Populist movements have gained ground in many Western European countries, from the United Kingdom’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union to Italy’s formation of a populist government this spring. A new Pew Research Center report explores the attitudes that underlie some of these movements, based on interviews with more than 16,000 adults in eight Western European nations.

In the surveyed countries – Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the UK – people with populist views (as measured by two questions on anti-establishment attitudes) are more likely than those with mainstream views to distrust traditional institutions, such as the national parliament and the news media. They are also more likely to be frustrated with the economy and to hold negative views toward immigrants. Still, populist sympathies play less of a role in many aspects of European politics than traditional left-right divides do. People in Western Europe, for example, still tend to back political parties that reflect their own ideological preferences.

Below are five key takeaways from the survey:

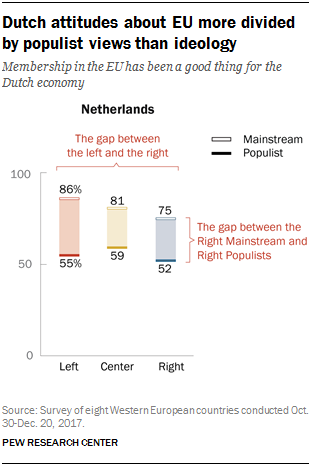

Populist attitudes are not confined to one particular end of the ideological spectrum in Western Europe – they exist on the left, center and right. In some cases, populist views are a more significant dividing line on political issues than ideology is. For example, Dutch adults with populist views are less likely than those with mainstream views to say membership in the EU has been good for their country’s economy – and this difference exists whether respondents are on the ideological left, center or right. (For the specific definitions of populist views and ideology used in this study, read our methodology.)

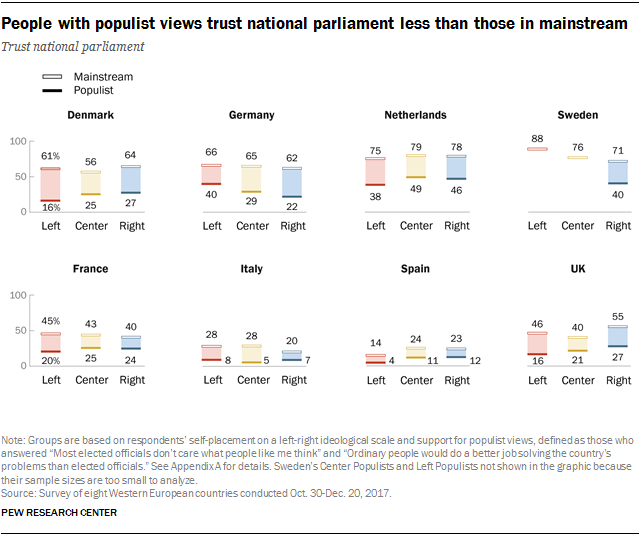

People with populist views are generally much more dissatisfied with traditional institutions than people with mainstream views. This is true for all four institutions the survey asked about: the national parliament, the news media, banks and financial institutions and, to a lesser degree, the military. Again, this often holds regardless of respondents’ positions on the ideological spectrum. In Denmark, for instance, only 16% of populists on the ideological left say they trust the national parliament, compared with 61% of Danes with mainstream left views. Similarly, only 27% of Danish populists on the ideological right say they trust parliament, compared with 64% of Danes with mainstream right views.

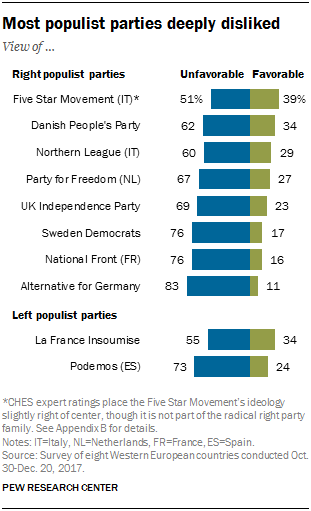

While populist attitudes span the ideological spectrum, populist political parties are relatively unpopular in Western Europe. Across the surveyed countries, around four-in-ten adults or fewer have a favorable view of the populist party (or parties) in their nation. For example, only 34% of people in Denmark have a favorable view of the Danish People’s Party; 23% of people in the UK view the UK Independence Party favorably; and 16% of French adults see the National Front favorably. Traditional parties do much better than populist parties in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden. But they face difficulties elsewhere: For most of the traditional parties the survey asked about, three-in-ten or fewer of respondents in France, Italy and Spain have a favorable view. In all eight surveyed countries, attitudes about both types of parties – traditional and populist – are heavily colored by respondents’ ideological views.

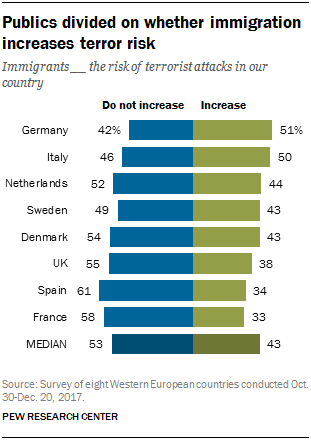

Western Europeans are divided over the impact of immigration on their nation’s culture, security and economy, particularly along ideological lines. For example, a third or more in each country surveyed say immigrants increase the risk of terrorism in their nation, with Germans and Italians the most likely to express this view. Within each country, left-right ideology tends to influence these opinions more than populist views do. People on the right are at least 20 percentage points more likely than those on the left to say immigrants increase the risk of terrorism in their country. Still, in most countries, populist views also matter – the populist groups studied tend to be more negative toward immigrants on the security issue than their mainstream counterparts are.

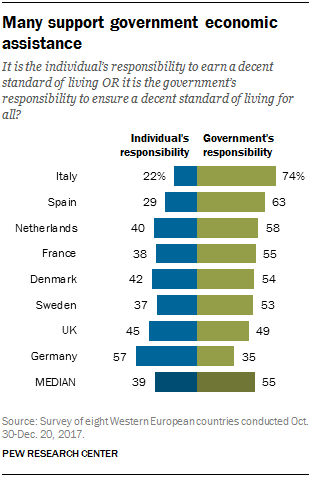

Traditional left-right divisions play a bigger role than populist attitudes when it comes to views of the government’s role in ensuring a decent standard of living. In general, Western Europeans tend to say it is the government’s responsibility to ensure a decent standard of living for all: A median of 55% across the eight countries surveyed hold this view (though Germany is a notable exception). Left-right ideology is central to how people feel about this issue. Most of those on the political left place the responsibility on the government to guarantee that everyone has a decent standard of living, while many on the right say it is up to the individual. There tend to be smaller differences on this question between those with populist views and those with mainstream attitudes.