The former Yugoslavia spent much of the 1990s in turmoil, with a series of wars taking place amid the country’s breakup into its present-day states – each of which has a distinct ethnic and religious makeup.

But a new Pew Research Center survey conducted in the three largest former Yugoslav republics finds that, in general, most people in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia seem willing to share their societies with ethnic and religious groups different from their own – quite a change from the situation during the Yugoslav Wars. At the same time, some underlying signs of tension and distrust linger.

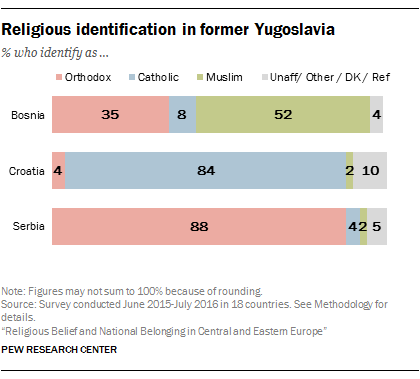

The survey, conducted as part of a broader study of religion in Central and Eastern Europe, finds that Bosnia, the smallest of the three countries in population and in size, is also the most religiously diverse, with roughly half of adults identifying as Muslim and about one-third as Orthodox Christian. Croatia and Serbia each have a single dominant religion: More than eight-in-ten adults identify as Catholic and Orthodox, respectively.

While religious affiliations differ by country, large majorities in all three say a multicultural society is better than a religiously and ethnically homogeneous one. Nearly three-quarters of adults in Bosnia (73%) and about two-thirds in Serbia (66%) and Croatia (65%) agree that “it is better for us if society consists of people from different nationalities, religions and cultures.” Of the 18 countries surveyed in the region, these are the three where this view is most widespread; in several other countries, the prevailing opinion is that it is better for society if there is less religious and ethnic diversity.

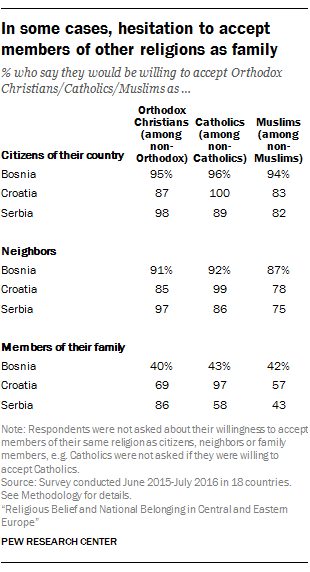

The survey also asked about feelings toward specific religious groups, finding broad acceptance of Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Muslims as fellow citizens and neighbors in the three countries. Respondents were asked if they would be willing to accept people not of their own faith in a few different circumstances, and across each country, at least three-quarters say they would accept members of other religions as neighbors. Even higher shares would be willing to accept them as fellow citizens. For example, 75% of non-Muslims in Serbia say they would accept Muslims as neighbors, while 82% say they would accept them as citizens of their country.

But there are limits to this acceptance: People in all three countries show significantly less willingness to accept followers of other religions as family members. This is most pronounced in Bosnia, despite the fact that it has the most religiously diverse population and the highest percentage in favor of a multicultural society.

Only about four-in-ten non-Muslim Bosnians say they would accept Muslims into their family, similar to the shares of non-Orthodox or non-Catholic Bosnians who say the same about members of those groups. Similarly, in Serbia, only 43% of non-Muslims say they would be welcoming toward Muslims joining the family.

On the other hand, in Catholic-majority Croatia and Orthodox-majority Serbia, even those who are not part of the majority religion (including many who are religiously unaffiliated) are overwhelmingly willing to accept those who do identify with the majority faith as family members.

Across all three countries, adults who have less than a secondary education are, in many cases, significantly less likely than college-educated adults to be willing to accept those from other religious groups as family members. There are no significant differences between men and women or across age groups on these questions, but there is a religious divide: On balance, those who consider religion to be “very important” in their lives are less likely to accept members of other religions into their families.

This reticence is not the only sign of tension in the region. Indeed, more than eight-in-ten adults in all three countries say, in response to a general question about social trust, that “you can’t be too careful in dealing with people” – among the highest shares expressing this view in the broader region of Central and Eastern Europe. Public trust is lowest in Bosnia, where only 6% say that “most people can be trusted.”

In addition, there are still signs of robust nationalism in some of these countries. A majority of Serbians (59%) say it is very important to be Orthodox Christian in order to be “truly Serbian.” And most Bosnians (68%) and Serbians (65%) agree with the statement, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others.”