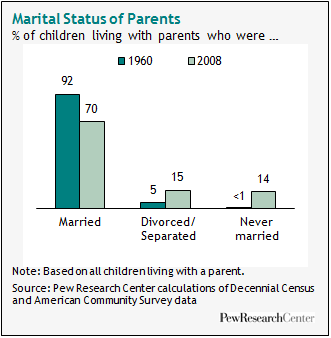

Children in America are growing up in a much more diverse set of living arrangements than they did a half century ago. In 1960, nearly nine-in-ten children under age 18 resided with two married parents (87%); by 2008, that share had dropped to 64%.24 Over the same period, the percentage of children born to unmarried women rose eightfold, from 5% to 41%. Far more children now live with divorced or never-married parents, and the number who live with cohabiting same-sex parents, while still relatively small, has grown over the past two decades.

Americans have embraced these demographic shifts, at least to some extent. Solid majorities say that a single parent, unmarried couple or same-sex couple with children fit their definition of a family, and few express concern about the growing variety in the types of living arrangements.

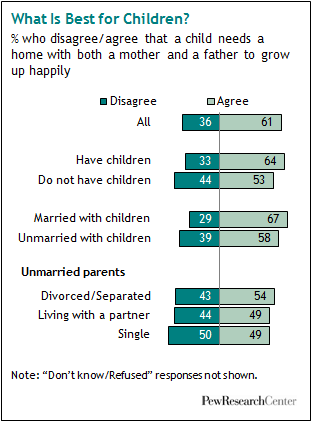

Yet the survey suggests a tension in people’s views. Greater acceptance of the changing nature of the American family coexists with persistent concerns about the effect of non-traditional arrangements on children. More specifically, about six-in-ten (61%) adults believe that a child needs a home with both a father and a mother to grow up happily; about seven-in-ten (69%), say it is bad for society that more single women are raising children without a male partner and majorities generally say that children in less traditional family arrangements face more challenges than their peers.

Views on most of these questions vary according to the family circumstances of the respondent. For example, 64% of parents agree that a child needs a home with both a father and a mother to grow up happily, a view that is shared by just 53% of adults who do not have children.

Parents who are married are especially inclined to believe that a child needs a home with both a father and a mother; 67% say so, compared with 58% of unmarried parents. Among parents who are not married, 54% of those who are divorced or separated and 49% of those who are single or living with a partner agree that children need a home with a mother and a father to grow up happily.25

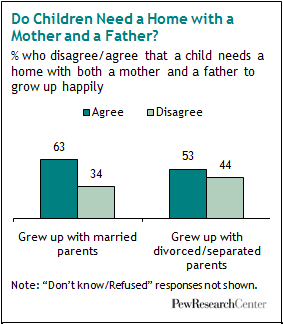

Not surprisingly, the composition of the families in which respondents grew up is related to their views on this question. A narrow majority (53%) of those who say their parents were divorced or separated during most of the time they were growing up agrees that a child needs a home with both a mother and a father; 44% disagree. Of adults whose parents were married while they were growing up, 63% say children need a home with both parents; 34% say they do not.

Demographic Differences in Views of What Is Best for Children

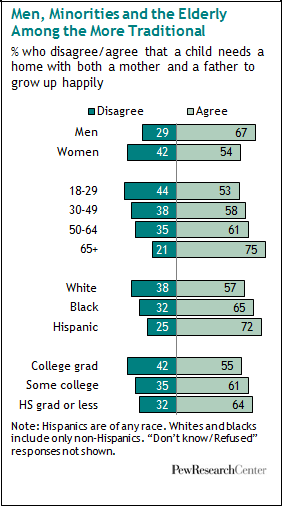

Men are generally more traditional than women in their views of what is best for children. Two-thirds of men agree that a child needs a home with both a mother and a father to grow up happily; just 29% disagree. Among women, opinions are more evenly divided, with 54% saying this type of arrangement is essential and 42% saying it is not.

Opinions about what is best for children also vary somewhat across racial and ethnic lines. Hispanic and black respondents are the most traditional – 72% of Hispanics and 65% of African Americans say a child needs a home with both a mother and a father to grow up happily, compared with 57% of whites.

Racial and ethnic differences in opinions of whether a child needs a home with both a father and a mother are driven, at least in part, by the views of white women, who are nearly evenly divided in their opinion of what is best for children;

50% agree that children need a mother and a father, while 46% disagree. In contrast, clear majorities of white men (65%), black men and women (67% and 63%, respectively) and Hispanic men and women (77% and 68%)believe that children need a home with both parents to grow up happily.

Older respondents are also more likely than younger ones to say that children need a home with both a mother and a father. Three-quarters of those ages 65 or older share this opinion, compared with about six-in-ten of those between ages 50 and 64 (61%) and between ages 30 and 49 (58%) and a slim majority (53%) of those younger than 30.

College graduates are more likely than those without a college degree to be in a traditional household with a spouse and children. Nonetheless, college graduates are less likely than those without a college degree to embrace the traditional view of what is best for children. A 55% majority of those with a college degree agree that children need a home with both a father and a mother to grow up happily, while 42% disagree. By comparison, those with a high school diploma or less are twice as likely to agree (64%) as they are to disagree (32%) that children need a home with both parents.

Societal Impact of Non-Traditional Arrangements

When asked about some specific trends involving children g

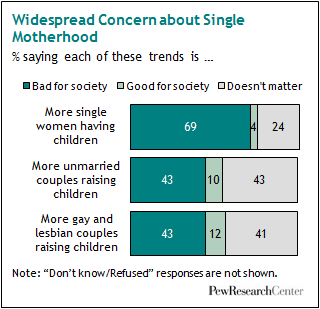

rowing up in non-traditional households, Americans express the most concern about the rise in the number of single women having children without a male partner to help raise them. About seven-in-ten (69%) say it is bad for society that more single women are having children, while just 4% say this is good for society and 24% say it doesn’t make much difference.

Americans are far less concerned about the fact that more unmarried couples and more gay and lesbian couples are raising children, although a substantial minority expresses concerns; 43% say each of these trends is bad for society, but about the same number (43% and 41%, respectively) say it is neither good nor bad. About one-in-ten say it is good that more unmarried couples (10%) and more same-sex couples (12%) are raising children. (These trends are analyzed in more detail in Section 5.)

Challenges for Children

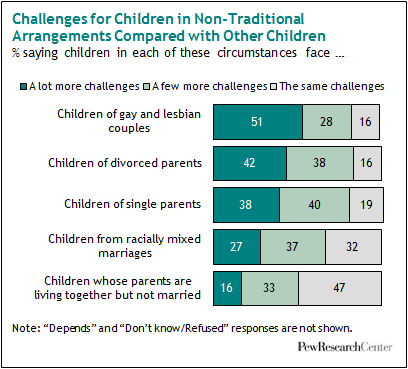

Most of the public believes that children who grow up in less traditional households face more challenges than other children. But not all the non-traditional settings are seen as equally challenging for kids.

Children raised by gay and lesbian couples are seen as facing the most challenges: about half the public (51%) say they face “a lot” more challenges than other children, and an additional 28% say they face “a few” more challenges. Next on the list are children of divorce – 42% say they face a lot more challenges than other children – followed by children of single parents (38% say they face a lot more challenges), children from racially mixed marriages (27%) and children whose parents are living together but not married (16%). Solid majorities say that children in nearly all of these circumstances face at least a few more challenges than other children.

When it comes to children whose parents are living together but not married, however, opinions about whether or not they face more obstacles than their peers are mixed. About half (49%) say children in this circumstance have “a lot more” (16%) or at least “a few more” (33%) challenges to overcome, while 47% say children of cohabiting parents have about the same number of challenges as other children.

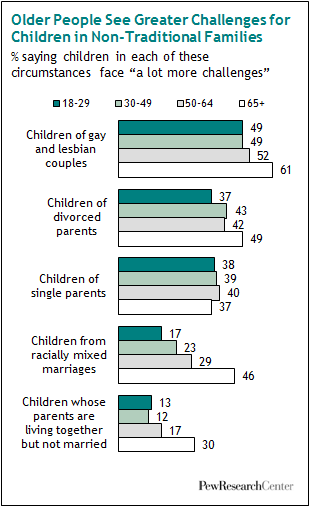

For the most part, opinions about the challenges of children in non-traditional living arrangements do not vary significantly across demographic groups. However, people ages 65 and older are generally more inclined than younger people—especially those younger than 30—to say that children in certain circumstances face a lot more challenges than their peers. This is especially the case when it comes to the children of interracial couples; more than four-in-ten respondents who are 65 or older (46%) say children from racially mixed marriages have considerably more challenges, compared with 29% of those between ages 50 and 64, 23% of those ages 30 to 49 and just 17% of adults younger than 30.

Among parents of young children, those who are married are more likely than those who are not married to say the obstacles children of divorced couples and of single parents face are far greater than those of their peers. Nearly half of married parents with children younger than 18 say children who grow up with divorced parents (47%) or single parents (48%) have a lot more challenges; about one-third of unmarried parents of young children say that is the case.

Finally, the view that children of gay and lesbian parents have considerably more challenges than other children is tied to negative opinions about the impact same-sex parents have on society. Three-quarters of those who say it is bad for society that more gay and lesbian couples are raising children say children of same-sex couples face a lot more challenges than their peers; just 27% of those who say gay and lesbian parents have a positive impact and 34% of those who say it does not make much difference that more same-sex couples are raising children share this opinion.

Parents’ Self-Evaluations

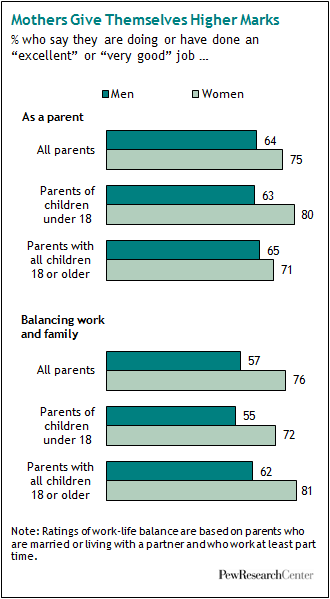

Seven-in-ten parents say they are doing or have done an “excellent” or “very good” job as parents, and those who are married are somewhat more likely than those who are not to say so. Nearly three-quarters of married parents (73%) give themselves high marks, compared with 65% of unmarried parents.

Women are more likely than men to say they are doing an “excellent” or “very good” job as parents, and this is especially true among parents with children younger than 18. Eight-in-ten mothers of young children rate themselves highly, compared with 63% of fathers. The difference is less pronounced among those whose children are all 18 or older; 71% of mothers and 65% of fathers in this group give themselves a strong evaluation.

Mothers of young children, as well as those with adult children, are also far more likely than fathers to say they have done at least a very good job balancing work and family responsibilities. Overall, 66% of parents who are married or cohabiting and who work at least part time give themselves high marks in this regard. About three-quarters of women (76%) rate the job they have done balancing work, their relationship with their spouse or partner, and being a parent as “excellent” or “very good,” compared with 57% of men.

Among those with young children, 83% of working mothers and 75% of mothers who do not work rate themselves as “excellent” or “very good” parents.

Living Arrangements of Children

An analysis of Census Bureau data shows that the percentage of children under age 18 living with divorced or never-married parents has risen sharply over the past half-century. In 1960, about nine-in-ten children residing with a parent lived with married parents (92%); 5% had parents who were divorced or separated, and less than 1% lived with parents who had never been married. By 2008, seven-in-ten minor children who lived with a parent were residing with married parents, while about three-in-ten had parents who were divorced or separated (15%) or who had never been married (14%).26

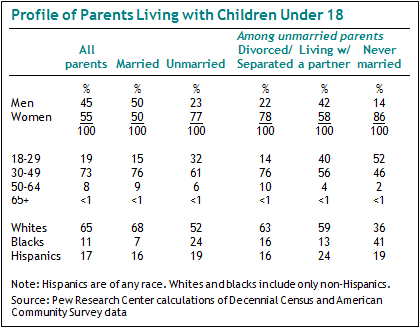

Women account for 77% of unmarried parents living with children under the age of 18; 86% of parents who live with their minor children and have never been married and are not living with a partner are mothers, as are 78% of those who are divorced or separated.

A disproportionate percentage of single parents are black. While 11% of all parents who are living with children under 18 are African American, 41% of those who have never been married and do not have a live-in partner are black; 36% of single parents are white and 19% are Hispanic.

Single parents and those who are living with a partner tend to be younger than divorced or married parents. About half of parents who have never been married and are not currently living with a partner (52%) and 40% of cohabiting parents are younger than 30. In contrast, just 15% of married parents and 14% of divorced parents are in this age group.

Many Had Children before Marriage

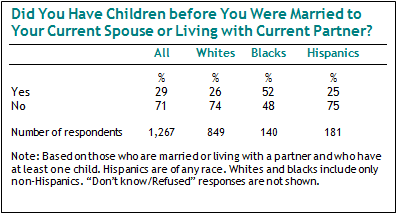

To complement Census Bureau data, the survey asks parents who are married or cohabiting whether any of their children were born before they were married to their current spouse or living with their current partner. Nearly a third (29%) say that is the case, including 63% of cohabiting parents who say they had children before they started living with their partner; 25% of married parents had at least one child before they married their current spouse.

Black parents who are married or cohabiting are particularly likely to have had children before they were married to their current spouse or living with their current partner; about half (52%) say that is the case, compared with just about a quarter of married or cohabiting white and Hispanic parents (26% and 25%, respectively).

Living Arrangements of Parents and Children

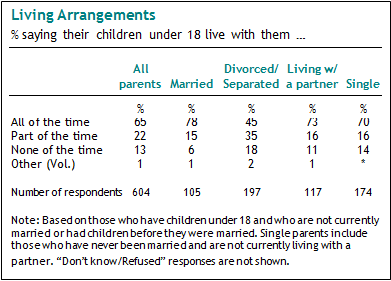

Of the parents surveyed who have children under the age of 18 and who are not married or had children before they were married, about two-thirds (65%) say their children live with them all of the time, 22% say the children live with them part of the time and 13% say the children don’t live in their household.

Divorced parents are especially likely to share custody of their young children; fewer than half (45%) say their children under the age of 18 live with them all of the time, while 35% say the children live with them part of the time and 18% say their children don’t live in their household. By comparison, 78% of married parents who had children before they were married, 73% of cohabiting parents who had children before they were living with their current partner and 70% of single parents say their children live with them all of the time.

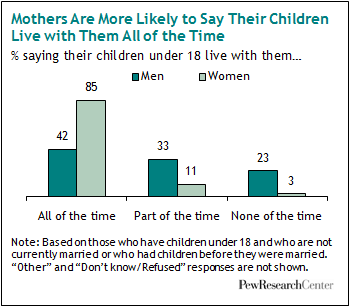

Women are twice as likely as men to have their young children living with them all of the time; more than eight-in-ten mothers of young children who are not married or who had children before they were married say that is the case (85%), compared with 42% of fathers. One-third of fathers who are not currently married or who had children before they were married say their children live with them some of the time, and a considerable percentage (23%) say their children don’t ever live in their household.

Most Who Do Not Have Children Want Them

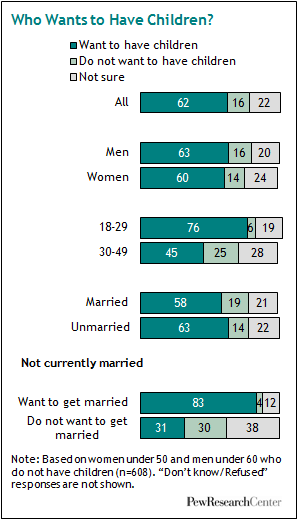

Among women younger than 50 and men younger than 60 who do not have children, most (62%) say they want to have children someday. Those who are younger than 30 are particularly likely to say that is the case; 76% of those in that age group who do not have children hope to have them in the future, compared with fewer than half (45%) of those between the ages of 30 and 49.

Childless respondents who are currently married and those who are not are about equally likely to say they want to have children someday (58% and 63%, respectively). Among people who are not married, however, those who hope to get married are far more likely than those who do not want to get married to say they want kids. About eight-in-ten of those who want to get married want to have kids (83%); among those who do not want to get married, just 31% hope to have children someday, while 30% say they do not want children and 38% are not sure.