Globally in 2016, people living abroad sent an estimated $574 billion back to their home countries. Such remittances can be important economic resources, especially to developing countries: Remittance flows into these nations are more than three times that of official development aid, according to a 2016 World Bank report. They also tend to be more stable than other kinds of external capital flows, such as private investment or development aid.

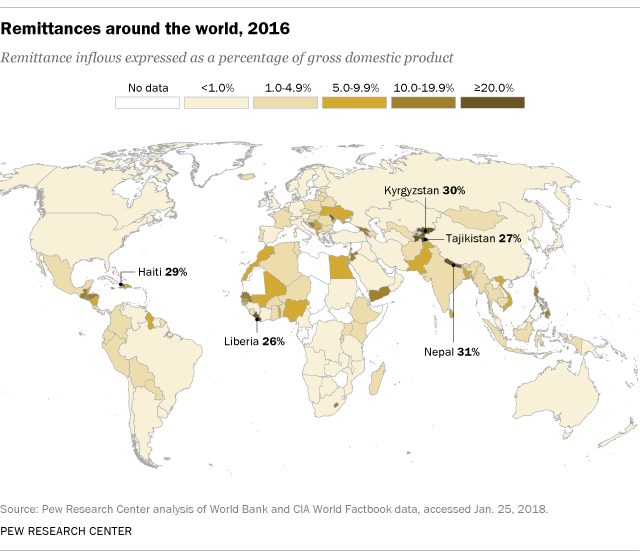

For five countries, in fact, remittances from citizens abroad are equivalent to a quarter or more of all economic output (as measured by gross domestic product, or GDP). Nepal received an estimated $6.6 billion in remittances, equivalent to 31.3% of its GDP, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of World Bank data for 2016. Kyrgyzstan, also in Central Asia, received nearly $2 billion in remittances, equivalent to 30.4% of GDP; neighboring Tajikistan received about $1.9 billion (equal to 26.9% of GDP). Remittances from abroad also equaled more than a quarter of GDP for Haiti and Liberia; in nine other countries they were equivalent to between 15% and 25% of GDP.

View our updated interactive to see the estimated inflows and outflows of money sent by migrants around the world in 2016.

The significance of remittances to a country’s overall economy depends not just on the amount of the remittances, but the size of the economy. According to the World Bank estimates, India received the most remittances in 2016 by sheer dollar amount: $62.7 billion, just ahead of the $61 billion received by second-place China. But those billions – most of which came from Indians working in the United States or the Arabian Peninsula – were equal to just 2.8% of GDP, making them a just a drop in India’s $2.3 trillion economic bucket.

The countries for which remittances are most economically significant generally share two traits: relatively small economies and relatively large diasporas. Nepal’s GDP in 2016 was just $21.1 billion, ranking it 96th in the world by purchasing power parity. Meanwhile, more than 1.6 million Nepalese were living in other countries in 2015, according to a Pew Research Center analysis. The biggest source countries of remittances to Nepal in 2016 were Qatar, Saudi Arabia, India and the United Arab Emirates.

The sheer size of remittance flows means that one country’s immigration policies can have significant effects on other, more remittance-reliant countries. For instance, the Trump administration recently announced that nearly 200,000 people from El Salvador – who have been allowed to live in the U.S. under the Temporary Protected Status program since the small Central American country was hit by a pair of major earthquakes in 2001 – will have to leave by September 2019. The decision could impact El Salvador’s economy, given that remittances from Salvadorans abroad in 2016 were equivalent to 17.1% of the country’s GDP. More than 90% of the $4.6 billion the country received in remittances came from the estimated 1.42 million Salvadoran immigrants living in the U.S.

Studies have shown that remittances can reduce the depth and severity of poverty in developing countries, and that they’re associated with increased household spending on health, education and small business. However, there’s little evidence that they have much impact on overall economic growth in receiving countries.

Researchers have suggested several explanations for this seeming paradox, including that much of the apparent increase in remittances in recent decades may be an artifact of improved measurement methods rather than more actual cash; that economic data and modeling techniques may be inadequate to detect any growth effects; and that remittances from migrants may be partially offset by the depressing effect those migrants’ absence has on their home country’s economy.