Note: For an updated analysis about the demographics of the 119th Congress, read our latest research.

The 118th Congress achieved a variety of demographic milestones when its members took office in January. Generation Z is now represented in the national legislature, while Vermont sent a female lawmaker to Capitol Hill for the first time. Still, Congress remains out of step with the broader U.S. population by several demographic measures.

Here are eight charts that show how the profile of Congress has changed over time, using historical data from CQ Roll Call, the Congressional Research Service and other sources.

This Pew Research Center analysis examines the changing demographic profile of Congress over time. It is based on previously published studies by the Center. For information about the sourcing and methodology of these studies, follow the links in the text of this analysis.

Nearly all findings in this analysis are based on voting members of Congress and exclude nonvoting members. The analysis of women in Congress, however, is based on nonvoting as well as voting members.

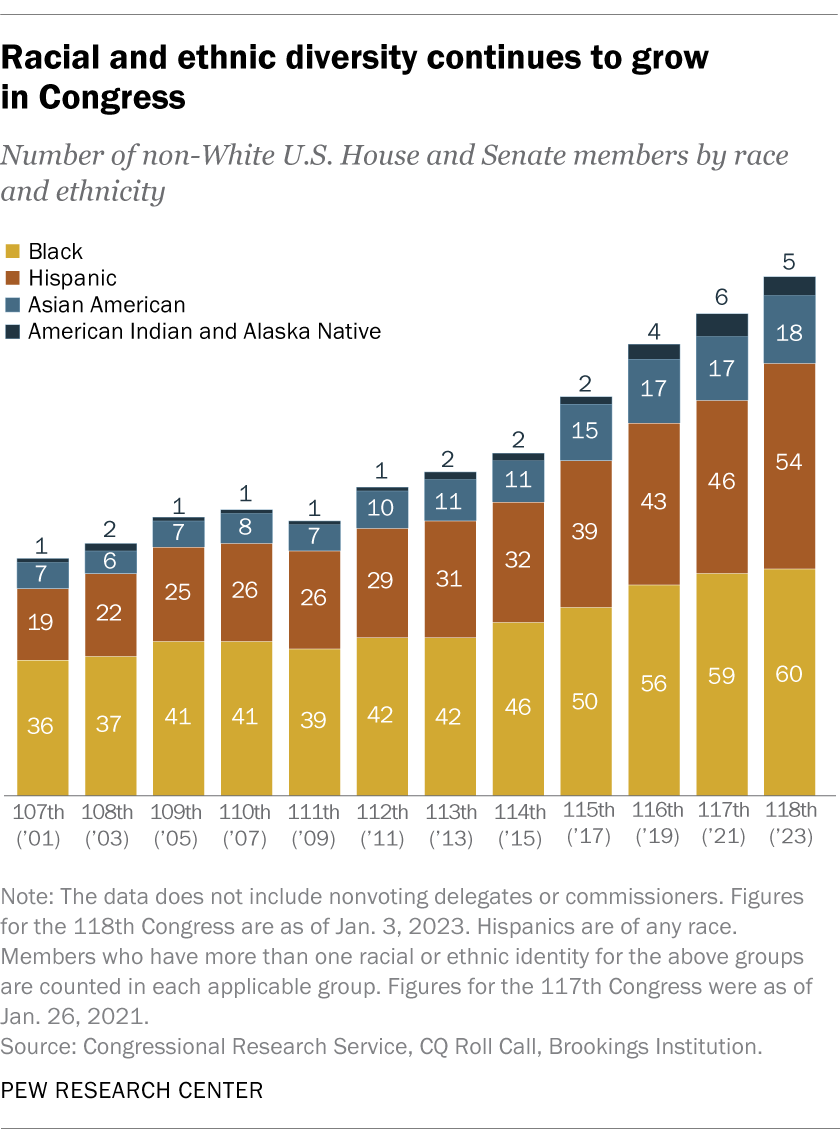

The 118th Congress is the most racially and ethnically diverse in history. Overall, 133 lawmakers identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian American, American Indian, Alaska Native or multiracial. Together, these lawmakers make up a quarter of Congress, including 28% of the House of Representatives and 12% of the Senate. By comparison, when the 79th Congress took office in 1945, non-White lawmakers represented just 1% of the House and Senate combined.

Despite this growing racial and ethnic diversity, Congress remains less diverse than the nation as a whole. Non-Hispanic White Americans account for 75% of voting members in the new Congress, considerably more than their 59% share of the U.S. population.

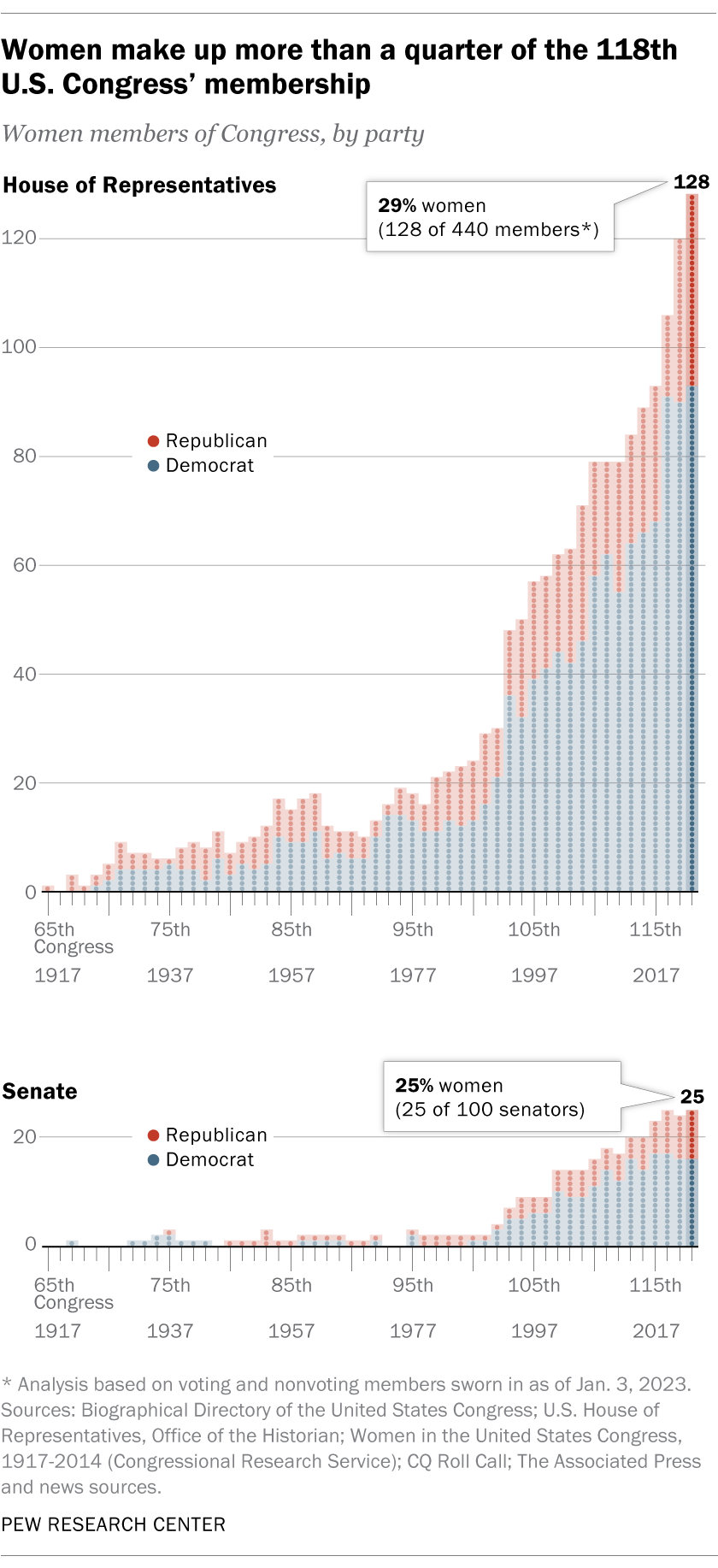

The number of women in Congress is at an all-time high. A little more than a century after Republican Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman elected to Congress, there are 153 women in the national legislature, accounting for 28% of all members. (This includes six nonvoting House members who represent the District of Columbia and U.S. territories, four of whom are women.)

A record 128 women are currently serving in the House, making up 29% of the chamber’s membership. That figure includes 22 newly elected congresswomen, including Becca Balint, a Vermont Democrat who became the first woman and first openly LGBTQ person elected to Congress from the state. With Balint’s election, all 50 states have now had female representation in U.S. Congress at some point.

In the Senate, 25 women are currently serving, tying the record number of seats they held in the 116th Congress. The Senate gained just one new female member:

Republican Katie Britt, who became the first elected woman senator from Alabama. Just as in the previous Congress, four states – Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire and Washington – have all-female Senate delegations.

The House has seen slow but steady growth in the number of women members since the 1920s, when women gained the right to vote. Growth in the Senate has been slower. The Senate did not have more than three women serving at any point until the 102nd Congress, which began in 1991.

The share of women in Congress remains far below their share in the country as a whole (28% vs. 51%).

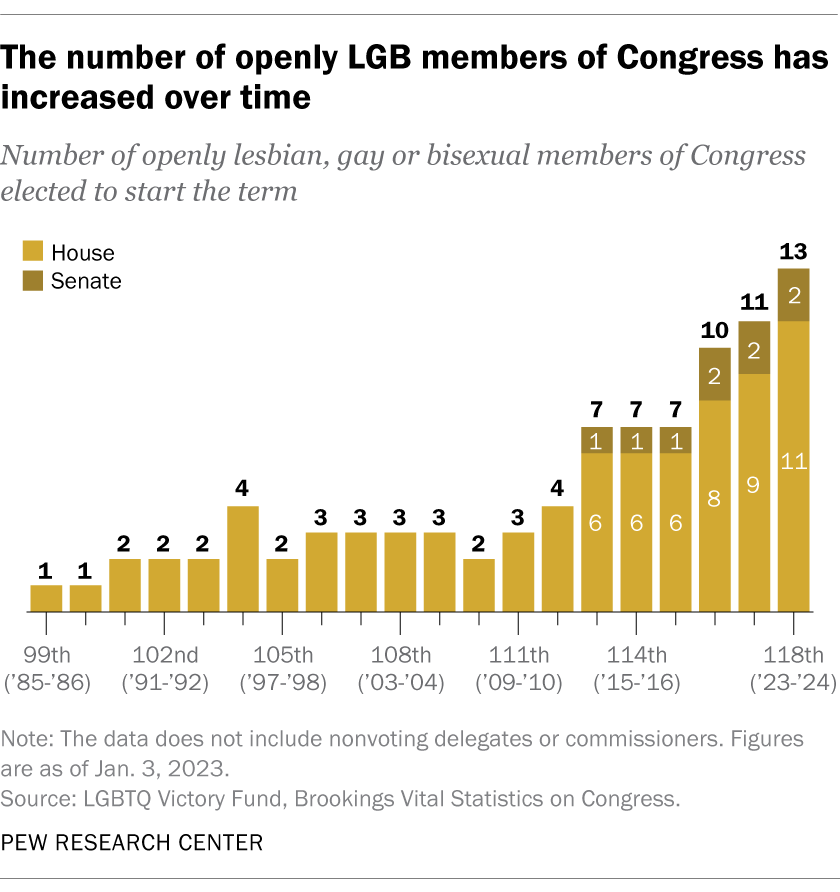

Thirteen voting members of Congress identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual – the highest number in history. This includes two senators and 11 members of the House of Representatives. There have not been any openly transgender members to date.

The number of lawmakers in this group has more than tripled over the last decade. In the 112th Congress of 2011-12, just four members – all representatives – identified as gay or lesbian, and none as bisexual.

The 13 lesbian, gay and bisexual members of Congress accounted for about 2% of the 534 voting lawmakers as of Jan. 3, 2023. By comparison, LGB Americans make up 6.5% of the U.S. adult population overall, according to a 2021 Gallup survey.

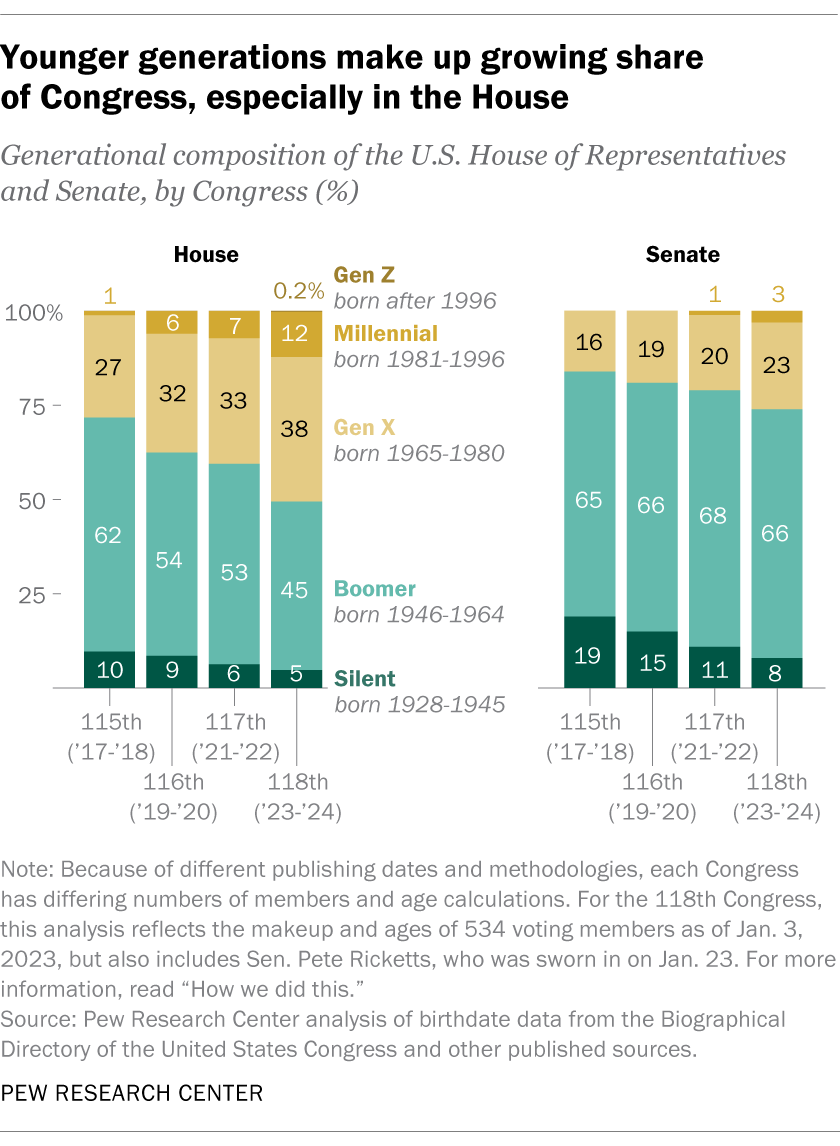

The share of Millennials and Gen Xers in Congress has grown slightly in recent years. In the current Congress, 12% of House members, or 52 lawmakers, are Millennials (a generation ranging in age from 27 to 42 in 2023). This share is up from 1% at the start of the 115th Congress in 2017. And 166 members of the House (38%) are part of Generation X – ages 43 to 58 in 2023 – up from 27% in the 115th Congress.

The Senate now has three Millennial members, up from one – the first ever to be elected – in the last Congress. There are 23 Gen X senators, up from 16 in the 115th Congress.

While younger generations have increased their representation in Congress, older generations still account for the largest share of lawmakers across both chambers. Baby Boomers (who are between the ages of 59 and 77 this year) make up 45% of the House’s voting membership, in addition to 66 of the 100 senators.

The ranks of the Silent Generation (those ages 78 to 95 in 2023) have decreased in Congress in recent years. Across both legislative chambers, 5% of lawmakers, or 29 members, are part of the Silent Generation, down from 14%, or 61 members, in the 115th Congress at the start of 2017.

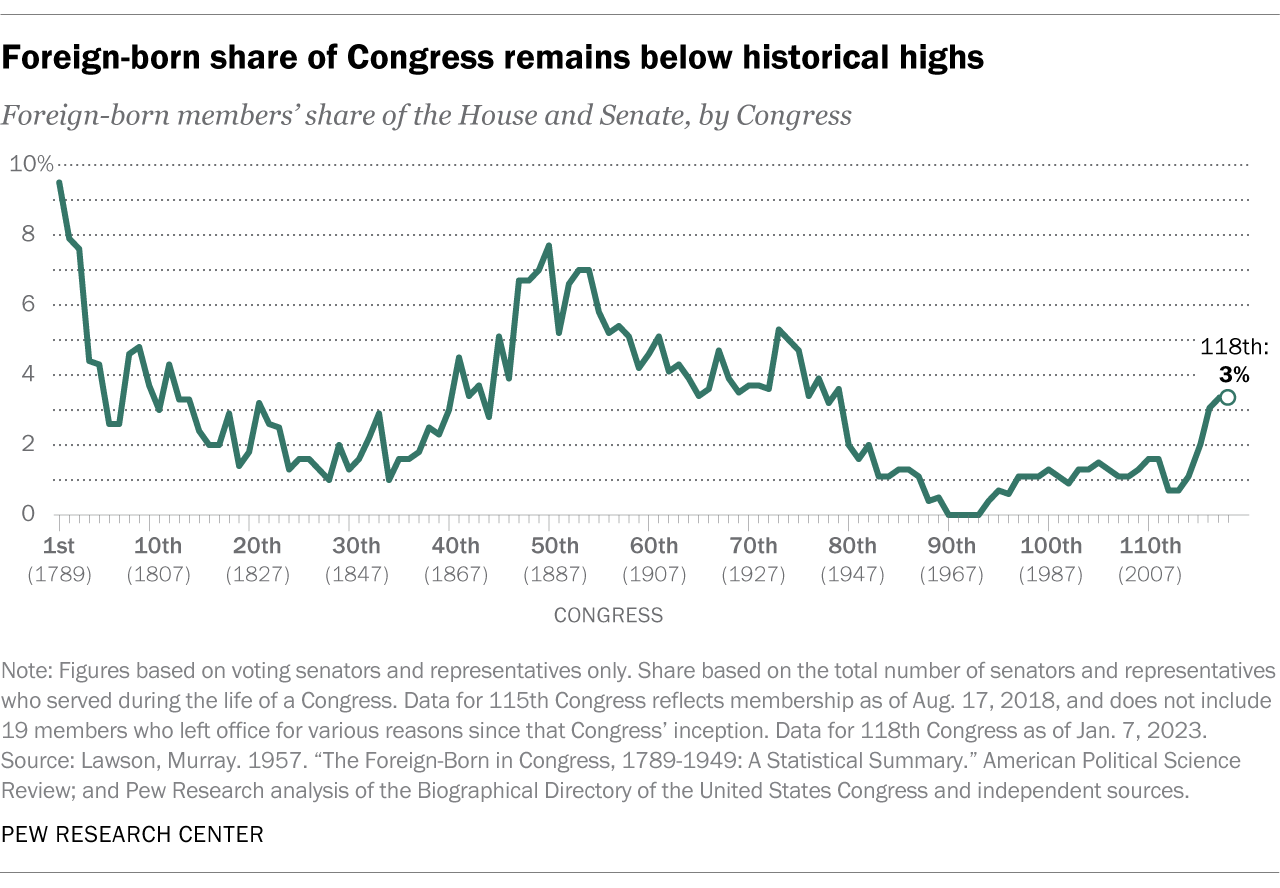

The share of immigrants in Congress has ticked up but remains well below historical highs. There are 18 foreign-born lawmakers in the 118th Congress, including 17 in the House and one in the Senate: Mazie Hirono, a Hawaii Democrat who was born in Japan.

These lawmakers account for 3% of voting members, slightly higher than the share in other recent Congresses, but below the shares in much earlier Congresses. In the 50th Congress of 1887-89, for example, 8% of members were born abroad. The current share of foreign-born lawmakers in Congress is also far below the foreign-born share of the entire U.S. population, which was 13.6% as of 2021.

While the number of foreign-born lawmakers in the current Congress is small, more members have at least one parent who was born in another country. Together, immigrants and children of immigrants account for at least 15% of the new Congress, a slightly higher share than in the last Congress (14%).

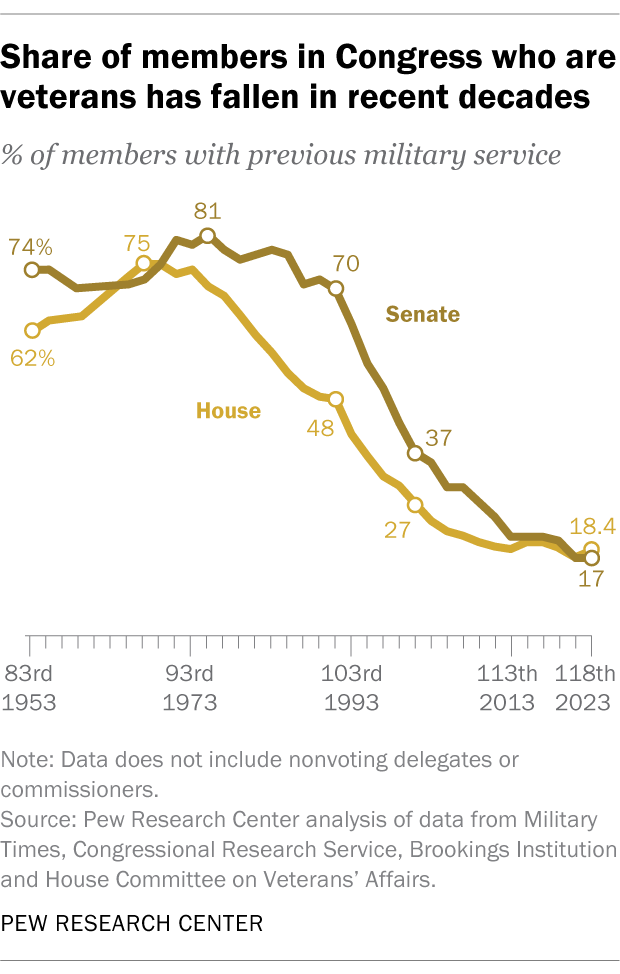

Far fewer members of Congress now have personal military experience than in the past. In the current Congress, 97 members have served in the military at some point in their lives – among the lowest numbers since at least World War II, according to Military Times. There are almost three times as many Republican veterans in the 118th Congress as Democratic veterans (72 vs. 25). Roughly similar shares of current representatives (18.4%) and senators (17%) have served in the military.

Since the second half of the 20th century, there has been a dramatic decrease in members of Congress with military experience. Between 1965 and 1975, at least 70% of lawmakers in each legislative chamber had military experience. The share of members with military experience peaked at 75% in 1967 for the House and at 81% in 1975 for the Senate.

While relatively few members of Congress today have military experience, an even smaller share of Americans do. In 2021, about 6% of U.S. adults were veterans, according to the U.S. Census Bureau – down from 18% in 1980, not long after the end of the military draft era.

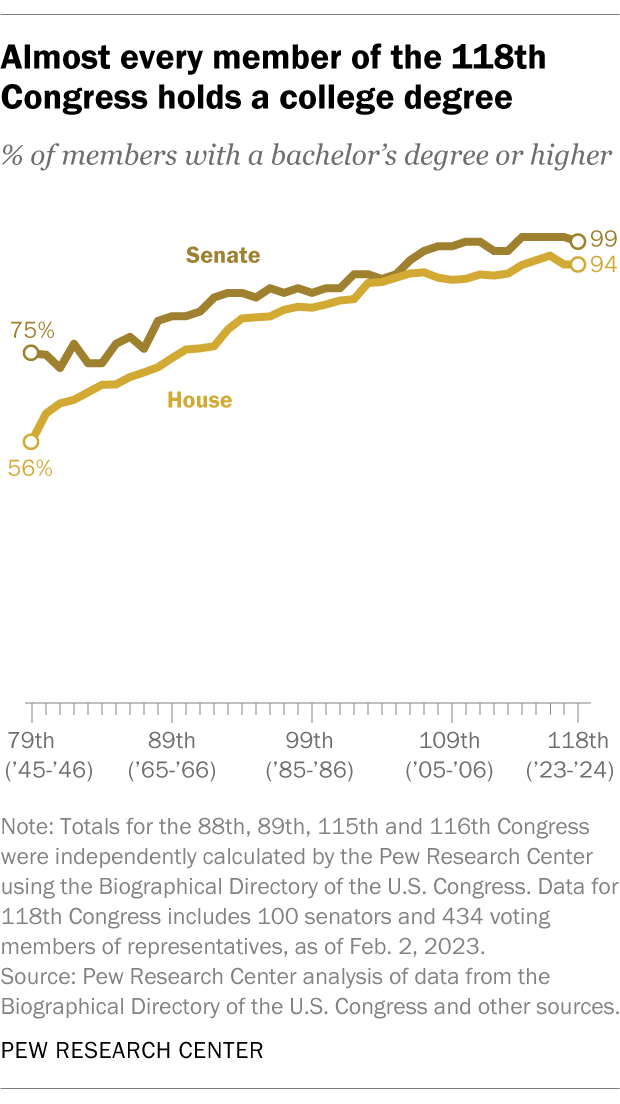

Nearly all lawmakers in Congress have a college degree. In the 118th Congress, 94% of House members and all but one senator have a bachelor’s degree or more education.

In the House, nearly two-thirds of representatives (64%) have a graduate degree. Five representatives (1%) have an associate degree but no bachelor’s. Another 22 members (5%) do not have a degree. This group includes one member who has a professional certification: Democrat Cori Bush of Missouri has a registered nursing diploma.

Among current senators, 78 have at least one graduate degree. Republican Markwayne Mullin of Oklahoma is the lone senator without a bachelor’s degree. He holds an associate degree from the Oklahoma State University of Technology. Sen. Rand Paul, a Kentucky Republican, earned a doctorate in medicine from Duke University Medical School but does not hold a bachelor’s.

The educational attainment of members of Congress far outpaces that of the U.S. adult population. In 2021, around four-in-ten American adults ages 25 and older (38%) had a bachelor’s degree or more education, according to the Census Bureau.

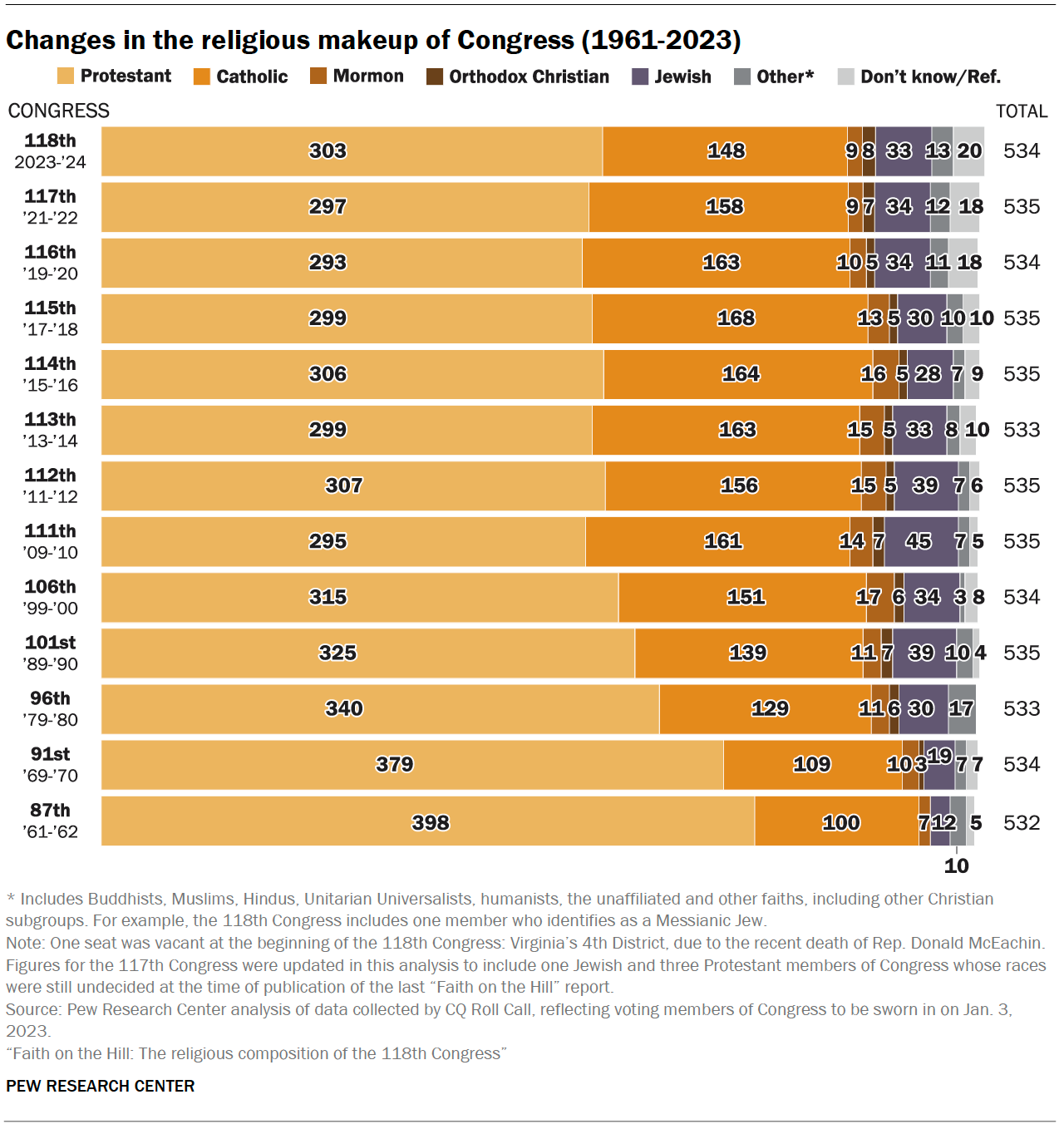

Christians remain the largest religious group in Congress, but their ranks have declined slightly over time. A large majority of current lawmakers in Congress – 469 members – identify as Christian, but that is the lowest total since 2009, when Pew Research Center began analyzing this trend. There were at least 470 Christian lawmakers in each of the last eight Congresses, and the number exceeded 500 in 1970.

Still, Christians’ share in Congress is greater than their proportion of the broader American public. Nearly nine-in-ten congressional members (88%) are Christian as of Jan. 3, 2023, compared with 63% of U.S. adults overall.

By contrast, religiously unaffiliated adults’ share on Capitol Hill is far below their share of the overall U.S. population: While 29% of Americans say they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” just one lawmaker – independent Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona – identifies as religiously unaffiliated. (Democratic Rep. Jared Huffman of California describes himself as humanist, and 20 lawmakers’ religious affiliations are categorized as unknown. Most of those 20 declined to state a religious affiliation when they were asked by CQ Roll Call, which served as the primary data source for the Center’s analysis.)

Note: This is an update to a post originally published on Feb. 2, 2017.