Is China a religious country? A new report from Pew Research Center explains why answering this question is so complex.

Based on formal religious identity, China is the least religious country in the world (among all places where survey data is available). Just one-in-ten Chinese adults self-identify with a religion, according to the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). China also has the largest count of people – about 1 billion adults – who claim no formal religious affiliation.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to explain how China is a more religious nation than levels of formal religious identity alone suggest. It is based on the Center’s August 2023 report, “Measuring Religion in China.” The analysis and the report draw on nationally representative surveys conducted by academic groups in China, including the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) and the 2018 wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS).

This analysis compares the share of Chinese people who formally identify with religion in the 2018 CGSS with the share of people in other places who formally identify with any religion. Data for places outside of China comes from various surveys and censuses used in the Center’s ongoing studies of the global demography of religion, including our report on “The Changing Global Religious Landscape.” For more information on how the 2018 CGSS’s measure of religious identity differs from previous Center estimates of China’s religious composition, read the methodology for the August 2023 Center report.

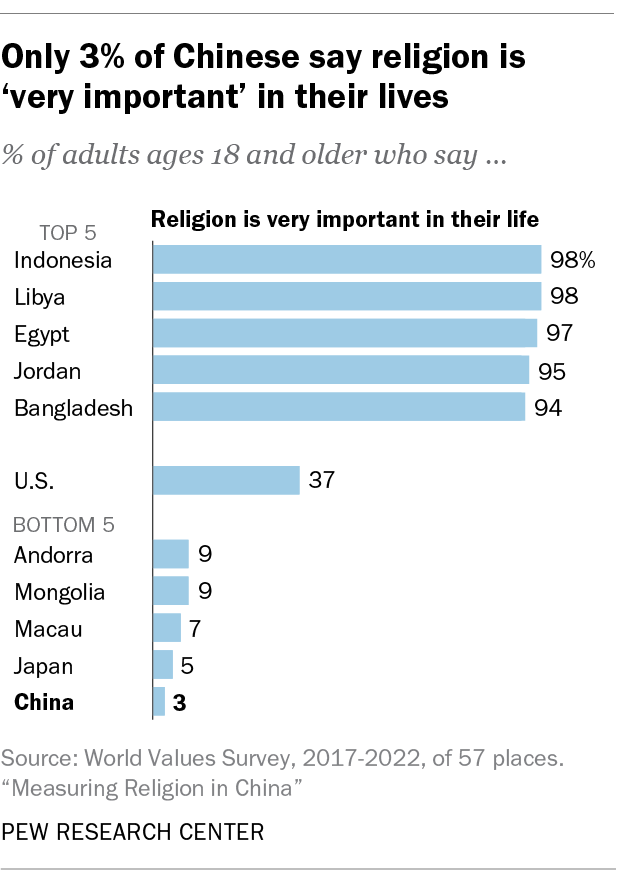

Data on the importance of religion in 57 places, regardless of formal religious identification, comes from the latest wave of the World Values Survey, conducted between 2017 and 2022.

This research is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

Since such a small share of Chinese adults identify with a religion, it may not be surprising that few say religion matters a lot to them. Just 3% of Chinese adults said religion is “very important” in their lives in the 2017-2022 wave of the World Values Survey (WVS). None of the other 56 places surveyed had a lower result.

Yet religion still permeates the everyday lives of many Chinese people who do not claim a religion. Among the total population, minority shares say they believe in religious figures and supernatural forces. But most Chinese people engage in practices premised on belief in unseen forces and spirits.

Chinese people, in other words, are more religious in their practices than in their identities or beliefs.

The challenges of measuring religion in China

Some background information is useful for making sense of how surveys measure religion in China – and the challenges that survey researchers face.

Religion is literally a foreign term in China. When Chinese scholars needed to translate the English word “religion” in Western texts, they adopted the term zongjiao, which implies organized forms of religion, such as the five religions officially recognized by the Chinese government: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism and Catholicism. Many broadly religious beliefs and practices are not captured by the term zongjiao.

Furthermore, although the Chinese government officially permits many forms of religion, it tightly regulates religious institutions. The government teaches that religion is a backward mindset, and it places many restrictions on religion. Members of the Chinese Communist Party are officially banned from practicing religion.

Religious and spiritual expression in China

In China, belief in gods and other religious figures is more common than formal religious identity.

For example, according to the 2016 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) survey, 18% of Chinese adults believe in Taoist deities and 33% believe in Buddha and/or enlightened beings (Buddhist deities). The share of people who believe in a religious figure is typically broader than the share who identify with any one religion, and many Chinese report belief in several religious figures or forces.

Broadly religious practices are common elements of life in China, and some are practiced by substantial shares of the population. For example, about a quarter of adults (26%) burn incense to worship deities at least a few times a year. Often this ritual is tied to a request for blessings, such as for good scores on school exams.

One of the most common customs in China is visiting the gravesites of family members. Three-quarters of respondents in the 2018 CGSS visited gravesites at least once in the previous year. There are several special days each year designated for the veneration of ancestors.

When Chinese visit gravesites, they often perform rituals that ostensibly help their deceased ancestors who now live in another realm (the underworld). These rituals include burning “spirit money” and offering food and drink, based on the idea that the offerings can be carried over to benefit ancestors in their spiritual realm. However, only 10% of Chinese believe dead people have living spirits (“ghosts”). In her ethnographic study of gravesite rituals, Duke University sociologist Anna Sun finds that the meaningfulness of these gravesite practices does not require conviction that the offerings are supernaturally transmitted to deceased loved ones.

Other common elements of life in China reflect a view of the world as enchanted. Nearly half of Chinese adults (47%) believe in fengshui, a traditional Chinese practice of arranging objects and physical space to promote harmony between humans and the environment, according to the 2018 CFPS.

Many Chinese consult the Chinese almanac or a fengshui expert to schedule events big and small around dates labeled as lucky (“auspicious”) or unlucky (“inauspicious”) based on astrology, astronomy and season. About a quarter (24%) care “very much” about choosing auspicious days for special events, according to the 2018 CGSS. Occasions like moving into a new house or buying a car often involve a ceremony in which incense is burned and spirit money is offered. Chinese businesses may consult with fengshui masters about store openings and proper rituals for major events.

In China, most people do not feel obliged to pay respects to one or more gods on a regular basis. Rather, they tend to engage in religious activity as needs arise. A wide range of gods and rituals are available, so chosen practice is related to how well a god or ritual is expected to respond to a person’s request. Christians and Muslims are exceptions to this pattern. They typically attend church or mosque frequently and lean on their own religious tradition for their needs.

Based on common survey measures of formal religion (zongjiao), China is not a very religious country. In fact, based on the ideology of the ruling Chinese Community Party, China is an atheist nation. And yet, based on common behaviors, China is a country in which religion, broadly understood, continues to play a significant role in the lives of a large share of the population.