People think that jobs in this country are being reshaped. They see many forces at play: the nature of employment itself is changing; benefits and compensation are being restructured; competition is coming from multiple directions, including outsourcing, imports, and the infusion of technology in workplaces; demands are growing for higher levels of performance and retooled worker competencies, including soft skills like social intelligence; and there is no clear consensus on which entities should be responsible for helping workers meet these challenges. Americans see increased emphasis on workers to continually improve their skills to keep up with job-related developments. Fully 71% believe demands to improve work skills will increase in the years to come.

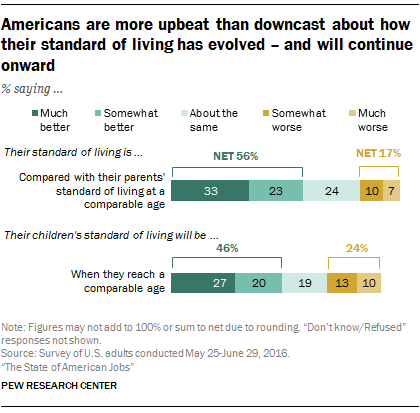

At the same time, things do not feel relentlessly pressured. People also see a generational march that feels more positive than negative. More than half (56%) believe their standard of living is better than their parents’ standard of living when their parents were their age. And more think their children’s standard of living will be better than their own (46% believe this) than think things will get worse for their kids (24% think that).

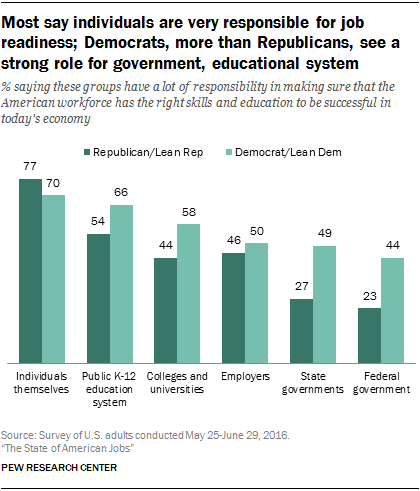

As they assess jobs in the knowledge economy, large majorities say workers need a mix of technical skills (understanding computers is a must), comfort with diversity, and writing and communications training to succeed. Fully 72% of Americans subscribe to the bootstrap notion that individuals themselves have “a lot” of responsibility in getting the skills and education necessary to succeed in the modern workforce. Still, partisan political differences emerge as people try to apportion responsibility for who else or what else should assume the burden of worker preparation. Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say public schools, colleges, and the federal and state governments have a lot of responsibility for making sure U.S. workers are prepared for today’s jobs.

This chapter examines people’s answers about what they consider to be the present state of jobs in America, how the nature of work is changing, what skills people think are necessary for modern workplaces, and where responsibility lies when it comes to providing workers with the skills and education they need to succeed.

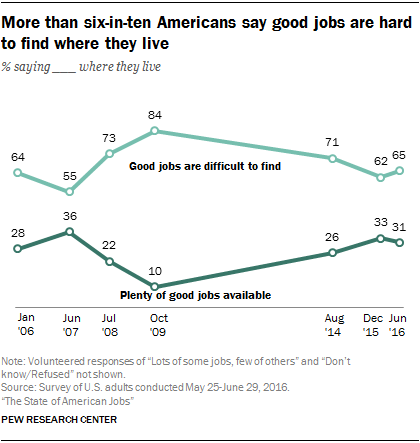

A majority of Americans do not think good jobs are available in their communities, but views of the situation have improved since the height of the Great Recession

By a two-to-one ratio, people think good jobs are difficult to find where they live. Some 65% of adults say this, compared with 31% who believe there are plenty of good jobs where they live. When the issue is simply the availability of jobs – whether good jobs or not – views remain negative, on balance: 56% of Americans assert that jobs are hard to find in their communities, while 37% say plenty of jobs are available.

A broad pattern of pessimism pervades people’s views when they think about the prospects of good jobs in their areas. Even those with full-time jobs, those who live in high-income households and have high levels of education, those in every job sector, those in small companies and those in larger corporations, hourly workers and salaried workers, and those in every region of the country and every type of community are more downcast than upbeat about the availability of good jobs. Still, things were considerably worse in a 2009 survey by Pew Research, when 84% of Americans reported good jobs were hard to find and only 10% said plenty of good jobs were available.

While at least half of adults across all of these groups think good jobs are hard to find where they live, some groups are particularly pessimistic. For example, 72% of those with annual family incomes of less than $30,000 say good jobs are hard to find, compared with 56% of those with incomes of $75,000 or more. And about three-quarters (76%) of adults living in rural communities say good jobs are hard to come by where they live, compared with 62% of those living in urban or suburban communities. Younger adults ages 18 to 29 are more bullish about jobs than their older counterparts – 40% say plenty of good jobs are available locally, compared with 30% or less among older age groups.

Most think they have it as good as or better than their parents had it, and most think their children will reach or exceed their own standard of living

Over the years, Americans’ views about their standard of living have held relatively steady and have registered relatively optimistic when they compare their lives to their parents’ lives and when they ponder the circumstances they believe their children’s generation will face.

In this survey, 56% of adults say their standard of living is “much better” (33%) or “somewhat better” (23%) than their parents enjoyed at the same age. Some 24% report their standard of living is about the same as their parents. And 17% describe it as “somewhat worse” (10%) or “much worse” (7%) than their parents at a similar age. These are not very different readings from previous survey findings during strong economic times in the mid-2000s and during tougher circumstances when the effects of the Great Recession were still being felt in 2010.

Looking ahead, people are a bit less sanguine about their children’s prospects, but they are more upbeat than despairing. Some 46% believe their children will enjoy a “much better” (27%) or “somewhat better” (20%) standard of living when they are their parents’ age. Roughly a fifth (19%) believe their kids will enjoy about the same standard of living, while only 13% believe it will be “somewhat worse” and 10% believe it will be “much worse” for their children when they are the same age their parents are today. Again, these views have not varied to any great degree in Pew Research Center surveys since the Great Recession began in 2007.

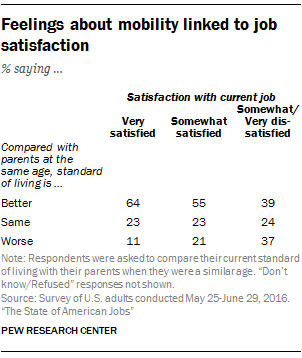

To some extent, people’s current job satisfaction is tied to their views about how things have changed from their parents’ circumstances to now. Among employed adults who are very satisfied with their job, 64% say their standard of living is better than their parents’ was; among those who are somewhat satisfied, 55% say things are better for them than they were for their parents; among those who are somewhat or very dissatisfied, 39% say they are better off than their parents were.

Yet, people’s satisfaction with their jobs does not necessarily translate into hopes for their children’s standard of living. As people think about where their children will be, those who are very satisfied with their current job are no more likely to be hopeful for their kids’ lives than those who are very dissatisfied with their jobs.

In the past generation, people think work life has become less rewarding and more demanding

Despite their relatively upbeat assessments about their standard of living and prospects for the future, many Americans think jobs in the U.S. are less secure, more pressured, less rewarding in terms of benefits, and less built on worker loyalty to employers than in the past.

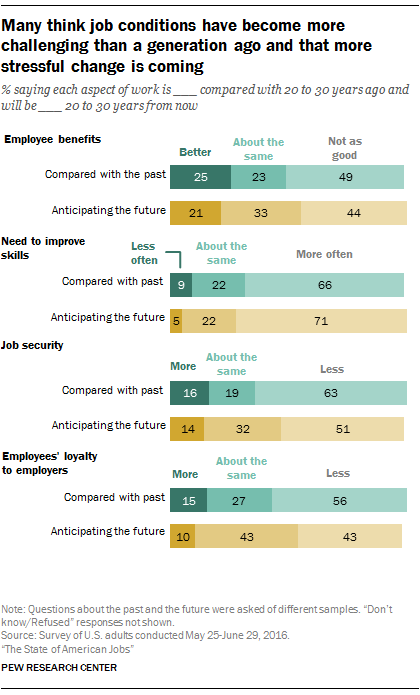

Two-thirds of all adults (66%) believe today’s workers have to improve their work skills more often than workers of the previous generation did in order to keep up with developments tied to jobs. Some 63% say there is less job security for workers now than there was 20 to 30 years ago. About half (49%) think employee benefits such as health insurance, paid vacation and retirement plans are not as good as before. This compares with 25% who say benefits are better now and 23% who say they are about the same.

When it comes to employee loyalty to employers, 56% of adults believe today’s workers show less loyalty to their employer, while 15% say there is more loyalty from workers now and 27% rank the loyalty level about the same as a generation ago.

A 2006 Pew Research Center survey found a similar level of angst about workplace trends and conditions. About six-in-ten (64%) said the average working person had less job security in 2006 than 20 to 30 years earlier, and 70% said workers were required to update their skills more often than in the past to keep up with changes in the workplace. Roughly half (51%) said workers showed less loyalty to their employer than they had in the past.

As they look at the future, large numbers of Americans think things will intensify in the coming 20 to 30 years. Roughly seven-in-ten (71%) believe that workers will have to improve their skills more often in the future in order to keep up with job-related developments. About half (51%) think there will be less job security in 20 to 30 years, while only 14% predict more job security for workers, and 32% say this will stay about the same.

A plurality (44%) believe employee benefits will not be as good in the future, while 33% think benefits will be about the same and 21% believe they will be better.

When it comes to worker loyalty, 43% say employees will show less loyalty to their employers in the future, while an identical share believe the current levels of loyalty will prevail. Only 10% believe that workers will have more loyalty to their firms 20 to 30 years from now.

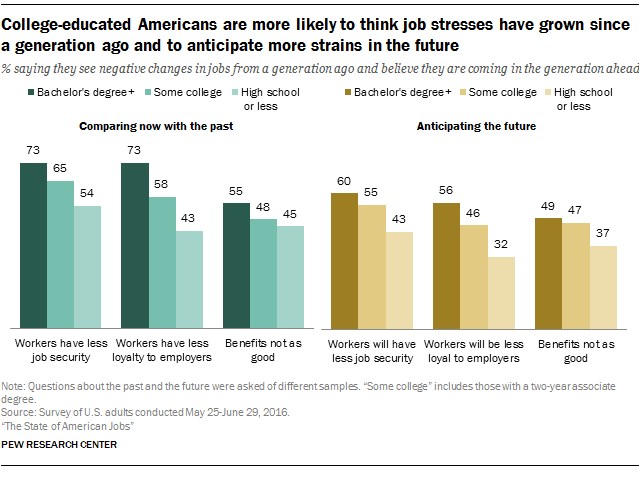

There are clear socioeconomic class differences as people look at the changing nature of jobs

There are clear patterns by income and education in views about the present and future of work. Those in households with higher income and people with higher levels of education tend to be more discouraged about workplace trends than those with lower incomes and lower levels of education. For example, 73% of those with college degrees or more believe that there is less job security now for workers than there was 20 to 30 years ago, compared with 65% of those with some college education and 54% of those with a high school diploma or less. Moreover, 75% of those in households earning $75,000 or more say job security has worsened in the past generation, while 63% of those in households earning $30,000 to $74,999 and 53% of those in households earning under $30,000 agree.

Interestingly, those who have management jobs and those who are members of unions are equally likely to believe that job security has worsened in the past generation: 73% of adults in those job categories say job security has worsened. The same dynamic holds when it comes to employee benefits: 63% of both managers and union members say employee benefits are not as good now as 20 to 30 years ago. Some 57% of union members and 68% of managers believe employee loyalty to employers has lessened in the past generation.

On the issue of how things will look in the next 20 to 30 years, the other noteworthy pattern relates to age. Americans ages 50 and older are more likely than those who are younger to think that worker benefits will not be as good for those working 20 to 30 years from now (50% vs. 39%) and that there will be less job security in the future (54% vs. 49%).

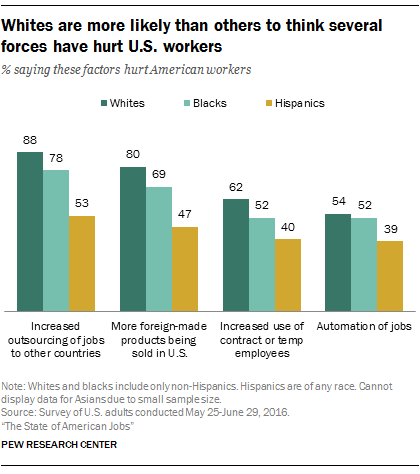

People think the greatest harms to U.S. workers are outsourcing and imports, but they are less worried about immigrants’ impact on jobs than they were a decade ago

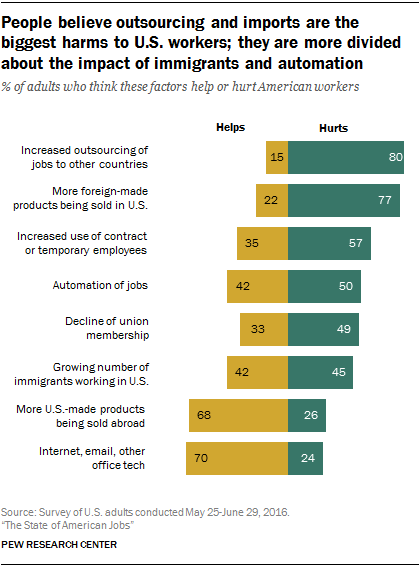

The survey measured public reactions to several key economic and workplace trends. The public ranks outsourcing of jobs and a rise in imports as the biggest threats to American workers. Fully 80% think outsourcing has done more to hurt than help workers, and 77% believe imports have taken their toll. At the other end of the spectrum, 70% of Americans say the internet, email and other office technology have helped workers and 68% think exports have helped.

The increased use of contract or temporary employees is viewed as a net-negative by the public: 57% say this trend hurts American workers, while 35% say it helps. Half of adults say automation has hurt U.S. workers vs. 42% who see it as a helpful trend, and 49% say the decline in union membership has hurt workers, while 33% say it has helped.

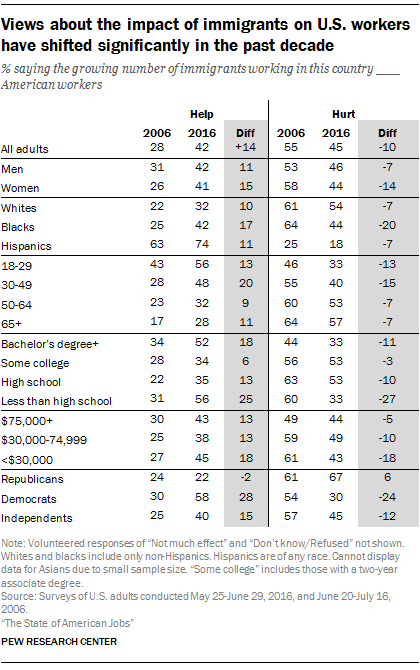

There is a divided verdict when it comes to Americans’ assessment of the impact of immigrants: 45% of adults now believe that the growing number of immigrants working in the U.S. hurts workers and 42% say having more immigrants helps workers. This is a noteworthy change from Pew Research Center findings from 2006, when there was a nearly two-to-one view in the public that the growing number of immigrants hurt U.S. workers. Some 55% of Americans said a decade ago that immigration hurt workers, compared with 28% who thought immigration helped workers.

Some of the biggest increases in positive views about the impact of immigrants have come among Democrats, blacks, and those with less than a high school diploma. These groups are all notably more likely now than in 2006 to think the growing number of immigrants helps workers.

There are major political divisions over whether more immigrants help or hurt U.S. workers

In the current survey, there are sharp political divides on the impact of immigrants on the job situation. Two-thirds (67%) of Republicans say the growing number of immigrants working in this country hurts American workers, while only 30% of Democrats agree with this assessment. Roughly six-in-ten (58%) Democrats say this trend helps workers. Independents are split: 45% say immigrants hurt, while 40% say they help. The views of Democrats have substantially shifted and softened towards immigrants in the past decade. In 2006, fully 54% of Democrats said that the growing number of immigrants was hurting workers, while only 30% said it helped workers. Over this same period, Republicans’ views have hardened somewhat, as a larger share now say having more immigrants in the U.S. hurts workers (67% today, up from 61% in 2006).

There are also differences tied to race and ethnicity. In 2016, whites are more likely than Hispanics and blacks to think that growing numbers of immigrants hurt workers: 54% of whites say that, compared with 44% of blacks and 18% of Hispanics. A decade ago, 64% of blacks felt that more immigrants hurt U.S. workers. Thus, in the past 10 years there has been a 20-point drop among blacks in their view that immigrants hurt American workers. At the same time, there has been a 17-point increase in the share of blacks who believe that greater numbers of immigrants help workers.

In addition, age is tied to people’s views about how the automation of jobs, the growing number of immigrants, the increased use of contract workers and the increase of imports are affecting American workers. Younger adults ages 18 to 29 are more likely than their elders to think these economic forces help American workers.

With the exception of the automation of jobs, whites are generally more likely than blacks or Hispanics to see harm in those instances. In addition, 88% of whites believe that increased outsourcing hurts American workers, compared with 78% of blacks and 53% of Hispanics.

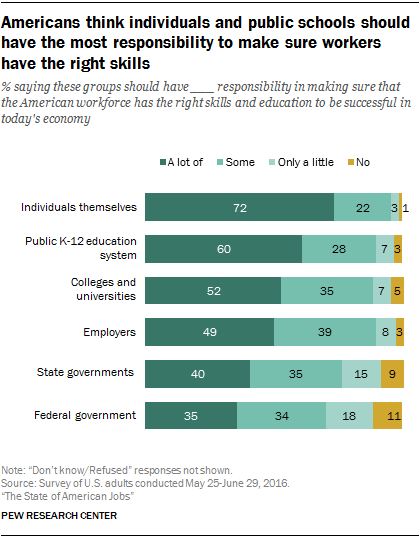

People think workers themselves and public schools have the most responsibility to make sure the U.S. workforce has the right skills and schooling to be successful

Majorities of Americans assert that the main responsibility for preparing and keeping workers up to speed on their job requirements falls on individual workers themselves and the elementary and secondary public school systems. Roughly seven-in-ten (72%) believe that individuals have “a lot” of responsibility to make sure workers have the right skills and education to be successful. These views are strongly consistent throughout different groups. Majorities of every major demographic cohort believe that individuals have a lot of responsibility for their job preparedness.

Additionally, 60% say that public K-12 schools bear a lot of responsibility in preparing and training the workforce. For some groups this ranks nearly as high a factor in job preparedness as the role of individuals themselves. This is especially true among racial and ethnic minorities, those in poorer households, those with lower levels of education, and those who are Democrats.

After that, the public assigns responsibility this way: 52% believe colleges and universities have a lot of responsibility, 49% think employers have a lot of responsibility, 40% say state governments have a lot of responsibility, and 35% say the federal government has a lot of responsibility. It is useful to note that in the broadest terms there is the least support among people for the federal government holding a great deal of responsibility for preparing American workers to be successful.

Beyond those broader patterns lie some other noteworthy demographic differences in people’s assignment of responsibility for worker preparedness and skills acquisition.

A more detailed breakdown looks like this:

Individuals themselves: : As noted, 72% of Americans say that people have a lot of responsibility to make sure they have the right skills and education to be successful in today’s economy. Among those who are more likely than their demographic counterparts to believe that are those living in households earning more than$75,000 (79%), those with a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education (79%) or some college (75%), Republicans and independents who lean to the Republican Party (77%) and whites (74%).

The K-12 education system: Some 60% of all adults say that public elementary and secondary schools have a lot of responsibility in making sure workers are educated and have the right skills for today’s economy. Among those more likely to support this idea than their counterparts: Democrats and Democratic leaners (66%), Hispanics (66%) and blacks (65%).

Colleges and universities: About half of Americans (52%) say that colleges have a lot of responsibility to make sure that U.S. workers have the rights skills and education to be successful in today’s economy. Among the groups that are more likely than their counterparts to back that: Hispanics (63%), those who did not complete high school (62%) and Democrats and Democratic leaners (58%).

Employers: About half (49%) subscribe to the idea that employers have a lot of responsibility to make sure workers have the right skills and education to be successful in today’s economy. Among those more likely than their counterparts to say this: Hispanics (61%) and blacks (54%), those with a high school diploma or less (55%), and those in households earning less than $30,000 (55%).

The federal government: About a third (35%) of adults say that the federal government has a lot of responsibility in making sure the American workforce has the right skills and education to be successful. Those more likely than their counterparts to believe this include Hispanics (56%), blacks (52%), those in households earning less than $30,000 (49%), Democrats and independents who lean Democratic (44%) and those with high school diploma or less (43%).

The same pattern of responses largely applies to those who say that state governments have a lot of responsibility in making sure that the American workforce has the right skills and education to be successful in today’s economy. Overall, 40% of Americans believe that.

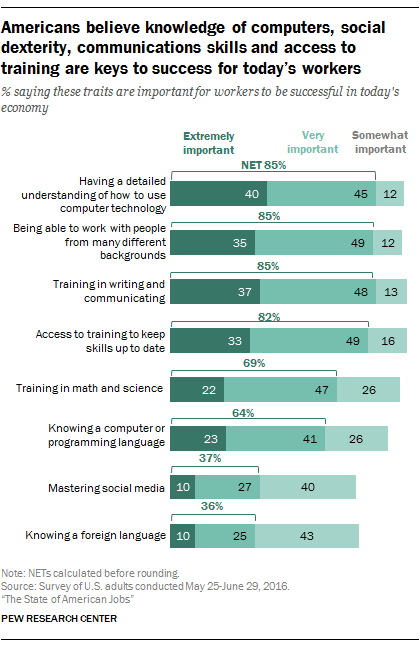

Americans think workers need a mix of technical, social and communications skills to succeed today

When people think about what it takes for workers to be successful these days, they rank several traits as highly important: knowledge of computers (85% say this is “extremely” or “very” important), ability to work with those from diverse backgrounds (85%), training in writing and communication (85%) and access to training to update skills (82%).

Next on the list comes training in math and science – 69% believe that is extremely or very important – and knowing computer programming (64%). A smaller share of Americans also believe that mastering social media (37%) and knowing a foreign language (36%) are at least very important for success in the modern workplace.

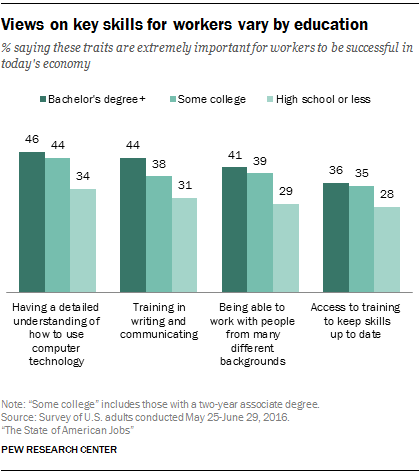

The traits most frequently cited as important by Americans are anchors of the skill set of workers in the knowledge economy. It is not surprising, then, that some of the starkest differences in people’s answers are linked to their level of education. Those with higher educational attainment are more likely than others to think that knowledge of computers, writing and communications training, facility in working with people from many different backgrounds and access to more training on skills are extremely important for workers to be successful now. For instance, 46% of those with college degrees or higher and 44% of those with some college consider knowledge of computers to be extremely important, compared with 34% of those with a high school diploma or less.

Those who work in the manufacturing and farm sectors and those who work in the hospitality industry are less likely than those who work in the education, trade or health care sectors to believe that mastering computer technology and having training in writing and communications are extremely important traits to bring to the job.23 Moreover, those who do manual labor are less likely than others to think that computer mastery and communications skills are essential for workers. Manual laborers are also less likely than others to believe workers should be able to work with people from many different backgrounds.

Women are more likely than men to cite some traits as extremely important for being a successful job holder in today’s economy. Some 46% of women believe that having detailed understanding of computers is extremely important for successful workers compared with 34% of men who believe that. There is a similar-sized gender gap when it comes to training in writing and communication: 42% of women, vs. 32% of men, say this is an extremely important trait for today’s workers to have.

Additionally, there are some differences in people’s views tied to race and ethnicity. Hispanics are less likely than blacks or whites to think that it is extremely important for worker success to know computer technology, be trained in writing and communications, and be able to work with others from diverse background. At the same time Hispanics are more likely than whites to think that knowing a foreign language and mastering social media are extremely important.