The Pew Research Center released on Thursday our 2014 political typology, including the newest version of our political typology quiz, in which users can see where they fit in the current political landscape by answering 23 questions about core political values. Within the first 24 hours, more than 90,000 people had taken the quiz, and the last quiz, launched in 2011, had over 1.5 million users over three-plus years.

One of the strongest reactions we have received from some quiz-takers is frustration over the either-or choices each question offers. Many of the comments we’ve received say that the questions feel like choosing “between two extremes,” or that the “right answer is somewhere in between,” or that the options “aren’t really opposites.”

These are all legitimate concerns, and many of our own early users here on the Pew Research Center staff expressed the same frustrations. But there is a reason the questions are asked the way they are: The intent is not to put people “in a box” but rather to understand how their values across multiple political dimensions are related to each other.

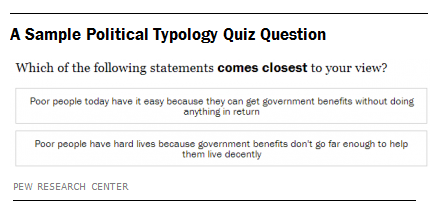

Take a question like the one shown here. For many Americans, the two options present a very stark way of thinking about poverty, and it is a fair guess that many people have some level of agreement with both points of view. At the same time, this “forced choice” format reflects a fundamental debate in American politics right now, and most people at least lean one way or the other on this potentially difficult tradeoff. In fact, the American public as a whole splits almost exactly in two on this question – 44% select the first statement, 47% pick the second – and their choice is strongly related to their specific policy preferences and priorities in this realm.

One frustration of a question like this is in its bluntness. It can make a respondent feel as if they are being lumped in with a bunch of people who hold much more extreme views than they do.

But the “forced choice” construction of this question (and others) is part of its design. The question picks up on which of two statements on a core value people lean towards, and does not necessarily presume complete agreement with a question. That is why the instructions ask, “Which comes closer to your view, even if neither is exactly right?”

And because the typology quiz includes 23 questions, many of which measure closely related concepts—for instance, there are three more questions in the quiz that pick up on the same theme about the relationship between government and support for the poor—no one statement alone dictates which group you’ll end up in. So even if some questions are not a great fit for your values, the combination of responses should place you in a group that reflects your underlying political type.

Put differently, while individual questions may not allow for nuance, the combination of questions does. In fact, that is part of what the cluster analysis approach we use to define the typology does.

In addition, this year’s typology builds upon the 20-year Pew Research Center history of asking many of these specific questions. Some of these questions use language that is different from how we might ask them if we were developing them for the first time this year. But there is a great deal of value in maintaining identical question wording in order to measure change over time, even if the wording used in the past is not ideal today. Because of the 20 year history with this series of questions, we were able to document the growing amount of ideological consistency in peoples’ thinking over the period.

Finally, it’s worth emphasizing that we do not see these questions as measures of political “extremism.” Instead, these forced-choice questions were designed to capture enduring political values that underlie the policy preferences and partisan choices people make in politics. And our goal is to get a picture of how peoples’ values are organized, not how strongly they hold those views. There is a very important distinction between ideological values and more radical political thinking, and we address this distinction in our earlier report on political polarization.