The number of Cubans entering the U.S. has spiked dramatically since President Barack Obama announced a renewal of ties with the island nation in late 2014, a Pew Research Center analysis of government data shows. The U.S. has since opened an embassy in Havana, a move supported by a large majority of Americans, and public support is growing for ending the trade embargo with Cuba.

On Thursday, the White House announced its latest step in policy toward Cuba by ending a long-standing policy that treated Cubans seeking to enter the U.S. differently from other immigrants. Under the old policy, Cubans hoping to legally live in the U.S. needed only to show up at a port of entry and pass an inspection, which included a check of criminal and immigration history in the U.S. After a year in the country, they were allowed to apply for legal permanent residence. The new policy makes Cubans who attempt to enter the U.S. without a visa subject to removal, whether they arrive by sea or port of entry.

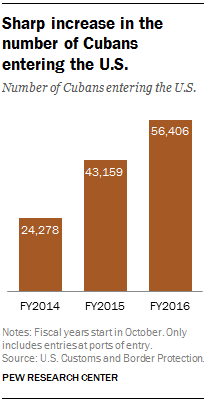

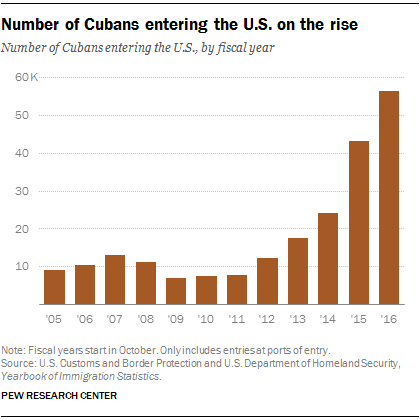

Overall, 56,406 Cubans entered the U.S. via ports of entry in fiscal year 2016, up 31% from fiscal 2015 when 43,159 Cubans entered the same way, according to the latest U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. Fiscal 2015 saw an even larger surge, as Cuban entries jumped 78% over 2014, when 24,278 Cubans entered the U.S. And those 2014 numbers had already increased dramatically from previous years after the Cuban government lifted travel restrictions that year.

The recent rise in the number of Cubans entering the country began in the months immediately following Obama’s December 2014 announcement that the U.S. would renew ties with Cuba. From January to March 2015, 9,900 Cubans entered the U.S. via a port of entry, more than double the 4,746 who arrived during the same time period in 2014. The increase continued into fiscal 2016 and peaked in the first quarter of that fiscal year (October to December 2015), when 17,057 Cubans entered the U.S. via a port of entry, an increase of 85% compared with the same quarter of fiscal 2015.

Thousands of Cubans have migrated to the U.S. by land. Many fly to Ecuador because of the country’s liberal immigration policies, then travel north through Central America and Mexico. However, as some Central American countries have closed their borders to the flow, this route has grown more difficult to travel, and a number of Cuban immigrants have been stranded on their way to the U.S.

The majority of Cubans who have entered the United States by land in recent years arrived through the U.S. Border Patrol’s Laredo Sector in Texas, which borders Mexico. In fiscal 2015, two-thirds (28,371) of all Cubans entering the U.S. came through this sector, an 82% increase from the previous fiscal year. In fiscal 2016, the Laredo Sector continued to receive the majority (64%) of Cuban migrants entering the U.S. through a port of entry. Fiscal 2016 also saw a major spike in El Paso, where 5,179 Cubans entered, up from only 698 Cubans in fiscal 2015.

Since 2014, a large percentage increase has also occurred in the Miami sector, which covers several states but is primarily in Florida. The number of Cubans who entered in the Miami sector during fiscal 2015 more than doubled from the previous year, from 4,709 to 9,999, and this number rose again (to 10,992) in fiscal 2016.

Not all Cubans who attempted to enter the U.S. made it. Under previous U.S. policy, Cubans caught trying to reach the U.S. by sea were returned to Cuba or, if they cited fear of prosecution, to a third country. In fiscal 2016, the U.S. Coast Guard apprehended 5,263 Cubans at sea, the highest number of any country. The total exceeds the 3,505 Cubans apprehended in fiscal 2015.

There are 2 million Hispanics of Cuban ancestry living in the U.S. today, the fourth largest Hispanic origin group behind Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and Salvadorans. But population growth for this group is now being driven by Cuban Americans born in the U.S. The share of foreign born among Cubans in the U.S. declined from 68% in 2000 to 57% as of 2015.

Note: This is an updated version of a post originally published on Oct. 7, 2015.