As the United States marks the 10th anniversary of the longest period of sustained warfare in its history, the vast majority of veterans of the post-9/11 era are proud of their military service and say it has helped them mature as human beings. More than eight-in-ten would advise a young person close to them to join the military.

However, only a third (34%) of these veterans say that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have both been worth fighting. And about half (51%) say that relying too much on military force to defeat terrorism creates hatred that leads to more terrorism.

The ambivalence that many post-9/11 veterans feel about their military mission has a parallel in the mixture of benefits and burdens they report having experienced since their return to civilian life.

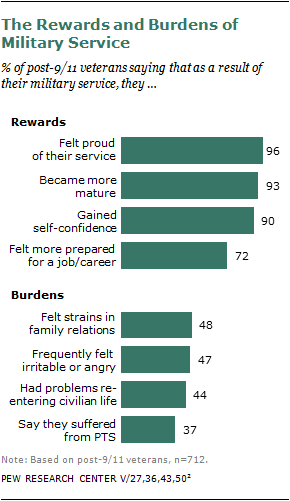

Nine-in-ten say that serving in the military has given them self-confidence; helped them mature; and taught them how to work with other people. Seven-in-ten say it has helped them prepare for a post-military career.2

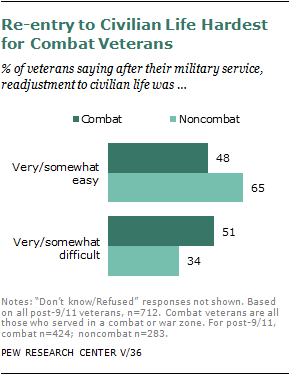

But a relatively large share of modern-era veterans—44%—report that they have had difficulties readjusting to civilian life. Just 25% of veterans who served on active duty in earlier eras report that they had these difficulties, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of a nationally representative sample of 1,853 veterans, including 712 who served on active duty in the post-9/11 era.3

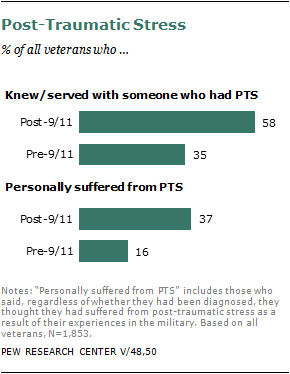

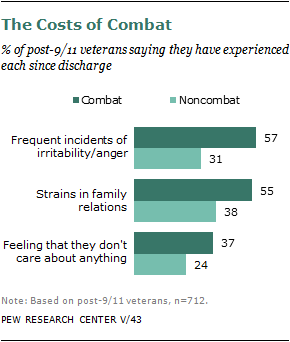

Many of the homecoming challenges faced by this era’s returning veterans have an emotional or psychological component, the survey finds. Nearly half (47%) say that, since their discharge, they have experienced frequent bouts of irritability or outbursts of anger. About half (48%) say their family relations have been strained. A third (32%) say they have sometimes felt that they didn’t care about anything. Nearly four-in-ten (37%) say that, whether or not they have been officially diagnosed, they believe they have suffered from post-traumatic stress.

A Military-Civilian Gap

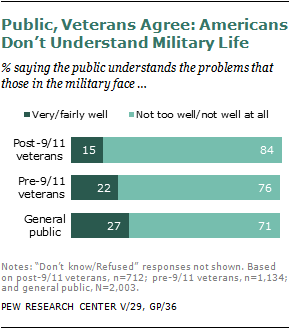

The Pew Research survey also finds that 84% of these modern-era veterans say that the American public has little or no understanding of the problems that those in the military face. The public shares in that assessment, albeit by a less lopsided majority—71%, according to a companion Pew Research survey conducted among a nationally representative sample of 2,003 American adults ages 18 and older.

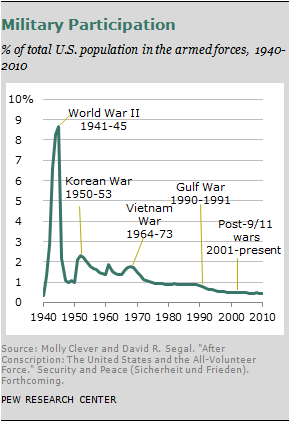

Since 1973, there has been no military draft. So unlike other U.S. wars waged in the past century, the post-9/11 conflicts have been fought exclusively by a professional military and enlisted volunteers. During this decade of sustained warfare, only about 0.5% of the American public has been on active duty at any given time. (At the height of World War II, the comparable figure was nearly 9%.) As a result of the relatively small size of the modern military, most of those who served during the past decade were deployed more than once, and 60% were deployed to a combat zone.

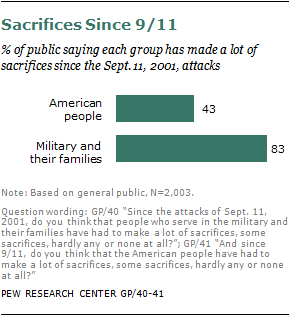

The American public is well aware that the sacrifices the nation was called upon to make following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, have not been borne evenly across the military-civilian divide. More than eight-in-ten Americans (83%) say that members of the military and their families have had to make “a lot of sacrifices,” while just 43% say the same about the public as a whole.

But even among those who say the military’s sacrifices have been greater than the public’s, seven-in-ten say they see nothing unfair in this disparity. Rather, they say, it’s “just part of being in the military.”

For Better and Worse

What has it meant to serve in the military during the post-9/11 era? Compared with their predecessors of a generation or two ago, those who serve in the modern military are fewer, older, better educated and more likely to be married. A greater share is women and minorities.

In all, more than 6,200 American troops have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan during the past decade, and more than 46,000 have been wounded.4 Tragic as these losses are, the fatality rate in the military during the post-9/11 wars is not high when measured against the human toll from other wars (see Chapter 6)—a testament to changing military tactics and advances in battlefield medical care.

Overall, about one-in-six post-9/11 veterans (16%) report they were seriously injured while serving in the military, and most of these injuries were combat-related. And about half (47%) say they know and served with someone who was killed while in the military, not significantly different from the share of pre-9/11 veterans (43%) who say the same.

But there is one front where this generation’s warriors appear to have been hit harder than their predecessors: the home front. As already noted, many more post-9/11 veterans (44%) than pre-9/11 veterans (25%) say that their readjustment to civilian life has been difficult.

Also, a greater share of post-9/11 veterans than pre-9/11 veterans report that they are carrying psychological and emotional scars arising from their time in the military. Some 37% of all post-9/11 veterans (and 49% of post-9/11 veterans who served in a combat zone) say they have suffered from post-traumatic stress. Among pre-9/11 veterans, the comparable figures are 16% for all and 32% for those who saw combat. Post-9/11 veterans are also much more likely than those who served in earlier times to say they know someone who suffered from PTS.5

Among post-9/11 veterans who were married during the time they served, about half (48%) say their deployments had a negative impact on their relationship with their spouse. Among veterans in previous eras who were married while they served, just 34% say the same.

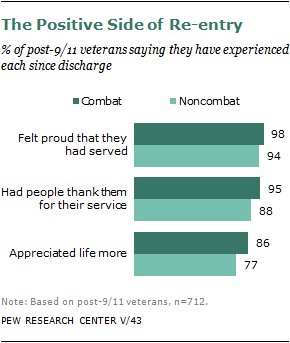

But for this generation of homecoming veterans, the litany of problems tells only part of the story. The other part—the positive part—is also quite compelling.

Post-9/11 veterans are proud of their service (96%), appreciate life more (82%) and believe that their military service has helped them get ahead in life (74%). Large majorities say that serving in the military has been either very or fairly useful in helping them become more mature (93%); gain self-confidence (90%); learn to work with other people (90%); and prepare for a job or career (72%). Some 92% say that since they got out of the service, someone has thanked them for serving. On all these measures, there are few if any differences between pre- and post-9/11 veterans.

Patriotic, Proud, Respected

A majority of the nation’s post-9/11 veterans (61%) consider themselves more patriotic than most other Americans; just 5% say they are less patriotic (the remainder say they are about as patriotic as everyone else). When the public is asked the same question, 37% say they are more patriotic and 10% say less.

Modern-era veterans would make good military recruiters. Some 82% say they would advise a young person close to them to enlist in the military; 74% of pre-9/11 veterans say the same. The general public is much more ambivalent. Despite their great admiration for the troops, just 48% of members of the public say they would advise a young person to join the military; 41% say they would not.

Post-9/11 veterans are more likely than the general public to say the military operates efficiently (67% vs. 58%). Most (54%) say that people generally get ahead in the military based on their hard work and ability; the share of pre-9/11 veterans who feel this way is even larger—63%.

The post-9/11 veterans served at a time when the military has become the most respected institution in the nation (see Chapter 5) and veterans from earlier eras are mindful of this shift in public opinion. Among veterans who served before 9/11, 70% say that the American public has more respect for those who serve in the military now than it did at the time of their own service.

Judging the Wars They Fought

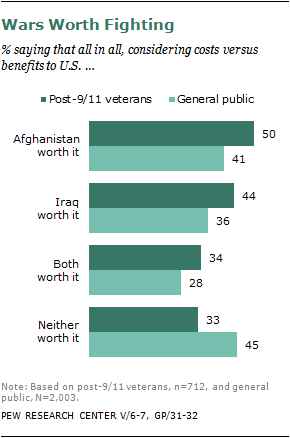

Veterans who have served in the post-9/11 era have a more positive view than the general public about the overall worth of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and the tactics the military has used to wage them. Even so, only one-third (34%) of these recent veterans say that both wars have been worth fighting; nearly as many (33%) say neither conflict has been worth the costs.

Looking at each conflict individually, 50% of post-9/11 veterans say the decade-old war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting, while 44% view the 8½-year-old conflict in Iraq the same way. In comparison, just 41% of the public says the conflict in Afghanistan has been worth the costs and just 36% hold a similarly approving view of Iraq.

About half of post-9/11 veterans who served in combat say the war in Afghanistan has been worth fighting (54%), and nearly as many (47%) view the war in Iraq the same way.

Understanding the Mission

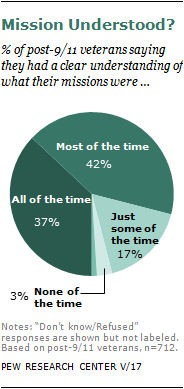

Most post-9/11 veterans say they understood the missions they were assigned, though they are less likely than veterans of earlier eras to say they always understood their assignments. Majorities also view the military as an efficient, meritocratic organization where hard work and ability are rewarded.

Nearly eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans say they understood their missions “all of the time” (37%) or “most of the time” (42%). One-in-five (20%) say they understood their assignments just some or none of the time. However, post-9/11 veterans are less likely than those who served in earlier eras to say they clearly understood their assignments “all of the time” (37% vs. 50%).

Overall, post-9/11 veterans are more likely than the general public to say the military operates efficiently (67% vs. 58%). A majority (54%) of post-9/11 veterans also think people generally get ahead in the military based on their hard work and ability, a proportion that rises to 63% among veterans who served before 9/11. By comparison, Americans overall are split 48%-48% on whether people generally get ahead in their job or career on the basis of hard work and ability.

The Public’s Perspective

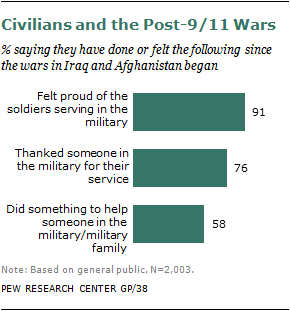

When asked to make judgments about the nation’s military in the post-9/11 era, the public draws a sharp distinction between the troops—for whom they express pride and gratitude—and the wars—about which they express increasing levels of disapproval, indifference and fatigue.

First, the positives. Since the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq began, 91% of the public say they have felt proud of the soldiers; 76% say they have personally thanked someone in the military for their service, and 58% say they’ve done something to help someone in the military or their family.

At the same time, a third (34%) say they have felt ashamed of something the military had done in Afghanistan or Iraq. And 50% say they have felt that those wars have made little difference in their life. Other Pew Research surveys (see Chapter 5) suggest that some of this indifference is the result of public fatigue with a 10-year conflict that many in the public doubt will produce a clear victory. And some is the byproduct of a growing national preoccupation with the sour economy at home. The result: Only about a quarter of Americans now say they are paying close attention to the wars, well below the levels of interest recorded by Pew Research surveys earlier in the decade.

With fading interest has come fading support. At the outset, each of the two wars enjoyed widespread public approval. But in this latest Pew Research survey, a majority (57%) of the public says the war in Iraq has not been worth fighting and nearly as great a share (52%) says Afghanistan has not been worth the cost.

Drones, Nation Building and the Draft

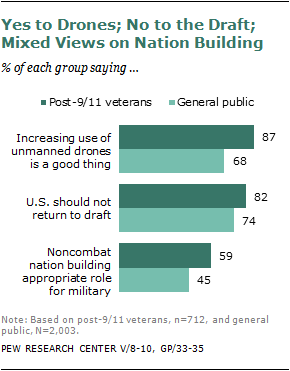

Almost all post-9/11 veterans approve of one new form of warfare that has come to prominence in the past decade: the use of unmanned aircraft known as “drones” for targeted aerial attacks on individual targets in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere.

Nearly nine-in-ten—87%—say the increased use of drones by the military is a good thing. The public agrees, but by a less lopsided majority—68% approve the use of drones.

Veterans and the public are significantly less supportive of noncombat military “nation-building” missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. These assignments, designed to rebuild and strengthen key social, political and economic institutions, are viewed as “appropriate” roles for the military by 59% of all post-9/11 veterans but only 45% of the public and 45% of veterans who served before the terrorist attacks.

Both the public and veterans oppose bringing back the draft. More than two-thirds of all veterans (68%) and a larger share of the public (74%) oppose reinstating conscription. Among veterans, opposition to the draft is highest among those who have served since 9/11 and lowest among those who served before the draft was abolished in 1973 (82% vs. 61%).

The Changing Profile of the Military

New missions, new tactics, new technology and an all-volunteer fighting force are not the only reasons that the modern military is different from previous generations of armed forces.

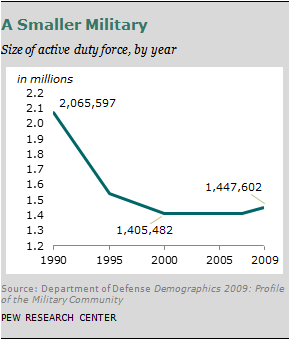

Today’s military is roughly 30% smaller than it was 20 years ago, when slightly more than 2 million men and women served on active duty. The military downsized at the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s and again in the aftermath of the Gulf War in 1990-91. The 9/11 terrorist attacks and the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq halted the decline, and since 2000 the overall size of the military has increased by about 40,000, to approximately 1.44 million.

The post-9/11 military is older and more diverse than the force that served a generation or two ago. Proportionately fewer high school dropouts and more college graduates, women and minorities fill the ranks.

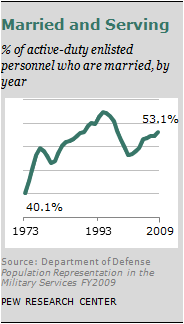

A service member today also is more likely to be married—about 53% are husbands or wives—and more likely to be married to someone in the military than in 2000. During the past 10 years, the annual divorce rate among married active-duty enlisted personnel has also increased, from 2.9% in 2000 to 4.0% in 2009.

Even as a higher share of the military personnel is made up of married people with families, their deployments away from home have increased in frequency and length. More than eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (84%) say they were deployed at least once while serving—and nearly four-in-ten (38%) say they have been deployed three times or more. Among veterans who were married while they were on active duty, nearly half say deployment had a negative impact on their relationship with their spouse (48%) and nearly as many parents reported that their relationship with their children suffered when they were away (44%).

But veterans say that balancing these problems are the benefits and rewards of deployment: better pay and allowances while on deployment, improved chances for advancement and the satisfaction that they were doing important work for their country.

Politics and Religion

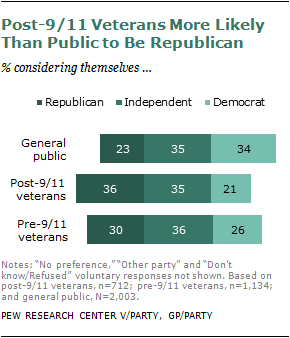

Post-9/11 veterans are more likely than adults overall to identify with the Republican Party and to disapprove of the job that President Obama is doing as commander in chief.

According to the Pew Research surveys, more than a third of post-9/11 veterans (36%) say they are Republicans, compared with 23% of the general public. Equal shares of these veterans and the public call themselves independents (35%), while 21% of veterans and 34% of the public describe themselves as Democrats.

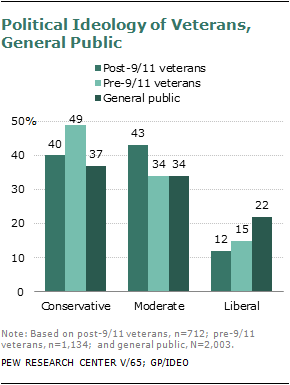

Overall, nearly half of all veterans (48%) say they are politically conservative, compared with 37% of the public. Pre-9/11 veterans are more conservative than those who have served since the terrorist attacks (49% vs. 40%). At the same time, those who served after the terrorist attacks are more inclined than pre-9/11 veterans to say they are political moderates (43% vs. 34%).

These partisan and ideological leanings largely explain why veterans are more likely than the general public to disapprove of how Obama, a Democrat, is handling his job as the nation’s commander in chief.

Among the general public, 53% approve of Obama’s job performance as commander in chief and 39% disapprove. The president fares worse among veterans: Nearly half of post-9/11 veterans (47%) and a slightly larger share of those who served before the terrorist attacks (51%) are critical of the president’s handling of the military.

But these differences vanish when partisanship is factored into the analysis. Eight-in-ten post-9/11 veterans (83%) who identify with the Democratic Party approve of Obama’s performance as commander in chief—and so do 80% of all Democrats nationally. Similarly, three-quarters of all recent veterans (75%) who say they are Republicans disapprove of the job that the president is doing, compared with 70% of GOP partisans in the general population.

Veterans as a whole are roughly comparable to the general population in terms of religious affiliation, though there are some differences between those who served before and after 9/11.

For example, post-9/11 veterans are mostly younger and, like younger Americans overall, they are more likely than pre-9/11 veterans to say they have no religion in particular (30% vs. 15% for pre-9/11 veterans and 18% for all adults). Recent veterans also are less likely than older veterans to call themselves Protestants (45% vs. 55%) or Catholics (15% vs. 23%).

Reflecting similar age differences on church attendance among the general public, post-9/11 veterans don’t attend religious services as frequently as veterans from earlier eras; 28% of recent veterans do so at least weekly, compared with 38% of pre-9/11 veterans and 36% of the general public.

Life Satisfaction

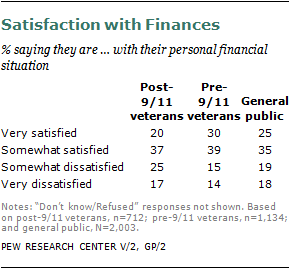

Regardless of when they served, most military veterans are at least pretty happy with their lives overall. They express high levels of satisfaction with their family life and give mixed marks to their financial situation. Post-9/11 veterans are more dissatisfied with their finances than are older veterans or the general public.

Among post-9/11 veterans, 29% say they’re very happy with how things are in their lives and 59% say they’re pretty happy. Just 12% say they’re not too happy—a slightly smaller share than among pre-9/11 veterans (17%) and the general public (20%). Post-9/11 veterans who served as commissioned officers are far more apt (58%) to be very happy with their lives than are noncommissioned officers (34%) and enlisted service members (21%).

Veterans and the general public alike overwhelmingly report satisfaction with their family life on the whole—63% of post-9/11 veterans, 69% of earlier veterans and 67% of all adults say they are very satisfied, and most of the rest report being somewhat satisfied on this measure. No more than one-in-ten report dissatisfaction.

Veterans and other adults reported less satisfaction on the whole with their personal financial situation than with their family life. Just 20% of post-9/11 veterans say they are very satisfied with their finances, a smaller share than pre-9/11 veterans (30%) and the general public (25%). Those who served since 9/11 report greater net dissatisfaction with their finances—42%, compared with 28% of pre-9/11 veterans and 37% of all adults.

Their dissatisfaction, in part, reflects the toll that the bad economy has taken on recent veterans. The unemployment rate for post-9/11 veterans at the end of the decade stood at 11.5%, about two percentage points higher than the jobless rate for all non-veterans (9.4%) at the same time.

Younger veterans have been particularly hard hit by the recession. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2010 21.9% of male veterans ages 18-24 from the post-9/11 era were unemployed. That is about the same as the jobless rate among male non-veterans in that age group (19.7%).6

A Road Map to the Report

The remainder of this report is organized as follows: Chapter 2 explores in more depth the attitudes of veterans on policy issues affecting the military in the post-9/11 era, including their views about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the tactics employed to fight them. Chapter 3 reports how veterans see their service; how they evaluate the rewards and burdens of military life; and what they experienced in combat. Chapter 4 tells the story of America’s veterans after they left the service, including the challenges they faced re-entering civilian life, the benefits they received from their military experience and the prevalence of service-related emotional problems, including post-traumatic stress. Chapter 5 reports the results of a national survey of the public that includes many of the same questions that were asked of veterans and explores in detail similarities and differences between the two groups. Chapter 6, the final chapter, presents a demographic profile of today’s military and examines the changes that have reshaped the armed forces since the draft was abolished in 1973. The appendices provide a detailed explanation of the survey methodologies and topline summaries of the survey research findings.