Millions of people across the East Asia Pacific are moving to cities, and nowhere more so than in China, where the urban population expanded by 131 million from 2000 to 2010, according to research from the World Bank.

But unlike other nations in the region, many of China’s urban areas have become less crowded (losing population density) in that time period, spurred by government policies that encourage rapid building. In the most unique cases, this has led to the creation of so-called “ghost cities,” where new urban infrastructure sits idle, waiting for the first inhabitants to arrive.

The extent of urban building in China can be studied in innovative ways, as seen in the World Bank report, which dispenses with traditional, administrative approaches to calculating urban populations and instead uses satellite imagery and census micro-data to measure urban density. The study defines urban areas as contiguous lands with 50% or more of the area covered by built-up infrastructures such as roads and buildings, and whose overall population was 100,000 or more in 2010.

The data show that China added 23,700 square kilometers of urban land in the first decade of this century, by far the most in East Asia Pacific. The 17 other nations in the region added just 4,800 square kilometers of urban land combined.

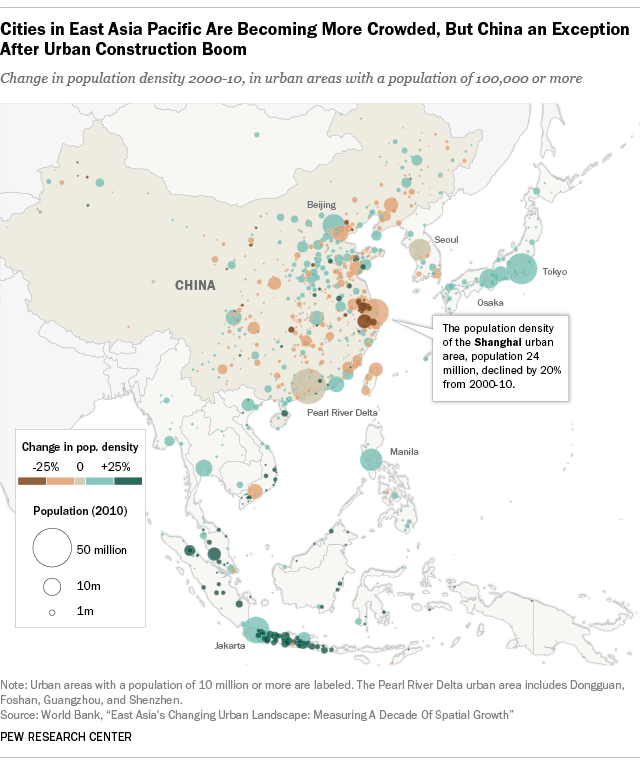

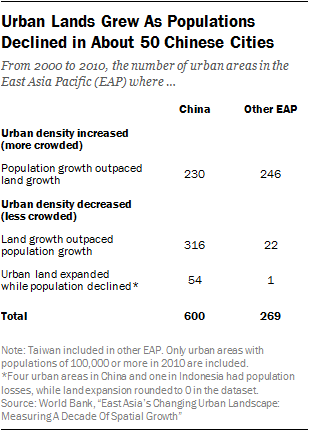

The rapid build-out of urban infrastructure has led to a situation in which 62% of urban areas in China with populations over 100,000 actually became less crowded (meaning they lost population density), even as most of them gained in total population. The simple math means that new construction rates in building out these cities outpaced the rates in which people were moving in. By contrast, just 9% of urban areas in other East Asian Pacific nations became less crowded.

For example, in the Shanghai urban area, which was relatively crowded to begin with, urban acreage increased by 117% (from 1,600 square kilometers in 2000 to 3,500 in 2010), while the area’s population grew at a lower rate of 73% (from 14 million to 24 million) – a net loss in density.

In extreme cases, about 50 of the smaller urban areas (map) in China were constructing more roads and buildings even while their populations declined from 2000 to 2010 – a phenomenon that has rarely occurred elsewhere in the region. This dynamic of more buildings and roads but fewer people likely leads to a larger share of structures sitting vacant.

Some of the most populated of these areas include Jiamusi in Heilongjiang province, one of the most northeastern cities in China; Jixi, a coal hub also in Heilongjiang; and Xinji, a factory town in Hebei province that’s dominated by the tanning industry.

Since 2009, the news media have taken interest in China’s ghost cities, known colloquially as guicheng (鬼城). These newly built, dystopian-looking cities – such as Kangbashi in Ordos City and Shenfu New Town in Liaoning province – have sophisticated urban infrastructure but very few people. While anecdotal and photographic evidence shows that these cities feel virtually empty, their populations are often too small to appear in the World Bank data, or they are considered parts of larger urban areas.

The phenomena of ghost cities and empty neighborhoods are driven largely by administrative decisions, according to a 2014 report by the World Bank and China’s State Council. It’s relatively inexpensive for local officials to expand their cities by converting rural lands, and sales of these lands for commercial or residential purposes often result in income gains for the local areas.

There are some caveats to the World Bank’s 2000 to 2010 data: Some urban areas, like Shanghai, were difficult to discern from the broader network of urbanizing areas surrounding it. And population density figures often mask internal variations within each area measured, for example, if people moved into denser city centers rather than the newly built neighborhoods on the outskirts. It’s also worth noting that total urban density – when you add up all the change across all the cities – has been stable in China.

The World Bank hopes to use satellite images in the future to look at urban growth in regions outside of the East Asia Pacific, and eventually worldwide, according to Judy Baker, lead economist at the World Bank’s Urban Practice Group.