Editorial note to readers (March 19, 2025):

This project estimated the number of unauthorized immigrants living in 32 European countries during the mid- to late-2010s. We used what were then the best available data sources from different governments and from the European Union. After our report was published in November 2019, researchers at the University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory identified a problem with the official data from the United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) on the number of legal immigrants residing in the UK.

The ONS data on legal immigrants that we used in our report did not include those with “indefinite leave to remain” (ILR), a group legally residing in the country. Including the ILR group among legal UK residents results in lower estimated total numbers of unauthorized immigrants for both the United Kingdom and Europe in 2017 and other years. The updated estimates for the number of unauthorized immigrants in 2017 (without waiting asylum seekers) are 700,000-900,000 for the UK and 2.8 million-3.5 million for Europe. Updated estimates can be found in this table but are not reflected elsewhere in this short read.

Learn more

Full report: Europe’s Unauthorized Immigrant Population Peaks in 2016, Then Levels Off

How European and U.S. unauthorized immigrant populations compare

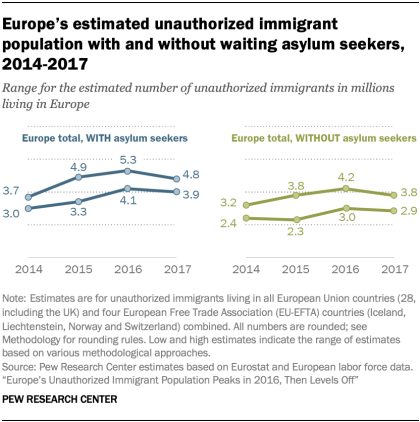

Europe is one of the world’s top destinations for immigrants, and in recent years it has seen new waves of people arrive on its shores seeking asylum. The number of unauthorized immigrants living in Europe has grown, though it has leveled off more recently. In 2017, 3.9 million to 4.8 million unauthorized immigrants lived in Europe, according to new Pew Research Center estimates.

Senior Researcher Phillip Connor and Senior Demographer Jeffrey S. Passel developed the Center’s estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population in Europe. In this Q&A, they explain the variety of methods and data sources they used, as well as the challenges they faced. You can also watch the video above for a summary of how they arrived at their estimates.

Who is defined as an unauthorized immigrant in your new study of Europe?

Senior Demographer

Pew Research Center

Passel: In general, unauthorized immigrants in Europe are defined as those who are not citizens of a European country and do not have valid residency permits. Some entered their country of residence without authorization, while others became unauthorized immigrants after entering on a visa and staying past its expiration date. Our estimates include some people who have temporary permission to stay in a country but face an uncertain legal future – for example, those whose deportation has been deferred. We also included individuals who applied for asylum but are still waiting for a final decision on their application. (Note: In the Center’s new study, Europe includes countries in the European Union, including the United Kingdom, and the European Free Trade Association countries of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.)

Are unauthorized immigrants the same as illegal or irregular immigrants?

Senior Researcher

Pew Research Center

Connor: No. There is no universal definition for any of these terms. The inclusion of some groups over others in an unauthorized immigrant population estimate is a point of debate. Under our definition, some immigrants who are legally in their countries of residence, such as those waiting on an asylum case and those who have had their deportation deferred, are included as unauthorized immigrants. In deciding which groups of immigrants to include or not include in this population, we’ve considered factors such as how people entered the country and the uncertainty of their future legal status. We’ve used the term “unauthorized immigrant” for many years to describe this population in the United States. In a European context, the unauthorized immigrant population generally consists of the same groups of immigrants as in the U.S.

Why did you include waiting asylum seekers in your unauthorized immigrant estimates?

Connor: In the case of asylum seekers waiting for a decision on their cases, we included them in our estimate because many entered Europe without permission during the most recent asylum seeker surge. It’s also worth noting that rejection rates on asylum cases are high in many European countries, though this wasn’t a primary factor in our decision to include this group in our estimates. We take a similar approach to our estimates in the U.S.

Some do not consider asylum seekers to be unauthorized immigrants because they have a legal right to live in Europe while they wait for a decision on their asylum application. So we also prepared unauthorized immigrant estimates without the roughly 1 million asylum seekers awaiting a decision. Even without this group in the total, we found an apparent increase in the unauthorized immigrant population from before the asylum seeker surge – from a range of 2.4 million to 3.2 million in 2014 to a range of 2.9 million to 3.8 million in 2017.

How did you estimate the number of unauthorized immigrants living in Europe?

Connor: Developing an estimate of the number of immigrants living in a country without authorization is difficult because many in this population prefer to remain hidden. To produce estimates of unauthorized immigrants in each country, and for Europe as a whole, required a thorough assessment of the data available. Depending on the comprehensiveness, recency and completeness of verifiable data sources for each country, we used one of four estimation methods.

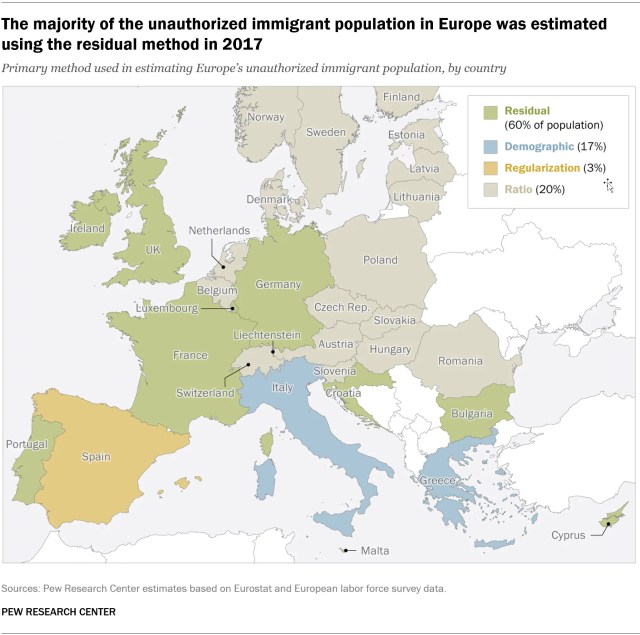

The first is referred to as the residual method, which we have successfully used in the United States for more than a decade. In terms of mechanics, the residual method is straightforward: We first determine the total number of noncitizens living in a particular country – in this case, residents who are not citizens of an EU or European Free Trade Association country – and then subtract the number of noncitizens who are authorized to be there. The remainder is the estimate of unauthorized immigrants. We used this technique for 11 countries that were home to 60% of unauthorized immigrants in Europe in 2017.

Estimates of the total number of noncitizens usually come from a national survey (such as a census), a population register (a government database of current residents) or a combination of sources. Since we know not all unauthorized immigrants are included in these data sources, we adjust our estimates in some countries to account for those omitted from the census or population register based on factors like survey quality and previous estimates from other researchers. These slight upward adjustments are consistent with what we do in the United States and have been used previously in the UK.

We used other methods in countries that did not have the data needed for the residual method. In Italy and Greece, we used a second method known as the demographic components method. We started with estimates from 2008, the most recent available. We then updated them by adding information on subsequent births, deaths and new migration, including asylum seekers.

In Spain, we used a third approach, the regularization method, to estimate the size of the country’s unauthorized immigrant population. This involved using data from a Spanish government program that provides unauthorized immigrants in Spain the opportunity to acquire regular immigration status. We used data on the number of immigrants who regularized to project the unauthorized population in Spain into later years. This approach provided a minimum number of people who were at one time living in Spain without authorization; we also added asylum seekers with pending applications to this estimate.

For countries where available data would not allow us to use the first three approaches, we used a proportional ratio method. Often the countries in question had smaller immigrant populations. For each of these countries, we identified another country with similar migration patterns for which we already had an estimate of its unauthorized immigrant population. We took that country’s ratio of unauthorized-to-authorized immigrants and applied it to the noncitizen population of the country for which we didn’t have an estimate. In most countries, we then added the number of waiting asylum seekers to the unauthorized immigrant totals.

How did you determine the demographic characteristics of Europe’s unauthorized immigrant population?

Passel: Our report includes demographic characteristics like nationality, time living in a country, age and sex for unauthorized immigrants in Europe and select countries. We found that these immigrants are from a diverse set of countries, have generally been in Europe for a relatively short period of time, are majority male, and are mostly under the age of 35. This is the first time such detailed characteristics for all of Europe have been published. To do this, we employed methods similar to those we have used to determine characteristics of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S.

We used social, economic and household characteristics found in each country’s labor force survey – a government survey carried out in most European countries – to identify individual immigrants who were most likely to be authorized. For example, we know an immigrant in a government job, or one married to a citizen of the country where the immigrant lives, is likely authorized to be in the country. Once we identified the immigrants to likely be authorized, we considered the remaining immigrants in the survey to be potentially unauthorized. We then randomly sampled a portion of this group of potentially unauthorized immigrants, based on the estimated size of the unauthorized immigrant population. This provided us a dataset of likely unauthorized immigrants that included demographic characteristics for each individual.

This approach to identifying unauthorized immigrants and assessing their characteristics can be applied when the underlying survey data is representative of the entire population and can be demonstrated to include unauthorized immigrants. Surveys that use an address-based sample tend to include housing units where unauthorized immigrants reside and are nationally representative. (Surveys based exclusively on population registers are unlikely to include unauthorized immigrants, as this population is generally not part of population registers.)

We used two types of data to determine the characteristics of unauthorized immigrants – national labor force surveys and administrative data on asylum seekers. We know that unauthorized immigrants are included in the national labor force surveys of 18 countries, including the two with the largest unauthorized immigrant populations – Germany and the UK. For these 18 countries, the number of potentially unauthorized immigrants in the survey exceeds our estimate of unauthorized residents. We then added administrative data on asylum seekers waiting for a decision on their cases from all 32 European countries. Together, this permitted us to provide demographic characteristics for 84% of Europe’s estimated unauthorized immigrant population in 2017. One of the largest groups not included is unauthorized immigrants in Italy who do not have a pending asylum claim.

What were the challenges of producing these estimates?

Connor: The Center has 15 years of experience in estimating the size of the unauthorized immigrant population in the U.S., but this is the first time we have estimated the size of this population in Europe. Developing estimates for Europe presented unique challenges, particularly with data.

Our primary data sources were provided by Eurostat, the European Union’s statistical agency. Since data collection practices vary from one nation to the next, we had to determine the best method to use in each country, given the available data. For example, some of the data on noncitizens is based on censuses and surveys while others are based on population registers. Also, some include asylum seekers with pending applications and others do not. Meanwhile, data on unauthorized immigrants may be included in censuses and surveys, but not population registers. To determine the best method, we consulted with data experts, compared various data sources and tried multiple approaches to estimating the unauthorized immigrant population. We also turned to other data sources when Eurostat data didn’t allow us to use our estimation methods.

Why do your estimates only go back to 2014? And why end at 2017?

Connor: The Eurostat data sources we used to estimate the unauthorized immigrant population are available back to 2014. Data from the end of 2017 was the most recent available. Also, it’s common for estimates like these to lag a year or two because it takes time for population data to become available and for researchers to analyze the data to prepare estimates.

Note: For a more detailed explanation of how we estimated the unauthorized immigrant population in Europe, read the report methodology.