After all the dust settled from the 2020 elections, the U.S. Senate was effectively split down the middle for the first time in 20 years – 50 Republicans versus 48 Democrats and two independents who caucus with them. Even though Democrats controlled the Senate thanks to the tiebreaking vote of Vice President Kamala Harris, much of the party’s legislative agenda ran up against the political reality that, for most bills, 60 votes are needed to shut off delaying tactics – known as filibusters – and bring bills to a final vote.

Since January 2021, Democrats have controlled the Senate by the slimmest of margins: A 50-50 split with Republicans (including two independents who caucus with the Democrats) allows Vice President Kamala Harris to break ties. But much of the Democratic agenda has been stymied by Republican filibusters, which require 60 votes to overcome; that’s led many on the party’s left flank to call – so far unsuccessfully – for the filibuster’s abolition.

Given that context, Pew Research Center wanted to examine how cloture – the process of ending a filibuster – works in practice in today’s Senate, and how that’s changed over time.

We relied on two main sources to track cloture use: the Library of Congress’ congress.gov database of legislative information, and the Senate’s own compilation of cloture motions and their outcomes. Using these sources, we identified each bill with a legislative history that included at least one cloture vote, the specific circumstances and outcome of each vote, and whether the bill in question became law. We also compiled similar data on cloture votes tied to presidential nominations.

Filibuster: The general term for any organized effort, by one or more senators, to block a bill, nomination or other measure from coming to a vote. In the past, filibusters typically involved a senator or group of senators holding the floor by speaking for as long as they could; this is now often called a “talking filibuster.” Today, however, senators can filibuster simply by objecting to the Senate moving ahead to a vote – as long as they have 40 or more of their colleagues behind them.

Cloture: The procedure to break a Senate filibuster and move a pending question toward a final vote. For bills, 60 votes are needed to invoke cloture, after which debate generally can last no more than 30 hours. For presidential nominations, a simple majority can invoke cloture, and in most cases only two more hours of debate will be allowed.

Budget reconciliation: An expedited procedure intended to bring tax and spending laws into line with Congress’ budgetary goals (as expressed in the annual budget resolution). Bills being considered under the reconciliation process cannot be filibustered, and debate on them is limited. But the content of such bills is also limited, generally to matters that affect federal revenues, expenditures or borrowing.

Public laws: The vast majority of laws passed by Congress are designated “public laws,” meaning that they affect society as a whole and are binding on all people. “Private laws” typically affect a single person (or at most one family or small group), and usually are passed to resolve some issue between that person and the government, such as settling a claim or resolving an immigration matter.

Substantive vs. ceremonial laws: In a series of analyses of Congress’ legislative productivity that goes back to 2014, Pew Research Center makes a distinction between “substantive laws” and “ceremonial laws.” In general, we define substantive laws as those that have some real-world impact, no matter how small: spending money, setting policy, acquiring or disposing of federal land or even correcting typographical errors in earlier laws. Ceremonial laws are those intended mainly to recognize an individual, group or cause. That can mean naming or renaming courthouses, post offices, veterans’ hospitals and other federal facilities; authorizing commemorative coins or medals; designating special days, weeks or months; or permitting outside groups to erect memorials on federal land.

Many Democratic lawmakers and political activists have called for ending the filibuster entirely and allowing simple majorities to move legislation forward. But even though there haven’t been enough votes to abolish the filibuster, the current Senate has managed to clear the 60-vote hurdle on more than two dozen occasions – including on several of this Congress’ main legislative achievements.

So far in the 117th Congress, 29 separate pieces of legislation have faced at least one cloture vote in the Senate – that is, a vote to limit further debate and move a bill toward an up-or-down vote, thus effectively ending a filibuster – according to a Pew Research Center analysis of Senate legislative and voting data. Thirteen of those bills have gone on to become law. Among them: a $550 billion infrastructure package, a $280 billion bill aimed at reviving advanced semiconductor manufacturing in the United States, legislation to address a wave of hate crimes against Asian Americans and a gun safety and mental health services bill containing the first new gun restrictions in decades.

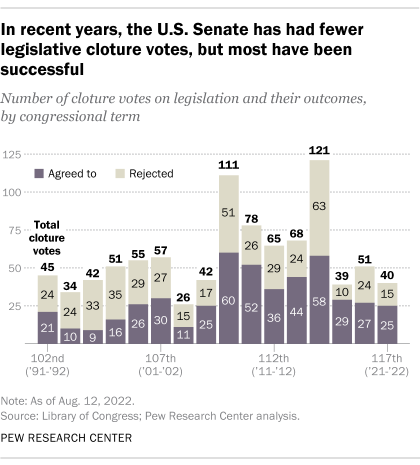

All told, the current Senate had held 40 cloture votes on legislation by early August, when the chamber left for summer break. Of these, cloture was successfully invoked 25 times – among the higher success rates of recent decades. (That figure doesn’t include more than 200 cloture votes on presidential nominations, which only need a simple majority.)

On the other hand, several key Democratic initiatives have tried and failed to clear the 60-vote hurdle. Among them: protecting the right to vote, which was the subject of no fewer than four separate bills; guaranteeing access to abortion services; addressing sex-based wage discrimination; and creating an independent commission (rather than the House select committee) to investigate the Jan. 6, 2021, riot at the U.S. Capitol.

Other significant laws were able to avoid the 60-vote requirement entirely. Some, like the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan and the recently enacted climate, health care and tax package, were passed through a procedure called budget reconciliation and couldn’t be filibustered. Others, such as the first-ever federal anti-lynching law (named for Emmett Till, perhaps the most famous victim of lynching) and the bill making Juneteenth a federal holiday, encountered little or no opposition.

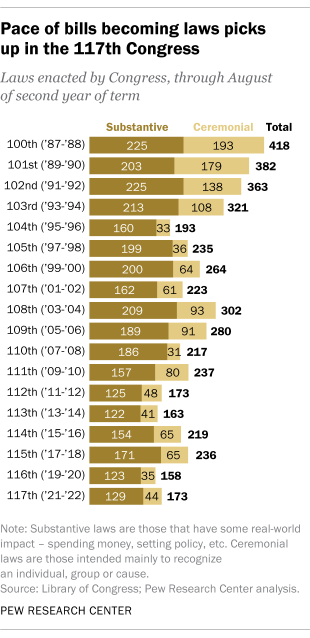

Overall, the current Congress’ legislative track record looks much like that of its predecessor, where Republicans controlled the Senate (and the White House) while Democrats ran the House: 173 public laws enacted as of Aug. 22, 129 of them deemed “substantive” by criteria we’ve used in past analyses, versus 158 laws (123 substantive) for the 116th Congress at a similar point in its term. (We consider laws “substantive” if they change written law, spend money or establish policy, no matter how minor.) Both are below the bar set by the 115th Congress (2017-18), when Republicans had the House-Senate-presidency trifecta: By this time in 2018, Congress had enacted 236 public laws, 171 of them substantive.

Explaining the filibuster and cloture rules

Senate rules generally allow individual senators to talk for as long as they want about almost anything they want. From the earliest days of the republic, senators realized they could use their speechifying ability to block unwelcome legislation. (The House, by contrast, tightly manages its flow of business.) By 1917, though, Senate leadership had had enough and adopted the first cloture rule, enabling debate to be ended by a two-thirds supermajority vote.

The requirement was changed in 1975 to three-fifths of all sitting senators – or 60, assuming there’s no more than one vacancy – in an effort to make breaking filibusters easier. The Senate also changed its rules such that filibustering one bill couldn’t stop the chamber from moving on to other business.

The effect of those changes, however, was to make filibustering easier: Rather than commandeering the floor with hours of talk about fried oyster recipes or poetry recitations, a senator merely needs to indicate his or her willingness to do so. Unless the leadership has 60 votes to invoke cloture, it’s usually not willing to gum up the Senate any more than necessary, and the objectionable measure is effectively sidetracked.

There are limits, however. Following rules changes in 2013 and 2017, judicial nominations (including the Supreme Court) and executive branch appointments now need only a majority vote for cloture. And as mentioned above, budget reconciliation bills can’t be filibustered, though the content of such bills is restricted to taxes, spending and borrowing.

Cloture today and yesterday

Since invoking cloture requires a 60-vote majority, typically it’s the majority-party leadership that decides whether to pursue it – either because they think they have a shot at getting 60 votes, or they want to demonstrate that a minority is obstructing something with broad support.

Of the 40 cloture votes on legislation so far in the current Congress, 30 have attracted votes from 50 senators or more. That’s in line with historical trends: We identified 922 cloture votes connected with legislation since the 102nd Congress in 1991-92, and 88% of them attracted at least 50 votes; 52% gained the 60 votes necessary to limit debate.

More bills experienced at least one cloture vote (61) in the 110th Congress of 2007-08 than in any other Congress in the past three decades, according to the Center’s analysis. That Congress also saw the second-most legislative cloture votes of any in the past three decades: 111, second only to the 121 votes (on 43 bills) in the 114th Congress of 2015-16.

Bear in mind that cloture motions are, at best, an imperfect indicator of the prevalence of filibusters. Cloture isn’t sought on every filibuster, nor is every cloture motion voted on (if, for example, leadership can cut a deal to address the objections of the filibustering senators). Also, because filibustering can occur at almost any stage of the legislative process – any time something has to be voted on, in fact – a single bill can be, and often is, the subject of multiple cloture motions.

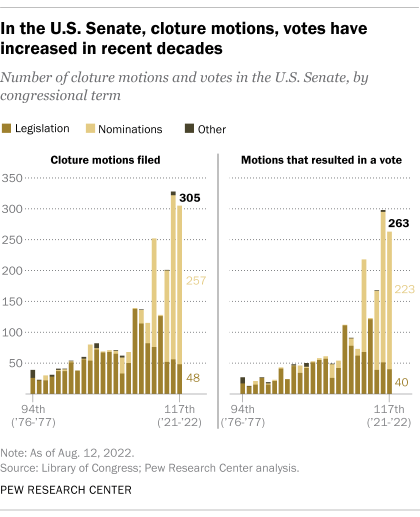

Consider, for example, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act of 2015, a $305 billion highway and transportation funding law. The FAST Act needed seven separate cloture votes to become law: two simply for the Senate to agree to take up the bill, three on various amendments, one to get to an up-or-down vote and one on the question of whether to have a conference with the House to work out differences in their respective versions.

In years past, presidential nominees for federal judgeships and executive branch positions often were filibustered, too. But recent rules changes (in 2013, 2017 and 2019) mean it only takes a simple majority vote to invoke cloture on all nominations, and most of them can only be debated for two hours following cloture. Nowadays, Senate leadership usually moves for cloture on nominations not because of a filibuster threat, but to speed up the confirmation process. And the outcome is seldom in doubt: Out of 257 cloture motions filed to date in the current Congress (on behalf of 246 nominees), only two failed – and one of those passed upon reconsideration.