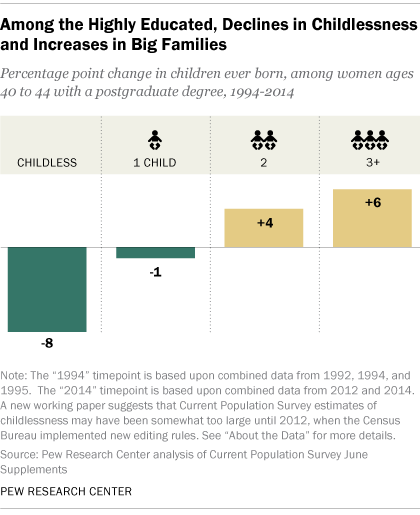

Among women in the United States, postgraduate education and motherhood are increasingly going hand-in-hand. The share of highly educated women who are remaining childless into their mid-40s has fallen significantly over the past two decades.1

This trend has likely been driven by demographic and societal changes. It coincides with women’s growing presence in managerial and leadership positions and suggests that an increasing share of professional women are confronting the inevitable push and pull of work-family balance. Previous Pew Research analysis has found that overall women devote fewer hours to paid work with each additional child they have. On average, a working-age woman with no children spends 27 hours per week in paid work, while a woman with three or more children spends 18 hours working. In addition, working mothers are more than three times as likely as working fathers to say that being a working parent has made it more difficult for them to advance in their career (51% vs. 16%).

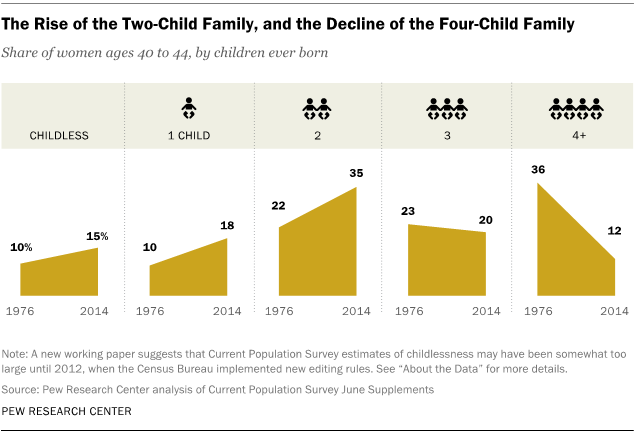

Fueled in part by the increases in motherhood among highly educated women, childlessness among all women ages 40 to 44 in the U.S. is at its lowest point in a decade.2 In 1994, 18% of all women at the end of their childbearing years had not borne a child. That number rose to 20% by the mid-2000s before declining to 15% in 2014. At the same time, the average number of children that U.S. women have in their lifetime has remained quite stable over the past 20 years, at about two children.

The fact that completed family size has changed little since the mid-1990s may seem counterintuitive, given the amount of attention often directed toward the so-called “Baby Bust” in the post-recession U.S. It is true that analyses based on changes in annual fertility rates have shown consistent declines in childbearing since 2007, suggesting that fertility is at an all-time low. However, these analyses are capturing fertility at one point in time, as opposed to the cumulative measure of lifetime fertility used in this analysis. Part of what accounts for the low fertility indicated by annual rates is the fact that many women are putting off having children until later in life, both due to broad cultural changes (such as increasing education), and due to the Great Recession, which intensified delayed childbearing, particularly among younger women. What remains to be seen is whether these declines in annual birth rates will continue, and will translate into lower lifetime fertility for women at the end of their childbearing years. Some experts suspect that, as with past economic downturns, women may ultimately “catch up” on their fertility, though one recent analysis suggests that fertility delayed due to the Great Recession may in fact be fertility foregone.

These findings are based on a Pew Research Center analysis of civilian women near the end of their childbearing years, using data from the 1976-2014 June Supplements of the Current Population Survey. The June Supplement is typically conducted every other year, and produces a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalized population of the U.S. While the overview and first section of this report analyzes childlessness and fertility among all women, the final section examines mothers only, focusing on trends and variations in the number of children that they have had in their lifetimes.

Other key findings:

- While fertility trends among highly educated women show a clear pattern of less childlessness and bigger families, the trends among less-educated women are not as clear-cut. Childlessness is down among women lacking a high school diploma and among women with a bachelor’s degree, but otherwise family size for these two groups has changed little since 1994. And among high school graduates, the share of women ages 40 to 44 with one child has increased, but there has been no change in the share with bigger families.

- The educational “gaps” in childlessness and in family size have narrowed in the past two decades, but they do persist. The more education a woman has, up to a bachelor’s degree, the less likely she is to become a mother. And among mothers, those with more education have fewer children than those with less education. For instance, just 13% of moms lacking a high school diploma have one child, while fully 26% have four or more, while among mothers with a master’s degree or more, 23% have only children and just 8% have four or more.

- Fertility patterns differ significantly by race and ethnicity. Some 17% of white women ages 40 to 44 are childless, compared with 15% of black women in the same age group, 13% of Asian women and just 10% of Hispanic women.

- Hispanic and black mothers ages 40 to 44 are especially likely to have large families. Fully 20% of Hispanic moms have four or more children, as do 18% of black moms. In comparison, just 11% of white mothers have four or more children, as do 10% of Asian mothers. Since 1988, there has been a dramatic decline in the share of mothers with four or more children among Hispanics, blacks and whites.

About the Data

Findings in this report are based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s June Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). The June Fertility Supplement was first administered in 1976 and is typically conducted every other year. Public-use data files prior to 1986 are not readily available, so analyses of pre-1986 timepoints are drawn from census tabulations.

Given the nature of the CPS data, a “mother” is here defined as any woman who has given birth to a child, while those who have not given birth are counted as “childless.” However, many women who do not bear their own children are indeed mothers. Estimates suggest that 7% of children living with a parent householder in the U.S. are living with either an adoptive parent or a stepparent.

This report defines the end of the childbearing years as ages 40 to 44, which has typically been the convention, partly due to the fact that few women have babies beyond these ages, and partly due to the fact that, until recently, data on the completed fertility of women ages 45 and older were not collected. While technology is extending the age at which women can have children, the vast majority still have children before age 45. In 2013, about 0.2% of births occurred to women ages 45 or older, and analyses from the Census Bureau show that childlessness among women ages 40 to 50 is similar to childlessness among women ages 40 to 44.

Analyses looking at all women, or at all mothers, are based upon data from single years. For the detailed analyses of educational, racial and ethnic differences in fertility, which are the central focus of this report, multiple years of data are combined in order to create sufficient sample sizes. The data from 2012 and 2014 are combined, and referred to as “2014”; data from 1992, 1994, and 1995 are combined, and referred to as “1994”; and data from 1986, 1988, and 1990 are combined and referred to as “1988”.

A new working paper suggests that prior to 2012, when new editing protocols were implemented by the Census Bureau, the Current Population Survey may have overestimated childlessness somewhat. This makes it difficult to determine the exact magnitude of changes in childlessness across time, though simulations suggest that childlessness is lower now than it was in 2004 and 2006, and no higher than it was around 1994, even taking the new editing protocol into account.

In 1992, the Census Bureau introduced a new variable with detailed categories of educational attainment allowing for definitive identification of individuals by whether they have a bachelor’s degree, a master’s degree, a Ph.D. or an M.D. Prior to that year, analyses of such detailed educational breaks was not possible. As such, the analysis of fertility by educational attainment begins with the 1992 data.

Data regarding racial and ethnic groups is available as early as 1986, but the sample sizes for Asian women ages 40 to 44 is so small that even combining multiple years does not produce an adequate sample size. As such, the fertility of Asian women could not be reliably estimated for the 1988 timepoint used in the report.

A Note on Terminology

References to respondents who are high school graduates or who have a high school diploma also include those who have earned an equivalent degree, such as a GED (General Educational Development) certificate.

References to respondents with “some college” include those who have a two-year degree.

References to respondents with “postgraduate” degrees include all people who have at least a master’s degree.

All references to whites, blacks and Asians are to the non-Hispanic components of those populations. Asians also include Pacific Islanders. Hispanics are of any race.