Women earned 84 cents for every $1 made by men in 2012, according to a new report released today by the Pew Research Center.

How did we get to that number? In October, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that women earned 81 cents to the dollar. The difference is not large, but what gives?

One reason is that our study estimates the gender gap in hourly earnings while the government estimates the gap in weekly earnings. We chose to use hourly earnings, estimated as usual weekly earnings divided by usual hours worked in a week, because it irons out differences in earnings due to differences in hours worked.

For example, women are twice as likely as men—26% versus 13%—to work part-time. Naturally, that has a significant impact on the relative earnings of women and men if one looks at weekly earnings. To account for the skew in hours worked, the government’s estimate of the gender pay gap is derived for full-time workers only, defined by the government as people who usually work at least 35 hours per week.

Restricting the estimate of the gender pay gap to full-time workers is not without limitations. For one, it leaves out a significant share of women and men when calculating the gender pay gap, namely those who work part-time. Moreover, just looking at full-time workers does not eliminate the difference in hours worked. Even in this group, men report working longer hours—26% of full-time men say they work more than 40 hours per week compared with 14% of women, according to government data.

The BLS, of course, is aware of these limits and it reports several other measures of the gender pay gap—for workers paid by the hour, for part-time workers, and for workers grouped by the number of hours worked in a week. According to their data, women who are paid an hourly rate earned 86% as much as men who are paid an hourly rate; women working part-time earn 104% as much as men working part-time; and, at the extreme, women who worked five to nine hours in a week earned 119% as much as men who worked the same number of hours. The reasons why women who work fewer hours earn more than men are complex, but a contributing factor is that women who work part-time are older than men who work part-time.

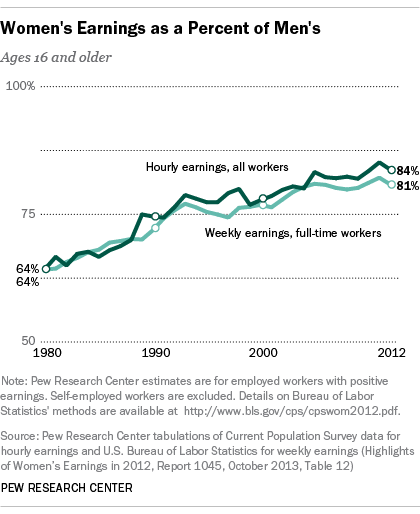

As it turns out, our estimates are similar to the government’s estimates, not only for the moment but over an extended time. The BLS reports that the weekly earnings of full-time women relative to weekly earnings of full-time men increased from 64% in 1980 to 81% in 2012. Our estimate, based on hourly earnings of women relative to men, shows an increase from 64% in 1980 to 84% in 2012. In the intervening years, the two estimates trend together very closely.

Which is the preferred basis for the gender pay gap—weekly earnings or hourly earnings?

The two measures offer different perspectives, and, like many other things, the choice is with the beholder. Those wishing to focus on specific segments of the labor market may prefer the several different estimates broken down by the BLS. Those wanting to focus on the overall figure for working women and men may prefer our more encompassing approach, which uses hourly earnings.

Regardless, the pay gap estimates show that women earn 16-to-19% less than men. What explains this gap in the earnings of women and men?

Some of it is due to differences in the types of jobs (occupations) women and men do and some of it is due to the effects of parenthood on women and men. Research also suggests that women may not negotiate for higher wages as aggressively as men or they may be more likely to trade off higher wages for other amenities, such as flexible work hours. Other pieces of the puzzle—attributes employers value but that are not captured in available data or the presence of discrimination—are more difficult to quantify.