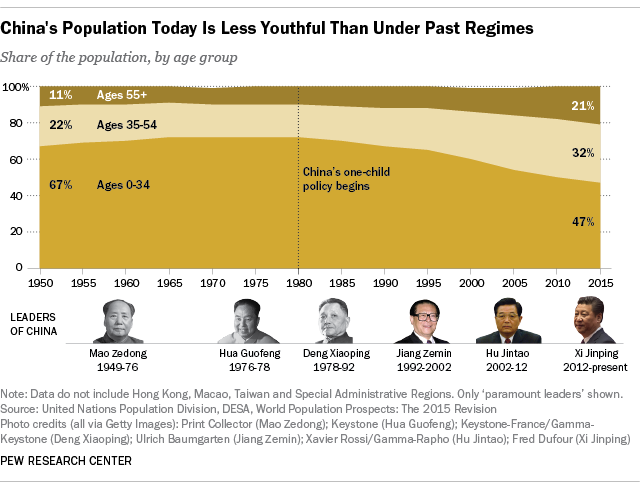

The year 1980 in China is well known as the beginning of the country’s one-child policy. But what may be overlooked is how that year also marked a turning point in China’s generational experiences: Roughly half (47%) of China’s current population were born under the policy (ages 0 to 34 today), and they lived through a very different China than the half who were born before.

Indeed, there’s much discussion in Chinese media about the “post-1980s generation,” a label used to describe a group of people born immediately after a series of sweeping political, economic and cultural changes.

Members of the post-’80s generation (八零后) were born after the death of Mao Zedong, and after Deng Xiaoping took power and opened up China’s economy for reform. They came of age during China’s economic boom, and this generation serves as a reference point to describe a group of people (mostly in cities) who lived through significant cultural shifts – much as Baby Boomers and Millennials do for the U.S.

Those from this post-Mao, only-child generation, often called “little emperors,” are said to be spoiled and privileged, having not lived through food rationing or other hardships like their parents did. They’re criticized for being materialistic and rebellious, with unprecedented access to consumer goods and exposure to global pop culture – though they gained praise for their extensive earthquake-relief efforts in 2008. They’re also educated and tech-savvy (like the post-’90s and following generations) and have access to more information and social networks than ever before. Their most famous members include NBA player Yao Ming, young-adult novelist Guo Jingming and outspoken blogger Han Han.

The other half of China’s population (ages 35 and older, making up about 53% of the population) were born before the country’s one-child policy was widely implemented in September 1980, according to Pew Research Center’s analysis of United Nations data.

These older Chinese lived through a volatile era that included the civil war (ending in 1949), the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960), the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and other radical movements. They were part of a more agrarian society, with many living in poverty. They were also part of a younger society: Data show that 72% of China’s population during the Cultural Revolution were ages 34 and under, including about 60% who were ages 24 and under.

The pre-’80s generations were part of a China that was more hostile to foreign countries, including the United States. Many came of age during an era when China closed down its borders to trade and travelers and condemned Western ideas. By contrast, the post-’80s and ’90s generations grew up in societies that were more engaged with international trade and exposed to U.S. culture.

This divide is evident in public opinion: Younger people in China, though still patriotic, view the U.S. more favorably than their elders, according to our spring survey this year. A majority (56%) of Chinese ages 18 to 34 give the U.S. a positive rating, while just 37% of older Chinese (ages 35 and older) view the U.S. favorably.

Nonetheless, there are many attitudes that Chinese of all ages share today: Life is better now than it was in the past, and China’s current economy looks solid. No matter their age, nearly all Chinese adults say their standard of living today is better than their parents’ when they were the same age. And a large majority of young and old Chinese (seven-in-ten) say their personal economic situation is good.