Automation already plays a significant role in the U.S. workplace, and most Americans expect technological advances to continue to alter the job landscape in the decades ahead. These seven charts, based on recent Pew Research Center surveys, highlight Americans’ views toward job automation:

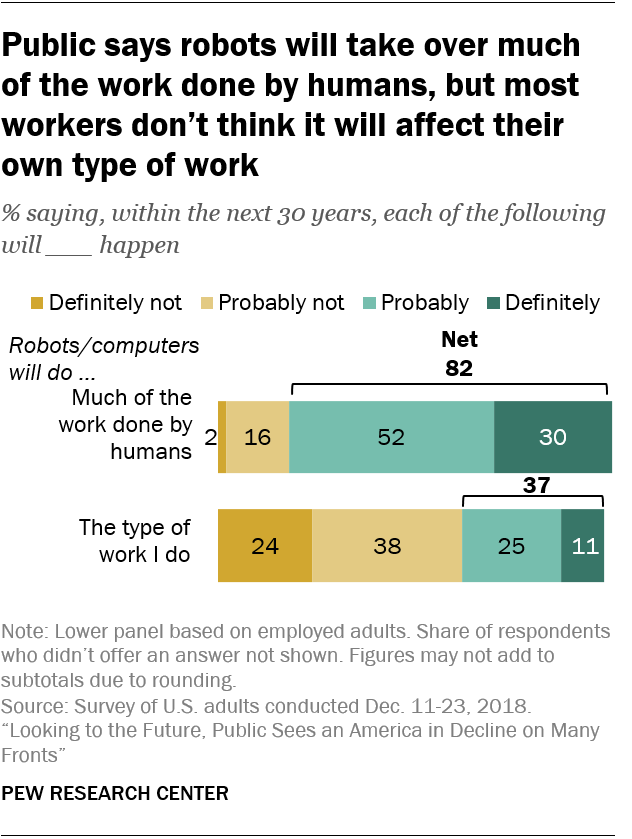

Most Americans anticipate widespread job automation in the coming decades. About eight-in-ten U.S. adults (82%) say that by 2050, robots and computers will definitely or probably do much of the work currently done by humans, according to a December 2018 Pew Research Center survey. A smaller share of employed adults (37%) say robots or computers will do the type of work they do by 2050.

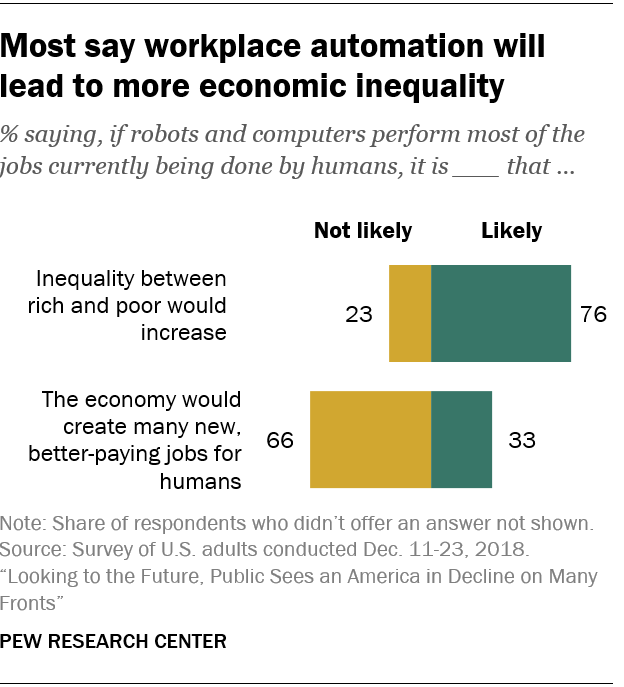

The U.S. public generally anticipates more negative than positive effects from widespread job automation. Around three-quarters of Americans (76%) say inequality between the rich and the poor would increase if robots and computers perform most of the jobs currently being done by humans by 2050. Only a third (33%) believe it’s likely that this kind of widespread automation would create many new, better-paying jobs for humans.

In a May 2017 Pew Research Center survey, around four-in-ten U.S. adults said an automated future would make the economy more efficient, let people focus on the most fulfilling aspects of their jobs or allow them to focus less on work and more on what really matters to them in life. In each instance, a majority of the public said these positive outcomes are unlikely.

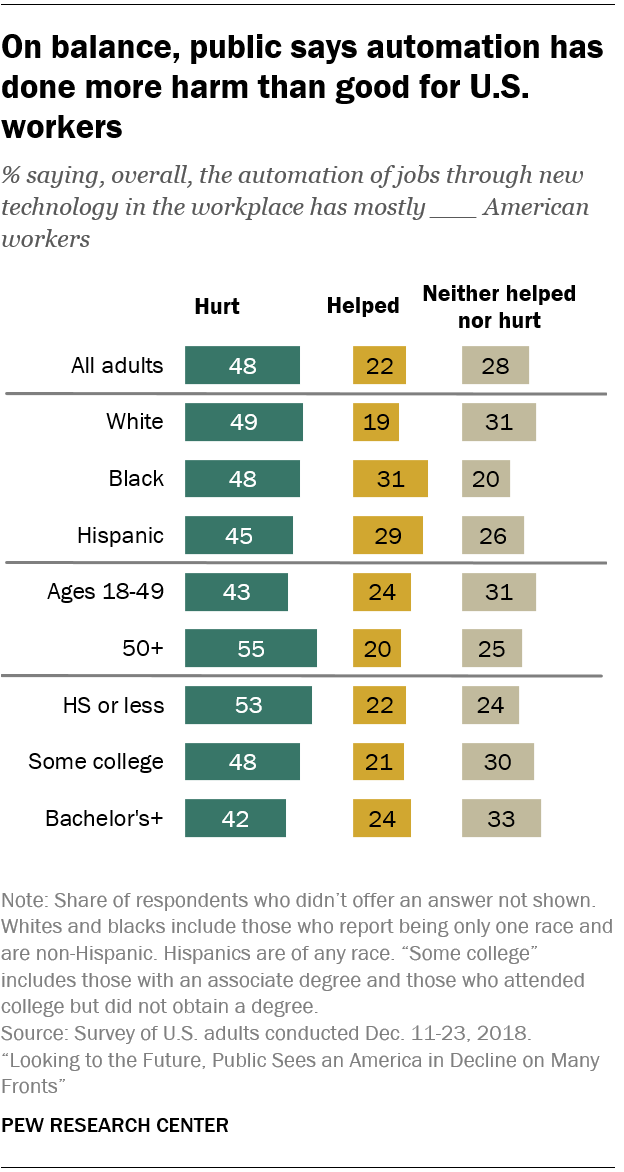

When it comes to workplace automation that has already occurred, Americans are more likely to say it has hurt U.S. workers than helped them. Around half of U.S. adults (48%) say job automation through new technology in the workplace has mostly hurt American workers, while just 22% say it has generally helped, according to the 2018 survey. About three-in-ten (28%) say these advances have neither helped nor hurt U.S. workers.

Adults 50 and older are more likely than younger Americans to say job automation has hurt workers (55% vs. 43%), as are adults with a high school diploma or less when compared with those with a bachelor’s degree or more (53% vs. 42%).

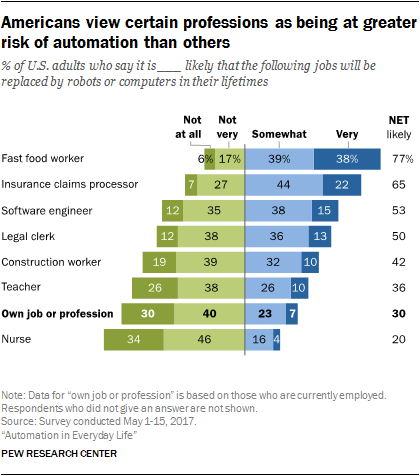

Americans think automation will likely disrupt a number of professions – but they are less likely to foresee an impact on their own jobs. In the Center’s 2017 survey, around three-quarters of U.S. adults (77%) said it was very or somewhat likely that fast food workers would be replaced by robots or computers in their lifetimes, while about two-thirds (65%) said the same about insurance claims processors. Around half said automation would replace the jobs of software engineers and legal clerks, while smaller shares said it would affect construction workers, teachers or nurses. Three-in-ten Americans said their own jobs would become automated in their lifetimes. (A slightly different question was asked in the 2018 survey.)

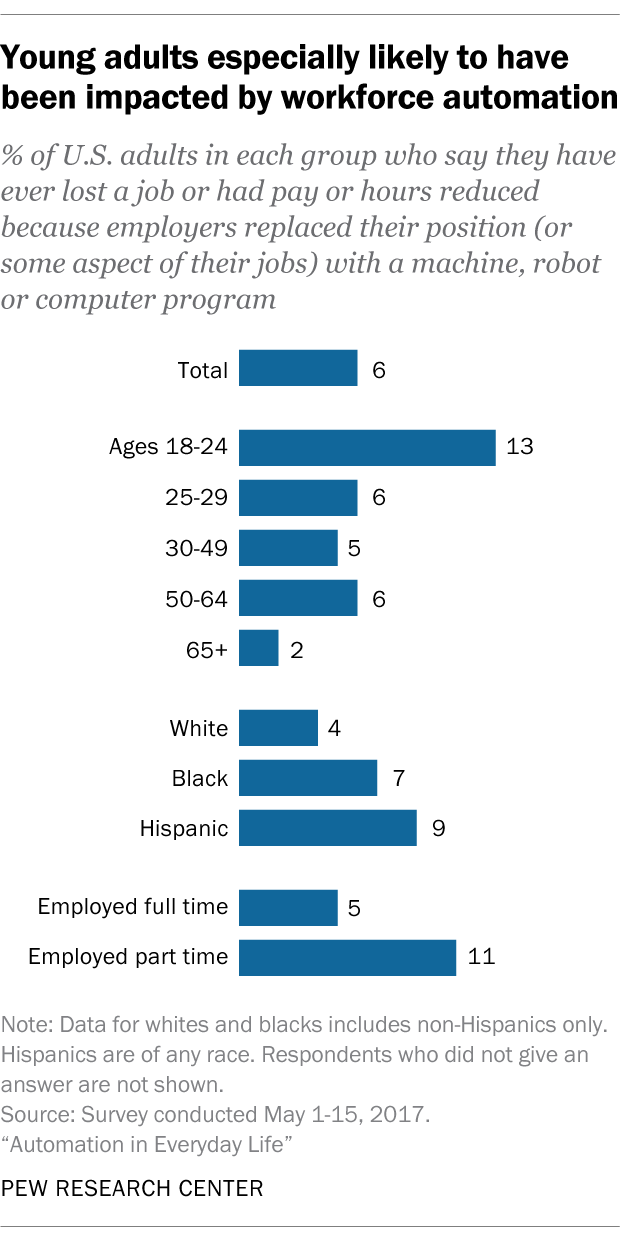

Young adults and part-time workers are especially likely to have been personally affected by workforce automation. In 2017, 13% of those ages 18 to 24 had either lost a job or had pay or hours reduced because their employers replaced their positions with a machine, robot or computer program. That compares with slightly smaller shares of those ages 30 and older. Those employed part time were also slightly more likely than those employed full time (11% vs. 5%) to cite these personal impacts from automation.

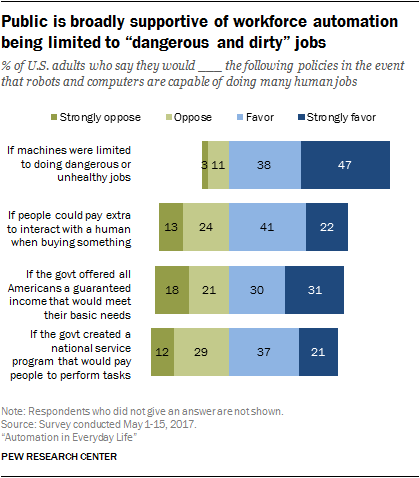

Many Americans say there should be limits on job automation – and majorities support certain policies aimed at doing so. Nearly six-in-ten Americans said in 2017 that there should be limits on the number of jobs that businesses can replace with machines, even if those machines are better and cheaper.

Most Americans also expressed support for policies aimed at limiting automation to certain jobs or cushioning its economic impact. A large majority (85%) said they would support restricting workforce automation to jobs that are dangerous or unhealthy for humans to do. Six-in-ten said they would favor a federal policy that would provide a guaranteed income for all citizens to meet basic needs in the instance of widespread job automation, and a similar share (58%) said they would support a federal program that would pay people to do tasks even if machines are able to do the work faster and more cheaply.

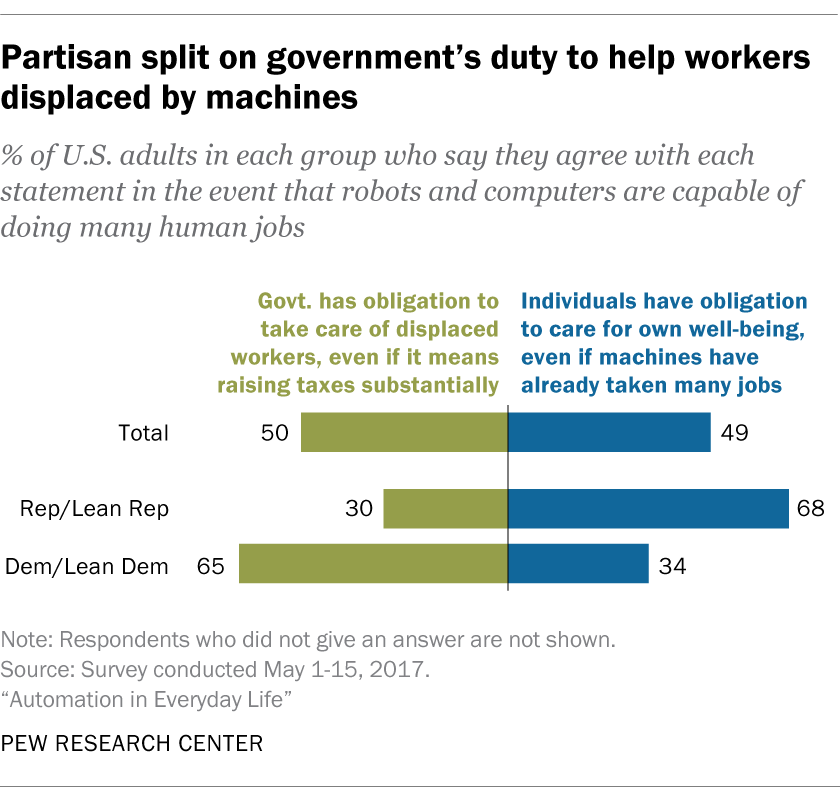

Americans are divided over whose responsibility it is to take care of displaced workers in the event of far-reaching job automation. Half of U.S. adults said that in the event that robots and computers are capable of doing many human jobs, it is the government’s obligation to take care of displaced workers, even if it means raising taxes substantially, according to the 2017 survey. A nearly identical share (49%) said that obligation should fall on the individual, even if machines have already taken many human jobs.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents were far more likely than Republicans and GOP leaners (65% vs. 34%) to say the government is obligated to help displaced workers in the event that robots become capable of doing many human jobs, while Republicans were much more likely to say individuals should be responsible (68% vs. 30% of Democrats).