People in Japan are preparing to celebrate Obon – a festival devoted to celebrating ancestors that features lighting lanterns and maintaining family gravesites. In Japan, 85% of adults say their family has such a gravesite, and 79% say they have looked after this gravesite by sweeping or cleaning it in the past year, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

Obon is one of many Asian festivals focused on the veneration and celebration of ancestors. Others include Sat Thai in Thailand, and both the Hungry Ghost Festival and Tomb-Sweeping Day (Qingming) in several places in East and Southeast Asia. While the specific activities vary, these festivals often include traditions such as visiting family gravesites or lighting incense.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to assess the extent to which adults throughout Asia participate in various practices venerating ancestors.

Data comes from two Pew Research Center projects. Data for Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam comes from a Center survey of 10,390 adults conducted from June to September 2023. Data for Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka and Thailand comes from a Center survey of 13,122 adults conducted from June to September 2022.

Interviews were conducted over the phone in six places: Hong Kong, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. In Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam, interviews took place face-to-face.

These surveys are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design. Data was weighted to account for different probabilities of selection and to align with demographic benchmarks for the adult populations.

For more information, read the 2023 survey’s full list of questions and responses, the 2022 survey’s full list of questions and responses, and our survey methodology.

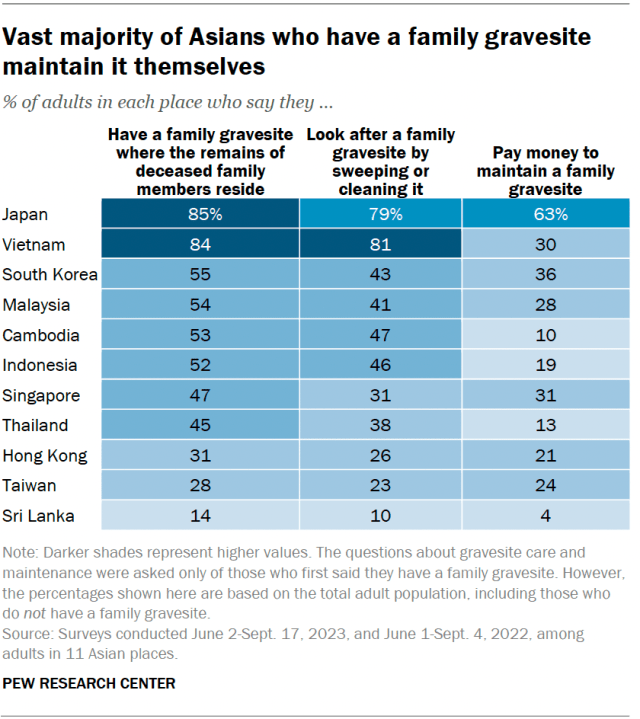

In most of the East and Southeast Asian places the Center surveyed in 2022 and 2023, roughly half of adults or more say that they have a family gravesite – a place where the bodies or cremated ashes of family members are interred.

Among the places surveyed, people in Japan (85%) and Vietnam (84%) are most likely to say they have a family gravesite. However, the remains of family members tend to be handled very differently in these two places. Nearly all adults in Japan say their family cremates and buries the remains of loved ones, while most adults in Vietnam say their family buries but does not cremate deceased family members.

While not everyone we surveyed reports having a family gravesite, large majorities of those who do have such a place say they or someone in their household looks after it by sweeping or cleaning it. In general, people in the places we surveyed are less likely to say they pay money to maintain these gravesites.

Ancestor veneration rituals

We also asked survey respondents in East Asia and Vietnam if they have done each of the following in the past 12 months to honor or take care of their ancestors:

- Burned incense

- Offered food, water or drinks

- Offered flowers or lit candles

- Offered money or other things they may need in the afterlife

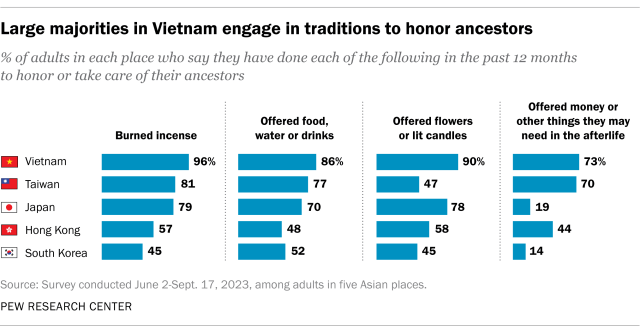

These rituals are relatively widespread across the region and are especially common in Vietnam. For example, nearly all Vietnamese adults say they have burned incense in the past 12 months to care for their ancestors.

Among the practices we asked about, the least common is offering ancestors money or other things that they may need in the afterlife. Still, majorities in Vietnam (73%) and Taiwan (70%) say they do this.

Across the region, most religiously unaffiliated adults, Buddhists and Taoists (also spelled Daoists) say they have done at least one of these rituals in the past year. For instance, 59% of Japan’s religiously unaffiliated adults say they have offered food, water or drinks in the past 12 months to care for their ancestors.

Christians generally are less likely to engage in these sorts of activities. However, many Vietnamese Christians have burned incense, offered flowers or lit candles to care for ancestors in the last year.

Marking death anniversaries

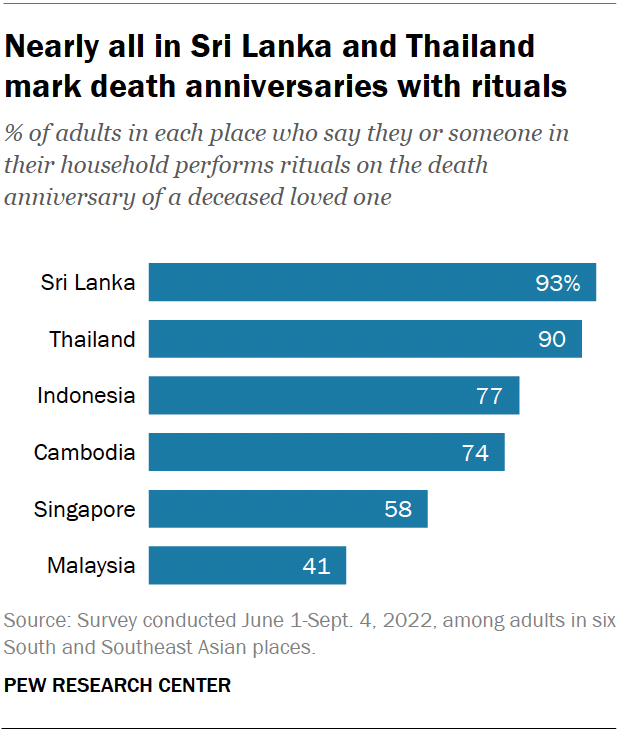

In our 2022 survey of countries in South and Southeast Asia, we asked respondents if they or someone in their household performs rituals on the death anniversary of a deceased loved one.

Majorities in most places surveyed say that someone in their household does this, including nine-in-ten or more in Sri Lanka (93%) and Thailand (90%).

Buddhists in the region are somewhat more likely than Muslims and Christians to say that someone performs these rituals.