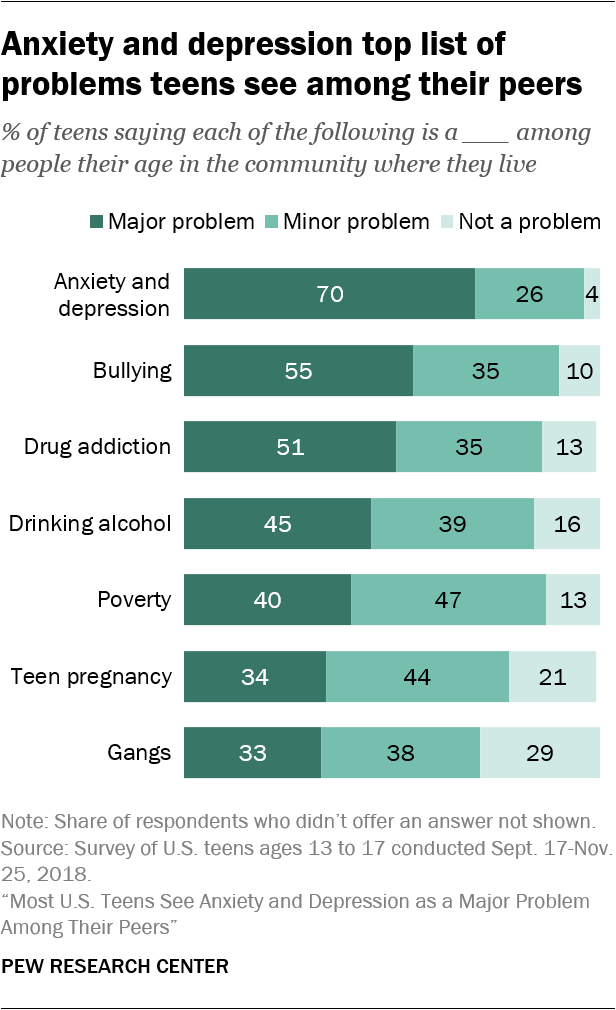

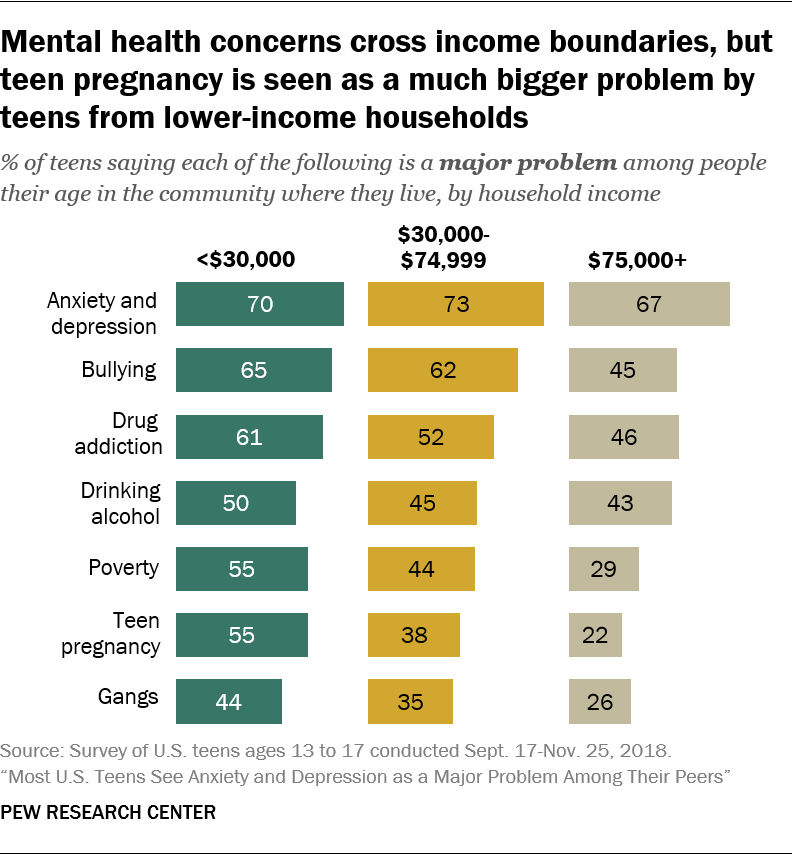

Anxiety and depression are on the rise among America’s youth and, whether they personally suffer from these conditions or not, seven-in-ten teens today see them as major problems among their peers. Concern about mental health cuts across gender, racial and socio-economic lines, with roughly equal shares of teens across demographic groups saying it is a significant issue in their community.

Fewer teens, though still substantial shares, voice concern over bullying, drug addiction and alcohol consumption. More than four-in-ten say these are major problems affecting people their age in the area where they live, according to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17.

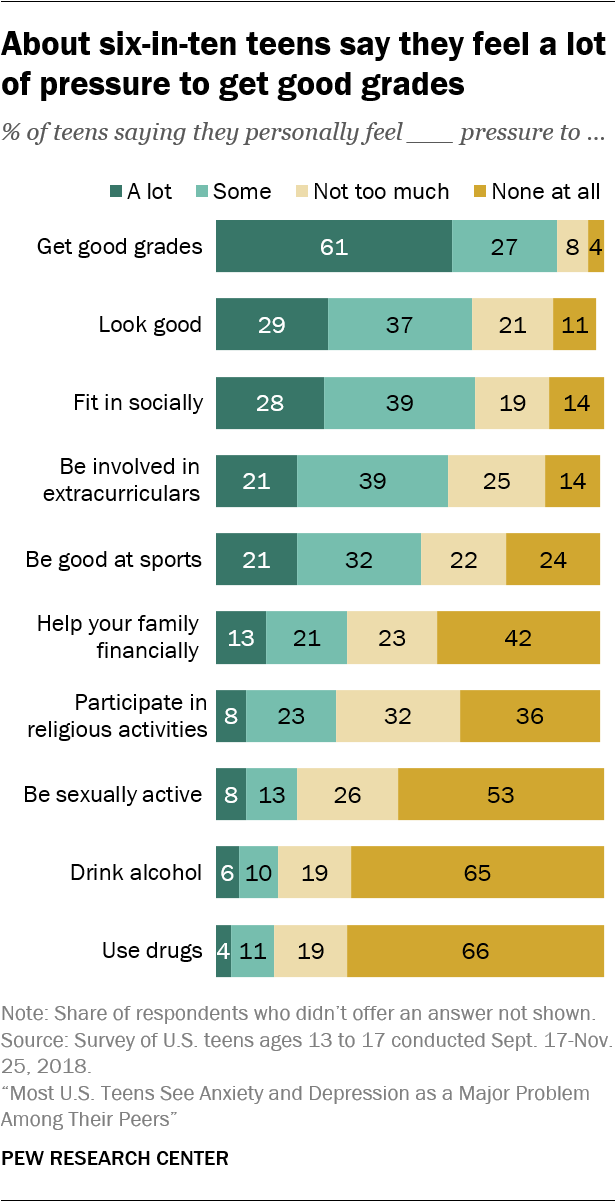

When it comes to the pressures teens face, academics tops the list: 61% of teens say they feel a lot of pressure to get good grades. By comparison, about three-in-ten say they feel a lot of pressure to look good (29%) and to fit in socially (28%), while roughly one-in-five feel similarly pressured to be involved in extracurricular activities and to be good at sports (21% each). And while about half of teens see drug addiction and alcohol consumption as major problems among people their age, fewer than one-in-ten say they personally feel a lot of pressure to use drugs (4%) or to drink alcohol (6%).

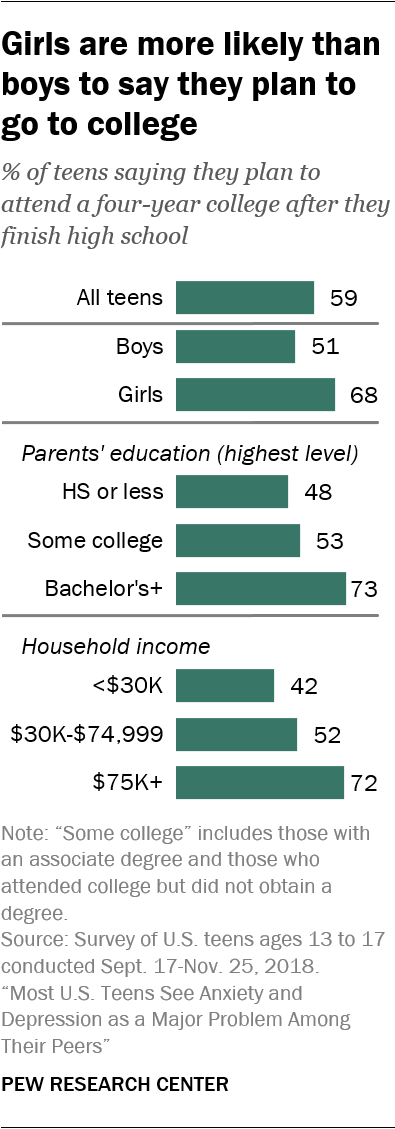

The pressure teens feel to do well in school is tied at least in part to their post-graduation goals. About six-in-ten teens (59%) say they plan to attend a four-year college after they finish high school, and these teens are more likely than those who have other plans to say they face a lot of pressure to get good grades.

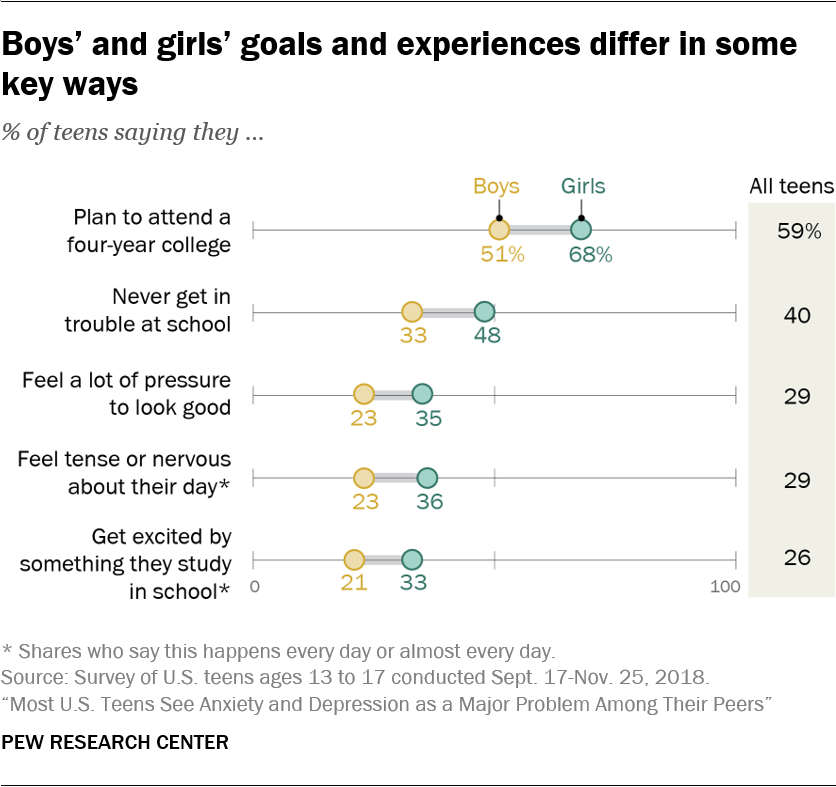

Girls are more likely than boys to say they plan to attend a four-year college (68% vs. 51%, respectively), and they’re also more likely to say they worry a lot about getting into the school of their choice (37% vs. 26%). Current patterns in college enrollment among 18- to 20-year-olds who are no longer in high school reflect these gender dynamics. In 2017, 64% of women in this age group who were no longer in high school were enrolled in college (including two- and four-year colleges), compared with 55% of their male counterparts.

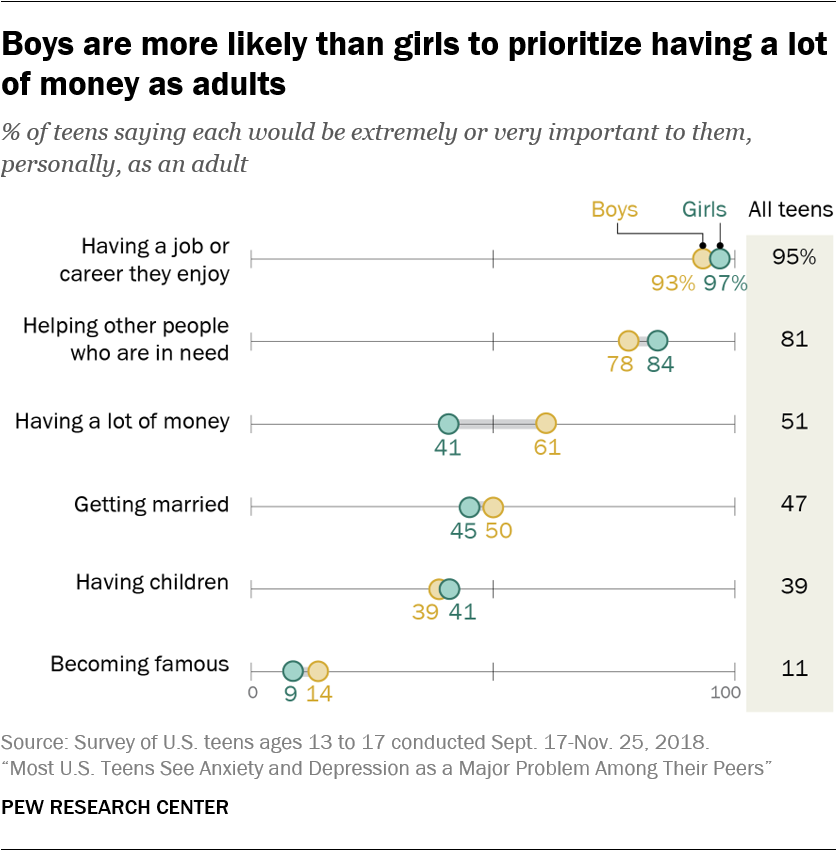

In many ways, however, the long-term goals of boys and girls don’t differ significantly. About nine-in-ten or more in each group say having a job or career they enjoy would be extremely or very important to them as an adult (97% of girls and 93% of boys say this). And similar shares of girls and boys see getting married (45% and 50%, respectively) and having children (41% and 39%) as priorities for them, personally, when they grow up. Still, boys are considerably more likely than girls to say having a lot of money would be extremely or very important to them (61% vs. 41%).

While boys and girls face many of the same pressures – for example, they’re about equally likely to say they feel pressure to get good grades – their daily experiences differ in other ways. Girls are more likely than boys to say they face a lot of pressure to look good: About a third of girls (35%) say this is the case, compared with 23% of boys. And a larger share of girls than boys say they often feel tense or nervous about their day (36% vs. 23%, respectively, say they feel this way every day or almost every day). At the same time, girls are more likely to say they regularly get excited about something they study at school: 33% of girls say this happens every day or almost every day, versus 21% of boys. And while small shares of girls (7%) and boys (5%) say they get in trouble at school daily or almost daily, girls are more likely than boys to say this never happens to them (48% vs. 33%).

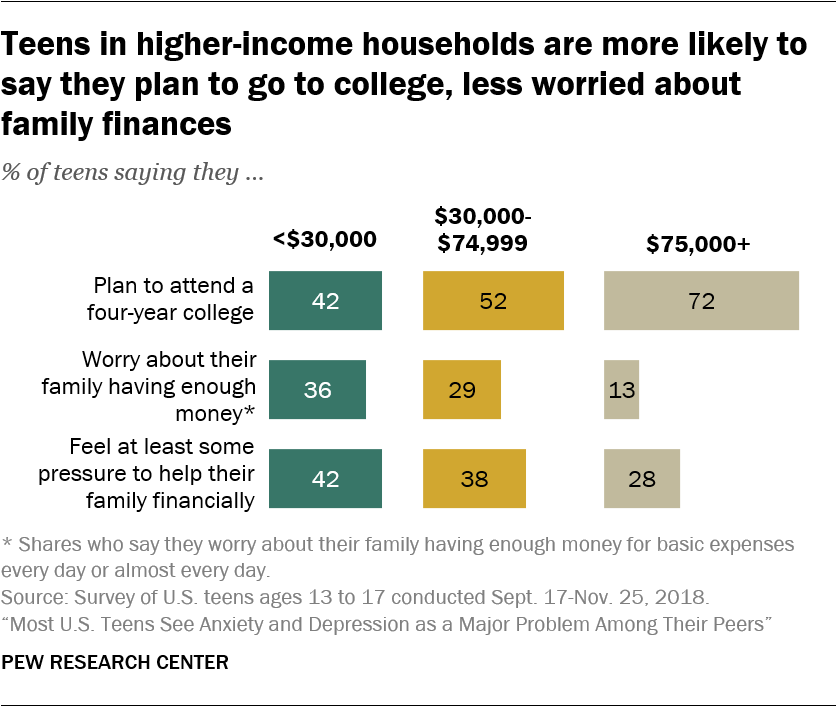

In addition to these gender differences, the survey also finds some differences in the experiences and aspirations of teens across income groups. About seven-in-ten teens in households with annual incomes of $75,000 or more (72%) say they plan to attend a four-year college after they finish high school; 52% of those in households with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 42% in households with incomes below $30,000 say the same. Among teens who plan to attend a four-year college, those in households with incomes below $75,000 express far more concern than those with higher incomes about being able to afford college.

And while a relatively small share of teens overall say they face a lot of pressure to help their family financially, teens in lower-income households are more likely to say they face at least some pressure in this regard.

There are also differences by household income in the problems teens say exist in their communities. Teens in lower-income households are more likely to say teen pregnancy is a major problem among people their age in the area where they live: 55% of teens in households with incomes below $30,000 say this, versus 38% of those in the middle-income group and an even smaller share (22%) of those in households with incomes of $75,000 or more. Compared with teens in the higher-income group, those in households with incomes below $30,000 are also more likely to cite bullying, drug addiction, poverty and gangs as major problems.

A note on racial and ethnic differences among teens

The survey suggests that, in some ways, the attitudes and experiences of teens may vary along racial and ethnic lines. However, because of small sample sizes and a reduction in precision due to weighting, estimates are not presented by racial or ethnic groups.

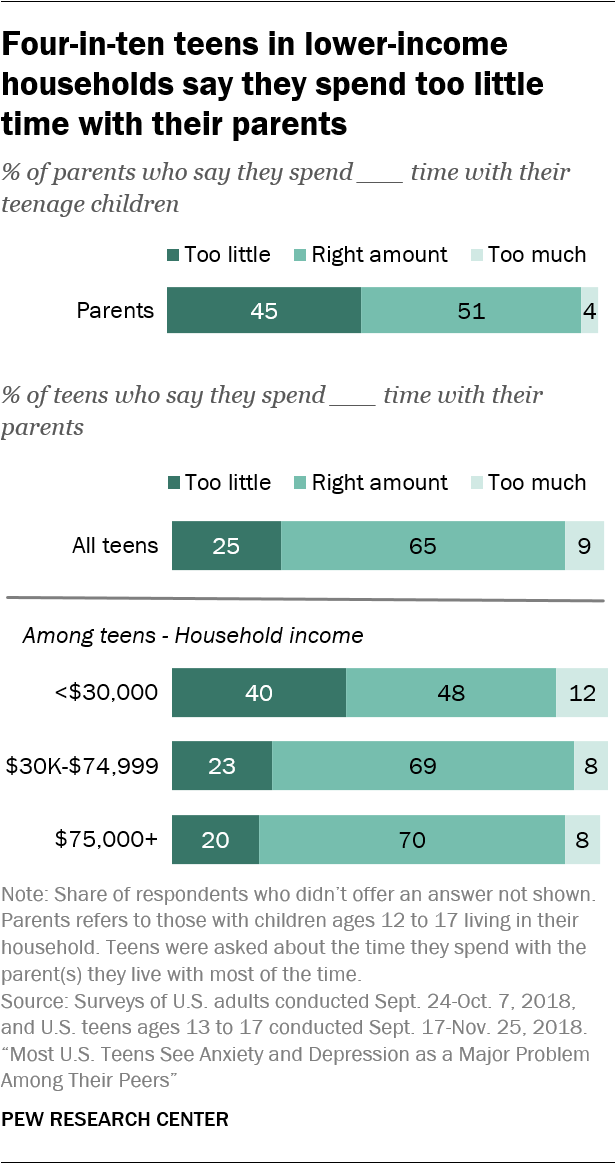

Teens in lower-income households also have different assessments of the amount of time they spend with their parents. Four-in-ten teens in households with incomes below $30,000 say they spend too little time with their parents, compared with about one-in-five teens in households with higher incomes.

These are among the key findings of a survey of 920 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted online Sept. 17-Nov. 25, 2018.1 Throughout the report, “teens” refers to those ages 13 to 17.

A majority of teens say they plan to attend a four-year college after high school

About six-in-ten teens (59%) say they plan to attend a four-year college after they finish high school; 12% plan to attend a two-year college, 5% plan to work full time, 4% plan to enroll in a technical or vocational school and 3% plan to join the military. Another 13% of teens say they are not sure what they’ll do after high school.

Girls are more likely than boys to say they plan to attend a four-year college after finishing high school: 68% of girls say this, compared with about half of boys (51%). Differences in the shares of boys and girls who say they plan to attend a two-year college, enroll in a technical or vocational school, work full time or join the military after high school are small or not significant.

Among teens with at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree or higher, as well as those in households with annual incomes of $75,000 or more, about seven-in-ten say they plan to attend a four-year college after high school. By comparison, about half of teens whose parents don’t have a bachelor’s degree or with household incomes below $75,000 say the same.

Some 65% of teens who say they plan to attend a four-year college after high school say they worry at least some about being able to afford college. Similarly, 70% express at least some concern about getting into the college of their choice.

Perhaps not surprisingly, concerns about affording college are more prevalent among teens in lower-income households. Among teens who say they plan to attend a four-year college, about three-quarters (76%) in households with incomes below $75,00o say they worry at least some about being able to afford it, compared with 55% of those in households with incomes or $75,000 or more.

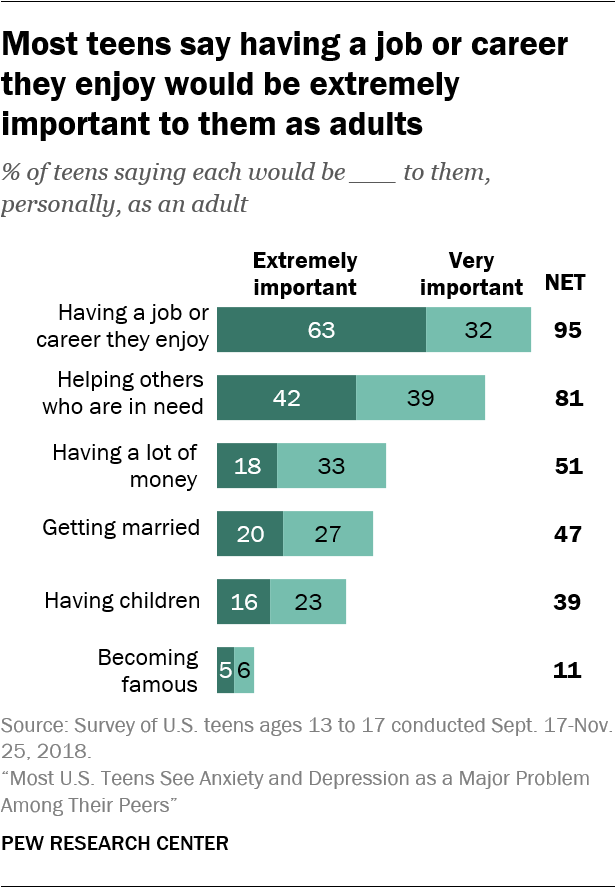

Having a job or career they enjoy is at the top of teens’ long-term goals

Looking ahead, virtually all teens say they aspire to having a job or career they enjoy: 63% say this would be extremely important to them, personally, as adults, and another 32% say it would be very important. Most teens also say helping other people who are in need would be extremely (42%) or very (39%) important to them when they grow up.

Teens give lower priority to marriage and kids. About half (47%) say getting married would be extremely or very important to them as adults, and 39% say the same about having children.

When it comes to fortune and fame, 51% of teens say having a lot of money would be extremely or very important to them, while relatively few (11%) say the same about becoming famous.

For the most part, boys and girls have similar aspirations. Roughly equal shares of boys and girls say getting married, having kids, and having a job or career they enjoy would be extremely or very important to them as adults. But boys (61%) are far more likely than girls (41%) to say having a lot of money when they grow up would be extremely or very important to them.

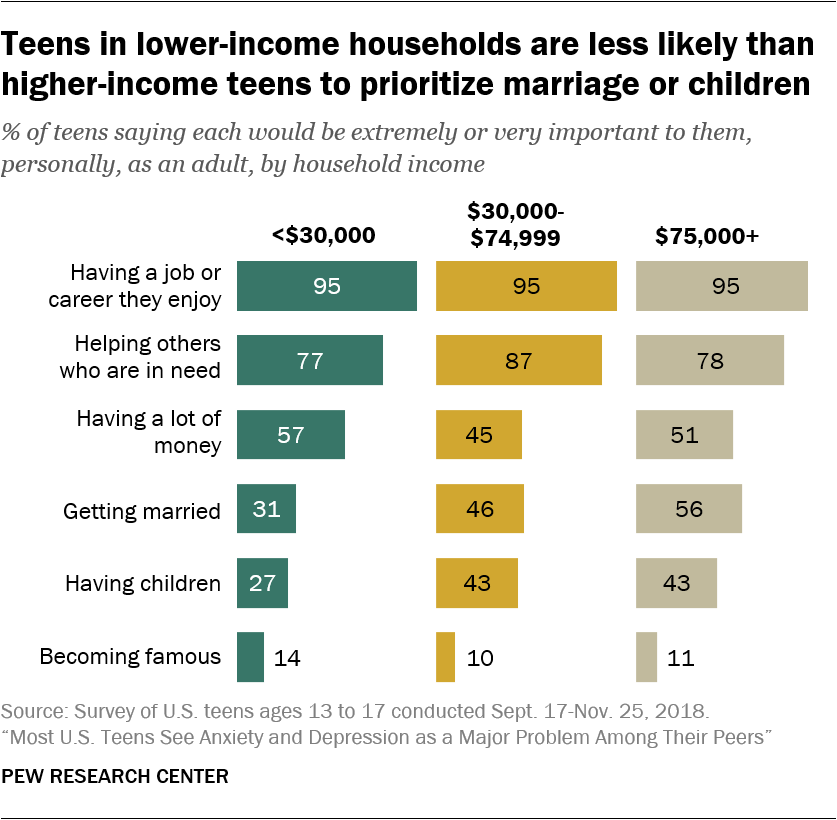

Teens’ aspirations are also fairly consistent across income levels, with similar shares in each income group saying having a job or career they enjoy, helping others in need, having a lot of money and becoming famous would be extremely or very important to them as adults.

However, teens in households with incomes below $30,000 are less likely than those in households with higher incomes to prioritize marriage and children. Some 56% of teens in households with incomes of $75,000 or more and 46% in households with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 say getting married would be extremely or very important to them when they grow up, compared with 31% of those in the lower-income group. And while about four-in-ten in the higher- and middle-income groups (43% each) say having children would be extremely or very important to them, 27% of those in the lower-income group say the same.

Academics are at forefront of the pressures teen face

Most teens (61%) say they personally feel a lot of pressure to get good grades, and another 27% say they feel some pressure to do so.

Compared with getting good grades, about half as many say they feel a lot of pressure to look good (29%) and to fit in socially (28%). Roughly one-in-five say they face a lot of pressure to be involved in extracurricular activities and to be good at sports (21% each), while smaller shares say they feel a lot of pressure to help their family financially (13%), to participate in religious activities (8%), to be sexually active (8%), to drink alcohol (6%) or to use drugs (4%).

Boys and girls, as well as teens across income groups, generally feel similar levels of pressure in each of these realms, but there are some exceptions. Girls are more likely than boys to say they feel a lot of pressure to look good (35% vs. 23%). And teens in the lower- and middle-income groups are more likely than those in higher-income households to say they feel at least some pressure to help their family financially (42% and 38%, respectively, vs. 28%).

In some ways, teens’ day-to-day experiences vary by gender and income

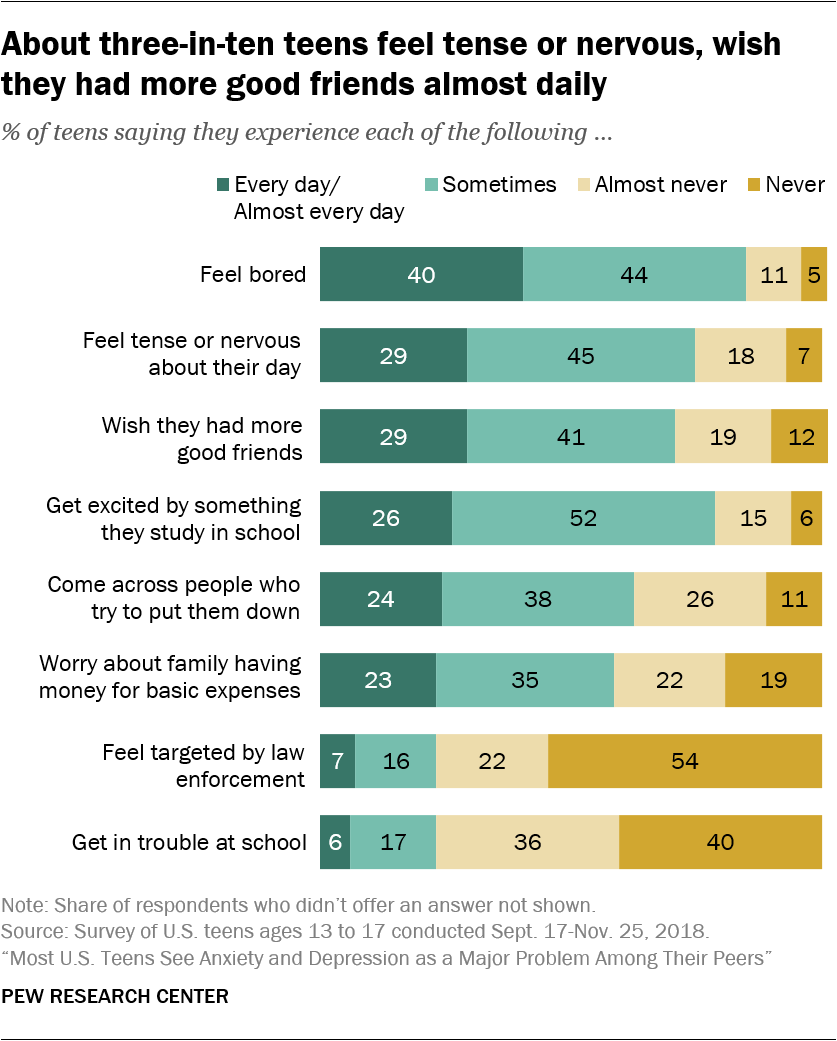

When asked how often they have certain experiences or feelings, four-in-ten teens say they feel bored every day or almost every day, while about three-in-ten say they feel tense or nervous about their day (29%) or wish they had more good friends (29%) with the same frequency. Roughly a quarter of teens say they get excited by something they study in school (26%), come across people who try to put them down (24%) or worry about their family having enough money for basic expenses (23%) every or almost every day.

Smaller shares say they regularly feel targeted by law enforcement (7%) or get in trouble at school (6%). In fact, 54% of teens say they never feel targeted by law enforcement, and 40% say they never get in trouble at school.

Concerns about their family having enough money for basic expenses differ greatly by income: 36% of teens in the lower-income group and 29% of those in the middle-income group say they worry about this daily or almost daily, whereas 13% of teens in higher-income households say the same.

Gender differences are also apparent, particularly when it comes to experiences in school. Girls are more likely than boys to say they get excited every or almost every day by something they study in school (33% vs. 21%), and they’re less likely to get in trouble at school. About half of girls (48%) say they never get in trouble at school, compared with 33% of boys. In addition, higher shares of girls than boys say they feel tense or nervous about their day on a daily or almost daily basis (36% vs. 23%).

Parents are more likely to say they don’t spend enough time with their teens than teens are to say the same about their parents

When it comes to the amount of time they spend with each other, parents and teens diverge in their assessments, with parents far more likely to say it’s not enough. Among parents who live with their teens, 45% say they spend too little time with their teenage children; a quarter of teens say the same about the time they spend with their parents.2 Most teens (65%) say they spend the right amount of time with their parents, while 9% say they spend too much time.

Teens from lower-income households are the most likely to say they spend too little time with their parents: Four-in-ten teens in households with annual incomes below $30,000 say this, compared with roughly one-in-five in households with higher incomes. These same income differences are not evident among parents, however. Similar shares of parents across income levels say they spend too little time with their teenage children.

Among parents who live with their teens, fathers are more likely than mothers to say they spend too little time with their teenage children (53% vs. 39%).

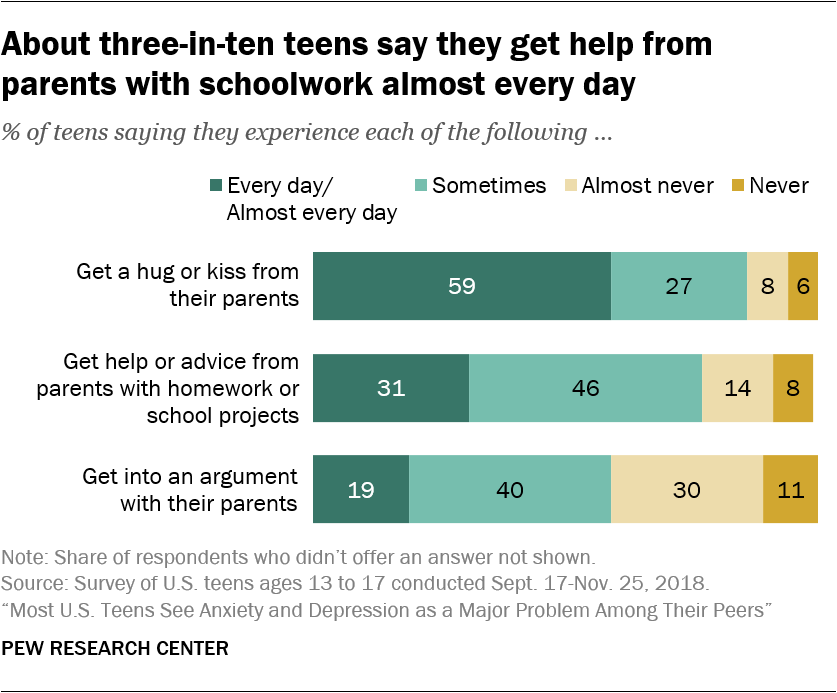

Majority of teens say they get a hug or kiss from their parents almost daily

When asked about interactions with their parents, about six-in-ten teens (59%) say they get a hug or kiss from their parents every day or almost every day. Roughly three-in-ten (31%) say they get help or advice from their parents with homework or school projects on a daily or almost daily basis, and 19% say they regularly get into arguments with their parents.

Girls and boys are about equally likely to say they get a hug or kiss from their parents every day or almost every day, as are teens from different socio-economic backgrounds.

The share of teens who say their parents help them with homework or school projects every day or almost every day is considerably lower than it was two decades ago. A Public Agenda survey conducted in 1996 found that, at that time, about half of teens (48%) reported daily or almost daily involvement from parents in their schoolwork.3