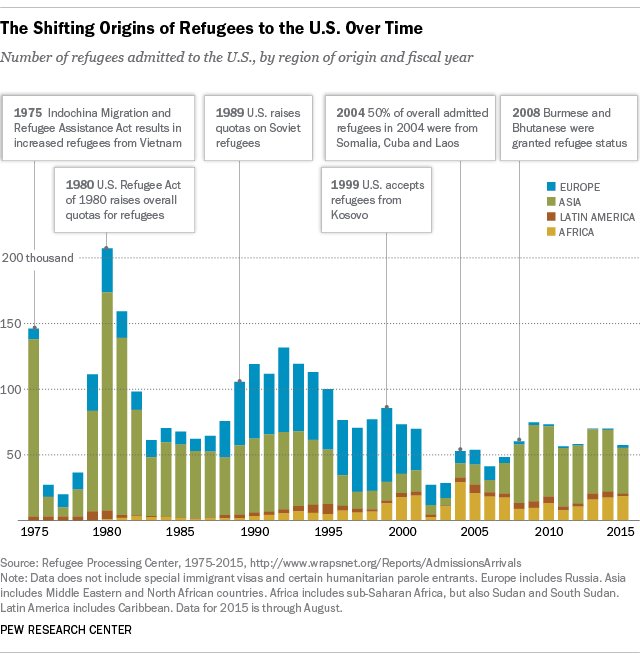

This week, Secretary of State John Kerry said the U.S. would resettle 85,000 global refugees in the coming fiscal year and 100,000 in fiscal 2017, marking a significant – though far from historic – increase in taking in the world’s most desperate.

Conflicts in the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere are driving hundreds of thousands of refugees to Europe, creating a humanitarian crisis that European leaders have been struggling to manage. Pope Francis has called on Europe’s Catholics to do more to house refugees, and he is expected to address the issue again during his current U.S. visit.

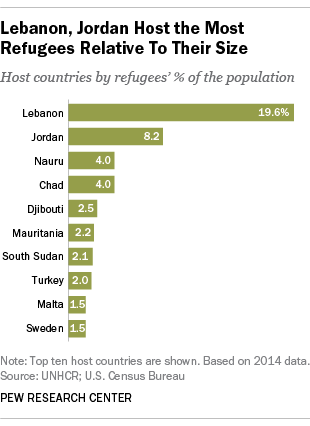

The U.S. ranks 14th worldwide in the number of refugees it hosted last year (267,174), according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees – though that represents less than 1% of the nation’s population. (The UNHCR figures represent the total number of refugees living in a country at year end who have not yet been permanently resettled there, regardless of when they arrived.)

For the past three fiscal years, the U.S. has capped the annual number of refugees it will accept at 70,000. Of the 57,350 refugees admitted so far this year, most have come from Burma (13,831), Iraq (10,898) or Somalia (7,642). Since 1975, according to data from the State Department’s Refugee Processing Center, more than 3 million refugees have been admitted to the U.S.

Aside from policy, the U.S.’s ranking could be explained in part by geography. A new Pew Research Center analysis finds that countries facing the biggest impacts from refugees today are the ones closest to political or war-torn instability.

When we looked at which countries are hosting the most refugees relative to their populations, Lebanon was far and away the leader. Our analysis, which used 2014 data from the UNHCR and international population estimates from the Census Bureau, found that the 1.15 million refugees in Lebanon last year – nearly all of them fleeing the civil war in neighboring Syria – represent nearly 20% of that country’s population of 5.9 million. In second place was Jordan, where refugees – also nearly all from Syria – represent more than 8% of the population.

In raw numbers, Turkey hosted more refugees than any other country last year: almost 1.6 million (or about 2% of the country’s population), including more than 1.5 million refugees from Syria and about 25,000 from Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. (The total number of refugees in Turkey has since grown to 2 million, but they’re not allowed to seek permanent asylum there. Some experts say Turkey’s policy contributes to the surge of refugees into European Union countries with more liberal asylum standards.)

Other nations adjoining conflict zones with significant refugee populations relative to their populations are Chad (4%), which borders Sudan; Djibouti, next to Somalia (2.5%); and Mauritania (2.2%), which is sandwiched between two conflict areas, northern Mali and Western Sahara.

The data showed one special case: Nauru, a Pacific island nation with fewer than 10,000 residents. Last year, Nauru hosted 381 refugees (equivalent to 4% of its total population) along with 720 asylum-seekers, most of them from Iran, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Why? Since 2012 (and earlier from 2001 to 2008), Australia has paid Nauru to operate a detention center for refugees and asylum-seekers who’ve tried to enter Australia by boat – a practice that has come under fire there.

We based our analysis on data that use globally accepted definitions of refugees and asylum-seekers. The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees defines refugees in general as people who have left their home countries due to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

The UNHCR defines asylum-seekers are persons who have applied for asylum or refugee status, but who have not yet received a final decision on their application. (This would apply, for instance, to the people who’ve been hiking across European borders or crossing the Mediterranean by boat seeking entry to EU countries, once they’ve made a formal application for asylum).

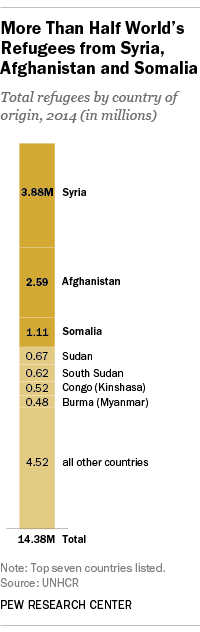

More than half (53%) of the 14.4 million counted by the UNHCR last year are from just three countries – Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia, which together accounted for nearly 7.6 million refugees.

The UNHCR dataset, it should be noted, does have some limitations. For one thing, it excludes 5.1 million Palestinians (refugees from the 1948 and 1967 wars, along with their descendants) in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Jordan and Syria, who are served by the UN Relief and Works Agency. (However, nearly 100,000 Palestinians living elsewhere are included in the UNHCR counts.) In some cases, such as when only a few refugees from one country are in a particular host country, the exact figures have been kept confidential to protect their anonymity.

Also, once people have been permanently resettled in a new country (or return to their old one), they’re no longer considered refugees. According to the UNHCR’s latest “Global Trends” report, last year 105,200 refugees were admitted for resettlement in 26 countries (with or without the agency’s assistance), while 126,800 refugees returned to their countries of origin.

The refugee counts also don’t include “internally displaced persons” (IDPs) – people who have been uprooted from their homes by “armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural- or human-made disasters” but are, for the time being at least, still within the borders of their home countries. Estimates of the number of internally displaced people last year range from 32 million to more than 38 million; according to the UNHCR data, Syria, Colombia and Iraq together accounted for 17.3 million IDPs.