too much for a little human’s immune system to even grasp.” – Woman, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“So we had our son on a delayed [vaccination] schedule, and the mindset around that was basically, which ones are the most at risk for where we live? And which ones are the most severe if contracted? For example, meningitis can kill you, for everyone. So that was like, ‘All right, well, let’s do that,’ when the doctor or his physician recommended it. So yeah, my mindset around vaccines for children is trusting them because of the history and longevity, but then also not really strict pump them up with everything all at once.” – Man, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

Some of the strongest concerns expressed by interview participants about childhood vaccines related to adverse health experiences in their family or among their friends

The set of interviewees who raised strong concerns about the MMR or other routine childhood vaccines reported that they, a child in their family, or someone else in their close circle had an adverse reaction to a vaccine in the past. These experiences lead to increased scrutiny of and skepticism of childhood vaccines, generally.

One father who explained that his daughter experienced severe developmental issues which he saw as linked to getting the diphtheria and MMR vaccines at 18 months of age was explicit in saying, “Me and my family as a whole, we’ve been very much pro-vaccine until we had the problems with it.” But the experience led to increased scrutiny of information related to vaccines, generally. He explained:

“So we’ve gone very far into looking at the actual studies done on them and we will search out even within studies, the specific citations, trying to find different articles and compare them all.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

A mother from Phoenix, Arizona, spoke of her change in views because of her daughter’s adverse reaction to a Vitamin K shot as well as other childhood vaccines which lead to a diagnosis of an autoimmune disorder. She explained her search for reliable information this way: “I do refer a lot to the Internet. But I do try to pull from multiple sources. So while I may just Google something, I will do it in many different fashions on many different platforms, and compile different information, puzzle piece that together to make my own informed decision.”

She talked about the need to find a pediatrician who would listen to her family’s concerns, saying when it comes to childhood vaccines:

“I again, think it’s important to interview your doctors as well as you would interview a child care provider, so that you have that trust factor with that person. Because doctors are human, and they do have their personal opinions. And if they’re going to push their personal opinion as their professional opinion, that’s not necessarily fair to you as a patient.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

Internet searches and social media sites eyed with a healthy skepticism but so too are news media sources, medical professionals

Interview participants were asked to describe the sources of information they found more and less credible. Many said it was challenging to determine trustworthy sources. Some of those interviewed spoke of drawing credibility when they gathered independent sources that told a consistent story. Several pointed to the motivations that might be driving the provider of information as another factor they considered.

Some examples of how people parsed different sources of information:

“Mommy bloggers are one of the big things that are out there. Those are personal opinions, not actual factual information. I also know that the pamphlets that are handed out at the pediatrician’s office are supplied by the vaccine manufacturer, not necessarily by a credible source. They do push their agenda, not necessarily what is out there. So taking that information and then doing your own continued research on top of it, asking questions, being informed, is [in] my opinion, the best way to go.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

“So as much as I hate to say this, anything directly from the manufacturers, because at the end of the day that is their product. And I’m not saying it’s not credible, but it becomes instead of trust, it moves more into my trust but verify. … You got to look at where everything’s coming from and what the motivation behind it is.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“I think anything we hear on the news is not reliable at all. That is totally the most unreliable information. Anything on the Internet, unless it is a .gov website, I find totally unreliable. Anything that could be manipulated, like Wikipedia, where people can change the information, that’s not reliable. So I think anything that ends in .org or .gov could be credible. Anything outside of that? Not at all.” – Woman, age 25-34, Cincinnati, Ohio

“This could be also ignorance, but I think with my experience on the Internet, I think if I did enough research of my own on the Internet, that I could find enough sources that would match that I could then trust that information. Because I feel like that’s just a problem with the news. We have five news sources on TV, five different stories come out about the same story. If you go online, you can say, ‘OK, I found five different sites that are not just like mom and pop sites that are popular sites, and they’re all reporting the same information.’ So to me, that feels credible.” – Man, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona

Social divides over vaccines can cause emotional pain as well as frustration

Interviewees with strong concerns about childhood vaccines also spoke to some of the difficulties they experienced getting health care from providers:

“Yeah, three pediatricians later. I mean, it was a fight. It was anytime I came in for anything stupid, small stuff, it was always like, ‘Oh my gosh, well, they’re not vaccinated.’ I’m like, ‘But that’s not what I’m here for.’” – Woman, age 35-44, Seattle, Washington

“We actually were dropped from a pediatrician’s office when we said that we had concerns about vaccines and we didn’t want to continue on and laid out our specific worries and the specific reactions our kids have had. They said that they would not allow patients under their care who were not vaccinated, which really upset us because we’re like, ‘OK, but we’re explaining why.’ And their answer was simply, ‘We understand that, but if you want to have your kids remain unvaccinated, then you can’t use us as the provider anymore.’” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

A reoccurring theme among these interviewees regarding what bothers them most about the issue of vaccines was a frustration with the social divisions over vaccination and the inability to have an open conversation about them.

“The same thing that bothers me about most controversial topics these days, is the fact that we as a society have gone from a group of people who can discuss our opinions and why we feel that way about something to, it seems like you’re either on one side or the other. You’re not allowed to be in the middle.” – Man, age 25-34, Phoenix, Arizona

“Personally, I have been in situations where people have flat out told me that I was a bad parent for doing the things that I do or have chosen to disassociate themselves with parts of the family because they don’t believe in vaccinations, or they don’t believe in the COVID-19 vaccination.” – Woman, age 35-44, Phoenix, Arizona