Fatherhood and Marriage

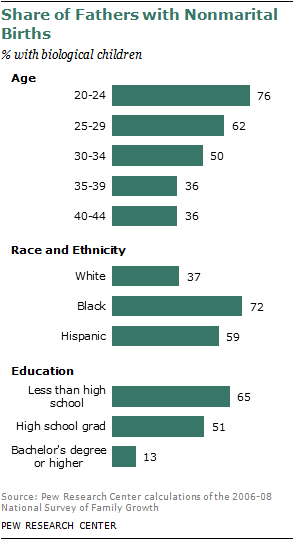

Nearly half (46%) of men ages 15 to 44 with biological children report that at least one of their children was born outside of marriage,5 and 31% report that all of their children were born outside of marriage. In contrast, 69% report that they have had at least one of their children within a marriage.

Among young and middle-aged men, the likelihood of having a child out of wedlock varies by cohort. Among biological fathers ages 20 to 24, more than three-fourths (76%) have had a child out of wedlock, while this share drops to 36% for fathers ages 35 to 44.

There are notable differences by race and ethnicity, as well. Some 37% of white biological dads have had at least one child out of wedlock, while 77% have had a birth within a marriage. Black and Hispanic fathers are much more likely to report having had a nonmarital birth. Among black men, 72% have had a child out of wedlock, and 48% have had one in marriage; and among Hispanic men, 59% have had a birth out of wedlock, and 58% have had a birth within a marriage.

Biological fathers with high levels of education are far less likely to have had a child out of wedlock than their less-educated counterparts. Only 13% of those with at least a bachelor’s degree report a nonmarital birth. In comparison, almost two-thirds (65%) of those who never completed high school have a child out of wedlock, as do over half (51%) of those whose highest educational attainment is a high school diploma.

Just over half (55%) of men with biological children are married to the biological mother of all of those children. An additional 7% of biological fathers are cohabiting with the mother of their children.

Fathers under age 30 are less likely than older fathers to be married to the mother of their children. Some 26% of dads ages 20-24 report as much, as do 47% of dads ages 25-29. In comparison, 58% of fathers ages 40-44 are married to the mother of their children. While they are far less likely than their older counterparts to be married to the mother of their children, more than half of fathers ages 20-24 (53%) and 25-29 (62%) are still in a relationship—marital or cohabiting—with the mother of their children.

Black biological fathers are far less likely than white biological fathers to be married to the mother of their children. Some 36% of blacks are in this situation, compared with 59% of whites. Among Hispanic biological fathers, this share is 50%.

Education is closely linked with the likelihood of a biological father’s being married to the mother of his children. Among fathers with less than a high school diploma, 40% are married to their children’s mother. The share rises to 50% for fathers who have a high school diploma. For fathers with at least a bachelor’s degree, the share married to the mother of their children jumps to 83%.

Fathers and their Children

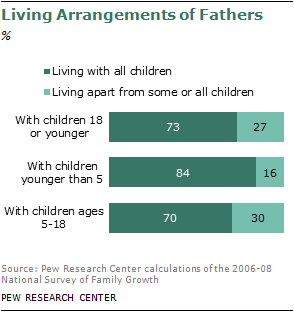

Overall, 73% of men with children 18 or younger report that they live with those children at least part of the time (i.e., they “co-reside”).6 Conversely, more than one-fourth of fathers (27%) are living apart from at least one of their children: 16% are living apart from all of their children, and 11% are living apart from some of their children.

Among fathers of children ages 5-18, 70% are living with all of those children—meaning that three-in-ten are living apart from at least one of their children. Rates of co-residence with younger children are generally higher, even so almost one-in-six (16%) fathers are living apart from at least one of their children under age 5.

There is little historical trend data directly measuring the share of fathers co-residing with their children. However, the U.S. Census Bureau offers a related measure—the share of children living with, or living apart from, each of their parents. In 1960, 89% of minor children were living with their fathers, and 96% of children were living with their mothers. In other words, 11% of children were living apart from their fathers, and 4% were living apart from their mothers. Fifty years later, the share of children living with their fathers fell to 73%, meaning that 27% (some 20.3 million) were living apart from their fathers. In comparison, 92% of minors were living with their mothers, and 8% were living apart from them (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

The increased share of children living apart from their fathers is due at least in part to the decline in the share of children living in two-parent households in general, which in turn is related to a decline in marriage rates. While 72% of the adult population was married in 1960, that share dropped to 52% by 2008. And while 87% of children ages 17 and younger were living with two married parents in 1960, in 2008 the share dropped to 64%, with an additional 6% of children living with two cohabiting parents (Pew Social and Demographic Trends, 2010). Multi-partner fertility also contributes to complex family structures and to the large share of fathers living apart from at least some of their children. Research indicates that about 17% of biological fathers have fathered children with more than one woman.7

A father’s age is not linked to the likelihood that he is living apart from any of his children 18 or younger. Some 31% of dads ages 20-24 are living apart from at least one of their children, compared with 25% of those ages 40-44. When the sample is limited to fathers of children younger than 5, though, some age differences do emerge, with fathers in their twenties being more likely than older fathers to live apart from their young children. For instance, 27% of fathers ages 20-24 are living apart from at least one of their young children, compared with 6% of fathers ages 40-44.

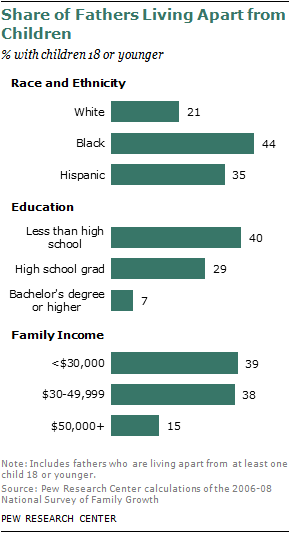

Race and ethnicity are strongly associated with the likelihood that a father will live apart from at least one of his children. While about one-fifth (21%) of white fathers live apart from at least one of their children, this number rises to 35% among Hispanic fathers, and 44% among African American fathers. This pattern persists when examining fathers of children younger than 5, with 10% of white fathers living apart from at least one of their young children, compared with 24% of Hispanic fathers and 32% of African American fathers.

Four-in-ten fathers lacking a high school diploma live apart from at least one of their children. Among high school graduates, the share decreases to 29%, and among college graduates, it drops to 7%.

And while three-in-ten (29%) fathers with less than a high school diploma live apart from at least one of their children under age 5, the share declines to 17% for high school graduates, and 4% for fathers with a bachelor’s degree or more.

Fathers with higher family incomes are much less likely to be living apart from any of their children than are those with lower incomes. Some 15% of fathers with annual family incomes of $50,000 or more live apart from a child, compared with 39% of those with incomes below $30,000 and 38% of those with incomes of $30,000 to $49,999. The pattern holds true when looking only at fathers of young children. Just 5% of fathers with family incomes of $50,000 or more are living away from a child less than 5 years of age. In comparison, some 29% of dads with family incomes of less than $30,000 live apart from a child, as do 24% of dads with incomes of $30,000 to $49,999.

Absent Fathers: Involvement from a Distance?

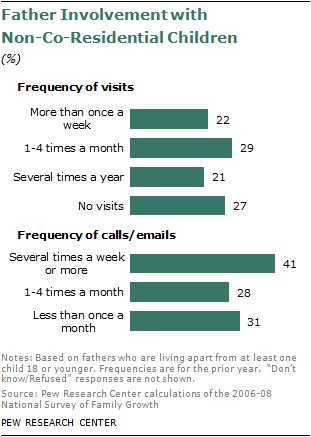

While more than one-quarter (27%) of fathers are living apart from their children 18 or younger, there is a huge variation in the type of involvement that these “non-co-resident” fathers have with their children. On one end of the spectrum, almost one-fifth (18%) report only occasional contacts with their children, and no visits in over a year. At the other end of the spectrum are the 14% of fathers who live apart from their children but report still seeing them several times a week, and talking with or emailing them several times a week, as well.

Among dads who are not living with their children, less than one-fourth (22%) report that they visited with their children more than once a week on average over the past year. Some 29% saw their children 1 to 4 times a month, and 21% saw them several times in the past year. More than one-fourth of non-co-residential dads (27%) report that they did not see their non-co-residential children at all in the past year.

There are no age differences in the likelihood of a father’s seeing his non-co-resident child at least once a month.

Hispanic fathers living apart from their children are much less likely than others to see those children monthly or more. Roughly one-third (32%) do so, compared with 59% of whites and 67% of blacks.

Some 41% of non-co-resident fathers lacking a high school diploma saw their children at least once a month, and this share rises to 57% among fathers with a high school diploma. In terms of income, though, there were no major differences—fathers with family incomes below $30,000 who were living apart from their children were statistically as likely as fathers with higher incomes to visit with those children at least once a month.

While just over two-in-ten fathers saw their non-co-resident children several times a week during the prior year, almost double that share (41%) report that they communicated with their children via phone or email several times a week during that same time period. On the other end of the spectrum, a sizable minority—31%—report that they communicated with their non-co-resident children less than once a month. An additional 28% emailed or called their children one to four times a month during the prior year.

There are no race or ethnic differences in the likelihood of having email or phone contact with a non-co-resident child several times a week or more.

Three-in-ten (31%) fathers with less than a high school diploma report communicating with their children several times a week or more in the past year. This is a lower share than the 48% of fathers with a high school diploma who report the same.

Fathers with low family incomes were less likely than higher income fathers to contact their non-co-residential children at least several times a week. One-third (31%) of fathers with annual family incomes of less than $30,000 report having had contact via phone or email with their children at least several times a week in the prior year. In comparison, this share is 45% for those with incomes of $30,000 to $49,999 and 49% for those with family incomes of $50,000 or more.

Time Spent with Children

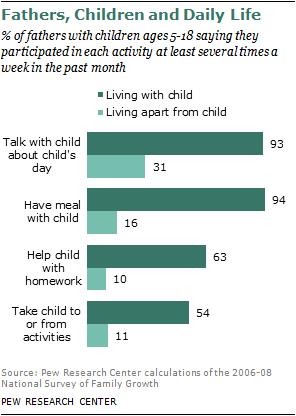

When it comes to spending time with children, co-residence matters—a lot. In fact, whether a father lives with his children is more directly associated with his day-to-day involvement with them in the prior four weeks than his race, ethnicity, age, education or income. The vast majority of fathers who live with their children report regular involvement in their routine care, while the story is much more mixed for fathers who live apart from their children.

Talking with children about their day: More than nine-in-ten (93%) fathers who live with their children ages 5-18 report that they talked with their children about things that happened in their children’s day several times a week on average in the four weeks prior to the interview. Three-in-ten (31%) fathers living apart from their children report the same. The plurality of non-co-resident fathers (44%) report that they hadn’t talked to their children about their day at all in the previous four weeks. One-fourth (25%) report doing so occasionally, up to about once a week.

Co-resident fathers ages 25-29 are less likely to talk with their children about their day at least several times a week than are those ages 35-39 (89% vs. 96%), but otherwise no significant age differences emerge.

The only other notable difference among fathers who reside with their children occurs by educational level. While 89% of co-resident fathers with less than a high school diploma talked with their children several times a week about their day, this share rises to 97% among college graduates. For high school graduates, the share is 93%.

Among fathers living apart from their children, there are some differences by race and ethnicity in the likelihood of talking with their children several times a week about their day. Blacks are far more likely to do so than their white or Hispanic counterparts. While almost half (49%) of blacks talk with their children several times a week about their day, the share of Hispanics who do so is 22%, and of whites, 30%.

Sharing meals with children: When it comes to sharing meals with their children, the vast majority of co-resident dads report doing so often. Fully 94% report eating with their children ages 5-18 several times a week in the four weeks prior to being interviewed. This is far higher than the 16% of non-co-resident fathers who share several meals a week with their children. In fact, the majority (57%) of fathers who live apart from their children report sharing no meals with their children ages 5-18 in the last four weeks, and just over one-fourth (26%) ate with their children sometimes, but no more than once a week.

Among fathers who live with their children, the likelihood of sharing several meals a week with children ages 5-18 is quite consistent across almost all categories. The only exception occurs in terms of education—high school graduates were less likely than those with a bachelor’s degree to eat several times a week with their children ages 5 to 18. Some 92% of high school graduates did so, compared with 98% of those with a bachelor’s degree. The share of fathers with less than a high school diploma who did so is 94%.

There are no differences among subgroups of non-co-resident fathers in this measure.

Helping children with homework: More than six-in-ten (63%) fathers who live with their children ages 5-18 report that they helped those children with homework or checked with their children about their homework several times a week in the four weeks prior to being interviewed. An additional 22% helped or checked at least sometime (up to once a week), and 15% did not inquire about or help with homework at all. In contrast, one-in-ten (10%) non-co-residential fathers helped with or inquired about the homework of their children at least several times a week, 15% helped out or inquired at least sometime, and fully three-fourths (75%) did not help or check on homework in the four weeks preceding the interview.

Taking children to and from activities: More than half (54%) of fathers report that they took their co-resident children ages 5-18 to and from activities several times a week or more in the four weeks prior to being surveyed. Some 31% did so up to once a week, while 15% report not doing so at all. Among the dads living apart from their children, only about one-in-ten (11%) transported their children several times a week, compared with 17% who did so up to once a week, and fully 72% who didn’t transport their child at all in the four weeks preceding the survey.

In terms of subgroup differences in the likelihood of transporting children several times a week, education emerges as an important indicator for fathers who live with their children. Those with a bachelor’s degree were far more likely to do so (65%) than were those lacking a high school diploma (49%) or those with only a high school diploma (51%).8

Among fathers not living with their children, there were no subgroup differences in the likelihood of chauffeuring children several times a week or more in the four weeks prior to being interviewed.

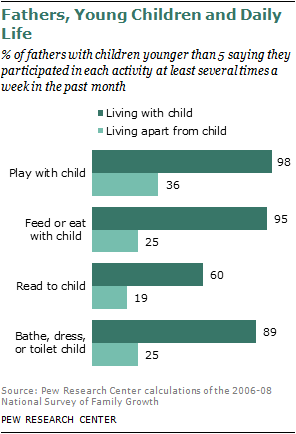

Playing with young children: Fathers of children younger than 5 years of age were asked how often they played with their children in the four weeks prior to being interviewed. Almost all fathers living with their young children (98%) played with those children at least several times a week. Among fathers not living with their young children, more than one-third (36%) report the same. About one-fifth of the non-co-resident fathers (21%) played with their young children at least some, and 43% did not play with their young children at all.9

Sharing meals or feeding young children: The vast majority (95%) of fathers living with their children under the age of 5 shared meals with or fed those children several times a week or more over the four-week period prior to being interviewed. In contrast, this share was 25% among fathers living apart from their children. The plurality (48%) of non-co-resident fathers of young children shared no meals with their children, and just over one-fourth (26%) ate with or fed their young children at least occasionally during that period.

There are no differences among co-resident fathers in the likelihood of feeding or eating with their young children.

Reading to young children: Six-in-ten (60%) co-resident fathers report reading to their children under age 5 at least several times a week in the four weeks prior to being interviewed. One-fourth (25%) did so occasionally, and 15% didn’t read to their children at all. Almost two-in-ten (19%) non-co-resident fathers read to their young children several times a week or more, while 22% did so occasionally, and 59% didn’t read to their children at all.

Unlike most of the preceding measures, there are a number of subgroup differences among co-resident fathers when it comes to reading to their children.

Less than half (45%) of co-resident Hispanic fathers read to their children ages less than 5 several times a week or more, compared with 65% of white co-resident dads. Some 62% of black co-resident fathers read to their young children several times a week or more in the four weeks preceding the survey.

Co-resident fathers with a bachelor’s degree were far more likely than others to read to their young children several times a week or more. More than three-fourths (76%) did so, compared with 48% of those with less than a high school diploma and 57% of those with a high school diploma.

Economic circumstances were also linked to the likelihood of reading often to a young child. While more than two-thirds (68%) of co-resident fathers with family incomes of $50,000 or more read to their children at least several times a week, some 54% of fathers with annual family incomes of less than $30,000 did so, and half (50%) of fathers with annual family incomes of $30,000 to $49,999 did so.

Bathing, dressing or toileting young children: Almost nine-in-ten (89%) fathers who live with their young children report that they helped in bathing, dressing or toileting them several times a week in the four weeks preceding the survey. In contrast, one-fourth (25%) of fathers living apart from their young children report the same. More than half (54%) of non-co-resident fathers report no participation in these activities in the prior four weeks, and 21% report occasionally being involved in these activities during this period.

There are no subgroup differences in the likelihood of bathing, dressing, or toileting young children among co-resident fathers in the four weeks prior to being surveyed.

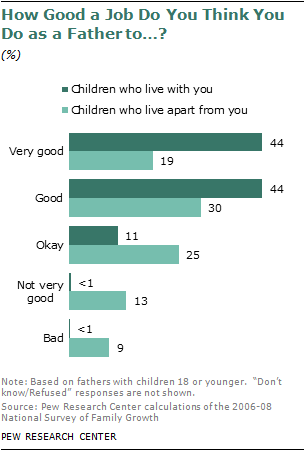

How Good a Father Are You?

All men with children 18 or younger were asked, “How good a job do you think you do as a father?” The question was asked separately in reference to co-resident and non-co-resident children, and results differ markedly for each group.

Almost 9-in-10 (88%) fathers who live with their children rate themselves as doing a good or very good job, while just under half (49%) of non-co-resident fathers evaluate themselves similarly. Some 44% of fathers think they do a very good job with co-resident children, and another 44% think they do a good job. Some 11% think they do an “okay” job. In contrast, only 19% of fathers report that they are very good parents to their non-co-residential children, while 30% think they are a good parent. One-fourth (25%) think they are doing an okay job parenting non-co-residential children, and 22% think they are doing a not very good or bad job.

Among co-resident fathers, there are no subgroup differences in the likelihood of rating one’s parenting as either good or very good. Among non-co-resident fathers, the only significant difference emerges on age—fathers ages 25-29 are more likely to rate themselves as good or very good than are fathers ages 40-44 (63% vs. 41%).

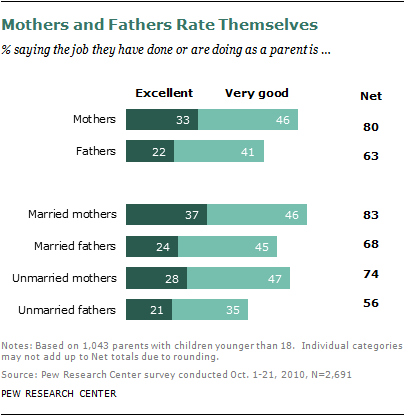

How Parenting Self-Evaluations Differ Between Mothers and Fathers

In October of 2010, the Pew Research Center conducted a nationwide survey of 2,691 adults regarding their attitudes about and experiences with family. According to that survey, the majority (71%) of parents with children under age 18 say that they are doing an “excellent” or “very good” job as parents.

However, fathers give themselves lower marks than mothers: 63% of fathers with children under age 18 think that they are doing an “excellent” or “very good” job as parents, compared with 80% of mothers with similarly aged children.

Married mothers are the group that rates their parenting the highest. More than eight-in-ten (83%) rate their parenting as either “excellent” or “very good.” On the other end of the spectrum, unmarried fathers give themselves the lowest rating: some 56% think that they are doing an “excellent” or “very good” job as parents.

Future Birth Intentions and Desires

Data from the NSFG indicate that 53% of males ages 15-44 have no children, and among men ages 40-44, that share is 20%.10

The survey asked two separate questions about future fertility: It inquired “If it were possible, would you want to have (more) children?” and it also asked whether someone intended to have (more) children. Overall 87% of men ages 15-44 who had no biological or adopted children (and who did not have a pregnant spouse or partner at the time of survey) wanted to have children, but only about 82% of those males intended to have children. The discrepancy between these two statistics points to the fact that about 6% of childless men wanted children but were not expecting to ever have them.

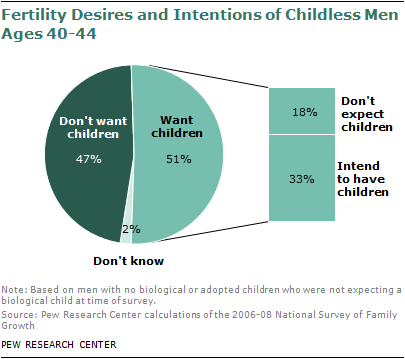

Among men ages 20-24, the share of those who are childless who want children but aren’t expecting to have them is very low (3%). Among childless men ages 40-44, about half (51%) reported that they want children, however, some 18% weren’t expecting to ever have children, despite their desire to do so. In comparison, 20% of childless women ages 40-44 wanted children but weren’t expecting to ever have them.

Across other major demographic characteristics, there is little variation among childless men in the intention for children, desire for children or unmet desire for parenthood.

Over one-fourth (27%) of childless men say that it would bother them a great deal if they never have children. Roughly one-third (32%) report that it would bother them some, 19% say it would bother them a little, and one-fifth (21%) report that it wouldn’t bother them at all if they never had children. Among childless women, 36% would be bothered a great deal if they never had children, 32% would be bothered some, 14% would be bothered a little, and 17% wouldn’t be bothered at all.

Younger males are more likely than their older counterparts to report that they would be bothered a great deal by childlessness—28% of 15- to 19-year-olds say as much, as do 35% of those ages 20-24. In contrast, only 16% of men ages 35-39 say that they would be bothered a great deal by not having children, and 5% of those 40-44 say the same.

There are no other notable subgroup variations.