On key economic outcomes, single adults at prime working age increasingly lag behind those who are married or cohabiting

This analysis uses decennial census and American Community Survey data to examine the single, 25- to 54-year-old U.S. population and compare it with adults who are either married or living with an unmarried partner. Though the decennial census has collected information on marital status for many decades, it was not until the 1990 census that unmarried partners of the household head were distinguished from roommates and housemates. The breadth and detail of census data facilitates an examination of not only how the unpartnered population at prime working age has grown since 1990, but also its changing characteristics in terms of educational attainment, labor market success and living arrangements.

“Unpartnered” refers to adults who are neither married nor living with an unmarried partner. “Single” is used interchangeably with unpartnered in this report.

References to prime-working-age adults refer to those ages 25 to 54.

References to White, Black and Asian adults include only those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

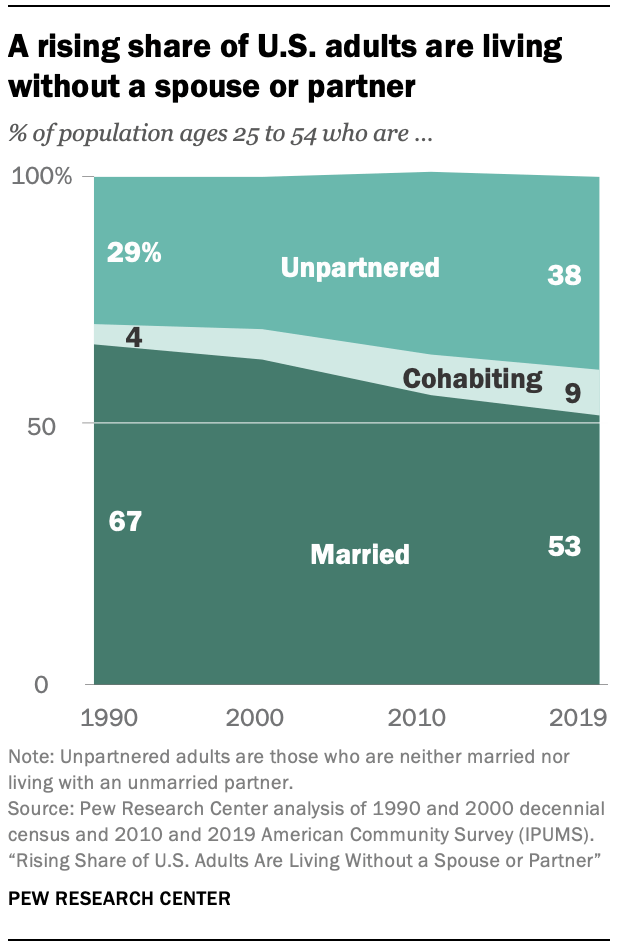

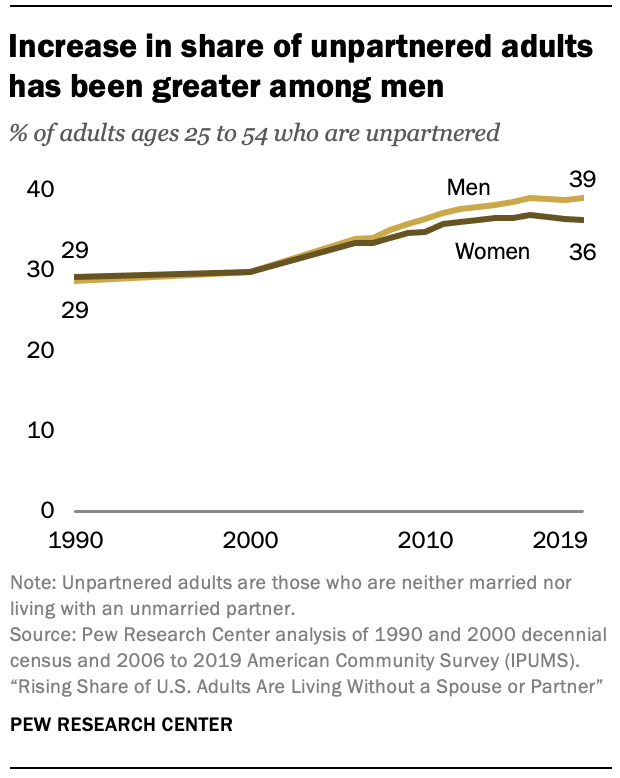

As relationships, living arrangements and family life continue to evolve for American adults, a rising share are not living with a romantic partner. A new Pew Research Center analysis of census data finds that in 2019, roughly four-in-ten adults ages 25 to 54 (38%) were unpartnered – that is, neither married nor living with a partner.1 This share is up sharply from 29% in 1990.2 Men are now more likely than women to be unpartnered, which wasn’t the case 30 years ago.

The growth in the single population is driven mainly by the decline in marriage among adults who are at prime working age. At the same time, there has been a rise in the share who are cohabiting, but it hasn’t been enough to offset the drop in marriage – hence the overall decline in partnership. While the unpartnered population includes some adults who were previously married (those who are separated, divorced or widowed), all of the growth in the unpartnered population since 1990 has come from a rise in the number who have never been married.

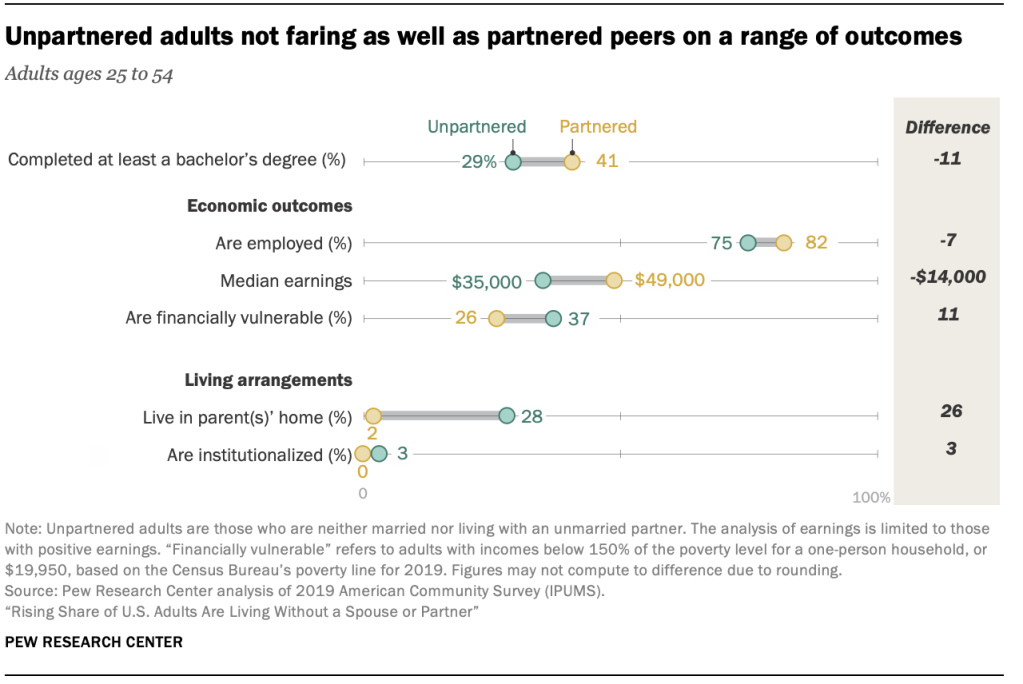

This trend has broad societal implications, as does the growing gap in well-being between partnered and unpartnered adults. Looking across a range of measures of economic and social status, unpartnered adults generally have different – often worse – outcomes than those who are married or cohabiting. This pattern is apparent among both men and women. Unpartnered adults have lower earnings, on average, than partnered adults and are less likely to be employed or economically independent. They also have lower educational attainment and are more likely to live with their parents. Other research suggests that married and cohabiting adults fare better than those who are unpartnered when it comes to some health outcomes.

The gaps in economic outcomes between unpartnered and partnered adults have widened since 1990. Among men, the gaps are widening because unpartnered men are faring worse than they were in 1990. Among women, however, these gaps have gotten wider because partnered women are faring substantially better than in 1990.

The growing gap in economic success between partnered and unpartnered adults may have consequences for single men who would like to eventually find a partner. In a 2017 Pew Research Center survey, 71% of U.S. adults said being able to support a family financially is very important for a man to be a good spouse or partner. Similar shares of men and women said this. In contrast, 32% of adults – and just 25% of men – said this is very important for a woman to be a good spouse or partner.

A growing share of adults are unpartnered

Americans’ marital and living arrangements have changed considerably over the past 30 years. The share of adults ages 25 to 54 who are currently married fell from 67% in 1990 to 53% in 2019, while the share cohabiting more than doubled over that same period (from 4% in 1990 to 9% in 2019).3 The share who have never been married has also grown – from 17% to 33%. All of this churn has resulted in a significant increase in the share who are unpartnered.

The growth in unpartnered adults has been sharper among men than women. In 1990, men and women ages 25 to 54 were equally likely to be unpartnered (29% of each group). By 2019, 39% of men were unpartnered, compared with 36% of women.

In terms of their demographic characteristics, prime-working-age single adults are somewhat younger than their counterparts who are married or living with a partner. Among adults ages 25 to 54, the median age of those who are unpartnered was 36 in 2019; this compares with 40 among partnered adults.

Some may assume that, as the median age of first marriage continues to rise, unpartnered adults are merely lagging behind rather than foregoing partnership altogether. That might not be the case. Among adults ages 40 to 54, there has been a significant increase in the share who are unpartnered from 1990 (24%) to now (31% in 2019).

There are differences by race and ethnicity in the share of prime-working-age adults who are partnered and unpartnered. Among those ages 25 to 54, 59% of Black adults were unpartnered in 2019. This is higher than the shares among Hispanic (38%), White (33%) and Asian (29%) adults. For most racial and ethnic groups, men are more likely than women to be unpartnered. The exception is among Black adults, where women (62%) are more likely to be unpartnered than men (55%).

Partnership status also differs by nativity. Foreign-born adults at prime working age were less likely (28%) to be unpartnered in 2019 than their native-born peers (40%). This pattern is apparent among adults of each major racial or ethnic origin. For example, 29% of foreign-born Hispanic adults were single, compared with 46% of native-born Hispanic adults. Some of this difference in partnership status may reflect that foreign-born prime-working-age adults are older than their native-born counterparts.

On average, unpartnered adults have worse economic outcomes than partnered adults

On a variety of outcomes, be it education, employment or living arrangements, unpartnered adults fare differently than partnered adults. Because the size of the gap associated with partnership differs between men and women, results are presented separately for both genders.

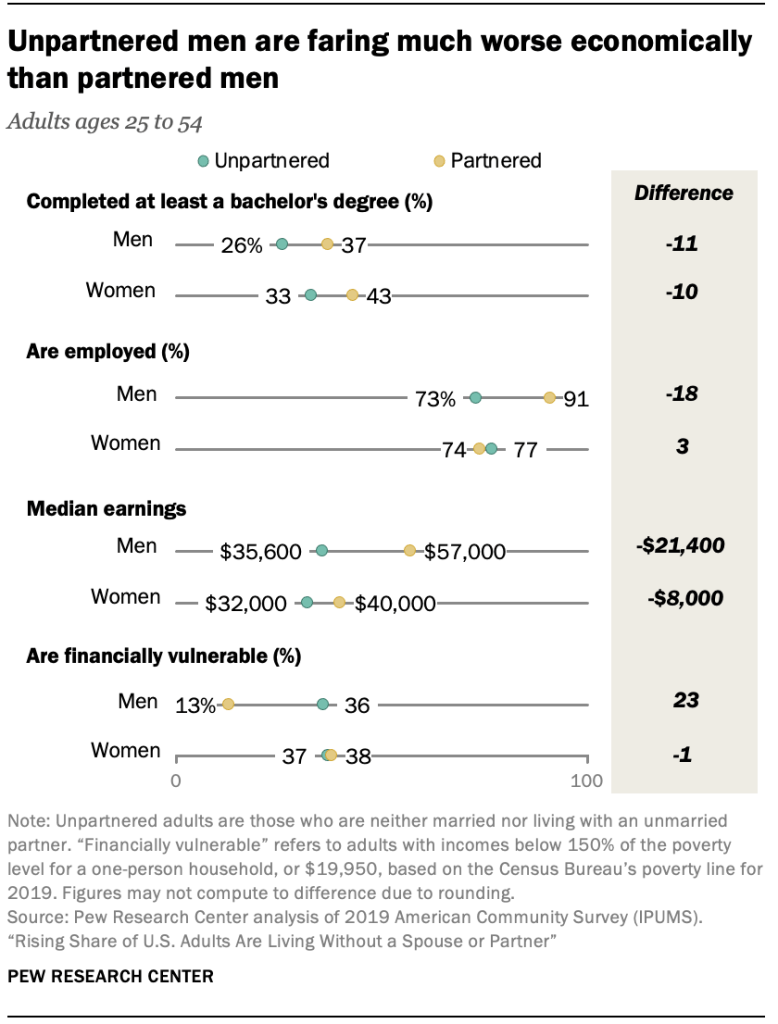

When it comes to educational attainment, 26% of unpartnered prime-working-age men had completed at least a bachelor’s degree in 2019. This markedly trails the 37% of partnered men who had finished college. Similarly, 33% of unpartnered women in 2019 had finished at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 43% of partnered women.

Outcomes differ for married, cohabitating and unpartnered adults

This analysis is based on the premise that adults who live with a romantic partner – whether they are married or cohabitating – have significantly different (often better) economic outcomes than those who are not living with a romantic partner. But it’s important to note that outcomes also differ between married and cohabiting adults.

Cohabiting adults tend to fare better than unpartnered adults, and married adults fare better still. On many dimensions, cohabiting adults are more similar to married adults than to single adults. There are exceptions as well as differences by gender. For example, among women, those in cohabiting relationships (80%) are more likely to be employed than unpartnered (77%) or married (73%) women. Among men, while those who cohabit (89%) are less likely to be employed than those who are married (92%), they’re much more likely than single men to have a job (73%).

Since a relatively small share of adults ages 25 to 54 are cohabiting (9%), combining them with married adults to paint a fuller picture of those who are living with a romantic partner does not markedly change the size or the direction of the gaps that exist between partnered and unpartnered adults. (See Appendix A for a detailed breakdown.)

The economic outcomes of prime-working-age men differ substantially by partnership status. In 2019, 73% of men without a partner were employed, compared with 91% of partnered men. The gap in employment among women, which is more modest, goes in the opposite direction: 77% of single women held a job in 2019, compared with 74% of women with a partner.

In 2019, the median earnings of men without a partner were $35,600, lagging far behind those of partnered men ($57,000).4 Unpartnered women also trail their partnered counterparts in median earnings ($32,000 and $40,000, respectively), but the gap is not as large.

Another measure of economic standing compares an individual’s income with a threshold of the resources needed to live independently.5 In this analysis, an income of 150% of the official poverty level for a one-person household ($19,950 based on a poverty cutoff of $13,300 in 2019) is used as a benchmark for living independently. Adults whose total income is below this threshold are considered “financially vulnerable.”

In 2019, 36% of unpartnered men would have been considered financially vulnerable based on their individual income. This is nearly three times the share of partnered men with vulnerable incomes (13%). In contrast, there was little difference in the share of unpartnered and partnered women who were financially vulnerable (37% and 38%, respectively). The parity among women partly reflects the differing child care responsibilities of partnered versus unpartnered women. As reported below, partnered women are about twice as likely as their unpartnered counterparts to live with one or more of their own children, and mothers are generally less likely to work full-time and full-year.

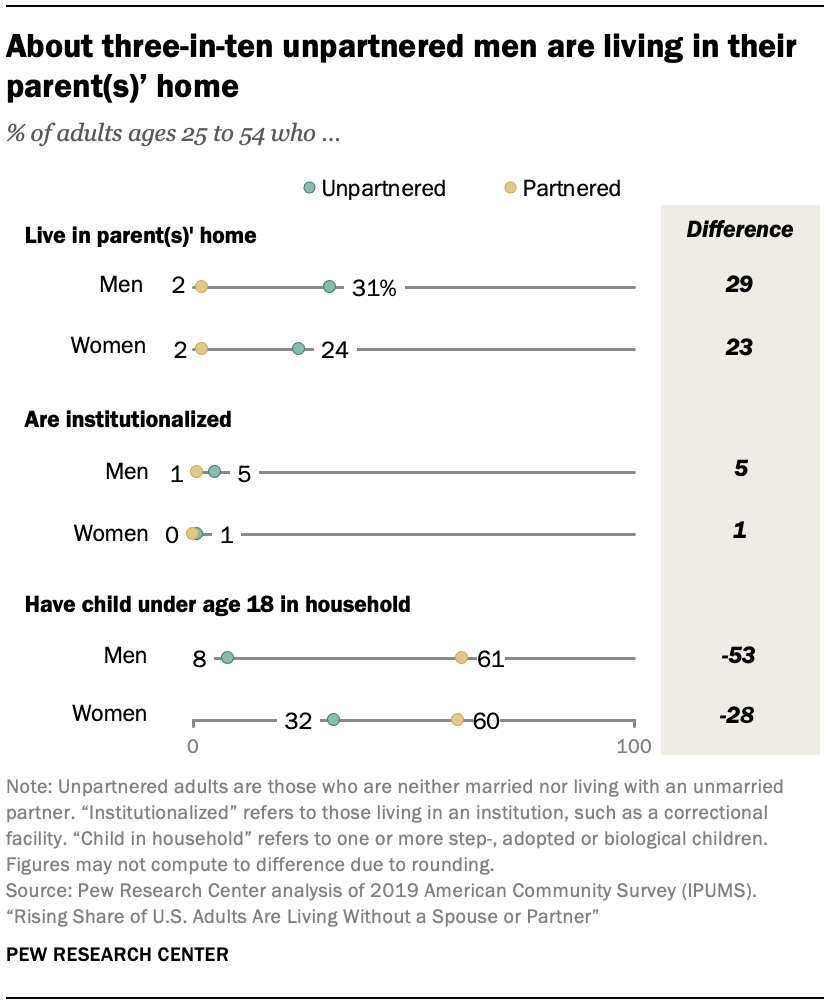

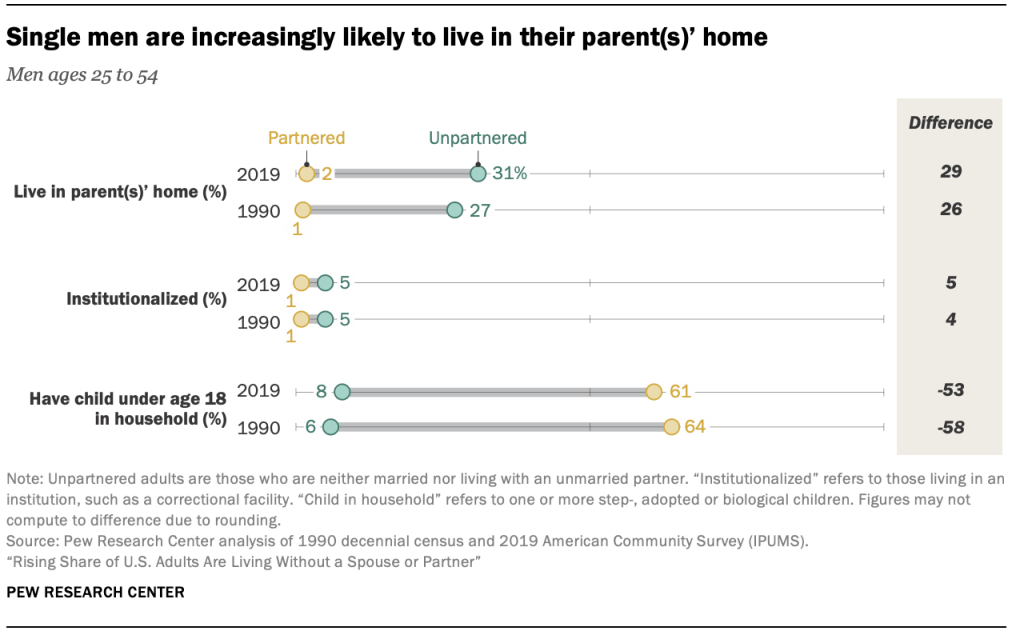

There are stark differences in the living arrangements of partnered and unpartnered prime-working-age adults, particularly among men. Roughly three-in-ten unpartnered men (31%) lived in the home of at least one of their parents in 2019. Among men who were married or cohabiting, only 2% of them resided in the home of their parent(s). Some of the gap reflects that unpartnered men tend to be younger than partnered men. However, even when looking only at unpartnered men ages 40 to 54, a sizable share (20%) lived in their parent(s)’ home.

About a quarter (24%) of unpartnered women lived with at least one parent in 2019 (compared with only 2% of partnered women).

As of 2019, 5% of unpartnered men resided in institutionalized group quarters. (For adults of prime working age, this largely refers to adult correctional facilities.) This compares with 1% of partnered men. The share of women who were living in an institutional setting (whether they are partnered or not) was extremely low – 1% for unpartnered and fewer than 1% for partnered women.

Not surprisingly, unpartnered adults are much less likely than partnered adults to have a child of their own in their household. Among men, 8% of the unpartnered lived with a child of their own in 2019. (This includes stepchildren and adopted children as well as biological children.) Among partnered men, 61% were living with at least one child. The gap is smaller among women: Roughly a third of unpartnered women (32%) lived with at least one child, compared with 60% of partnered women.

Researchers have considered why this relationship between partnership status and economic outcomes exists, particularly for men. Is it driven by the fact that men with higher levels of education, higher wages and better prospects for the future are more desirable potential spouses? Or is there something about marriage or partnership that gives a boost to a man’s economic outcomes? The research suggests that both factors are at play. Married men earn more because high earners are more likely to marry in the first place. Cohabiting men also receive a wage premium. In addition, marriage or partnership may make men more productive at work, thus adding to the wage premium that already exists.

Less attention has focused on the benefits of partnership for women, but marriage and cohabitation are associated with wage gains for childless women. The effects may be more modest for women, but marriage benefits men’s and women’s wages through similar processes.

Since 1990, worse outcomes for unpartnered men and better outcomes for partnered women

The economic gap between single and partnered adults has generally grown wider since 1990, though exceptions exist. The change has been greater on some measures among women than men, and the dynamics underlying the shifts reflect different realities for each group. For women the gaps have widened not because unpartnered women are faring worse now than 1990, but rather because partnered women have experienced significant improvements in their outcomes. In contrast, the economic gap between unpartnered and partnered men has widened mainly because the former are faring worse on most indicators.

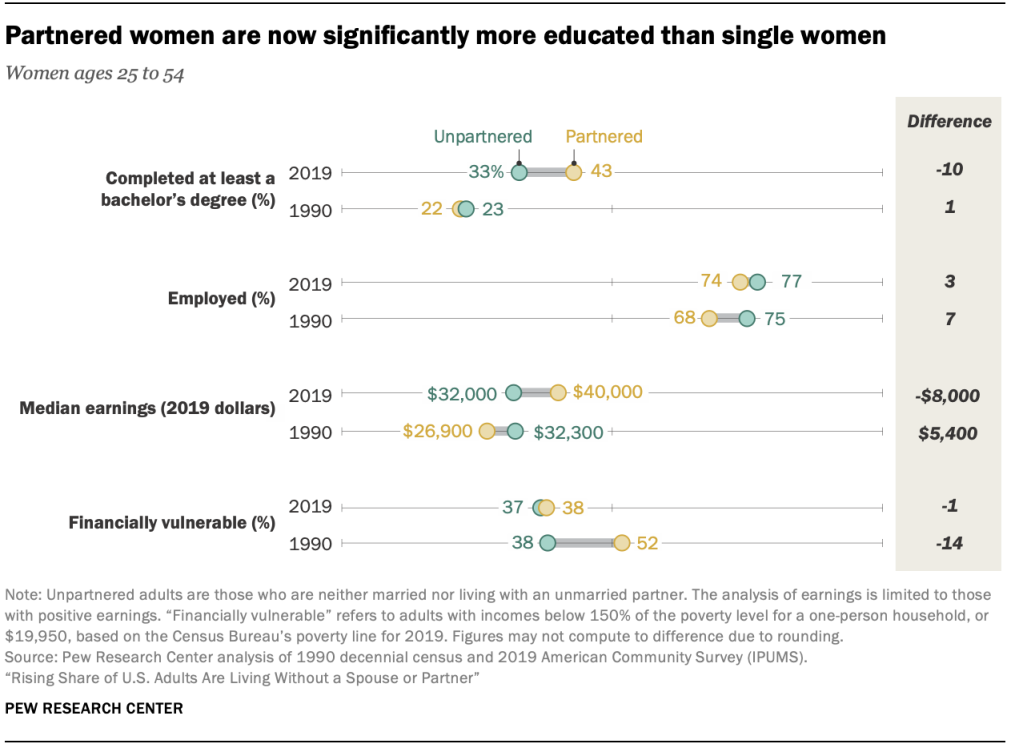

In 1990, similar shares of unpartnered (23%) and partnered (22%) women had completed at least a bachelor’s degree. Both groups have improved their educational attainment, but partnered women have made greater strides. By 2019, 43% of partnered women were college graduates, resulting in a significant gap in educational attainment between the two groups.

Partnered women have closed some of the gap in employment with single women. In 1990, single women were significantly more likely to be working than partnered women. Employment has increased among both groups, but especially among partnered women – a 7 percentage point gap has narrowed to 3 points. This is due in large part to the growing share of mothers who have entered the labor force since 1990.

In 1990, unpartnered women at the median out-earned their partnered counterparts ($32,300 vs. $26,900). Unpartnered women’s median earnings have since remained stagnant, while partnered women’s median earnings have increased by $13,100. A $5,400 gap in favor of single women has reversed and as of 2019 had become an $8,000 earnings gap in favor of partnered women.

Relatedly, the income received by partnered women has increased substantially since 1990, and far fewer of them lack the resources to live independently. The share of single women who are financially vulnerable has not changed much (from 38% in 1990 to 37% in 2019).

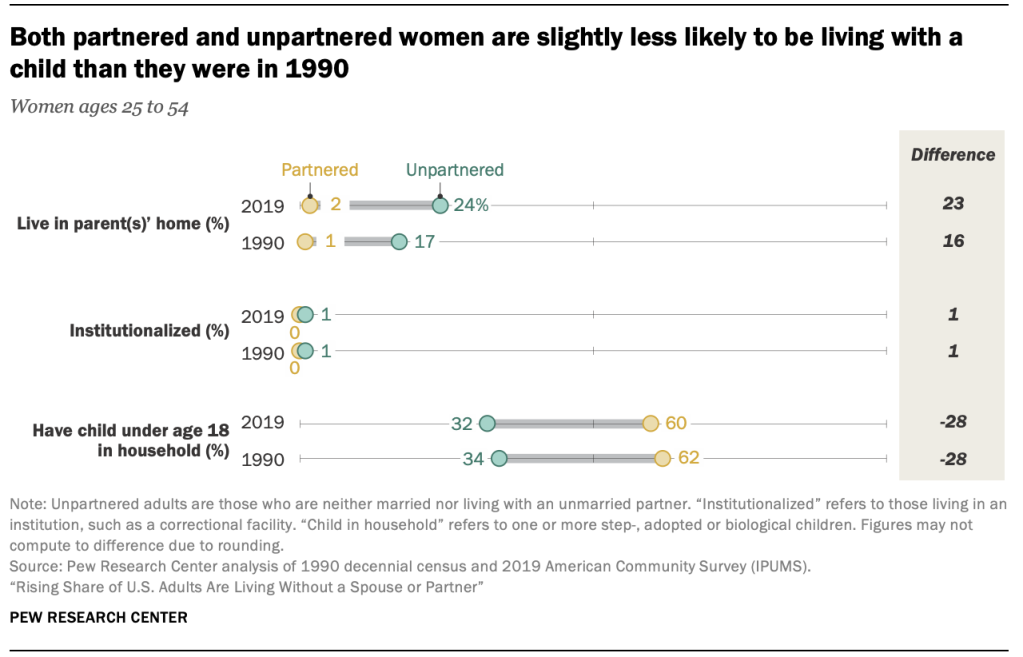

When it comes to living arrangements, compared with 1990, a significantly higher share of single women now reside with at least one parent, so the gap on this score between single and partnered women has widened (from 16 to 23 percentage points by 2019).

Differences in the shares of single and partnered women who are living with a child have not changed substantially. Both groups were slightly less likely to have a child in their household in 2019 than in 1990.

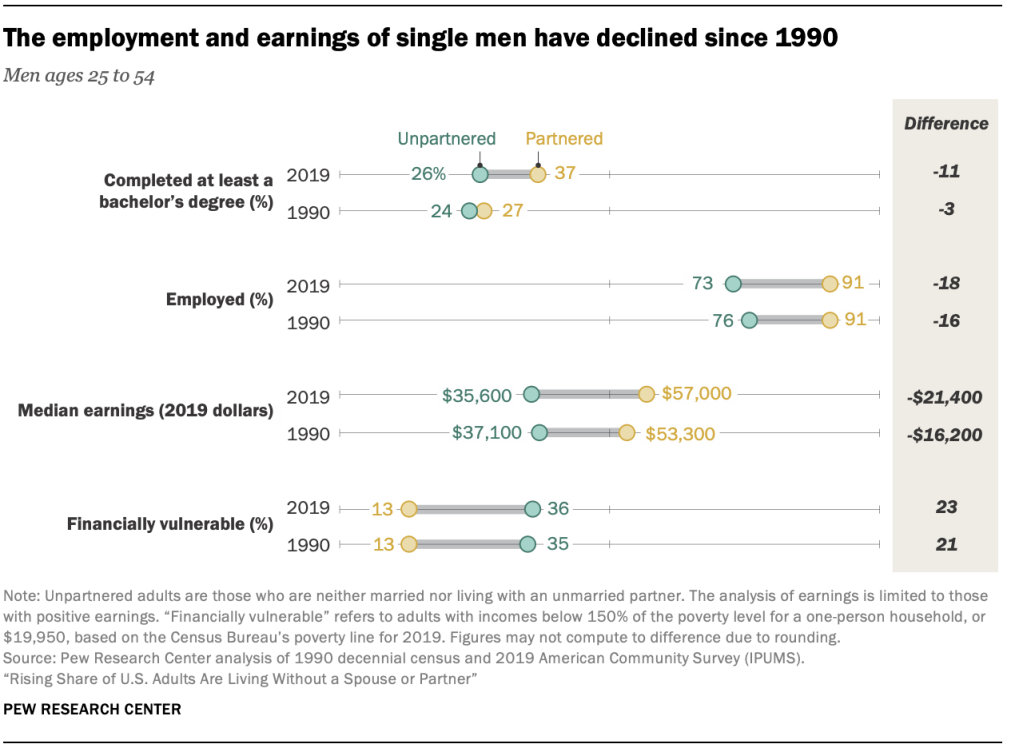

Turning to men, single men have made only minimal gains in educational attainment since 1990. By 2019, 26% of single men had completed at least a bachelor’s degree, up from 24% in 1990. Educational gains have been much more substantial for partnered men over this period. The share who had completed at least a bachelor’s degree rose 11 percentage points from 1990 to 2019, increasing the educational gap between partnered and unpartnered men from 3 to 11 percentage points.

Single men have fallen further behind their partnered counterparts educationally at a time when job opportunities for less-educated men in the U.S. labor market have become more limited. This is reflected in trends in employment and earnings. Many studies have documented rising joblessness among less-educated men of prime working age accompanied by falling real wages since 1980. There is less consensus on the factors contributing to these declining fortunes, but explanations usually include those involving both the demand for less-educated workers and the supply.

Unpartnered men were less likely to be employed in 2019 (73%) than they were in 1990 (76%).6 Consequently, a 16 percentage point gap in job holding between single and partnered men has widened somewhat to 18 points. The gap in earnings has widened even more. Single men are the only one of the four demographic groups to have experienced a significant decline in their inflation-adjusted median earnings. The typical earnings of unpartnered men have fallen by $1,500 since 1990. Combined with the earnings gains among partnered men, the earnings gap between single and partnered men widened from $16,200 in 1990 to $21,400 in 2019.

As is the case among women, unpartnered men are more likely now to be living with a parent than they were in 1990, while the share of partnered men doing so has remained about the same. Some 31% of single men lived with a parent in 2019, up from 27% in 1990. The gap in the share of men who are institutionalized has widened over this period.

When it comes to living with children, 8% of unpartnered men did so in 2019, compared with 61% of partnered men. The gap between the two groups of men has narrowed somewhat over the past 30 years but remains quite large.