For millennia, humans have been dreaming about vaulting past our biological limits, from natural constraints on our intellect and physicality to our very mortality. But now, according to some researchers and futurists, we may be on the cusp of a scientific revolution that could give each of us an opportunity to cross these boundaries and live longer and stronger than any human being before us.

And yet, a pair of Pew Research Center surveys on life extension and human enhancement show that many U.S. adults are not ready to embrace these possibilities, whether it be in their own lives or in society more broadly.

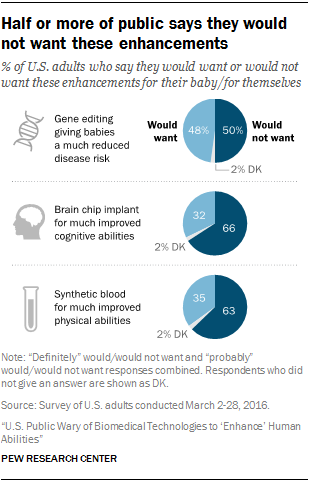

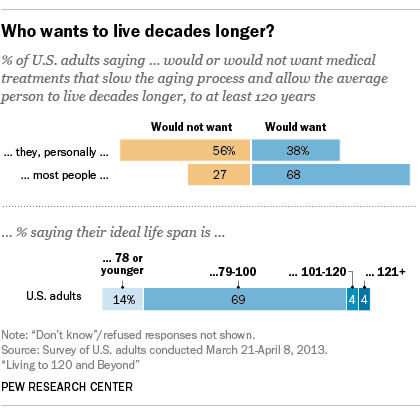

In our 2013 survey on radical life extension, 56% of adults said they would not want to live at least 120 years, which is considered the current upper limit of the human life span. Likewise, roughly two-thirds of adults in our 2016 poll on human enhancement said they would not want a brain chip implant to improve their cognitive abilities (66%) or synthetic blood to augment their physical abilities (63%). American adults were somewhat more open to the possibility of using gene editing to reduce the risk of serious disease in babies, with 48% saying they would be interested, but a similar share (50%) said they would not want to use the technology on their baby.

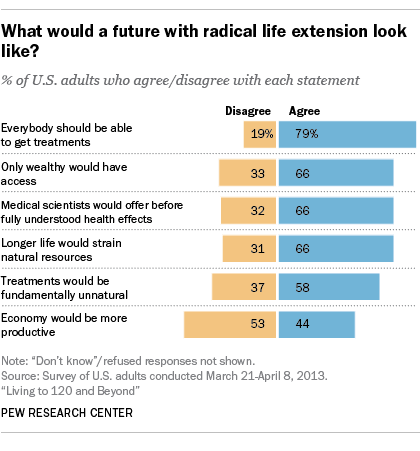

For many people, both potential advancements also raised concerns about increasing social inequality. Two-thirds of those polled about radical life extension thought the option would only be available to the wealthy. At least as many in the human enhancement survey shared this concern, saying that moving forward with the three emerging technologies outlined in the survey – brain implants, synthetic blood and gene editing for babies – would increase inequality because they would only be available to those who are well-off.

Two-thirds of American adults also said scientists would offer life extension technologies before their impact was fully understood. Again, this wariness is matched and even exceeded in the human enhancement survey; more than seven-in-ten adults said brain, blood and gene enhancements would be employed before their effects were fully understood.

Even though the two surveys were conducted separately, they are thematically linked, since research efforts to dramatically extend human life and to “enhance” human beings are occurring in tandem and sometimes together. In fact, the line between the two areas often is blurred. Many scientists and advocates who want to make people stronger and smarter also want to make them healthier and longer-lived, and those who are working to increase longevity and limit the effects of aging in human beings often want to enhance their capabilities as well.

One interesting difference between our polling work on life extension and on human enhancement involves the factors that are contributing to these views. It turns out that religion plays a more prominent role in driving people’s concerns about human enhancement than life extension. For instance, among highly religious people (based on an index of common measures), only 24% say they would want cognitive enhancement, compared with 44% of those with low levels of religious commitment. A similar gap exists when these two groups are asked about gene editing and synthetic blood.

The life extension survey does not use the same religious commitment index. However, among people who attend worship services weekly or more, 33% said they would want treatments to extend their lives, similar to the 36% of those who seldom or never attend church and say the same.