Most Christians in Western Europe today are non-practicing, but Christian identity still remains a meaningful religious, social and cultural marker, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of 15 countries in Western Europe. In addition to religious beliefs and practices, the survey explores respondents’ views on immigration, national identity and pluralism, and how religion is intertwined with attitudes on these issues.

Here are 10 key findings from the new survey:

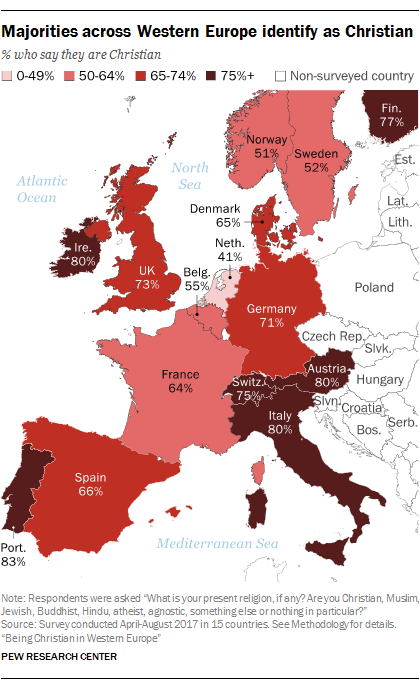

Secularization is widespread in Western Europe, but most people in the region still identify as Christian. Rising shares of adults in Western Europe describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated, and about half or more in several countries say they are neither religious nor spiritual. Still, when asked, “What is your present religion, if any?” and given a list of options, most people identify as Christian, including 71% in Germany and 64% in France.

Even though most people identify as Christian in the region, few regularly attend church. In every country except Italy, non-practicing Christians (that is, those who attend church no more than a few times a year) outnumber church-attending Christians (those who attend church weekly or monthly). In the UK, for example, there are three times as many non-practicing Christians (55%) as practicing Christians (18%). Non-practicing Christians also outnumber religiously unaffiliated adults in most countries surveyed.

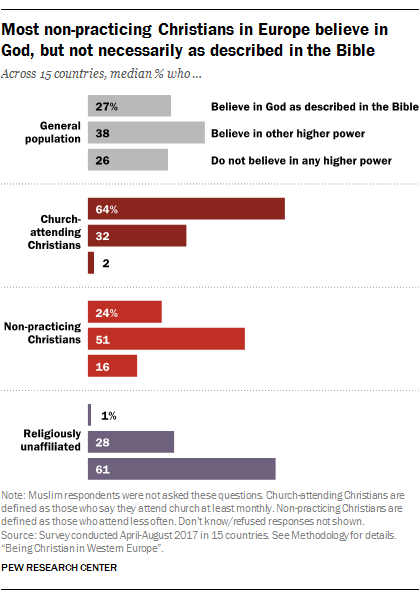

Christians in Western Europe, including non-practicing Christians, believe in a higher power. Although many non-practicing Christians say they do not believe in God “as described in the Bible,” they do tend to believe in some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe. By contrast, most church-attending Christians say they believe in God as depicted in the Bible. And religiously unaffiliated adults generally say they do not believe in God or any higher power or spiritual force in the universe. Non-practicing Christians are also more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to embrace spiritual concepts such as having a soul and feeling a connection to something that cannot be measured.

Majorities in most countries across the region say they would be willing to accept Muslims in their families and in their neighborhoods. Still, undercurrents of discomfort with multiculturalism are evident in Western European societies. People hold mixed views on whether Islam is compatible with their national values and culture, and most favor at least some restrictions on the religious clothing worn by Muslim women. In addition, roughly half or more in most countries in the region say it is important to have been born and have ancestry in a country to truly share its national identity. For example, roughly half of Finnish adults say it is important to be born in Finland (51%) and to have Finnish family background (51%) to be truly Finnish.

Christian identity in Western Europe is associated with higher levels of nationalism and negative sentiment toward immigrants and religious minorities. Across the region, Christians, church-attending or not, are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to say “Islam is fundamentally incompatible with our country’s values and culture.” In Germany, as in several other countries, overall public opinion is split on whether Islam is compatible with German values and culture, with 55% of churchgoing Christians saying Islam is incompatible with German values and culture, compared with 45% among non-practicing Christians and 32% among religiously unaffiliated adults. Similarly, both practicing and non-practicing Christians are more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to say their culture is superior to others, and to favor reducing immigration from its current levels.

Aside from religious identity, other factors – such as education, political ideology and personal familiarity with Muslims – are associated with levels of nationalist, anti-immigrant and anti-religious minority sentiment. Western Europeans who have a college education are less likely than others to say they would not accept Jews or Muslims in their family, or to say their culture is superior to others. And people who say they personally know someone who is Muslim also are less likely to express these kinds of sentiments. Conversely, Western Europeans on the right of the ideological spectrum are more likely than those on the left to say they would be unwilling to accept Jews or Muslims in their family, or that it is important to have been born in their country to truly belong.

In Europe today, attitudes toward Jews and attitudes toward Muslims are highly correlated with one another. Although current debates on multiculturalism in Europe largely focus on Islam and Muslims, people who say they would be unwilling to accept Muslims in their family are also more likely than others to say they would be unwilling to accept Jewish people in their family. And those who agree with the statement, “In their hearts, Muslims want to impose religious law on everyone else in our country,” are also more likely to agree with the statement, “Jews always pursue their own interests and not the interests of the country they live in.” The survey also finds familiar patterns by religious identity when it comes to views about Jewish people: Although most Christians overall say they would be willing to accept Jews in their families, Christians are somewhat more likely than religiously unaffiliated adults to express negative sentiments toward Jews.

Majorities across the region, including most Christians, favor legal same-sex marriage and abortion. Similar to religiously unaffiliated adults, the vast majority of non-practicing Christians say gay and lesbian couples should be allowed to legally marry, and that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Churchgoing Christians are less likely to take these positions, but even among religious Christians, majorities favor gay marriage and legal abortion in Belgium, Denmark, France, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK.

The prevailing view in Western Europe is that religion should be kept separate from government policies. In Sweden, for example, 80% of respondents favor separation of religion and government, as do 72% in Belgium. Still, substantial minorities in several countries, including 38% in the UK and 45% in Switzerland, say government policies should support religious values and beliefs in the country, a position much more popular among churchgoing Christians than among non-practicing Christians. Religiously unaffiliated adults are less likely than Christians at all levels of practice to support church-state ties.

The share of religiously unaffiliated adults in several Western European countries is comparable to the share of religiously unaffiliated adults in the U.S., but American “nones” are more religious than their European counterparts. About a quarter of Americans (23% as of 2014) say they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” similar to the shares of religiously unaffiliated adults in the UK (23%) and Germany (24%). But while secularization is evident on both sides of the Atlantic, unaffiliated Americans are much more likely than their counterparts in Europe to pray and to believe in God, just as U.S. Christians are considerably more religious than Christians across Western Europe. In fact, by some of these standard measures of religious commitment, American “nones” are as religious as – or even more religious than – Christians in several European countries, including France, Germany and the UK.