Blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and math jobs, relative to their presence in the overall U.S. workforce, particularly among workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

There is widespread support among Americans – including those in STEM and non-STEM jobs – for the ideals of racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace. Among STEM workers, blacks stand out for their concerns that there is too little attention paid to increasing racial and ethnic diversity at work, their high rates of experience with workplace discrimination and their beliefs that blacks are not usually met with fair treatment in hiring decisions or in opportunities for promotion and advancement where they work.

In this regard, blacks working in STEM jobs share common ground with Asians and, to a lesser degree, Hispanics who are all much less likely than whites in such jobs to believe that members of their own racial or ethnic group are usually treated fairly, particularly when it comes to opportunities for promotion and advancement.

Most blacks in STEM positions consider major underlying reasons for the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics in science, technology, engineering and math occupations to be limited access to quality education, discrimination in recruitment and promotions and a lack of encouragement to pursue these jobs from an early age.

A majority of Americans view racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace as important

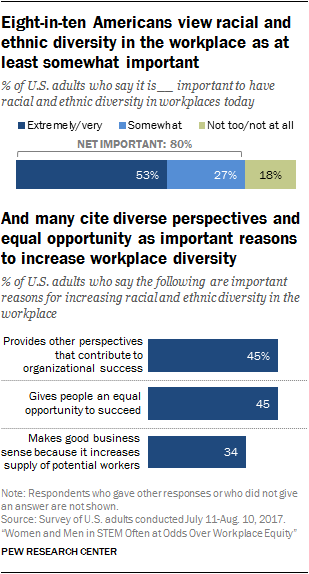

The American public not only places some level of importance on gender diversity in the workplace, but these views extend to racial and ethnic diversity, as well. Eight-in-ten Americans say it is at least somewhat important to have racial and ethnic diversity in today’s workplaces, including around half who categorize this as “extremely” (26%) or “very” important (27%).

By contrast, relatively few Americans view racial and ethnic diversity in today’s workplaces as “not too” (9%) or “not at all” (9%) important.

When asked which, if any, are important reasons for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace, 45% of U.S. adults say it provides other perspectives that contribute to the overall success of companies and organizations, while the same share say it gives people an equal opportunity to succeed. A smaller share (34%) say an important reason for creating more racially and ethnically diverse work environments is that it makes good business sense because it increases the supply of potential workers.

Broad public support for racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace is in keeping with prior surveys on values related to diversity, more generally. For example, a 2017 Pew Research Center report found that a majority of Americans believe an increasing number of people from different races, ethnic groups and nationalities in the U.S. make the country a better place to live.

Blacks employed in STEM place a high level of importance on workplace diversity

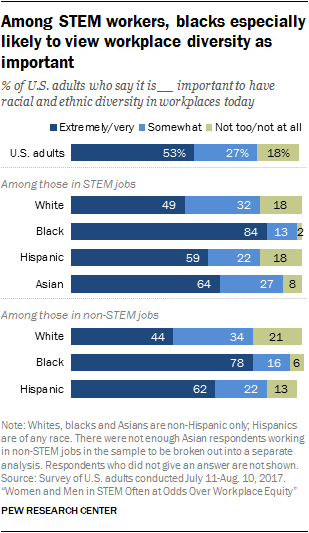

Majorities of white, black, Hispanic and Asian STEM employees view racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace as at least somewhat important, but there are wide racial and ethnic differences in the degree to which they consider it important.

Blacks employed in STEM are far more likely than their white counterparts to say racial and ethnic diversity in the workplace is extremely or very important (84% vs. 49%, a difference of 35 percentage points). Sentiments on this issue among Hispanic and Asian STEM employees tend to fall in between these groups.

On this measure, STEM workers look similar to those in other kinds of jobs. Blacks and Hispanics in non-STEM jobs, similarly, are more likely than are whites in such jobs to believe that racial and ethnic diversity at work is at least very important.

Blacks in STEM are about four times as likely as whites in STEM to say their workplace doesn’t pay enough attention to increasing racial and ethnic diversity

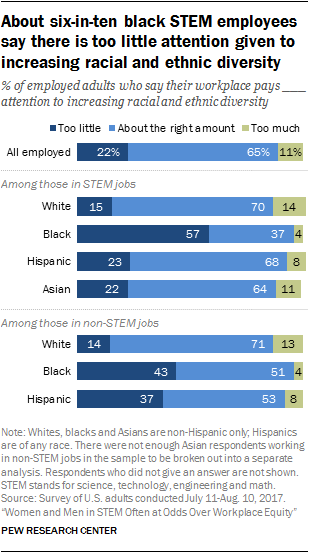

When asked if they think their workplace pays too little, too much or just about the right amount of attention to increasing racial and ethnic diversity, about two-thirds (65%) of employed adults say their workplace is paying the right amount of attention, 22% believe there is too little focus, while 11% say too much attention is given to this issue.

Black and white STEM employees rate their employers’ commitment to this issue very differently. Roughly six-in-ten blacks (57%) working in a STEM job say their workplace pays too little attention to increasing racial and ethnic diversity. By comparison, just 15% of whites in this field say this.

Majorities of whites, Hispanics and Asians working in STEM think their workplace pays about the right amount of attention to increasing racial and ethnic diversity.

Whites working in STEM jobs hold similar views on this issue to whites in non-STEM jobs. But black STEM employees are more likely than blacks in non-STEM jobs to say their employer pays too little attention to increasing diversity (57% vs. 43%). The reverse is true for Hispanics: Those in STEM jobs are less likely than those who do not work in STEM to say their workplace is not paying enough attention to these issues (23% vs. 37%).

About half of STEM workers believe limited access to quality education is a major reason why blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in STEM jobs

Blacks and Hispanics made up around a quarter (27%) of the overall U.S. workforce as of 2016, but together they accounted for only 16% of those employed in a STEM occupation. Past studies have raised a number of possible reasons for this underrepresentation, including the need for racially and ethnically diverse mentors to attract more blacks and Hispanics to these jobs, limited access to advanced science courses, or socioeconomic factors that may disproportionally affect these communities.36

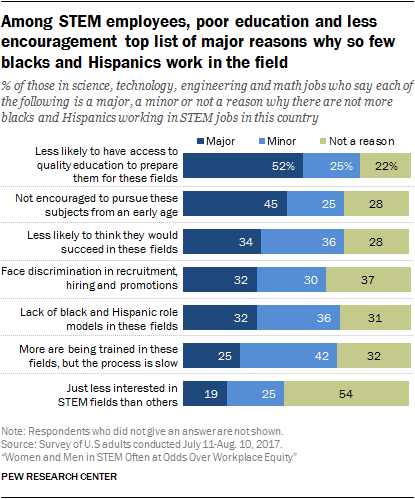

When asked about the underlying reasons why blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in this type of work, those working in STEM point to factors rooted in educational opportunities. Some 52% of those with a STEM job say a major reason for this underrepresentation is because blacks and Hispanics are less likely to have access to quality education that prepares them for these fields, while 45% attribute these disparities to these groups not being encouraged at an early age to pursue STEM-related subjects.

At the same time, around a third of people working in STEM attribute the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics to these groups not believing in their ability to succeed in these fields (34%), the lack of black and Hispanic role models in these fields (32%), and racial/ethnic discrimination in recruitment, hiring and promotions (32%).

A slight majority of STEM employees dismiss the idea that blacks and Hispanics are uninterested in these subjects: 54% say blacks and Hispanics being less interested in STEM is not at all a reason for the racial/ethnic employment gaps present in the field.

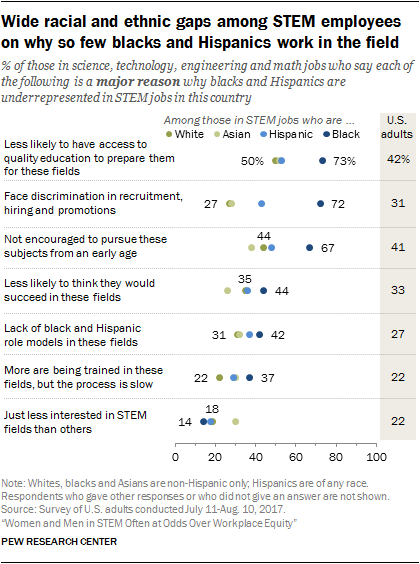

There is wide disagreement across racial and ethnic groups on how much discrimination contributes to these racial/ethnic disparities. Among those in STEM, 72% of blacks say a major reason why blacks and Hispanics are underrepresented in these jobs is because they face discrimination in recruiting, hiring and promotions; by contrast only around a quarter of whites (27%) and Asians (28%) say this. Hispanic STEM employees fall in between these groups, with 43% citing this as a major reason for these disparities.

Blacks in STEM are far more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to attribute this underrepresentation to lack of access to a quality education or lack of encouragement at an early age to pursue these subjects. Racial gaps on other items are far more modest.

People who are employed in a STEM job are more likely than those working in non-STEM jobs to cite lack of access to quality education (52% vs. 42%), lack of encouragement to pursue subjects at an early age (45% vs. 40%), and lack of black and Hispanic role models working in the field (32% vs. 27%) as major reasons why these groups are underrepresented in STEM jobs.

By about 20 percentage points, blacks in STEM are more likely than blacks in non-STEM jobs to think the lack of quality schooling and lack of encouragement to study these subjects are major reasons that blacks and Hispanics are not widely represented in STEM jobs. Blacks in STEM jobs are also more likely than those in non-STEM occupations to think discrimination is a major reason behind the underrepresentation of blacks and Hispanics (72% vs. 58%). Views among Hispanics on this tend to be similar across those working in STEM and non-STEM jobs.

Blacks in STEM jobs are particularly likely to say they have experienced workplace discrimination because of their race

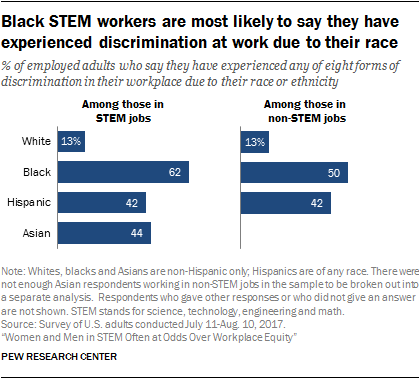

Overall, one-quarter of workers say that they have ever experienced any of eight forms of discrimination in the workplace due to their race or ethnicity.

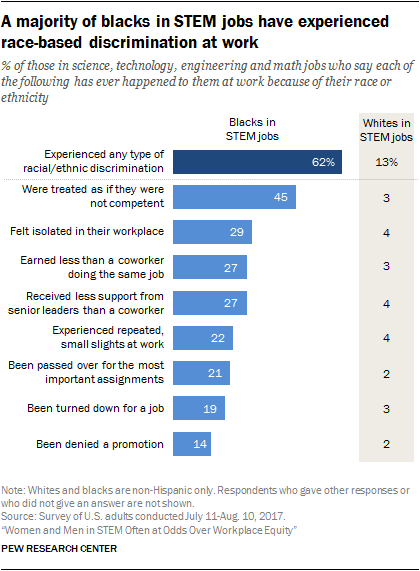

Black STEM employees are especially likely to say they have experienced discrimination at work – in a current or previous job; 62% of blacks in STEM say this compared with 44% of Asians and 42% of Hispanics in STEM jobs.

Blacks in STEM jobs tend to report experiencing workplace discrimination due to race more than do blacks in non-STEM jobs (62% vs. 50%).37 Hispanics in STEM and non-STEM jobs are equally likely to say they have experienced workplace discrimination because of their race or ethnicity (42% each).

Among those experiences, some 45% of black STEM workers say that they have had someone treat them as not competent because of their race (this compares with 28% of black workers in other occupations who say the same) and 29% have felt isolated in their workplace because of their race (compared with 16% of black non-STEM workers). See Appendix for more details.

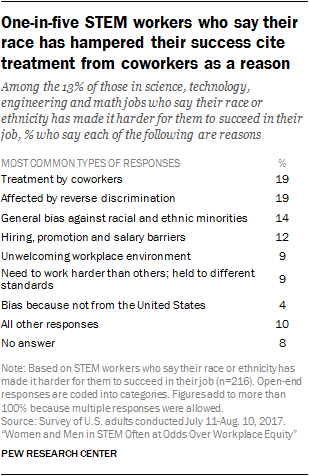

One-in-five STEM workers who say their race has hampered their success point to treatment from coworkers as the reason

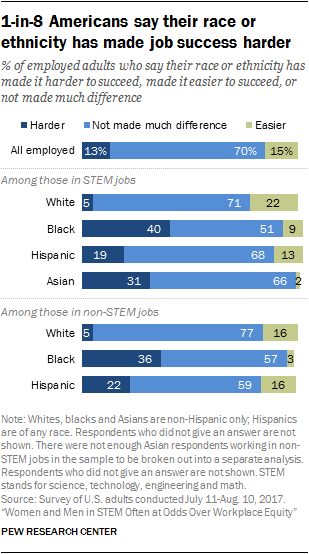

The vast majority of white STEM workers say that their race or ethnicity has either made no difference to success (71%) or has made it easier to succeed in their job (22%), while 5% of white STEM workers say that their race or ethnicity has made success in their job harder.

Blacks and Asians in STEM jobs, followed by Hispanics, are more likely than white STEM workers to say that their race or ethnicity has made it harder to find success in their job.

In this, black and Hispanic STEM workers tend to hold similar views with blacks and Hispanics working in other kinds of occupations.

STEM workers who say that their race or ethnicity has made it harder to succeed in their job were asked to elaborate on this judgment. Roughly one-in-five in this group (19%) say their race has made job success harder because of the resulting treatment from coworkers. Respondents gave examples of how their race leads to coworkers making assumptions about their competency or automatically associating them with negative stereotypes.

“I’m automatically thought of as I’m not going to be a hard worker because of the color of my skin.” – Black woman, nurse, 32

“People have preconceived ideas of what I am capable of doing.” – Black man, physical scientist, 39

“Hispanics are looked down upon as stupid.” – Hispanic woman, physician, 48

“People look at the color of my skin and automatically start doubting my ability and my knowledge of my job.” – Asian woman, surgeon, 45

Another 14% cite a general bias against racial and ethnic minorities in the workplace and the world:

“My skills are secondary to my race. My race is seen first.” – Black woman, database administrator, 60

“The workplace is still geared to the promotion of whites over minorities regardless of the laws in place to promote equality in the work force.” – Hispanic man, engineer, 65

About one-in-eight (12%) of this group say they have faced specific barriers in hiring, promotions and salary in the form of lower pay or fewer opportunities for promotion than their white coworkers.

“As a black woman I get looked over for promotions or advancement because of stereotypes. It is believed that black people as a whole are lazy and unqualified which is totally the opposite. Sometimes I feel that people are threatened by me because they know I am capable, qualified and competent to do the job.” – Black woman, nurse, 34

“Opportunities are usually offered to my white counterparts before they are offered to me.” – Hispanic man, physical scientist, 60

Roughly one-in-ten (9%) of this group describe the feeling of being unwelcome in their workplace.

[my]

“This ‘other-ness’ exists intentionally or unintentionally between those of a minority and those of a majority from lacking of common cultural background. Relationships at work appear polite on surface but reluctant tendency in willing to share limited opportunities the same way, which I felt in a previous job where whites and males were overwhelmingly a majority.” – Asian woman, engineer, 56

A similar share of this group (9%) say they are held to different standards than their coworkers, leading them to need to work harder than others to achieve the same results.

“As an African American woman, I found that I have always had to work harder than others in the workplace. I am one of the few women that has been in the computer field for 30 years, which has always been mostly men.” – Black woman, computer worker, 60

“Feel like I have to constantly prove myself and jump through loopholes.” – Asian woman, nurse, 38

About two-in-ten STEM workers (19%) who responded to this open-ended question said that their race has made success in their job harder because they feel that they face reverse discrimination.

“As a white male nothing is a given now, you have to fight harder to overcome institutional and government reverse discrimination.” – White man, industrial and medical engineer, 55

“White males are an undesirable classification currently in environments seeking the managed utopia of balance and ‘diversity.’” – White man, computer worker, 52

“Reverse discrimination is still present in the workforce today. People with the same skills and experience, but different ethnicities, have different opportunities. A person formally classed as a minority will get preference over a white Caucasian.” – White man, engineer, 58

[a]

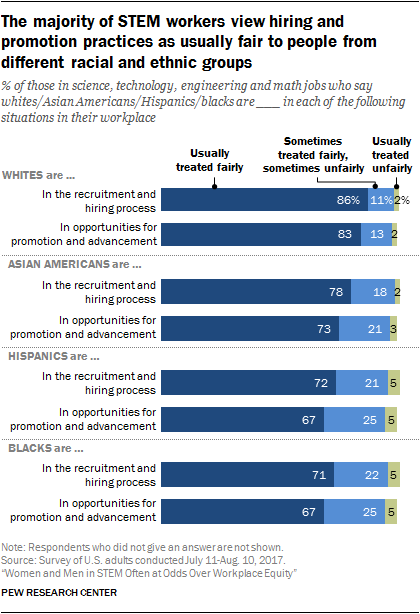

Most STEM workers see fair treatment in hiring and promotion processes across race and ethnic groups, but there are wide disparities between whites in STEM jobs and others

Overall, the majority of the public believes that different racial and ethnic groups are usually treated fairly in their own workplace in the recruitment and hiring process and in opportunities for promotion and advancement. On average, a larger share of STEM workers believe this is the case than do non-STEM workers.

Among STEM workers, more say that whites are usually treated fairly in both the hiring and promotion processes in their own workplace than say the same for Asian Americans, Hispanics and blacks in each of these situations.

There are sizable differences in perspective about this issue across racial and ethnic groups, however. About four-in-ten blacks in STEM jobs believe that blacks are generally treated fairly in recruitment (43%) or in advancement opportunities (37%). By contrast most white STEM workers believe that blacks are usually treated fairly in these processes (78% say this about hiring, 75% about advancement opportunities).

Similarly, there are wide differences in perceptions of fair treatment between Asians and whites working in STEM jobs, particularly in terms of advancement opportunities. About half of Asians in STEM jobs (53%) say that Asian Americans are usually treated fairly in opportunities for promotion and advancement. In contrast, 79% of white STEM workers believe this usually occurs.

Some 59% of Hispanics working in STEM jobs say that Hispanics are usually treated fairly when it comes to promotion and advancement opportunities; in contrast, most whites in STEM jobs (74%) believe Hispanics are usually treated fairly when it comes to promotions. On hiring processes, Hispanics and whites working in STEM jobs tend to agree that Hispanics are usually treated fairly (72% of Hispanics and 78% of whites in STEM jobs say this). For details, see Appendix.

In their own words: Advice from women and minority groups about how to attract more people like themselves to jobs in STEM

“It needs to be emphasized as early as in elementary school so that the opportunities are considered as much of a viable career path as other vocations such as social work, teaching and nursing. Black women need to be invited into the classroom to speak to students so that the students know that there are others out there that are blazing the trails for them and that can encourage them in their academic and career pursuits.” Black woman, engineer, 57

“You must introduce those fields early in the elementary school years. Then continue to build on that by establishing STEM clubs and activities. Provide information to parents about local/community STEM events for continued interests. Most of all, make sure that any STEM student has the rigorous preparation that will be needed to get them accepted into college and able to handle the nature of the college level classes.” Black woman, nurse, 49

“Providing opportunities such as putting upgraded computers and/or science labs in inner-city schools, libraries and community centers. Black men currently in the STEM industries must be visible to the younger generation in order to show the value of those skills and the career implications.” Black man, systems engineer, 30

“By encouraging these fields in early education and making available mentors, tutoring and opportunities to experience various fields early on in education. Also when people, especially children, see themselves reflected in the world around them they tend to pursue various opportunities in education and employment as they become adults. Having a government that believes in science and technology and budgets monies (sic) to encourage growth and development in these fields.” Hispanic woman, nurse, 68

“This can be done by highlighting successful examples in these fields. Schools can introduce students with Asian background to former successful students from the same ethnicity. In this way, they have the role models and will be encouraged to believe in themselves.” Asian woman, biological researcher, 24

“Need to better promote jobs – more emphasis on diverse opportunities, higher pay and flexible work-life balance.” Asian woman, physical scientist, 26

“Have hands on learning that is educational, fun and teaches students to learn through doing/building the work so they can see an end result instead. Not just numbers and theory on paper and lecture.” Hispanic man, respiratory therapist, 58

“K-8 teaching needs to be designed to make these subjects more interesting and accessible to girls. Teachers need to be explicit about the need for more women in STEM jobs, and help girls feel that they have a reason to pursue these fields in spite of the somewhat intimidating gender breakdown of higher level classes.” White woman, K-12 math teacher, 42

[Grace]