Our approach to generational analysis has evolved to incorporate new considerations. Learn more about how we currently report on generations, and read tips for consuming generations research.

For decades, Pew Research Center has been committed to measuring public attitudes on key issues and documenting differences in those attitudes across demographic groups. One lens often employed by researchers at the Center to understand these differences is that of generation.

Generations provide the opportunity to look at Americans both by their place in the life cycle – whether a young adult, a middle-aged parent or a retiree – and by their membership in a cohort of individuals who were born at a similar time.

As we’ve examined in past work, generational cohorts give researchers a tool to analyze changes in views over time. They can provide a way to understand how different formative experiences (such as world events and technological, economic and social shifts) interact with the life-cycle and aging process to shape people’s views of the world. While younger and older adults may differ in their views at a given moment, generational cohorts allow researchers to examine how today’s older adults felt about a given issue when they themselves were young, as well as to describe how the trajectory of views might differ across generations.

Pew Research Center has been studying the Millennial generation for more than a decade. But by 2018, it became clear to us that it was time to determine a cutoff point between Millennials and the next generation. Turning 38 this year, the oldest Millennials are well into adulthood, and they first entered adulthood before today’s youngest adults were born.

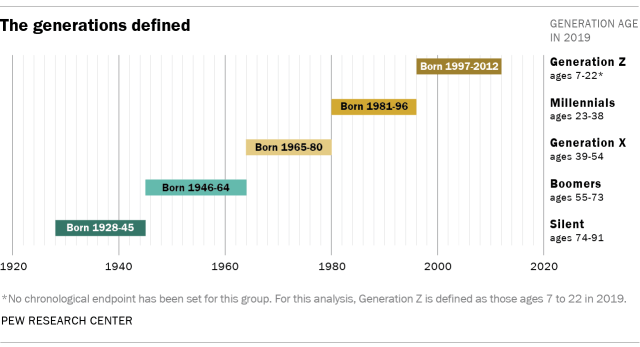

In order to keep the Millennial generation analytically meaningful, and to begin looking at what might be unique about the next cohort, Pew Research Center decided a year ago to use 1996 as the last birth year for Millennials for our future work. Anyone born between 1981 and 1996 (ages 23 to 38 in 2019) is considered a Millennial, and anyone born from 1997 onward is part of a new generation.

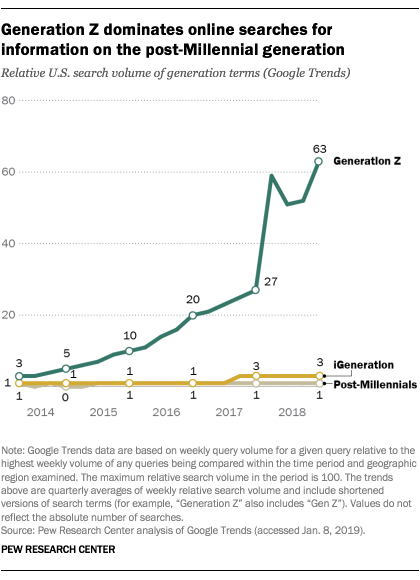

Since the oldest among this rising generation are just turning 22 this year, and most are still in their teens or younger, we hesitated at first to give them a name – Generation Z, the iGeneration and Homelanders were some early candidates. (In our first in-depth look at this generation, we used the term “post-Millennials” as a placeholder.) But over the past year, Gen Z has taken hold in popular culture and journalism. Sources ranging from Merriam-Webster and Oxford to the Urban Dictionary now include this name for the generation that follows Millennials, and Google Trends data show that “Generation Z” is far outpacing other names in people’s searches for information. While there is no scientific process for deciding when a name has stuck, the momentum is clearly behind Gen Z.

Generational cutoff points aren’t an exact science. They should be viewed primarily as tools, allowing for the kinds of analyses detailed above. But their boundaries are not arbitrary. Generations are often considered by their span, but again there is no agreed upon formula for how long that span should be. At 16 years (1981 to 1996), our working definition of Millennials is equivalent in age span to their preceding generation, Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980). By this definition, both are shorter than the span of the Baby Boomers (19 years) – the only generation officially designated by the U.S. Census Bureau, based on the famous surge in post-WWII births in 1946 and a significant decline in birthrates after 1964.

Unlike the Boomers, there are no comparably definitive thresholds by which later generational boundaries are defined. But for analytical purposes, we believe 1996 is a meaningful cutoff between Millennials and Gen Z for a number of reasons, including key political, economic and social factors that define the Millennial generation’s formative years.

Most Millennials were between the ages of 5 and 20 when the 9/11 terrorist attacks shook the nation, and many were old enough to comprehend the historical significance of that moment, while most members of Gen Z have little or no memory of the event. Millennials also grew up in the shadow of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which sharpened broader views of the parties and contributed to the intense political polarization that shapes the current political environment. And most Millennials were between 12 and 27 during the 2008 election, where the force of the youth vote became part of the political conversation and helped elect the first black president. Added to that is the fact that Millennials are the most racially and ethnically diverse adult generation in the nation’s history. Yet the next generation – Generation Z – is even more diverse.

Beyond politics, most Millennials came of age and entered the workforce facing the height of an economic recession. As is well documented, many of Millennials’ life choices, future earnings and entrance to adulthood have been shaped by this recession in a way that may not be the case for their younger counterparts. The long-term effects of this “slow start” for Millennials will be a factor in American society for decades.

Technology, in particular the rapid evolution of how people communicate and interact, is another generation-shaping consideration. Baby Boomers grew up as television expanded dramatically, changing their lifestyles and connection to the world in fundamental ways. Generation X grew up as the computer revolution was taking hold, and Millennials came of age during the internet explosion.

In this progression, what is unique for Generation Z is that all of the above have been part of their lives from the start. The iPhone launched in 2007, when the oldest Gen Zers were 10. By the time they were in their teens, the primary means by which young Americans connected with the web was through mobile devices, WiFi and high-bandwidth cellular service. Social media, constant connectivity and on-demand entertainment and communication are innovations Millennials adapted to as they came of age. For those born after 1996, these are largely assumed.

The implications of growing up in an “always on” technological environment are only now coming into focus. Recent research has shown dramatic shifts in youth behaviors, attitudes and lifestyles – both positive and concerning – for those who came of age in this era. What we don’t know is whether these are lasting generational imprints or characteristics of adolescence that will become more muted over the course of their adulthood. Beginning to track this new generation over time will be of significant importance.

Pew Research Center is not the first to draw an analytical line between Millennials and the generation to follow them, and many have offered well-reasoned arguments for drawing that line a few years earlier or later than where we have. Perhaps, as more data are collected over the years, a clear, singular delineation will emerge. We remain open to recalibrating if that occurs. But more than likely the historical, technological, behavioral and attitudinal data will show more of a continuum across generations than a threshold. As has been the case in the past, this means that the differences within generations can be just as great as the differences across generations, and the youngest and oldest within a commonly defined cohort may feel more in common with bordering generations than the one to which they are assigned. This is a reminder that generations themselves are inherently diverse and complex groups, not simple caricatures.

In the near term, you will see a number of reports and analyses from the Center that continue to build on our portfolio of generational research. Today, we issued a report looking – for the first time – at how members of Generation Z view some of the key social and political issues facing the nation today and how their views compare with those of older generations. To be sure, the views of this generation are not fully formed and could change considerably as they age and as national and global events intervene. Even so, this early look provides some compelling clues about how Gen Z will help shape the future political landscape.

In the coming weeks, we will be releasing demographic analyses that compare Millennials to previous generations at the same stage in their life cycle to see if the demographic, economic and household dynamics of Millennials continue to stand apart from their predecessors. In addition, we will build on our research on teens’ technology use by exploring the daily lives, aspirations and pressures today’s 13- to 17-year-olds face as they navigate the teenage years.

Yet, we remain cautious about what can be projected onto a generation when they remain so young. Donald Trump may be the first U.S. president most Gen Zers know as they turn 18, and just as the contrast between George W. Bush and Barack Obama shaped the political debate for Millennials, the current political environment may have a similar effect on the attitudes and engagement of Gen Z, though how remains a question. As important as today’s news may seem, it is more than likely that the technologies, debates and events that will shape Generation Z are still yet to be known.

We look forward to spending the next few years studying this generation as it enters adulthood. All the while, we’ll keep in mind that generations are a lens through which to understand societal change, rather than a label with which to oversimplify differences between groups.

Note: This is an update of a post that was originally published March 1, 2018, to announce the Center’s adoption of 1996 as an endpoint to births in the Millennial generation.