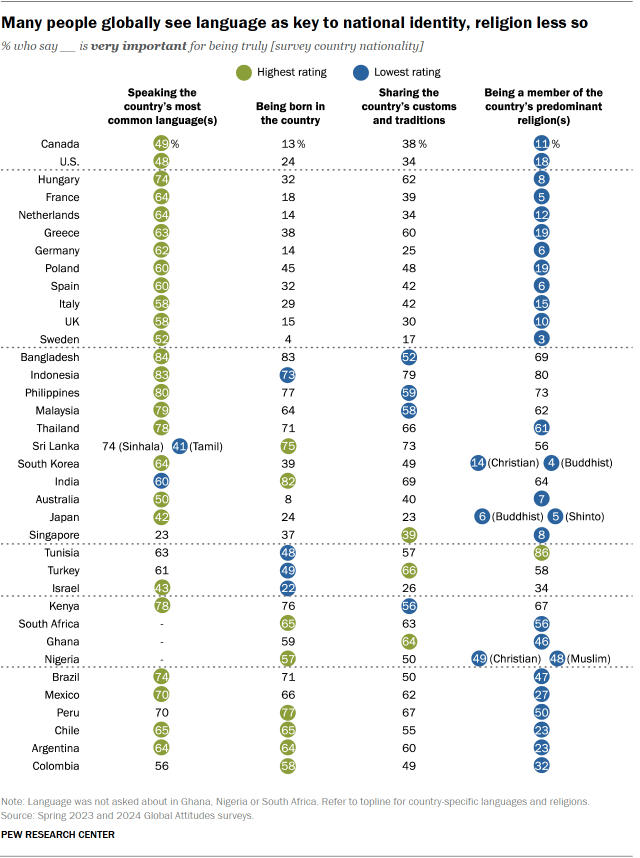

When asked what it takes to “truly” belong in a country, many people globally say speaking the local language is key. In fact, more people see this as very important to national identity than say the same about being born in their country or sharing its customs and traditions. The factor perceived as least important is being a member of the historically predominant religion, according to Pew Research Center surveys conducted in 36 countries in 2023 and 2024.

In many countries, attitudes about these aspects of national identity vary by age, education and ideology. This includes in the United States, where conservatives and liberals are deeply divided on what makes someone truly American.

In this analysis, we take a closer look at these findings, which are based on nationally representative surveys of more than 65,000 people around the world.

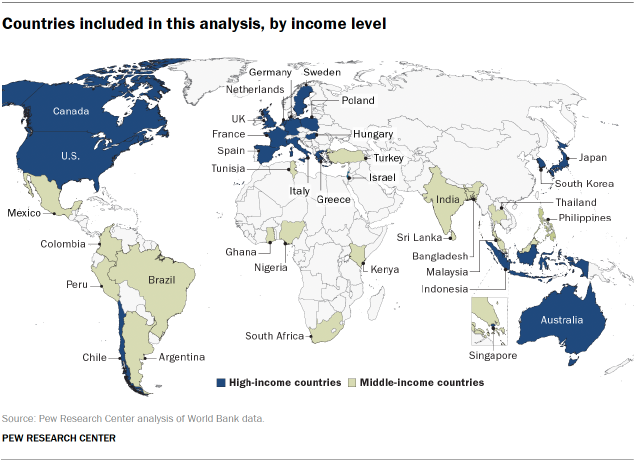

This Pew Research Center analysis focuses on public opinion of the importance of language, customs and traditions, birthplace, and religion as components of national identity in 36 countries.

This analysis draws on and compares data from surveys conducted in 2023 and 2024. The language, customs and traditions, and birthplace questions were asked in 2023 in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The same questions were asked in 2024 in Bangladesh, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, India, Malaysia, Peru, the Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey and the United States. The religion question was asked in all 36 countries in 2024.

For non-U.S. data, this analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 41,503 adults conducted from Jan. 5 to May 22, 2024, and surveys of 24,674 adults conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel.

In the U.S., we surveyed 3,600 adults from April 1 to April 7, 2024. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Throughout the analysis, we evaluate respondents’ attitudes based on where they place themselves on an ideological scale. We asked about political ideology using several slightly different scales and categorized people as being on the ideological left, center or right.

- In most countries, we asked people to place themselves on a scale ranging from “Extreme left” to “Extreme right.” The question was asked this way in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and the United Kingdom.

- In Australia, the scale ranged from “Left” to “Right.”

- In Japan, Singapore and Thailand, ideology was measured on a scale from “Extremely progressive” to “Extremely conservative.”

- In the U.S., ideology is defined as conservative (right), moderate (center) and liberal (left).

- Ideology was not asked about in Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Sri Lanka or Tunisia.

To compare educational groups across countries, we standardize education levels based on the UN’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).

For this analysis, we grouped countries into high-income and middle-income categories based on definitions from the World Bank.

Prior to 2024, combined totals were based on rounded topline figures. For all analyses beginning in 2024, totals are based on unrounded topline figures, so combined totals might be different than in previous years. Refer to the 2024 topline to see our new rounding procedures applied to past years’ data.

Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

Language and national identity

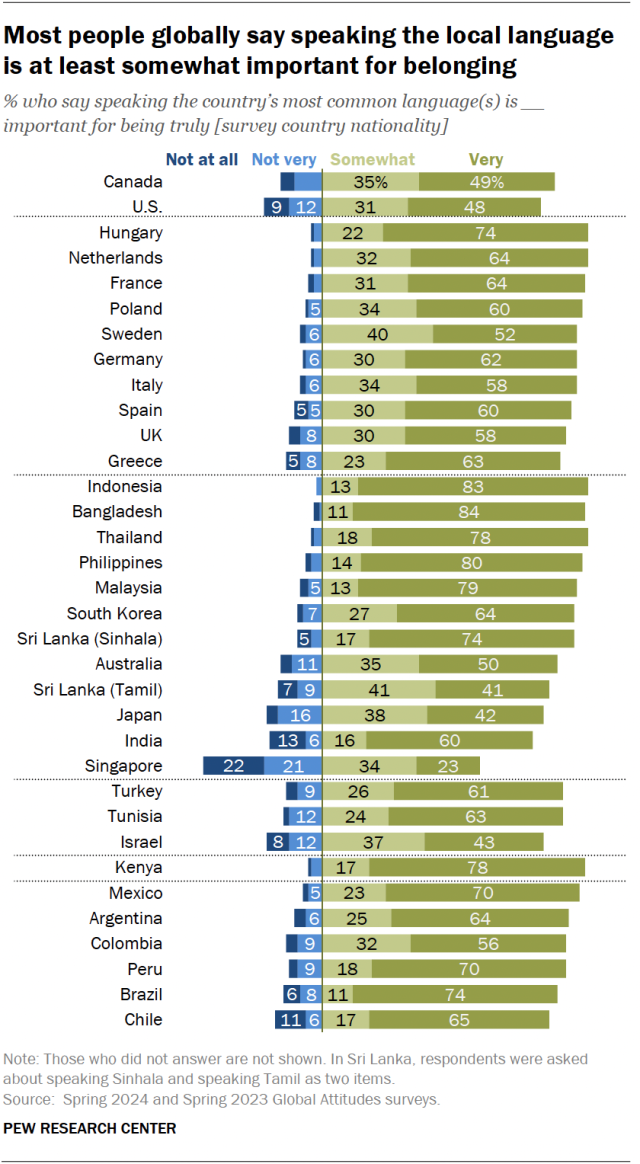

Globally, large majorities say speaking the country’s most common language is at least somewhat important for true belonging. And in many countries, large shares see this as very important.

One notable exception is Singapore. Only about a quarter of adults there say it is very important to speak Mandarin in order to be truly Singaporean. (Singapore has three other official languages: English, Malay and Tamil.)

Views on the importance of language to national belonging vary by age, education and ideology.

In many countries, older people are more likely than younger people to see language as highly important to national identity. For example, in the Netherlands, 72% of adults ages 40 and older say that speaking Dutch is very important, compared with 45% of adults under 40.

In several countries, people with less education are also more likely to see language as very important to national belonging.

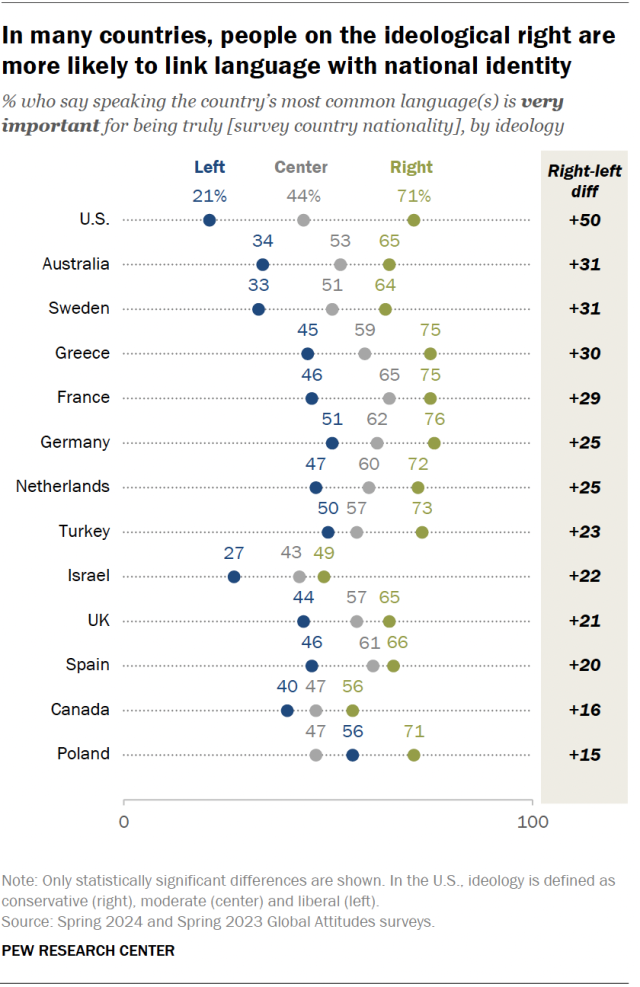

Some of the biggest demographic differences are related to ideology. In many countries, people on the ideological right are significantly more likely than people on the left to say speaking the local language is very important to national belonging. In the U.S., for instance, conservatives are 50 percentage points more likely than liberals to say speaking English is very important for being truly American (71% vs. 21%).

In several European countries surveyed, supporters of right-wing populist parties are also more likely to see language as very important to national identity. For example, in Sweden, supporters of the Sweden Democrats are 40 points more likely than non-supporters to say that speaking Swedish is very important for being truly Swedish (83% vs. 43%).

We asked people in 36 countries whether it’s important to speak a particular language or be a member of a particular religion to truly belong there. For each country, we selected the most common language(s) and historically predominant religion(s), with input from local advisers.

In Canada and Sri Lanka, we asked about more than one language. In Canada, we asked about the importance of speaking “English or French” as one item. And in Sri Lanka, we asked all respondents about the importance of speaking Sinhala and speaking Tamil as separate questions.

In Japan, Nigeria and South Korea, we asked all respondents separately about two religions. In Japan, we asked about both Buddhism and Shinto. In Nigeria, we asked about Christianity and Islam. In South Korea, we asked about Christianity and Buddhism.

How important do you think each of the following is for being truly [survey country nationality] – very important, somewhat important, not too important or not at all important?

| Country | Being able to speak … | Being a … |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | English or French | Christian |

| U.S. | English | Christian |

| France | French | Christian |

| Germany | German | Christian |

| Greece | Greek | Christian |

| Hungary | Hungarian | Christian |

| Italy | Italian | Christian |

| Netherlands | Dutch | Christian |

| Poland | Polish | Christian |

| Spain | Spanish | Christian |

| Sweden | Swedish | Christian |

| UK | English | Christian |

| Australia | English | Christian |

| Bangladesh | Bengali | Muslim |

| India | Hindi | Hindu |

| Indonesia | Indonesian | Muslim |

| Japan | Japanese | Buddhist, Shinto |

| Malaysia | Bahasa Malaysia | Muslim |

| Philippines | Filipino | Christian |

| Singapore | Mandarin | Buddhist |

| South Korea | Korean | Christian, Buddhist |

| Sri Lanka | Sinhala, Tamil | Buddhist |

| Thailand | Thai | Buddhist |

For more on views of religion and national identity, read our recent report “Comparing Levels of Religious Nationalism Around the World.”

Customs, traditions and national identity

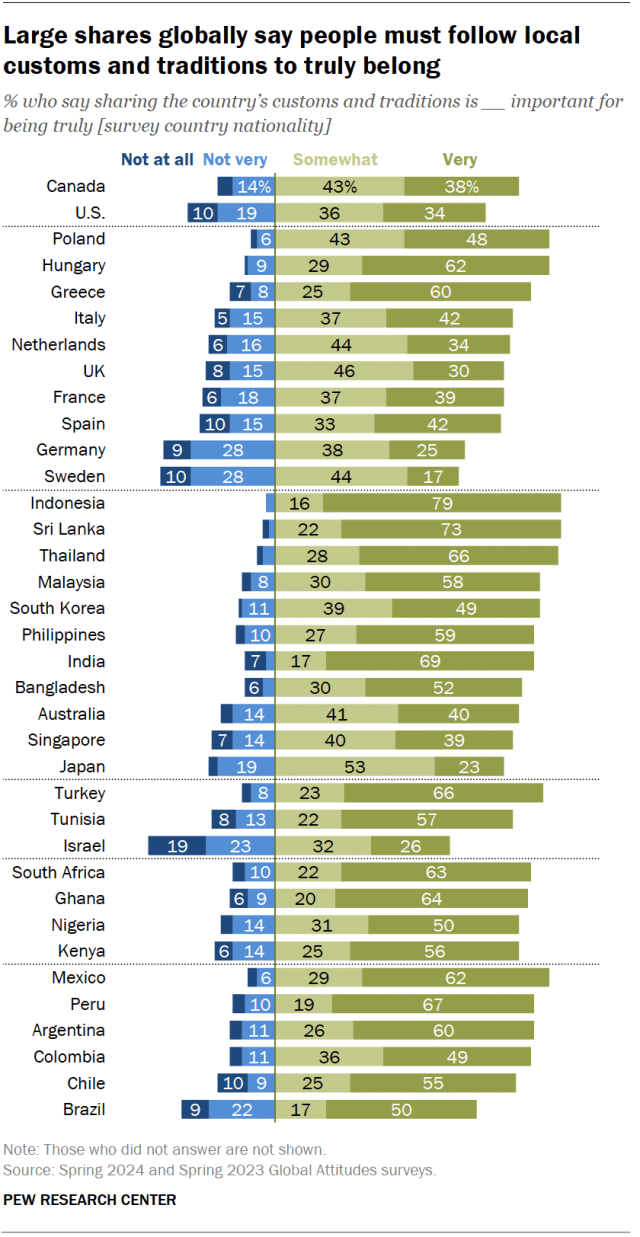

Majorities around the world also say following local customs and traditions is at least somewhat important for true belonging. But views differ widely over whether this is very important.

In particular, people in middle-income countries are more likely than their counterparts in high-income countries to see this as very important. In middle-income Indonesia, for example, 79% of adults say following their country’s customs and traditions is very important for national belonging. Far fewer adults express this view in high-income Australia (40%), Singapore (39%) or Japan (23%).

Views on this question differ between certain high-income countries, too. For example, around six-in-ten adults in Hungary and Greece (62% and 60%) say it is very important to follow local customs in order to truly belong. Only a quarter of Germans and 17% of Swedes share that view.

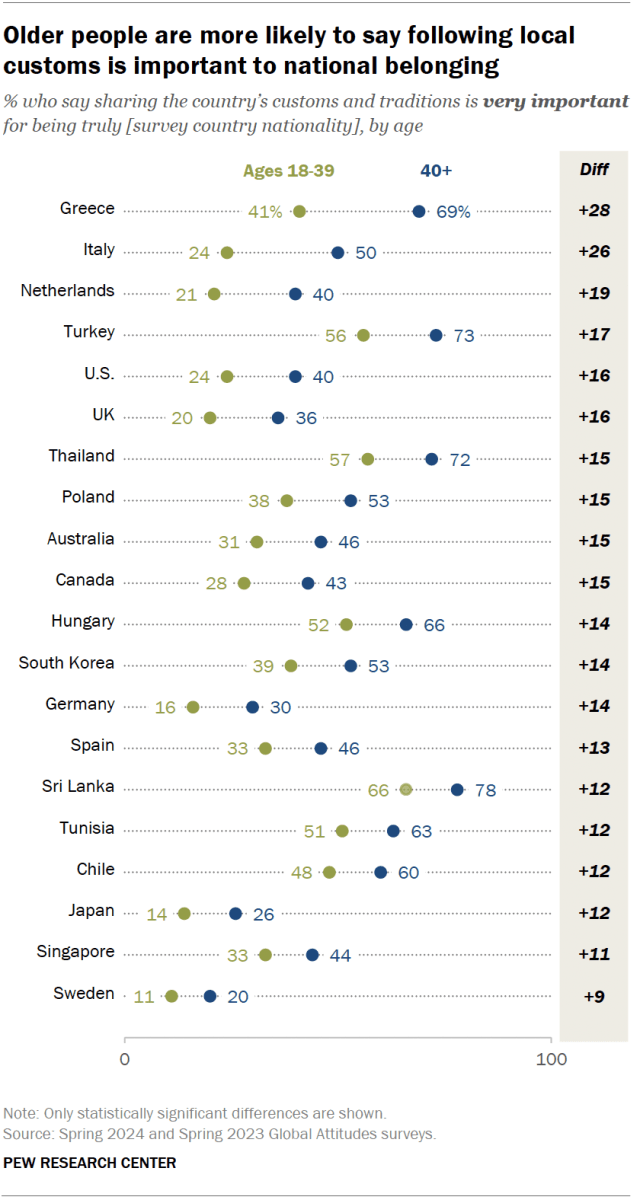

Older people tend to value customs more than younger people do. Italians ages 40 and older, for instance, are about twice as likely as younger Italian adults (50% vs. 24%) to say it is very important to follow local customs and traditions to be truly Italian.

People with less education and those on the ideological right are also particularly likely to see customs and traditions as very important.

In the U.S., 54% of conservatives – compared with 14% of liberals – say sharing in American customs is very important to national belonging. This 40-point difference is the largest ideological divide across all the countries surveyed.

In Europe, people who have a favorable view of populist parties are more likely than those with an unfavorable view to prioritize local customs and traditions. In the United Kingdom, for example, supporters of Reform UK are 35 points more likely than nonsupporters (55% vs. 20%) to say following local customs and traditions is very important to being truly British.

Birthplace and national identity

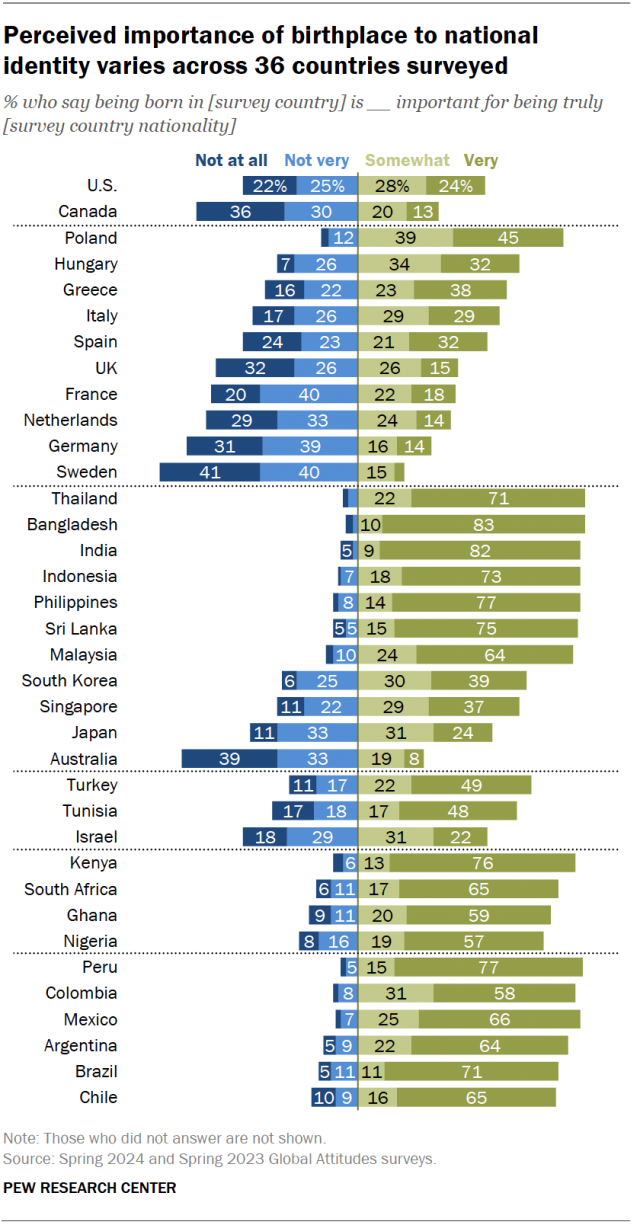

Views on the importance of birthplace to national identity are somewhat mixed across the countries we surveyed.

In most high-income countries – which are often home to sizable immigrant populations – fewer than half of adults say that being born in their country is very important for true belonging. In Sweden, only 4% say that being born in Sweden is very important for being truly Swedish. Similarly small shares say this in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.

In the middle-income countries surveyed, by contrast, large majorities see birthplace as a very important aspect of national identity. In Bangladesh and India, around eight-in-ten adults say that being born in their country is very important for being truly Bangladeshi or Indian, respectively. Around three-quarters or more say the same in Indonesia, Kenya, Peru, the Philippines and Sri Lanka.

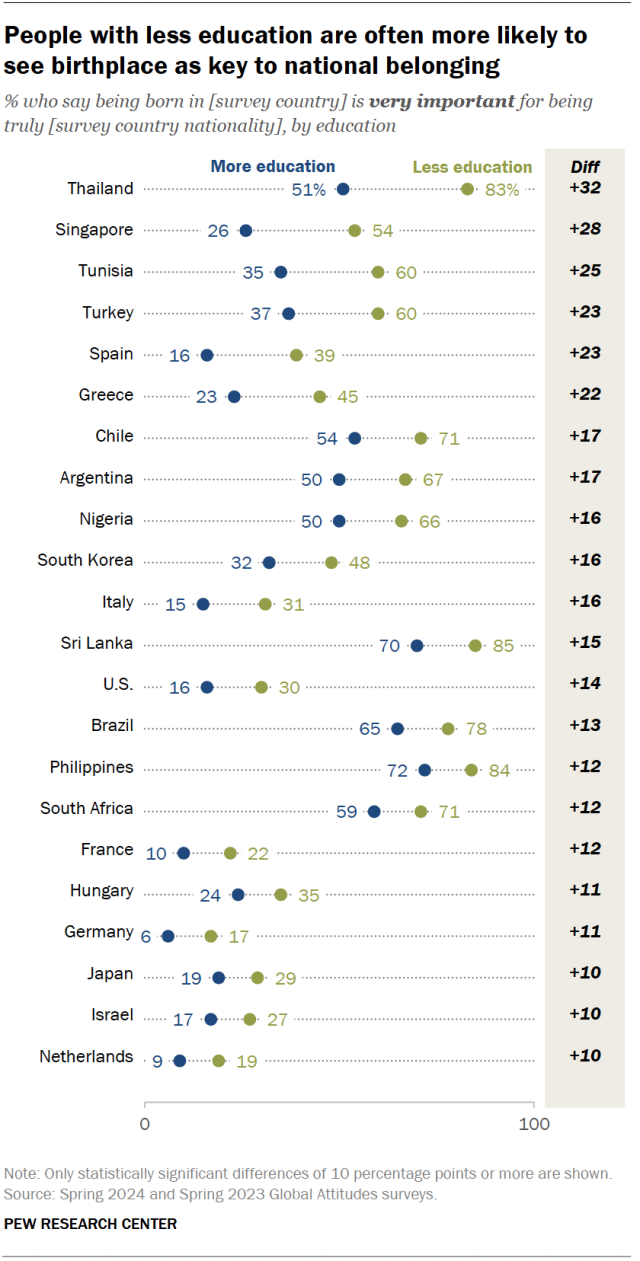

In most countries surveyed, views on this question vary by education. People with less education are significantly more likely to say that being born in their country is very important to being a true national. This gap is most prominent in Thailand, where 83% of adults with less education – but only 51% of those with more education – see birthplace as very important for being truly Thai. In 21 other countries, there is also a double-digit difference by education on this question.

Views also vary by ideology and age. In many countries, people on the ideological right are more likely than those on the ideological left to see birthplace as a key facet of national identity.

And as with the other aspects of national identity, supporters of European right-wing populist parties are more likely to say being born in their country is very important for being a true national. For example, in Spain, over half of adults who support the Vox party say that being born in Spain is very important to being truly Spanish. Only a quarter of other Spaniards share this view.

Older adults are also generally more likely than younger people to say being born in the country is very important for being a true national.

In the U.S., the ideological divide stands out

Compared with people in other high-income countries, Americans are particularly divided along ideological lines when it comes to their assessments of national identity. On all four measures included in this survey, conservatives are at least 20 points more likely than liberals to see each as very important for being truly American.

Conservatives in the U.S. tend to have similar views on these questions as conservatives (people on the ideological right) in other countries. American liberals, however, stand out in some ways from people on the ideological left in other countries. For example, U.S. liberals are less likely than people on the ideological left elsewhere to say it’s very important for someone to speak the local language in order to truly belong.

Note: Here are the questions used for the analysis, along with responses, and the survey methodology.