The decennial redistricting process, in which states use fresh population data from the U.S. Census Bureau to draw new congressional and state legislative district lines, would normally have been well underway by now. But pandemic-related delays at the Census Bureau in collecting and analyzing the 2020 census data have left the process months behind schedule. That could create political turmoil at the state level – particularly in Virginia and New Jersey, which hold state elections this year.

The once-a-decade redrawing of congressional and state legislative districts tends to be a contentious process even in the best of times. We conducted this analysis to examine today’s partisan environment at the state level and how it compares with redistricting seasons past.

We decided to focus on congressional, rather than state legislative, redistricting. As used in this analysis, reapportionment refers to the process of distributing the 435 House seats among the states after every census. Redistricting refers to the redrawing of district lines within a state to reflect population shifts and, if necessary, gains or losses in the number of House seats.)

For the purposes of this analysis, a party is considered to drive the redistricting process in a state if it controls both houses of the legislature and also holds the governor’s office; or, if the governor is of a different party, either he or she cannot veto a legislatively approved plan or the party has a legislative supermajority and can override the governor’s veto.

For current party standings in state legislatures, we relied on individual legislative websites, most of which list lawmakers by party affiliation. In a handful of cases, we supplemented those sources with data from Ballotpedia and local media outlets – most notably in the case of Nebraska’s unicameral and officially nonpartisan legislature and Alaska’s House of Representatives. (Despite having more Republicans than Democrats, the Alaska House is run by a “coalition caucus” of 14 Democrats, two Republicans and four independents.) State websites gave us the party affiliations of governors.

Our main source for information on state redistricting procedures was the National Conference of State Legislatures, supplemented by Ballotpedia and the online versions of individual state constitutions. The NCSL also was our main source for information on veto override requirements and the creation of redistricting commissions, again supplemented when necessary by state constitutions.

Our main source for party breakdowns of state legislatures in previous years and decades was “The Book of the States,” compiled by the Council of State Governments. Numbers in some cases reflect a prior or subsequent year based on what data was available.

Whenever it happens, redistricting is an intensely, and innately, political process. And when the 35 state legislatures that vote on congressional redistricting get the data they need by Sept. 30 to draw new maps, Republicans will drive that process in 20 states, versus 11 for Democrats, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis. In four states with divided governments, the process could be more complicated.

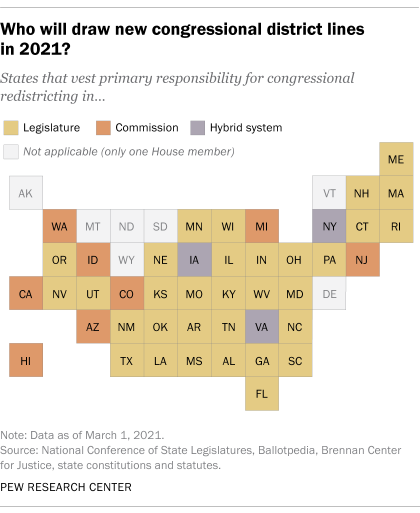

States employ a variety of methods to redraw their congressional districts, the focus of this post. (Some states have different mechanisms for redrawing state legislative districts.) In 32 states, legislatures have the primary responsibility, while eight states give the job to nonpartisan or bipartisan commissions. Three additional states have hybrid systems, in which outside panels draw maps that legislatures can approve or reject but not change. And in seven states, the whole question is moot, at least as far as Congress is concerned, because they have only one representative, elected at-large. (Should Montana gain a seat in the upcoming reapportionment – the process that determines how many representatives each state is allocated – the lines would be drawn by a commission. The reapportionment count is expected by April 30.)

For the purposes of this analysis, a party is considered to drive the redistricting process in a state if it controls both houses of the legislature and also holds the governor’s office; or, if the governor is of a different party, either he or she cannot veto a legislatively approved plan or the party has a legislative supermajority and can override the governor’s veto.

Out of the 35 states in which legislatures vote on congressional redistricting plans, there are 23 in which Republicans have majorities in both legislative chambers. (That figure includes Nebraska, whose unicameral legislature is officially nonpartisan but is commonly acknowledged as having a GOP majority.) In 11 of those 35 states, Democrats control both chambers. Minnesota’s legislature is split between the Democratic-controlled House and the Republican-run Senate.

Of the 23 states with Republican legislative majorities and where the legislature votes on plans, six have Democratic governors. But North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper has no veto over redistricting plans, and Republicans have veto-proof supermajorities in Kansas and Kentucky. That means Republicans effectively dominate the redistricting process in 20 states.

Of the 11 states with Democratic legislative majorities, two (Massachusetts and Maryland) have Republican governors, but in both cases Democrats have veto-proof supermajorities, meaning they can still play the dominant role.

Including Minnesota, four states vest redistricting authority with the legislature and have divided state governments. In Louisiana, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, Republican-run legislatures will have to come to agreement with Democratic governors on new congressional maps.

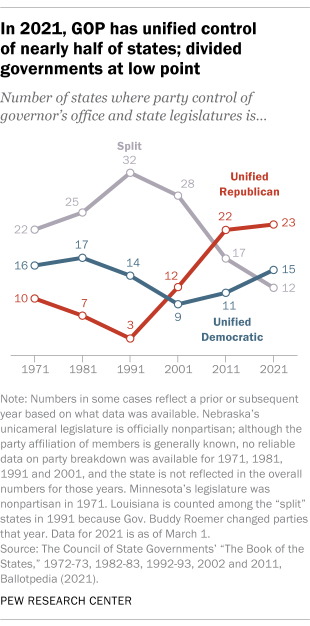

More broadly, divided government is less common at the state level than it used to be. Republicans and Democrats currently share power at the legislative and/or gubernatorial levels in only 12 states overall. Republicans control both the legislature and the governor’s office in 23 states; Democrats do so in 15 states.

By contrast, during the redistricting season that followed the 1970 census, there were at least 22 states with split control. (The exact number is unclear because Minnesota and Nebraska had formally nonpartisan legislatures at the time, and because of how much time has passed, we could not pin down the effective partisan breakdowns.) The peak for split state governments in redistricting years came in 1991-92, when 32 states had some form of power-sharing.

In 1978, Hawaii became the first state to hand authority over congressional redistricting to a bipartisan commission. Washington state did so in 1983, and seven other states (including Montana, whose commission doesn’t handle congressional redistricting as the state has only one district) have followed its lead since then.

This year’s census delays likely will scramble political calendars in several states. Virginia and New Jersey, which will hold legislative (and gubernatorial) elections this fall, almost certainly will have to run them under the existing maps, which don’t reflect recent population shifts that could benefit one party or the other. New Jersey voters last year approved a plan to delay redistricting until the data comes in and implement new maps in 2023. But Virginia may be looking at three straight years of House elections.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 25 other states have constitutional or statutory requirements to redistrict in calendar year 2021 – deadlines that the census delays will make it difficult if not impossible to meet.