Many Europeans are questioning their respective countries’ role in the world after contending with years of economic struggle, coping with waves of refugees, feeling under siege from terrorist attacks and facing a newly assertive Russia. A new Pew Research Center survey of 10 European nations finds a population looking inward, although views across the continent differ on specific questions such as the importance of global engagement and which issues constitute the greatest threats.

Here are six key findings from our survey:

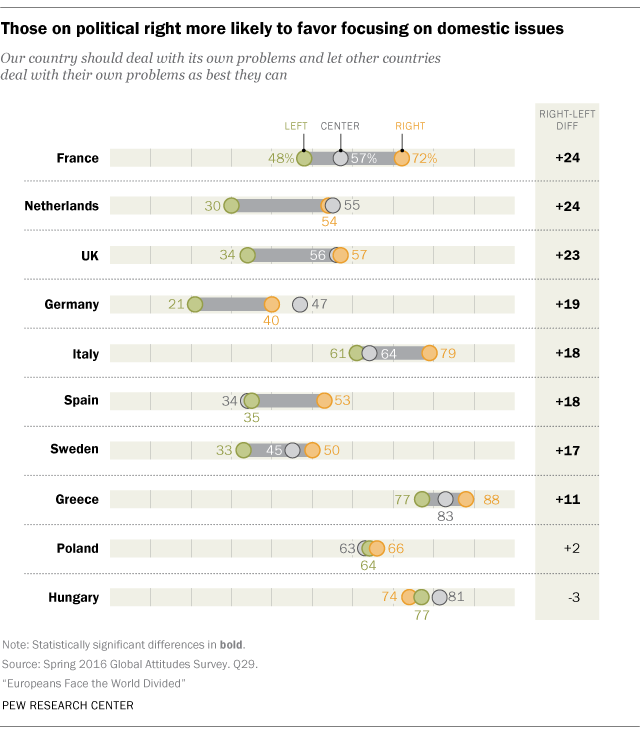

In seven of 10 EU societies surveyed about half or more of the public believes that their country should deal with its own problems and let other nations fend for themselves as best they can. Fully 83% of Greeks, 77% of Hungarians, 67% of Italians and 65% of Poles believe their countries should focus on their own challenges. Only in Spain (55%), Germany (53%) and Sweden (51%) do about half or more believe their country should be helping other nations. For many Europeans, global engagement is an ideological issue. In eight of 10 nations people on the right of the political spectrum are more likely than those on the left to voice the view that their country should deal with domestic problems as opposed to helping others.

This is a particularly strong view held by those on the right in Greece (88%), Italy (79%) and France (72%). At the same time those on the left in Germany (70%), Sweden (66%) and the Netherlands (65%) especially favor assisting other countries.

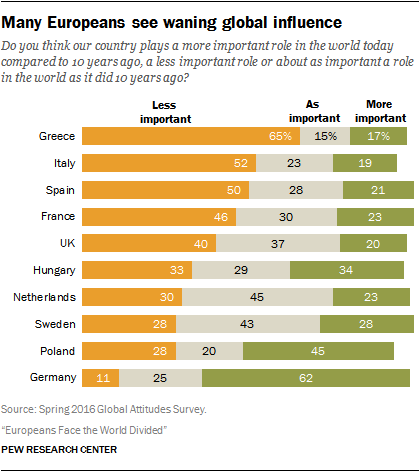

Waning confidence in global importance afflicts a number of European nations. Only the Germans (62%) and the Poles (45%) believe their countries play a more important role in the world today compared with a decade ago. Roughly two-thirds (65%) of Greeks, about half of Italians (52%) and Spanish (50%), and a plurality of French (46%) say their nations now play a less important part on the world stage.

A majority of Germans of all ages express the opinion that Germany is now more powerful than it was 10 years ago. In Poland, about half of the young (52%) see their country as more important, but only 37% of those ages 50 and older agree. In contrast, the young, the middle aged and older people in Italy, Greece and Spain all believe that their nation is less important than it was 10 years ago.

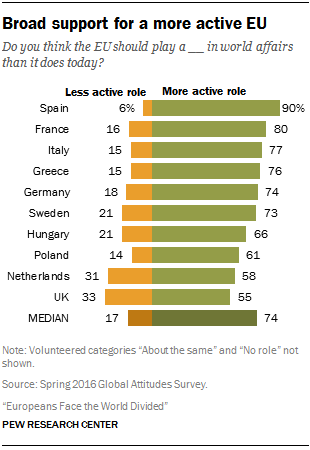

Europeans want the EU to play a bigger role on the world stage. While most in the survey are downbeat about the European Union’s recent track record within Europe, they have a more optimistic view of the EU’s future global role. A median of 74% of Europeans want the EU to take a more active international stance in the years ahead. The most support for a less active EU is in the UK and the Netherlands, yet even in these countries only a third or fewer hold this view.

Such public sentiment reflects a contrast between a fairly negative assessment of the EU’s handling of key problems and public hopes for the EU’s future role in the world. This may, in part, be explained by people’s idealism about the EU’s potential. A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that strong majorities in seven EU nations believed the EU promotes peace.

Europeans clearly see ISIS as the top threat to their countries. Among eight potential threats asked about, roughly seven-in-ten or more in every country surveyed named the Islamic militant group ISIS as a major threat, with the greatest concern coming from the Spanish (93%) and French (91%). There were sharper divides about the level of threat posed by refugees from nations such as Syria and Iraq. Roughly two-thirds or more in Poland, Hungary, Greece and Italy see the refugee issue as a major threat. By contrast, much smaller shares of those in the Netherlands (36%), Germany (31%) and Sweden (24%) agree.

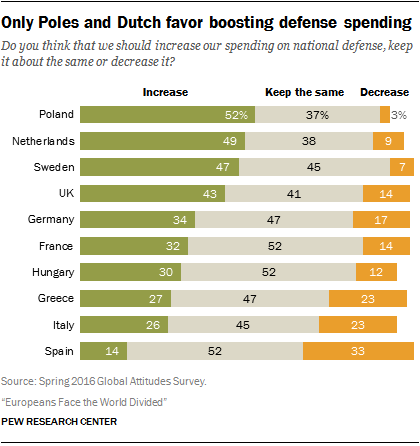

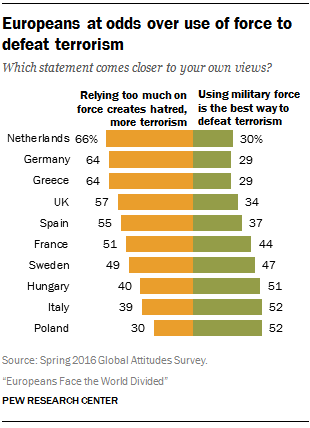

Many Europeans have an aversion to the use of military power in international affairs. There is little backing among Europeans for boosting defense spending, and many believe that relying too much on military force to defeat terrorism only creates hatred that can lead to more terrorism.

Despite commitments by their governments to boost military spending, roughly half the public in France (52%) and Spain (52%) wants to keep defense spending the same as it is today, as does a plurality in Germany and Greece (both 47%). A third of the public in Spain and about a quarter in Italy (23%) favors cutting military outlays. Only in Poland and the Netherlands does even about half the public back more defense spending.

The Dutch (66%), Germans (64%) and Greeks (64%) share a concern that a strong military response to terrorism will only worsen the problem. At the same time, roughly half of the Poles (52%), Italians (52%) and Hungarians (51%) believe that using overwhelming military force is the best way to defeat terrorism.

As might be expected, there is a deep ideological divide on this issue. About half or more of people on the right of the ideological spectrum in Italy, Sweden, France and Spain support exercising overpowering military might. At the same time, people on the left for the most part are far more concerned than people on the right that such use of force would further provoke terrorists.

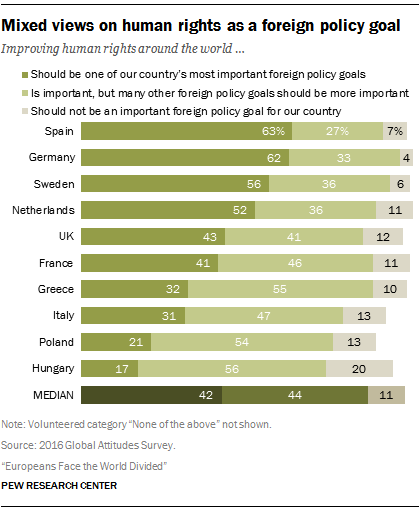

Europeans show mixed support for “soft power” initiatives such as promoting human rights and foreign aid. A median of just 42% believe that human rights should be a top priority for their country’s foreign policy. And a median of only 53% support their government increasing foreign aid to developing nations.

There are deep ideological divisions on the human rights question, with those on the political left much more likely to consider human rights a top foreign policy priority. This is especially true in the UK, where 72% of those who place themselves on the left of the ideological spectrum say improving human rights should be one of Britain’s most important foreign policy goals, compared with just 32% of those on the right. Double-digit gaps between left and right are also found in six other nations.

Roughly half or more of the public expresses support for increasing foreign aid in seven nations. The greatest support is found in Spain (83%), Germany (67%) and Sweden (61%). But 69% of Greeks and 64% of Hungarians oppose such action, as do 51% of the British.

Attitudes toward foreign aid are also linked to ideology. People who place themselves on the political left are more supportive of increasing aid than those on the right in five nations. In France, the UK and Germany, the left-right gap is more than 20 percentage points.

Related: Public Uncertain, Divided Over America’s Place in the World

NOTE (April 2017): After publication, the weight for the Netherlands data was revised to correct percentages for two regions. The impact of this revision on the Netherlands data included in this blog post is very minor and does not materially change the analysis. For a summary of changes, see here. For updated demographic figures for the Netherlands, please contact info@pewresearch.org.